My wife had a simple mantra that she repeated each time our boys left the house to go out with their friends. She would say, “Make good choices!”. Her inference was that there was loss associated with bad choices. Never before have patients, families, doctors, other healthcare professionals and medical organizations had more important choices to make than now. Like the circumstances that potentially surrounded the choices that our boys would have in the outside world away from their home, the choices offered to the participants in the grand drama of healthcare reform all involve risk and the potential for loss. It would seem prudent for us to understand how we commonly make errors when we are asked to make a choice in the context of possible gains and the risk of potential losses in an environment of uncertainty.

In healthcare reform no one is just a spectator or gets a bye from the necessity of making choices. There are difficult choices for patients who must make decisions about the trade offs between costs, benefit packages, and coverage and who they will have access to see. Doctors must make choices not only about what treatments to employ but also make economic choices about which insurers to accept whether they will see Medicaid and Medicare patients or whether they will be self employed or become salaried in a system.

Since the passage of MACRA doctors, hospitals and health systems must add complex choices about what path they will follow into the future of value based reimbursement. Organizations must decide whether to prepare to participate in alternative payment models (APMs), focus on the merit based incentives (MIPs) option or just continue to accept fee for service reimbursement with little chance for anything but a continuous decline in the future in their income from Medicare. All healthcare organizations operate in an uncertain environment where the politics and regulations can change quickly.

Commercial insurers and CMS are pushing doctors and healthcare organizations to chose to accept more risk as well as understand more about population health. There are choices and decisions to be made about how to respond to these demands. Some wonder if this is a passing trend that can be ignored. Perhaps the shift from FFS can be resisted. Would it help to elect a business friendly president? On the other hand, perhaps fee for service has passed a point of no return and every moment of delaying in preparing for value based reimbursement, risk, and population health will just increase an organization’s vulnerability for future losses that are guaranteed if they delay.

Every healthcare board, every healthcare executive, and every healthcare professional needs to weigh the risks and benefits of preparing for changes that looks like they will come, but when? The future of FFS will be determined by the sum of all the forces and all the choices that are interacting in the ongoing drama. The emotion that heightens the tension behind all of these choices is the fear of the losses associated with making bad choices. What makes it all so hard is the variability in strengths and weaknesses that we bring to the moment in terms of mindset, experience, ability to tolerate uncertainty and individual appetites for risk.

We all have powerful aversions to risk, potential loss and all things that move us from the comfortable set point of the status quo. We highly prize what we currently have (endowment) and are not easily persuaded to trade it in on what someone, whom we do not fully trust, tells us will be better. Only two groups naturally embrace movement from the status quo. The first group are those for whom the status quo is already an unacceptable loss. The second group is a coalition composed of those who are profoundly troubled by the deficiencies in care that they see and those who see the potential for ultimate loss for everyone when the metastable systems of current care, replete with their inequities in access and quality, eventually collapse.

Insurers and CMS have been struggling for years to find ways to “buy back” the choice enshrined in Medicare and most employer sponsored health insurance. These “buybacks” have all been alternative manifestations of choice like Medicare Advantage and health spending accounts.These programs are forms of gentle “persuasion”. Persuasion, whether in the form of the “deals” described or the exhortations of the concerned has produced some progress when attached to aligned legislation and regulatory changes. For over twenty years now organizations like IHI and the IOM, as well as CMS and many specialty societies, have been trying to persuade all of healthcare to improve quality, safety and patient satisfaction while lowering costs.

“Persuasion” alone increased awareness and yielded some benefit. Persuasion plus incentives were enshrined as “pay for performance” and further improved the yield on measured quality but did nothing to lower the cost of care. Persuasion plus a little regulation has produced some progress in access but has not produced much improvement or only temporary improvement in cost as pointed out by Marcia Angell in her recent opinion article in the Boston Globe. Medicare for all as advocated by Bernie Sanders and Dr. Angell is still a “bridge too far” for those comfortably ensconced in the status quo. Dr Angell even has technical problems with Hillary Clinton’s “Medicare for More”.

For physicians and organizations “choice” is becoming a dilemma, a choice between unacceptable alternatives. “Choice” has morphed from accepting pay for performance or not, to a choice between less pay for performance and more risk for not performing against a combination of economic and quality measures. For patients “choice” is already costing them more. With MACRA “choice” has the potential of yielding losses. Choice has been one explanation for why healthcare has not followed the rules of a traditional marketplace. Will less “practical choice” from the implementation of choices with sure losses create a marketplace?

For some time I have been intrigued by the evidence that behavioral economics and the practitioners of the “softer management skills” could offer us explanations to help us understand how people make choices. Writers like Dan Ariely, Richard Thaler, Cass Sunstein and even Malcolm Gladwell and Daniel Pink had a lot to teach us. In 2011 I was delighted by Thinking, Fast and Slow, the masterpiece by Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman. Recently I have been rereading sections and it occurs to me that especially in Part IV: Choices, Kahneman is speaking directly to us in healthcare today. His descriptions of loss avoidance, risk aversion, prospect theory, and endowment align directly with the difficult choices/decisions that patients, healthcare professionals and healthcare organizations are being compelled to make now and will need to make with increasing frequency in the future. His focus on affect as a determinant of choice is powerful. You might enjoy a YouTube conversation recorded between Sunstein and Kahneman at the Harvard Kennedy School in 2014.

I see a connection between “adaptive change” as described by Dr. Ronald Heifetz at Harvard’s Kennedy School and behavioral economics. Adaptive change is hard because of the losses that are induced by change. A big loss is giving up a domain, the status quo, where you are an expert and having to move to a new operating system where you are an inexperienced “Newbie”. By mid career most of us are very comfortable on the long upper plateau of our professional learning curve. Healthcare reform asks us to give up this comfortable position which is working just fine for us, thank you, and move to the foot of a new learning curve where we will be clumsy and inefficient for sometime to come, all for the greater good.

A stress or sacrifice like moving to a second curve is a real loss and the feelings of denial and anger followed by resistance/depression before bargaining and acceptance generally follow the five step grieving process described by Kubler-Ross. The sense of loss is compounded by the fact that a focus on money and other business issues that we lump under the rubric of “efficient-effective” seem at odds with clinical values that we tell ourselves have not had to change much, other than an upgrade by giants like Osler, since the days of Hippocrates.

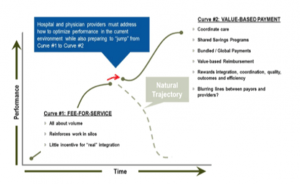

The image below which I have used many times in the past emphasizes not only the move to the base of the new “learning curve” (remember the need to learn is fatiguing and part of the sense of loss associated with adaptive change) but it also demonstrates the “compulsion” that is driving the movement:

The image shows the assumption that fee for service reimbursement is going away to be replaced by value based reimbursement which is a euphemism for more performance risk and much less certainty about revenue. As I mentioned in my piece about Br’er Rabbit, I do view risk as an opportunity, but for most healthcare professionals reimbursement with risk is mostly uncertainty and loss.

Kahneman and his colleagues focus on the fact that we want “sure things”. The sure thing of a lower monthly payment of a “bronze” plan may be great as a way of avoiding an immediate monthly financial loss for a healthy young person but an irrational gamble for a person who is a diabetic or has recurrent issues in behavioral health. Accepting an upside only contract as a group practice may feel comfortable as a way of “getting our toe in the water” but in fact may be a disastrous delay in developing the infrastructure and experience to manage risk and be able to profit from accepting a budget for the care of a population.

Kahneman and his colleague Amos Tversky are the originators of “prospect theory”. MACRA is nothing but raw prospect theory on steroids. Prospect theory explains how we think and approach choices when we are ask to decide between alternatives that involve risk, as we are in healthcare, where the outcomes are uncertain. MACRA is also an example of the “framing effect”, which says that we react to a choice based on how it is presented as a potential gain or loss. We often accept what we believe to be a survivable loss even when we are offered an acceptable risk for an upside gain where risk can be diminished by experience and competence. Since we like to be presented a sure thing compared to a risk, we usually accept risk only when unacceptable losses are the alternative or when we are offered no other choice. I think this is the most obvious place where we see the “nudge” in MACRA. You can choose to stay with FFS where you are comfortable, but with certain future losses compared to current revenue.

Kahneman emphasizes that the “set point” or status quo determines how we react to our choices. We like what we have and emotionally tend to see more value in what we have than actually exists. Perhaps it is the “endowment effect” that explains our attachment to our current management practices, familiar bricks and mortar, and comfortable but inefficient workflows rather than seeing opportunity in new operating systems and tools for an innovative future. You do not choose what you do not see.

I am not going to be able to make you into a behavioral economist within the limits of this essay. Perhaps I can persuade you to look at how you consider the choices that you are offered as an individual or as part of an organization. Like my wife, instructed our boys, your future is dependant on making good decisions. The options may not really be what they appear to be when you make a snap judgement. Thinking differently with a slow deliberate approach to your options while considering your bias for the status quo may be the formula for success on the second curve in the era of compulsion.