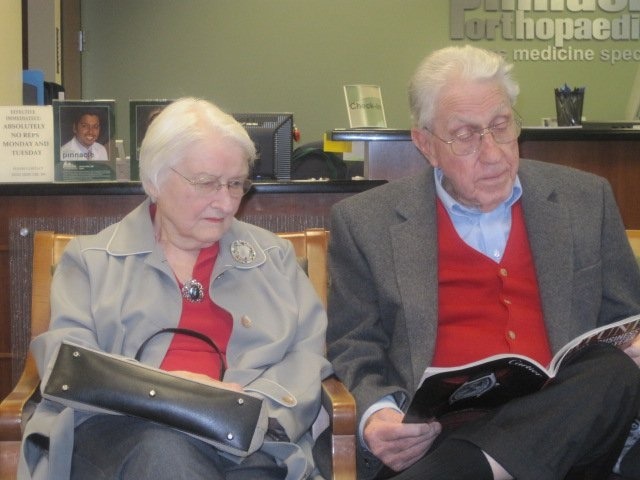

The header for today’s post is a picture of a couple, both in their nineties, who are patiently waiting for a doctor’s appointment. I know a lot about this couple. They are my parents. They were in the vanguard of a growing movement, seniors living into their mid nineties aided by aggressive use of medical devices, surgery and other interventions, and frequent medical appointments for chronic disease management. Perhaps the biggest challenge that must be addressed in the quest for universal healthcare and the Triple Aim is whether we have the resources to give every person access to services that my parents enjoyed.

Let me tell you a little bit about their histories. My mother has a very positive family history of coronary artery disease. Her father died in 1953 at age 64 after a series of myocardial infarctions and progressive disability from CHF. Her brother survived until he was 76. He was benefited by the care advancements of the 60s, 70s and 80s that were not available to his father. He had bypass surgery surgery twice. He had the benefit of improved arrhythmia management, and was the recipient of an early defibrillator/pacer. Most significantly he benefited from the improved medical management of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and congestive heart failure.

My mother was not a smoker like her brother had been. She did share the benefit he enjoyed from aggressive management of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia which began in her 50s. My mother had a LAD angioplasty in her mid seventies, and a pacemaker for management of brady/tachy syndrome with syncope and recurrent slow AF in her early eighties. Through it all she had recurrent bouts of Crohn’s Disease that were managed with steroids, and in her 90s she was debilitated by osteoarthritis of multiple joints. Over the last ten years of her life she probably had at least twenty hospitalizations, and several hundred out patient appointments with her PCP, primary cardiologist, electrophysiologist, gastroenterologist, pulmonologist, urologist, rheumatologist, dermatologist, ophthalmologist, and orthopedist. Going to the doctor became the primary reason for her to leave her home. There is no question that she lived until two months shy of her 94th birthday because of her access to all of the benefits of regular medical care and chronic disease management.

She had an unnecessary cardiac cath at age 92 when she presented with vague symptoms that were probably secondary to early urosepsis, and then spent two weeks in an ICU, initially intubated and on multiple pressors, when she developed post cath septic shock. A year or so after her ICU admission and after several admissions for urosepsis and hypotension, she decided that she never wanted to go to the hospital again, and asked to enter hospice. In hospice, all of her meds were stopped, and for seven months she was more comfortable and interactive than she had been for several years. She died when she began to have grand mal seizures which may have been secondary to a metastasis to her CNS from an undiagnosed tumor, or perhaps from an ischemic event. I am sure that over the last ten years of her life her medical bills were over a million dollars. My parents were fortunate to have the best medical coverage, with virtually no out of pocket expense, which was provided by my father’s former employer, The Home Mission Board of the Southern Baptist Convention.

My father was totally healthy until his seventies except for “Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis.” I have always questioned that diagnosis since he was managed in the mid 1950s with a total thyroidectomy. He took replacement thyroid for the rest of his life. He had a total knee replacement in his early seventies. He was diagnosed with prostate cancer in his mid seventies, and convinced a reluctant surgeon at the Brigham to attempt a nerve sparing total prostatectomy because he was convinced that he was as healthy as a fifty year old man. He was not reassured when an oncologist told him that he would likely die of some other problem before he could die of prostate cancer. He planned to live to be a hundred. He wanted the tumor out. He did live for over twenty years after his prostatectomy without having recurrent evidence of tumor, but he did suffer from post op scaring that required several interventions and much inconvenience which he learned to manage.

After his surgeries, he was very active until his early nineties when he finally discontinued all professional activity and devoted his time to my mother’s care and the work necessary for them to remain independent in their home. After she died, he suffered from depression. He fell and broke a hip. He had a long hospitalization and delayed recovery in long term care before eventually recovering. He had a pacemaker for symptomatic slow AF with rates in the 30s. He fell again coming out of the office of his cardiologist and sustained a pelvic fracture. He recovered and returned to full activity including driving. He took tests to show that he could drive safely. He started dating, and then remarried at age 94. At age 96 he had a massive diverticular bleed that was possibly related to his aspirin therapy. Over the next eleven months, he was in and out of the hospital and rehab with complications from aspiration pneumonia until it was clear that progress was impossible and he accepted hospice care. He died two months short of his 98th birthday. My guess is that the cost of his care, which included very long stays in long term care during the last year of his life, was in excess of a million dollars. Again, all costs were covered by his excellent insurance as long as he had rehab potential. His custodial care in an excellent long term facility that was part of his “life care” living arrangement, after “rehab” was deemed impossible by his doctors, carried a five figure monthly bill over the last few months of his life.

I’ve mentioned the various medical problems and the insights that I gained from observing my parents’ experiences in bits and pieces before. I have always expressed great gratitude for the care that they received, except for a couple of exceptions. My mother’s first pacemaker was attempted at her local hospital in Brunswick, Georgia. Her right ventricle was perforated, and she was transferred emergently to St. Vincent’s Hospital in Jacksonville, Florida. In the end all was well.

There was no excuse for the cath she got at age 92. My parents were frightened into agreeing to the procedure as an emergency. The first I heard of it was when the interventional cardiologist called me from the suburban Atlanta hospital where she was admitted, and asked if I thought she should be intubated, since she was hypotensive on multiple pressors. In my rage I said, “Yes!”, if for no other reason than to give me the time to get from Boston to her bedside before she died.

My Dad’s care was pretty standard until the GI bleed that he got the year before he died. Rather than the conservative approach of discontinuing his aspirin and giving him transfusions, he was subjected to multiple angiograms and endoscopies with anesthesia that left him in a debilitated state. He was discharged before he was stable, and was readmitted with aspiration pneumonia and eventually required gastrostomy feedings for the rest of his life. He was ambulatory and active until the bleed, and never really recovered after the event. He had several admissions during the last year of his life and spent most of the time in the hospital, rehab, or hospice. Would a more conservative management of a GI bleed in a 96 year old have resulted in a recovery? It’s impossible to know.

I do not think the medical histories of my parents are unique. We know that are more than 50 million Americans who are over 50, and 10,000 more of make it to that club every day. By age 85, only 17% of Medicare recipients have no chronic medical problems. Like my mother, by age 85, more than 50% have more than four chronic medical problems. As I mentioned in a recent post, there are serious questions about our future ability to meet the professional needs of this expanding age group that is getting both much larger, and living longer, with more problems. If you click on the link and read the data, you will discover that we have a problem that Medicare For All, and many more dollars than even the most expansive economic predictions can project, can not solve.

Both of my parents benefited greatly from new medical devices and technologies. I am sure that my mother’s life was extended by at least one decade, if not longer, by the initial cardiovascular risk factor management of her cholesterol and hypertension. She was a vigorous walker until she was limited by her arthritis and debilitating symptoms, and her Crohn’s disease forced her onto steroids. Unfortunately, both of my parents also suffered from medical errors and medical decisions which when subjected to my “Monday morning quarterbacking” seem ill advised. My siblings and I were fortunate to have had them as long as we did, so I will take the sum total of the positive and negative events, but that is not the end of the analysis or the message that is embedded in their story.

Each time I have mentioned my parents and their medical encounters in previous posts, my primary objective was to address the issue of equity. I knew then, and I know now, that they had access and financial support that were extraordinary compared with millions of Americans. Time will tell whether or not the political process will solve the “theoretical” access and equity issues that will make the access that they enjoyed available to every American. Having the “coverage” that entitles one to access does not guarantee access or equity, especially if there are shortages of professionals. The outlook is not good. The last link above is to a AAMC report about physician shortages, and their considerations are worth presenting to you:

- The projected shortage of between 46,900 and 121,900 physicians by 2032 includes both primary care (between 21,100 and 55,200) and specialty care (between 24,800 and 65,800). Among specialists, the data project a shortage of between 1,900 and 12,100 medical specialists, 14,300 and 23,400 surgical specialists, and 20,600 and 39,100 other specialists, such as pathologists, neurologists, radiologists, and psychiatrists, by 2032.

- The major factor driving demand for physicians continues to be a growing, aging population. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the nation’s population is estimated to grow by more than 10% by 2032, with those over age 65 increasing by 48%. Additionally, the aging population will affect physician supply, since one-third of all currently active doctors will be older than 65 in the next decade. When these physicians decide to retire could have the greatest impact on supply.

- The supply of physician assistants (PAs) and advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) is projected to continue to increase. The report models their role in providing health care. Further research is required on the types of services these professionals are providing, and if, or at what point, the supply of PAs and APRNs will become saturated.

- Emerging health care delivery trends designed to improve overall population health do not have a significant effect on physician shortage projections. The report’s first-time analysis of emerging health care delivery trends, including providing better care coordination across settings, reducing unnecessary hospitalizations and emergency visits, increasing use of advanced practice providers, reducing obesity and tobacco use, and applying managed care models and risk sharing agreements such as Accountable Care Organizations, only reduced demand for physicians by 2032 by 1%. This analysis is presented as new work and will be refined further before being included in future overall shortage estimates.

- The United States would need an additional 95,900 doctors immediately if health care use patterns were equalized across race, insurance coverage, and geographic location. This shortage would be in addition to the number of providers necessary to meet demand in Health Professions Shortage Areas as designated by the Health Resources and Services Administration. This additional demand was not included in the production of the overall shortage ranges.

- While rural and historically underserved areas may experience the shortages more acutely, the need for more physicians will be felt everywhere. The overall supply of physicians will need to increase more than it is currently projected to in order to meet this demand.

This is a report with no upside. There is a faint hope of some amelioration presented in the paragraph about PAs and APRNs, but it is my understanding that the current population of these professionals plus those that could be trained in time to meet the challenges of 2032 does not solve the access problem. It is also likely that the workforce shortages that exist now are surely contributing to the pervasive symptoms of burnout and work overload that may be resulting in some physicians and nurses either giving up direct patient care or retiring early.

The fourth bullet point reads “Emerging health care delivery trends designed to improve overall population health do not have a significant effect on physician shortage projections.” As the paragraph continues, it suggests that interventions and innovations up to now do not solve the problem. Reorganizations of care like the “medical home,” and ACOs help, but are not enough. So far, insights from population health management have not generated strategies that have yielded enough benefit to solve the workforce problems. Value based reimbursement and risk bearing contracts may have the positive potential to drive innovation, but so far our tentative finance changes have not been enough to solve the looming problems we have now, or will have in 2032.

I think that it is true that if we deploy all the PAs and APNPs we can possibly produce, if every practice in the country reaches certification as a Medical Home, and if fee for service practice was abolished in favor of value based reimbursement, we will would still have the same workforce threats to optimal care that we have now, unless we transform the way we deliver care and better leverage the professionals we have. There is some hope for improvement through both the expansion and application of technologies like AI, but I feel that the greatest potential for improvement lies though low tech changes in the methodology of practice, and in the expansion of self care.

This last March, the National Academy of Medicine issued a report written by Mark B. McClellan, David T. Feinberg, Peter B. Bach, Paul Chew, Patrick Conway, Nick Leschly, Greg Marchand, Michael A. Mussallem, and Dorothy Teeter entitled “Payment Reform for Better Value and Medical Innovation.” The ACA contained the possibility and the hope of innovation in care delivery that might lower the cost of care. It is clear now that innovations will be required to avoid the huge disruptions in care, reductions in service, and increases in expense associated workforce shortages.

It is a startling reality that over 85% of healthcare spending is on chronic disease management. That fact alone may explain why CVS is developing its Health Hubs, and Walgreens and Walmart have their own primary care and chronic disease programs in development. These disruptors may offer care for less, but unless they are working on ways to use alternative professional labor sources to deliver care that is now provided by physicians, APRNs, and PAs, we have just moved the service to a different venue.

My own opinion, which is just an assumption based on a long experience in practice, is that the model change that is most likely to make a difference is the use of health coaches, intensive programs of education in self management, and “Shared Medical Appointments” to better leverage our professional resources. In retrospect, as I look over the decades of my own practice, those patients that practiced self management achieved the best outcomes. My goal was more than to “share decisions” it was to transfer much of the decision making to the patient and be available to them to support them in their uncertainty. In shared medical appointments I saw patients sharing management information with one another in a much more effective way than I could have done in an one on one encounter. An important part of my role in the shared appointment was to participate in the exchange, and use my comments and questions to emphasize important learning points.

I can remember rounding as an intern, resident, and cardiology fellow with the great cardiologist, Dr. Bernard Lown. In the era of my training a “non transmural myocardial infarction” bought the patient at least two weeks in the hospital. A “Q wave” producing “transmural infarction” resulted in a three week hospital stay. Dr. Lown frequently compared the weeks in the hospital to a crash college course. He spent an enormous amount of time on our rounds educating the patient, which indirectly educated us as we listened. After we would leave the patient’s room and move down the hallway out of the hearing of the patient, he would review with us the points of information that he was attempting to transfer to the patient. In those days we had hospitalization rates of 900-1000 hospital days per thousand patients. These days the numbers in well managed systems are a tenth or less than those numbers. The reduction in hospital days is laudable, but loss of time for the educational interaction with the patient at the bedside should be replaced in some other way. The fifteen to thirty minute office visit with all of the administrative issues and record creation that must occur in the same time frame leaves little time for effective information transfer that enables self management. The “after visit summaries” are often “boilerplate” productions that are of minimal value other than for medical legal protection. There are opportunities to better leverage our existing medical professionals, but I suspect that the biggest issue will be the acceptance of the establishment of need to change traditional roles and responsibilities.

My fear is that over time the inequities that currently exist in access to care will grow, not because of inadequate financial resources, but rather because of professional shortages that will impact the care of patients of all ages, and will undermine our desire to improve the health of the nation. I am reminded of a science fiction thriller from 1976, “Logan’s Run.” Wikipedia summarizes the plot:

It depicts a utopian future society on the surface, revealed as a dystopia where the population and the consumption of resources are maintained in equilibrium by killing everyone who reaches the age of thirty. The story follows the actions of Logan 5, a “Sandman” who has terminated others who have attempted to escape death and is now faced with termination himself.

I do not mean to imply that someday we will have such resource shortages that we will set an age after which optimal care is no longer possible for every person. We would never do that, but we can get to the same end result that reduces access to needed care for every person, no matter their age, unless we begin to focus on how to eliminate the waste and improve the efficiency of how we deploy our professional resources. As resources become dearer, only those with the ability to make “private” arrangements similar to concierge care will have access to the comfortable and convenient care they desire.

My parents were mostly fortunate. They had access to very frequent office visits with mostly competent clinicians. I am sure that the care they enjoyed will still be available for a while yet for those of us who are lucky enough to be able to buy it, or for the very few who have an extremely generous former employer who that offers spectacular retirement benefits. My parents had both their own adequate resources, and a generous retirement plan, but the numbers suggest that the future will put more and more of us who live in the vast middle of economic opportunity and resources into a status that is more like the care of our underserved population. The upper tier of care will have proportionately fewer beneficiaries as more and more of those who are now comfortable with their care discover it is harder to get an appointment with their usual coverage because there are just not enough clinicians to give them the appointment they need. The emerging problem that I have tried to described can only be solved by those who are leading and are participating in the delivery systems across the country that provide care. Public finance can encourage the right outcome, but the answer to the problem can only come from its practitioners and leaders. If you are a healthcare professional, you have work to do.

Wonderful piece, Gene. An intimate sharing of personal, familial experience that would inform policy. Beautifully done. There’s most certainly a long magazine piece in this!