February 4, 2022

Dear Interested Readers,

Maintaining Perspective While Living with Uncertainty

Most Monday mornings at 9 AM I click on a Zoom link and join a conversation with five of my friends. We are all “mostly retired.” One participant is a former screenwriter, with significant Hollywood credits who is now serving as a middle school substitute teacher and has a very popular after-school writing project with middle schoolers. He also teaches an evening course in English for people hoping to pass the GED test. He occasionally misses our meetings because he is teaching. The rest of us find activity in a variety of non-profit volunteer service activities.

One member of the group is a lawyer who once was the chief operating officer of a large electric company and still does a little consulting from time to time. Another member was a mental health professional who had a statewide managerial responsibility in a neighboring state. There is one “townie” in our group. He was a civil engineer and is a very good guitar player. The last member of the group, our youngest member, had been an actress, a wife, and a single mother before she became a minister. She retired recently and now devotes time to secular non-profit activities and continues to meet with the many people who come to her for advice and comfort at difficult moments in their lives. All of us share deep concerns about the future of our country. We also share the sad concern that so many Christians have a sense of compatibility with Donald Trump and his message that we now feel alienated from many friends and family members.

Currently, we are revisiting a book that we studied before the pandemic, The Christ of the Mount: a working philosophy of life. It is a thorough review and explanation of the “Sermon on the Mount.” It is an old book that was first published in 1931. The author, E. Stanley Jones, was a Methodist missionary to India who was a close observer of Gandhi and a frequent critic of British colonial rule.

If you have any experience with the famous sermon which is presented in chapters 5,6, and 7 of Matthew’s gospel, you may imagine that it is a checklist for getting into heaven, but Jones presents the sermon as a radical set of instructions for how to live a meaningful and satisfying life on earth. Ironically, Jones is quite ecumenical and observes a substantial overlap between the ideas in the sermon and Gandhi’s non-violent resistance to the British.

It occurred to me that since Martin Luther King, Jr earned his doctorate at Boston University School of Theology which is the oldest seminary in America that is affiliated with the United Methodist Church, he was probably aware of the work of Jones. A brief Internet search confirmed my suspicion. In an article from Asbury University where Dr. Jones had been a student in the early 1900s, we read that his influence went far beyond his impact on a young Matin Luther King, Jr.

His reputation as a “reconciler” invited him to many political negotiations in India, Africa, and Asia. He was a close confidant of U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the time preceding World War II, and after the war he was greeted in Japan as the “Apostle of Peace”. He played an important role in establishing religious freedom in the post-colonial Indian government. He became a close friend of Mahatma Gandhi and even wrote a biography of Gandhi, a book which Martin Luther King said influenced him to adopt strict non-violent methods in the American civil rights movement. Jones had a strong influence in preventing the spread of communism in India.

I found one review on goodreads.com that suggested that the book is one that is even better when re-read, and I agree. Rereading and rediscussing Dr. Jones’ words have stimulated some very important insights for me. Jones places emphasis on how to deal with a hostile world and how to treat people with whom you have substantial differences. Appreciating the advice offered in the sermon does not require identifying as a Christian, although Dr. Jones takes every opportunity to advocate for that choice.

In the past, I have told the story of my experience with Dr. Paul Batalden who at the time was a professor at Dartmouth Medical School and one of the most respected voices in our quality movement. He approached the problems in the cost, quality, access, safety, and equity of healthcare as systems failures that could only be resolved with a systems approach. His own ideas were focused on improving the performance of the building blocks of healthcare with what he called a “microsystems” approach. He was one of the founders of the IHI. At the time I last visited the IHI headquarters to meet with Don Berwick, a quote from Batalden was painted on the wall in large letters:

“Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.”

The point of the quote is that even failing systems have been “designed” to get the failing results they get and that if you want better results a more effective design should be your objective. It is a vote for continuous improvement. That is a message that our collective experience with COVID has boldly underlined. In our pursuit of scientific excellence, our dependence on private practice and private industry, in our haphazard design of uniform benefits, and our failure to create a system of care that cares equally about everyone, we have designed a system that was structured to be a disaster when faced with the challenge of a pandemic. The question that faces us now and that I can’t answer is whether we have the will and the consensus that is necessary to effectively address the many problems of design in healthcare today. I fear that without some miracle of bipartisan consensus we have more failure ahead.

I have mentioned Dr. Batalden many times in these notes. You can verify that fact by using the search function on this post. On that day I met Dr. Batalden I was full of enthusiasm for the opportunity to lead my organization toward the objectives of the Triple Aim that were afforded me by my recent appointment as CEO of Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates and Atrius Health. We were active in a program being funded by Blue Cross called “LEAD” which was a demonstration project for quality improvement using systems thinking. Blue Cross had given several Massachusetts hospitals and us a substantial seven-figure grant to do pilot projects in the redesign of care delivery. One of the requirements to get the money was for the CEOs of the participating organizations to meet monthly to study continuous improvement strategies together and to report our individual successes and failures.

Each session had a special focus and a visiting expert, or we visited an organization where we could explore the processes of care improvement. The CEOs had come to Hanover to meet with the experts at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice. As chance would have it, I was assigned to sit next to Dr. Betalden. As the day went along my “clinical sense” kept suggesting to me that I was sitting next to a depressed man. Late in the afternoon as the day was coming to a close, I took advantage of a short break in the presentations to ask Dr. Batalden if he was OK. He was not. He said that he was very concerned that gains of the quality movement over the last couple of decades would be soon lost because the next generation of clinicians was self-interested. He was not convinced that there would be an efficient transfer of the work that had been done to understand quality and promote the insights of Crossing the Quality Chasm or of the Triple Aim to the next generation of providers. He was concerned that they would be more focused on personal success than on the objectives that would be most beneficial to the whole community. I falsely assured him that the very meeting we were attending was evidence that the work would continue.

Well, now I am no longer so sure that Dr. Batalden was wrong. These days I wonder if perhaps Dr. Betalden was clairvoyant. I find myself concerned with the same thoughts he was expressing that day many years ago as I look around at the deficiencies that COVID has uncovered. It appears that my prediction that workforce issues would become a greater challenge than cost issues, and indeed become a cost issue, has come to be a reality. Our system of care is definitely populated by many heroes, but often their efforts are negated or made more difficult by supply issues and systems issues that could have been anticipated and managed years before COVID hit us. Our lack of access and equity in care delivery has cost tens of thousands of disadvantaged or minority group Americans their lives. We see many individuals and companies that have enormous profits from our collective failures. We have “systems” problems that arise out of always focusing on the profitability of the moment more than the durability and long-term performance of critical systems. Sure, the conversations about quality and equity continue, but are there measurable changes that suggest that the experience for patients will be better next year, or in ten years?

On my walks and in my quiet moments I wonder what I might have done that I did not do. I wonder if a more effective leader might have made a difference given the opportunities for leadership that I was given. A core message that I never was able to translate into performance is captured by the difference in perspective between “I want” and “we need.”

In retrospect “I want” drives much of the thinking in the business of healthcare. It is present on both sides of the transaction between systems of care and the populations and individuals they serve. “We need” is always a secondary consideration at the moment. The dichotomy between self and community is at the root of our vaccine dilemma. Progress often requires giving up what “I want” at the moment for the long-term acquisition of what “we need.”The focus on “I want” creates uncertainty for everyone. A focus on “we need” is a better way to prepare for an uncertain future.

As I think about the subjects that I have explored in these notes over the past many years discussing the healthcare implications and appropriate strategies that would be a thoughtful response to the ever present challenges healthcare faces were summarized by the acronym “VUCA,” volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous. My personal effort to advocate for a transformation in healthcare that would promote the objectives of the Triple Aim efforts seems to me to have had not much more benefit than yelling into a desolate canyon. The echoing words fade in volume without any measurable impact. I now share Dr. Batalden’s sense of frustration, and the concern for the future that he articulated to me now many years ago.

I have a bad habit of attaching what concerns me to almost any issue under serious discussion. You can imagine that my Monday morning friends can attest to this trait. The woman in our group who is a retired minister responded to my angst about my professional failures and the current uncertainty about the future of healthcare with a quote from the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke. I vaguely remembered his poetry from some college course I took almost sixty years ago. The quote is from a book in prose called, Letters To A Young Poet. At the height of his poetic success, Rilke wrote ten letters to a young man who had asked for his advice. The letters from the famous poet were saved by the young man who had asked Rilke if he should dedicate his life to poetry or alternatively pursue a military career. Rilke never directly answered the question, but he gave the young man advice that would enable him to answer his own question. The young man later published the letters. In one of the letters Rilke wrote:

“Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books that are now written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.”

Rainer Maria Rilke

I accepted Rilke’s advice as delivered by my friend and then felt even better when I finally got around to finishing Sunday’s local newspaper on Wednesday when I discovered an op-ed piece of similar value entitled “Of squirrels and mental health” written by Dr. Diane Roston of Hanover, who is the medical director of West Central Behavioral Health.

It was one of those pieces that you are not sure you will finish when you start it because it seems to be just a piece about the frustration a woman has with squirrels that raid her birdfeeders, but when I gave it a chance I realized that the squirrels were just a lead-in metaphor. After briefly discussing squirrels, Dr. Roston writes:

At this point in the winter season, my primitive mammalian brain, like the squirrel’s, craves comfort. Comfort food. Warm soup. Sleep. Chocolate. A soft quilt. A cup of tea.

My cortex, in contrast, scans for ways to turn the risk of frostbite into a meaningful opportunity for personal growth. Beyond conventional winter survival advice to bundle up, stay active, keep in touch, the mental health field offers additional suggestions for dealing with this kind of adversity.

OK, I accept her description of the paranoia and annoyance precipitated by the squirrels making persistent efforts to rob her bird feeders might be an introduction to a message with deeper meaning. I use similar introductory maneuvers in my writing. I’ll accept that the squirrels could be a surrogate focus for all of our frustrations. I have shared her experience with squirrels. Long ago, I gave up attempts to outsmart the squirrels that come my way and have chosen to call the feeding devices in my yard “bird/squirrel” feeders. I just hate it when they ruin my feeders by gnawing holes in the plastic to get a “gush” of seeds. But, I am back to being literal and she is moving on.

Reading further, I realized that she was going deeper than frustrating squirrels. She mentioned a familiar name, Dr. George Vaillant. Dr. Vaillant was a force in psychiatry in Boston and at Harvard Medical School for most of the years I practiced. He led a famous study of aging, “The Harvard Study of Adult Development” for over thirty years, The study has been following over 700 adults for sixty years and is now looking at the “second generation.” According to Vaillant’s Wikipedia bio, his current focus of study seems appropriate to my recent distress. Wikipedia says:

A major focus of his work in the past has been to develop ways of studying defense mechanisms empirically; more recently, he has been interested in successful aging and human happiness.

Dr. Rosten referenced advice from Vaillant’s 1977 book, Adaptation to Life. She writes:

As I sip tea from a warm mug, I offer these sips of comfort, these adaptations to life, for cold and challenging times.

A cup of creation (“sublimation”).

Make something. Build, move, improve. Create.

A cup of patience (“suppression”).

Wait it out. Wait for the right time. Hold feelings steady.

A cup of hope (“anticipation”). Look toward the future. Expect better times. Make plans.

A cup of kindness (“altruism”). Put your needs aside to help someone else. Provide comfort to others.

A cup of laughter (“humor”). Laugh at how little we know. Laugh when you can.

Dr. Vaillant would call the terms in quotes “mature defenses.”

I have already placed my Amazon order for Adaptation to Life. A new paperback copy costs $35.00, but I got a good used copy for $6.00 plus shipping. Together, we face very big problems. The perspective from the “Sermon on the Mount” and Rilke is that what we face is just the latest presentation of some chronic problems that collectively we have not yet solved. Each of us has the opportunity to make an effort to add a few stones to the construction of a better future that we may never personally occupy. What is good now was given to us by those who came before us and made incremental contributions to the continuous improvements that have mitigated, but have not solved, the problems that still persist.

I guess it was a naive hope that in my time real and lasting improvements in healthcare equity and the cost of care delivery would occur and that we would move beyond “I want” to “we need” and achieve a universal benefit that was better than what any one of us could want. Like Batalden, I now doubt that will happen before there is moss on my tombstone, but it is my hope that someday our current failures will lead to insights that produce success. That was Martin Luther King’s dream. He said that he had been to the mountaintop and had seen that there would be a better day. Perhaps with King’s vision coupled with resources like Jones and Valliant and so many others that exist but get little attention in a world that is living in the moment, will find that Rilke was right and that we might in time:

…gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.”

Making The Turnaround At Twin Lake Village

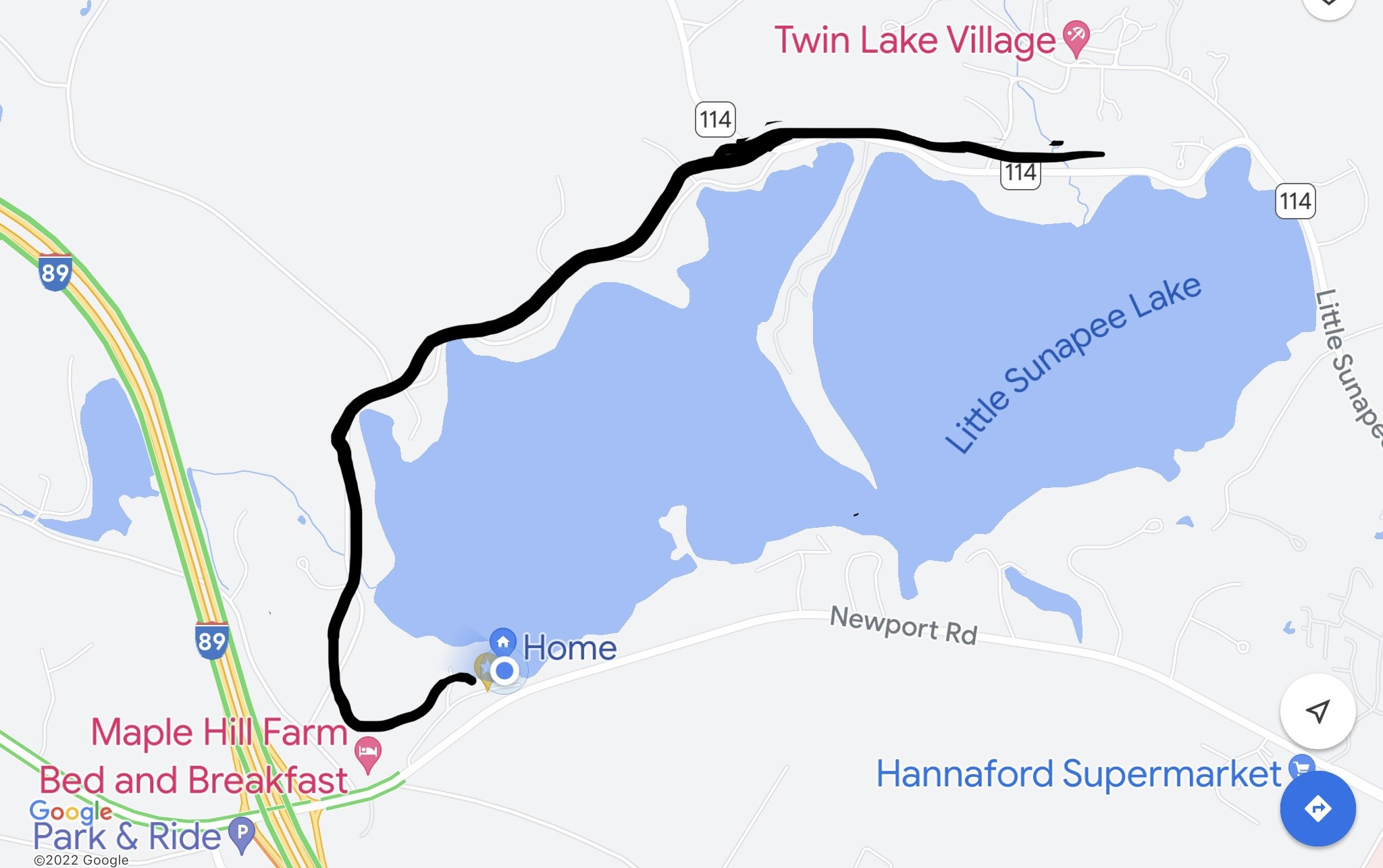

While I am waiting for the world to get better, I find that a little regular exercise is good for my soul. The picture in today’s header was taken last Monday at the point 2.5 miles from my home where I turn around on my trek when my goal is to walk five miles. I figure that when I get to this point success is assured because I must do the reverse trip to get home. Every step adds to the certainty that I will achieve my goal.

I don’t know exactly how many times I have gotten to this point over the last thirteen years but my guess is that it is a four-digit number. If you were to graph the time it takes me to do the roundtrip against the date you would have a study in the natural deterioration associated with aging. In 2008 when I made trip number one I was capable of doing it in about thirty-five minutes if I pushed, and around forty minutes if I was taking it easy. I was running then. I hobble now. On Monday it was a one hour and fifty-nine-minute effort at twenty-five degrees under a partly cloudy late afternoon sky.

The building is the main lodge of Twin Lake Village. It sits on a great little sledding hill that is obscured by the angle of the photo. It’s been sitting there and owned by the Kidder family since the late nineteenth century. It is surrounded by quaint houses that are rentable and that you can see in the many photos on their website. Sometimes people call it Twin Lake Villas rather than Twin Lake Village. The road up to the lodge adds to the confusion because its name is Twin Lake Villas, not Viiiage, Road.

Our lake is officially named Little Sunapee Lake, but most people reverse the last two words and call it Little Lake Sunapee. “Big” Lake Sunapee is a downhill run of about half a mile through two smaller ponds as I described in last week’s note. The brook that brings most of the water to our lake is Kidder brook and it flows down from the hills above over several magnificent waterfalls. The hiking trails along Kidder Brook are a rewarding challenge. If you bring a fly rod you can catch brook trout in the pools below the falls. There is a stone bridge between the last waterfall and the lodge. Brides, lovers, and little children are frequently photographed on the bridge with the waterfall in the background.

This is “new scenery.” About fifteen thousand years ago as the glacier melted, Kidder Brook was formed and changed its channel several times in a fan-like wandering that created a “delta” between the lodge and the lake. The Kidders turned that flat land below the hill where the lodge sits into a par three nine-hole golf course.

The silt from the runoff created a great beach for the Kidders and their guests. The name “Twin Lake” is taken from the fact that the glacier also created a large peninsula that nearly bifurcates the lake. A third less commonly used name for our lake is “Spectacle Pond.” The peninsula is like a nose sporting spectacles. Four years ago a geologist who lives part-time on the lake and has summered here for all his life, put together a complete geological profile of the lake. If you clicked on the link you got a very good discussion of glaciers in general and Little Sunapee Lake in particular. My home sites on the natural “dam” that created the lake and is on the west side of the lake nearer its outflow and marked “home” on the Google map below. I’ve drawn in my route from home to my turnaround at Twin Lake Village.

Not long after retiring to New London and beginning to meet my new friends and neighbors, I started asking the people I met how it was that they “ended up here” in “Heaven’s Waiting Room.” The answers fell into a few groups. By far the smallest number of people who answered my question said that they were born and raised here. A few had gotten to know the area by skiing at Mount Sunapee. A large group was here because they got to know the area when they studied at Dartmouth. A very large number answered that their family had come many times to Twin Lake Village during their childhood and then they had continued to come to the area with their children, so retiring here was like coming home.

In a world with so much uncertainty, a sense of place provides some relief. I wonder if I had a past life experience here.

Be well,

Gene