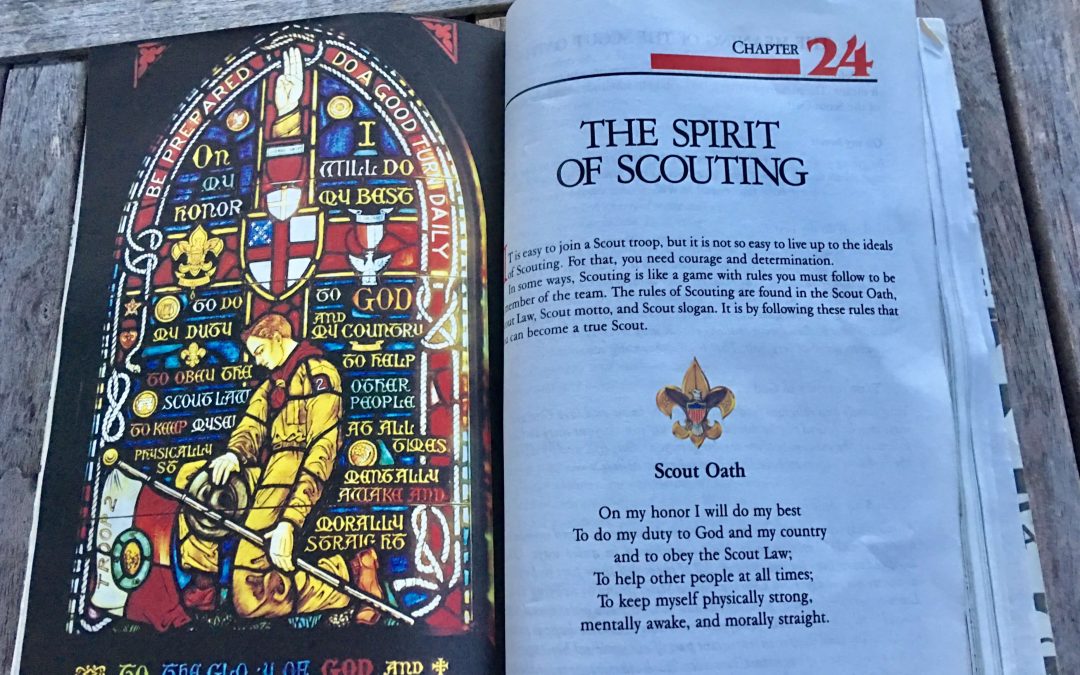

What floats your boat and moves it? Perhaps that is a crude way of asking about both where your values arise and what motivates you. For some reason whenever issues of either values or motivation become the subject, I think of my experience as a Boy Scout. I sometimes say that I was a highly motivated Boy Scout until I became a girl scout. I loved the outdoor lore, and I totally accepted the values that were presented. What shifted my major interest away from scouting was football, but then again one of the reasons I was interested in football was the cheerleaders. I think that the reality is that puberty was what turned my head away from Scouts and toward the larger world. Despite the fact that I never became an Eagle Scout, I do look back on my experience as a Scout with fond memories of campouts in the hill country of Texas, campfire sing-a-longs, and week long trips with my troop to the camp maintained by my area council where I learned how to paddle a canoe and was jump started on many “merit badges.”

The warm feelings and fond memories that I have from scouting are very similar to the feelings that are associated with my years in medical school, my post graduate years as an intern, resident, and fellow, and my early years of practice at Harvard Community Health Plan. What motivated me through all of those years was the fascination of learning the craft and science of medicine, the sense of collegiality in the groups in which I was a member, and eventually the values and ideals of the organization that I joined. Those values and ideals of our practice, Harvard Community Health Plan, were highly aligned with my own values. It was great to be supported to be a better physician within an organization that realized that healthcare need to be improving, and could improve. That was in the seventies and early eighties. Something happened in the mid eighties that changed my world.

In retrospect what happened between 1985 and 2005, was that our organization became more and more manipulated, and in essence motivated, by external marketplace challenges. Those external challenges were delivered as financial realities that were derivative of employers choosing to “sole source” their purchases of healthcare and the reality that a lower price and higher quality were not enough to compete with a “brand” that had the national reach and convenience of Blue Cross and the other large commercial insurers. As our motivation was modified and shifted more and more by external realities, the internal “values” that were so essential to our sense of who we were became harder to maintain and defend.

As I look back on our practice in the seventies and early eighties, I can’t remember discussions about “individual productivity.” If they occurred perhaps they were secondary to conversations about how to improve the care that we were providing together. Our “productivity” was not connected to our compensation. We collectively accepted the risk of our ability to perform together. We did have “work expectations” that described the number of hours we committed to work in the office, our hospital rounding responsibilities, our commitments to “citizenship” activities such teaching and support of our staff and students, and our “on call” expectations.

If you were in practice in the early nineties, you probably remember the introduction of RVUs. If you remember when you first heard about RVUs you may remember your confusion or resistance to the idea of having your compensation become a function of the number of “widgets” of care that you produced. You may even remember how your approach to practice and your medical record keeping were modified by the new motivation of maximizing the RVU credit of any encounter. If you became a medical professional after the mid nineties it is highly likely that you have never worked in an organization where the funding was independent of the sum of the collective activities of its providers on its population as measured by RVUs.

The value of RVUs for Medicare and Medicaid are determined through a process that is a negotiation among Congress, CMS, and the RUC, a committee of the AMA. Some of us believe that one reason that primary care is so undervalued is that the RUC is largely populated by medical and surgical specialties. The value of commercial RVUs is determined by negotiations between delivery systems and payers. A “conversion factor” multiplies the dollar value of Medicare RVUs. A commercial contract will often pay more than twice as much for an RVU as will Medicare. What an organization can negotiate from a payer is a function of its “market power.”

It is hard to imagine how those “Boy Scout” and initial medical school values can withstand the distractions introduced by external financial forces and the motivation and alternative values that they drive. It has always been interesting to me that a significant number of “employed physicians” are totally unaware of the mechanics that determine both how their organization is paid and how in turn they are paid. More importantly, they are often blind to the ways in which they are paid drives the way they spend their time and distracts them from the values that they brought to practice. Perhaps the biggest overall challenge in the shift from volume based reimbursement, which is RVU dependent, to value based reimbursement is managing the shift away from RVU compensation.

Craig Samitt, who recently became CEO of Blue Cross in Minnesota, was once CEO of Dean Health in Wisconsin, and long before he led Dean, he was my colleague at Harvard Vanguard. Over the years after Craig moved on, I would see him at meetings of the Group Practice Improvement Network, GPIN, where he often served as moderator of the open discussions about “hot topics.” I loved his ability to lead these emotion ladened group conversations, and his ability to use his experience and wit to make important points. Year in and year out, the “hottest topic” was physician compensation. Craig used humor to evolve the concept of “funky physician compensation.” The land of “funky comp” is where most organizations live. Increasingly they are signing value and risk based contracts, but are still trying to maintain physician compensation programs that are volume based (RVUs). The result is conflict and confusion of objectives. It is my opinion that some of the difficulties related to demonstrating the value of ACOs is the reality that most of the physicians in ACOs are still paid through productivity programs that are RVU based. This is especially problematic with care paid for by the ACO to outside organizations and their specialists.

The transition from Boy Scouts to physician compensation may be confusing for you, but I see the transition to ACOs, value based contracts, and the process of change that is being driven by MACRA, as an opportunity to reorient how physicians are paid toward a more positive relationship between professional motivation and personal and organizational values. As I have frequently said, Don Berwick’s Era 3: The Moral Era is aligned with this positive shift that supports the Triple Aim. The “moral injuries” of physicians and the relationship of those injuries to “burnout,” the discussion of a recent post on this blog, both would surely benefit from a shift away from RVU based volume assessments of productivity.

Physician compensation has been an interesting subject for me since the late 80s when I was the chair of the compensation committee of our practice. What I learned then was that no matter how ill aligned a comp program may be with both the internal values of the group, or the issues that drive the national conversation, many doctors are reluctant to accept any changes in the way they are paid. We embrace and are reluctant to give up the dysfunctional processes that we know and understand. A quick Google search will demonstrate that the conversation about how to align physician compensation with value based reimbursement has been going on for a decade, and yet most organizations are still unable to shake the habit of RVU based programs of compensation. There is a whole new market of consultants willing to offer their advice to organizations who are struggling to align their compensation programs with the new value based payment mechanisms.

I was excited back in 2009 when Daniel Pink’s book Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us reiterated a point made several decades earlier by Peter Drucker, that “knowledge based workers” were not effectively motivated by productivity based compensation programs and bonuses. Doctors and other healthcare professionals are the quintessential “knowledge workers.” Most of us came to our profession with a set of values and objective that fit the philosophies that we absorbed in our formative years as Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts. Those values and the hope that someday we might contribute to the health and welfare of the people who came to us seeking relief from pain and suffering did sustain us through long days and nights of training. We are the kings and queens of delayed gratification. Yes, we expected a middle to upper middle class compensation, but most of us were realistic enough to know that if great wealth was our objective, business school and a career at Goldman Sachs was a better strategy than even a residency at a premier academic medical center could set up for us.

Recently, I have referenced Johann Hari’s book Lost Connections: Uncovering the Real Causes of Depression–and the Unexpected Solutions which describes how the external challenges of modern existence separate us from the communities that sustain us, and cause us to lose the connections with our internal motivations and values that we evolved to succeed as a species. If you read the book while holding the challenges that face today’s healthcare professionals in mind, it is easy to see that getting paid more to do more is likely to separate even the most dedicated and service oriented individual who ever graduated from medical school from their intrinsic values or motivations to be patient centered. Volume compensation can refocus their values and motivations toward the values and motivations that promote commercial success that they might never have ever possessed if the external world of healthcare finance had not driven a different orientation to the world of patient care.

Flannery O’Connor who contended with the challenges of lupus for most of her short adult life used the phrase, “The life you save may be your own” as the title to one of her most famous short stories. It would be a stretch to connect her story to the subject of this letter, but the title fits nicely as a warning to today’s healthcare professionals. The future of practice, the care our patients receive, and the emotional and professional wellbeing of healthcare professionals is dependent upon an awakening of the values and the motivations that drove so many of us before the events and momentum of the last thirty years put so much focus on false concepts of productivity.

I am not advocating a return to the past, and I am not suggesting that we forget our responsibilities to be productive. I am suggesting that as we reengineer our practices with innovative ways of delivering care, we must be good stewards of scarce resources while we search for new ways to work to make all care conform to the concept that patient centeredness, safety, efficiency, effectiveness, timeliness, and equity define what is really the quality we offer. We must save our own lives by returning to those motivations and values that may sound hokey in a commercial context, but ring true with those who come to us hoping that we might be able to help them. I hope that before it is too late Boy Scout like motivations and values will come back into vogue and provide the motivation we need to make the Triple Aim a reality.