It feels like we have had a lifetime’s measure of challenging events in the last four months, but it seems much too early to know how things will be different when the “new normal” really arrives. The descriptors of this moment are volatility, uncertainty, and fear. As humans we like explanations for why things occur. Our ancestors created stories to explain the origin and workings of a world that they did not understand. Since we have become “enlightened” we have gained the ability to manage more and more or what might happen. Our problem, as Atul Gawande has said, is not that we are ignorant. He says that now our problem is that we incompetent.

I agree with Gawande at the 40,000 foot level, but I think the answer to why we don’t take full advantage of what we know and have the power to learn is more complex than simple incompetence. I also believe that though we are no longer ignorant of the facts we are often resistant to applying the knowledge we have gained to the problems at hand. That resistance often arises from the conflict between self interest and what would be best for the community. In essence that is the problem that Al Gore described in his documentary and book on climate change, An Inconvenient Truth.

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed several more inconvenient truths and areas of collective reluctance to act. The pandemic did not cause healthcare disparities, but it did reveal how they impact everyone. COVID-19 did not cause us to underfund public health, fail to create adequate stockpile of critical medical supplies, or negligently undermine our defenses against potential pandemics, but it revealed that we had done all of those things. The COVID-19 pandemic did not create the inadequacies of a fee for service system of healthcare finance, but it did reveal that it is more important to fund healthcare in a way that insures the care of populations than it is to maintain a system that has evolved to insure a seven figure incomes for some interventional specialists and healthcare executives.

The death of George Floyd was not a unique event. We have a long history of deaths arising from the tensions between the police and the public that is a disproportionate burden on minorities. In 2019, 1004 people were killed by the police. A disproportionate number were Black or Hispanic. The argument that is used to justify those deaths is that “police work” is dangerous and the use of lethal force is justified to protect the public servants who do this dangerous work. Indeed, the FBI reports that in 2019 the police suffered 89 deaths of which 48 were the result of “felonious acts” and 41 were from accidents. Many have observed that some of the carnage on both sides can be explained by the fact that the role of policing has been expanded into areas where the expertise and training of the police is inadequate to the task. Few policemen are trained to manage domestic violence or episodes of violence that arise out of mental illness or substance abuse.

The Black Lives Matter movement began in 2013 after George Zimmerman was acquitted of murder following the shooting of Trevon Martin. Why did not the deaths of Michael Brown and hundreds of other Black Americans between 2013 and 2020 cause the same sort of response that followed George Floyd’s death? There is at least a temporal relationship between the sudden surge in acceptance of the importance of the concept that Black Lives Matter and the realization that the pain and loss of the pandemic has fallen most heavily on the population that is most at danger from dysfunctional policing.

Something has made this moment different. There are many signs that point to the possible birth of real change. The demonstrations have continued for a month when in the past they lost momentum in a few days. Businesses have changed long standing logos that are insensitive to race. The NFL has apologized for its insensitivities to legitimate acts of protest. Mississippi is on the brink of removing the emblem of the Confederacy from its flag. Statues that are reminders of a disgraceful past are coming down. The names of prominent men, even a president, who were racist or slave owners are being removed from buildings and institutions. Many cities are on the brink of redefining policing. Did these things occur now because of the temporal relationship between the filming of the death of Mr. Floyd and the heightened emotions associated with the pandemic, or are they connected in a more direct way? Will the events that have transpired lead to a sustained movement that produces permanent changes?

So far, nothing that has happened in our ICUs or on our streets guarantees future improvements in healthcare or an end to the inequalities that are the outcome of four centuries of racial injustice and abuse. The third unexpected event of 2020, the damage done to the economy and the possibility of continuing economic instability for years to come that is the result of efforts to limit the spread of COVID-19, could become the reason that we will fail to improve healthcare, and the diversion toward self interest that undermines the effort to move toward Martin Luther King. Jr.’s “dream.” If focused self interest has blocked us from saving our planet, could it also not prevent real change from being the positive outcome of our current miseries?

One thing that we learn in the practice of medicine is the frequent connectedness of problems. As I wrote in a post over a year ago entitled “Improving the Health of the Nation Through The Green New Deal,” we can divide the world of clinicians or into “lumpers” and “splitters.” I am usually a lumper. I see connectedness among issues and solutions. I like the concept of trying to find the set of solutions that solves several problems simultaneously. I see a deep connectedness between the pandemic, the economic collapse, and the racial tensions that have existed for centuries. I also believe that the connectedness between them requires that they must be addressed together as manifestations of a larger central issue.

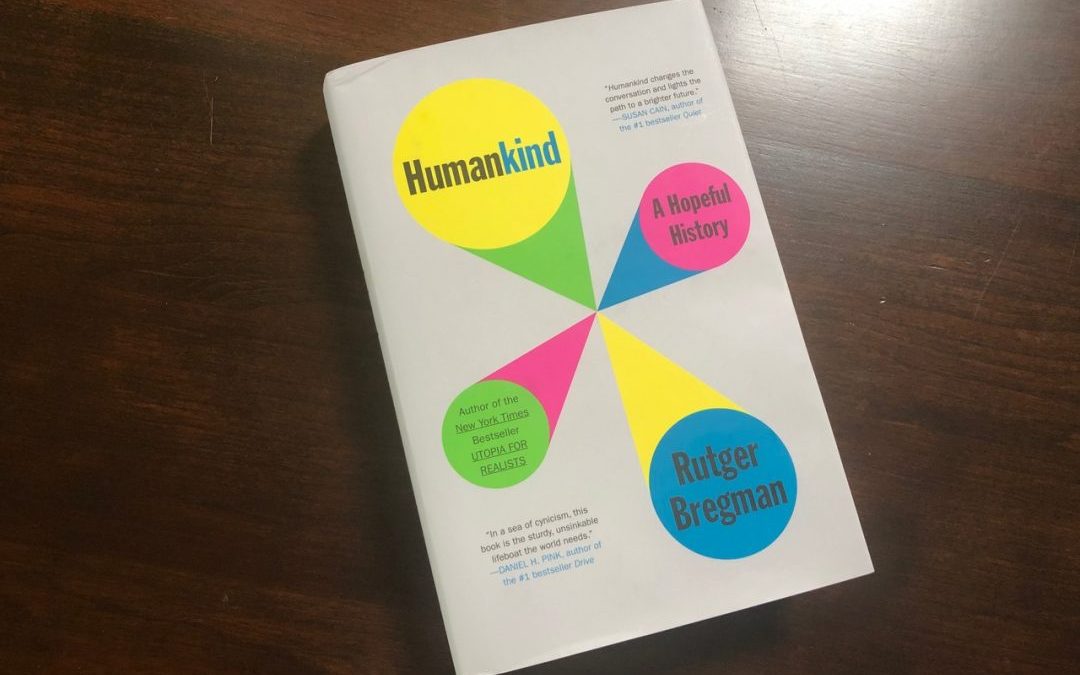

I have recently been reading Rutger Bregman’s fascinating new book, Humankind: A Hopeful History. Bregman is a Dutch historian, journalist, philosopher, and author who is perhaps most famous for an eight minute interview with Tucker Carlson that Fox News never aired, but has had almost 3 million views on YouTube. Tucker sought to interview Bregman because when Bregman was asked to speak at the annual Davos meeting of the captains of industry and finance he castigated them for their ability to avoid paying their fair share of taxes, and then coming to a meeting to discuss climate change in their private jets. (Click on the link to hear Bregman deliver his condemnation in a respectful fashion.) When Carlson tried to interview him, Bregman lumped Carlson with the Davos billionaires as their high paid pawn in such an effective way that Carlson lost his composure during the interview and resorted to obscenities. The interview made Bregman a celebrity in progressive circles. I first learned of Bregman from a recent podcast interview that he had with Ezra Klein.

If you don’t have an hour and a half to listen to the interview with Klein, I would suggest reading a terrific review of Humankind in The Guardian. Just in case you pass on that option, here is what I need you to know:

The book declares that political debate for centuries has turned on a critical argument about human nature. In one corner stands Thomas Hobbes, insisting that, left to their own devices, people will turn on each other in a “war of all against all”: they need the institutions of civilisation to restrain their otherwise base instincts. In the other corner stands Jean-Jacques Rousseau, countering “that man is naturally good, and that it is from these institutions alone that men become wicked”.

Bregman charts how Hobbes won the argument. Society and its key institutions –schools, companies, prisons – have been designed based on a set of bleak assumptions about human nature. But, Bregman says, the scientific evidence suggests those assumptions are badly flawed, that as a species we’ve been getting ourselves wrong for far too long.

So, that may be interesting, but what does Bregman have to say to this moment when we have a pandemic with associated challenges to the economy, and an exacerbation of long held racial tensions, all against a background of global warming. If Hobbes was right and we are brutes that need the constraints of a conservative, and at times authoritarian, system to hold our passions in check, is the answer more police and the reelection and further empowerment of Donald Trump and the crowd that he fronts for? Bregman says an emphatic “No!” Hobbes was wrong, but we have been duped into thinking that we are rotten to the core and need to be managed to prevent us from going off the tracks and descending into chaos. Bregman argues that Rousseau was the one that was right, and that we can choose to recover from the abuse of the Hobbesian lie which has enabled a few to extract great wealth from everyone “below” them. Most of us do care about our neighbor. Most of us care about the future of the planet. Most of us can learn to look past the color of skin and focus on character as Dr. King suggested in his dream:

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

Far and away, the most positive aspect of the horror and fatigue of the pandemic has been the humanity demonstrated by the caregivers. Their stories of heroism and devotion to the very ill have been underlined by the public expressions of thanks coming from the community. These actions stand in sharp contrast to the snarling pronouncements of the president’s personal accomplishments which exist only in his mind and in the factitious analysis that is frequently offered by Mike Pence and some governors who care more about Trump’s reelection and the power that they derive from association with him than the health of the nation.

It is no accident that the subtitle for the book is “A Hopeful History.” Bregman is a great writer and storyteller who had me hooked on his idea of the basic positivity of our species from the “Prologue” which focused on the amazingly positive response of British citizens to the German Blitz and Churchill’s honest assessment of what lay ahead and the promise he gave every person in the nation of “blood, toil, tears, and sweat…” Perhaps it is good to remember that the world has seen honest, straightforward leadership that called a nation to rise to a challenge. Churchill gave us a picture of leadership in his famous first speech to Parliament in May 1940 after Neville Chamberlain had failed in his strategy of appeasement. (Click on the link to hear Churchill’s five minute speech and witness the way a real leader speaks to an enormous challenge). If you don’t have the time, here are the most important lines:

“I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat”… “We have before us many, many long months of struggle and of suffering. You ask, what is our policy? I can say: It is to wage war, by sea, land and air, with all our might and with all the strength that God can give us; to wage war against a monstrous tyranny, never surpassed in the dark, lamentable catalogue of human crime. That is our policy. You ask, what is our aim? I can answer in one word: It is victory, victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror, victory, however long and hard the road may be; for without victory, there is no survival.”

The Guardian review of Humankind was written by Jonathan Freedland who sums up the book in one more paragraph:

Stone by stone, Bregman breaks up the foundations that underpin much of our understanding of ourselves as callous, uncaring creatures hiding beneath a veneer of civilisation. That understanding has acted as a self-fulfilling prophecy, he says: if people expect the worst of each other, they’ll get it. He can cite the experiments that show even lab rats behave worse when their handlers assume they’ll behave badly. Our true nature is to be kind, caring and cooperative, he argues. We used to be like that – and we can be again.

Bregman is not denying the existence of self serving, wealth grabbing people in history, and in our time, who have tried to suck the life out of any society for their own gain. He is just arguing that we do not need to accept the idea that we are all beasts that need authoritarian control, and many of us who have suffered from the Hobbesian worldview can unlearn that behavior and chose to follow our more natural inclinations toward a better world where we work together to abolish disease, racism, and inequity, as we protect and preserve our planet.

A good physician who encounters a patient with chronic disease that is the result of many poor lifestyle choices works with the patient to learn a new approach to the choices of daily living. In the same way as a nation we could look at our current set of issues, and ask, “Does it have to be this way?” If there is anything positive to come from our collective misery, it would be to honestly answer that question. The next question might be, “Why is it this way?” Having answered those questions we can ask two more questions. “What must we do differently together?” and “What is my role in the effort to create a better society?” In that “better world” that is a more natural fit to our true nature, things would be vey different. We would defeat racism. Racism would be lumped with other superstitious fears that arise from ignorance. Embracing our true nature would enable us to equitably enjoy the abundance that we are capable of producing. In this new world post COVID-19 and racism everyone would benefit from the abundance of better health and opportunity. Bregman contends that we can all enjoy a better life, if we act on our natural instinct to care for one another.

We still have a long way to go in the struggle against COVID-19, the damage it has done to our economy, and the inequities in our society that are underlined by the declarative statement that Black Lives Matter. I offer Humankind: A Hopeful History to you as a good read that will give you reason to hope that if we listen to our natural instincts and respond to our “Better Angels” all this will eventually end in victory, as Churchill once promised his nation, if we are willing to have the courage and do the work necessary to follow our natural instincts of humankindness.