I saw aristocracy up close at Harvard Medical School. I quickly realized that some of my classmates were from families that were either power brokers in New York or Washington, or were the elite of American medicine. I discerned that I had been slotted into the class to fulfill some kind of mid sixties diversity formula. I provided regional and academic diversity being from a Southern state university. I now hear from Matthew Stewart that things have changed. Writing in the The Atlantic Magazine, he declares that “the aristocracy is dead.”

Stewart begins his article describing his family’s lost place in the American aristocracy and what has happened for him as a result:

I belonged to a new generation that believed in getting ahead through merit, and we defined merit in a straightforward way: test scores, grades, competitive résumé-stuffing, supremacy in board games and pickup basketball, and, of course, working for our keep…I came into many advantages by birth, but money was not among them.

On the basis of a job well done and the shot at the success that he has earned with his “merit,” he is now a member of America’s “new aristocracy,” and that is a good place for both him and his children. A place where he has it all and can be comfortable in jeans and a tee shirt. As he says:

I’ve joined a new aristocracy now, even if we still call ourselves meritocratic winners….To be sure, there is a lot to admire about my new group, which I’ll call—for reasons you’ll soon see—the 9.9 percent. We’ve dropped the old dress codes, put our faith in facts, and are (somewhat) more varied in skin tone and ethnicity. People like me, who have waning memories of life in an earlier ruling caste, are the exception, not the rule.

By any sociological or financial measure, it’s good to be us. It’s even better to be our kids. In our health, family life, friendship networks, and level of education, not to mention money, we are crushing the competition below. But we do have a blind spot, and it is located right in the center of the mirror: We seem to be the last to notice just how rapidly we’ve morphed, or what we’ve morphed into.

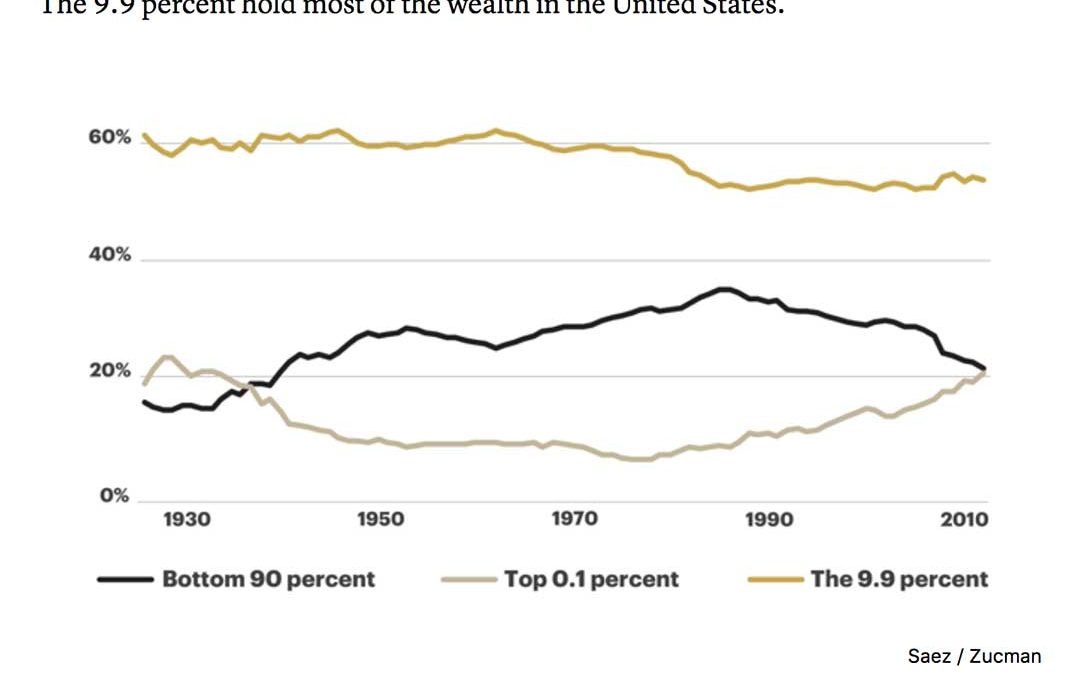

As you can see in the header, Stewart presents data that suggests that the expansion of capital and wealth by the richest 0.1 percent of Americans has come mostly at the expense of the lowest 90 percent of Americans who have about the same wealth that they did at the end of the sixties. The 9.9 percenters have lost a little to the ultra rich, but not much. It is still pretty good to be in the upper middle class or as Stewart defines, to be among the 9.9 percenters. Stewart’s analysis essentially seconds the motion that Steven Brill made in his recent Time Magazine article, “How Baby Boomers Broke America.” Brill proclaimed himself to be a part of the generation that succeeded through merit to the detriment of the country. The book that Brill published just after his Time article, Tailspin, covers the same territory and got a response from David Brooks in which he adds a resounding “amen” to the ideas of both Stewart and Brill.

We replaced a system based on birth with a fairer system based on talent. We opened up the universities and the workplace to Jews, women and minorities. University attendance surged, creating the most educated generation in history. We created a new boomer ethos, which was egalitarian (bluejeans everywhere!), socially conscious (recycling!) and deeply committed to ending bigotry.

You’d think all this would have made the U.S. the best governed nation in history. Instead, inequality rose. Faith in institutions plummeted. Social trust declined. The federal government became dysfunctional and society bitterly divided.

The chief accomplishment of the current educated elite is that it has produced a bipartisan revolt against itself, but we have retained the knack of passing on what we have to our children and neglecting many of the needs of the children of the 90 percent. The outcome is a level of inequality unrivaled since the early twentieth century.

If you have not yet generated a picture of who is in the 9.9 percent, Stewart gets descriptive. In dollars the threshold is a net worth of $1.2 million. It takes $10 million to knock on the door of the 0.1 percent. My guess is that the majority of physicians past mid career are safely over the threshold of the “meritocratic class.” This class is mostly white. 1.9 percent of the top “10th” of households are African American. 2.4 percent are Hispanic, and all other minorities including Asians are 8.8 percent, “….even though those groups together account for 35 percent of the total population.”

To bring it even closer to home.

We’re a well-behaved, flannel-suited crowd of lawyers, doctors, dentists, mid-level investment bankers, M.B.A.s with opaque job titles, and assorted other professionals—the kind of people you might invite to dinner. In fact, we’re so self-effacing, we deny our own existence. We keep insisting that we’re “middle class.”

Stewart then presents some disturbing statistics:

The Institute for Policy Studies calculated that, setting aside money invested in “durable goods” such as furniture and a family car, the median black family had net wealth of $1,700 in 2013, and the median Latino family had $2,000, compared with $116,800 for the median white family. A 2015 study in Boston found that the wealth of the median white family there was $247,500, while the wealth of the median African American family was $8. That is not a typo. That’s two grande cappuccinos. That and another 300,000 cups of coffee will get you into the 9.9 percent.

What is the practical consequence of these statistics in the context of the American ideal that the United States is a place where everybody has a chance to do well and to move up the economic ladder? Stewart provides evidence that debunks this pleasant fiction in the form of an economic concept referred to as the “intergenerational earnings elasticity,” or IGE, which measures how much of a child’s deviation from average income can be accounted for by the parents’ income.” It turns out that if your parents are poor it is more than likely that you will have the same experience or worse. If times get tough as they did in 2008, and continue to be for many people who were employed in manufacturing jobs that moved overseas or were replaced by automation, you are highly likely to not do as well as your parents.

The big advantage of the children of the 9.9 percent is that they have family resources. Their family probably has a home that has equity and can help finance an education to keep the merit process going or can allow for a false start or two, or perhaps help with a launch into business or a down payment on a home in a town with good schools for the kids. Stewart quotes an economist that points out that intergenerational economic mobility in America now is more like Chile than Japan or Germany. He then shows that this trend leading to less and less intergenerational economic upward mobility is a major cause of our accelerating economic inequality.

Like Brill, Stewart suggests that the winners in the merit game have figured out how to solidify their gains. Ironically the 9.9 percent has discovered that it is useful to be considered part of the “middle class.” He also points out the importance of social connections to maintain a family’s position in the new meritocracy that are not an option for those trapped below. Stewart then becomes somewhat accusatory and offers warnings:

It’s one of the delusions of our meritocratic class, however, to assume that if our actions are individually blameless, then the sum of our actions will be good for society…The fact of the matter is that we have silently and collectively opted for inequality, and this is what inequality does.

This is where Stewart begins to bring in the health related outcomes to the growing inequality that seems to arise in such a benign and meritorious way.

Obesity, diabetes, heart disease, kidney disease, and liver disease are all two to three times more common in individuals who have a family income of less than $35,000 than in those who have a family income greater than $100,000. Among low-educated, middle-aged whites, the death rate in the United States—alone in the developed world—increased in the first decade and a half of the 21st century. Driving the trend is the rapid growth in what the Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton call “deaths of despair”—suicides and alcohol- and drug-related deaths.

…We 9.9 percenters live in safer neighborhoods, go to better schools, have shorter commutes, receive higher-quality health care, and, when circumstances require, serve time in better prisons. We also have more friends—the kind of friends who will introduce us to new clients or line up great internships for our kids.

Stewart contends that the 9.9 percent not only know how to control wealth, education, and the professions, we also know how to control the output of government to our advantage. Many of the laws that have been written to look like a leg up for the lower middle class are a greater boon for the 9.9 percenters and their children. I flinched a little when I read I read Stewart’s analysis. Thomas Shapiro made many of the same points in Toxic Inequality, as did Matthew Desmond in his Pulitzer Prize winning book Eviction. Like Desmond, Stewart adds to the argument that your ZIP code may be more of a determinant of your life expectancy than your genetic code.

The outsized success of the 9.9 percenters has not gone unnoticed by the 90 percent, and the election of Donald Trump may be the most obvious manifestation of their resentment. Stewart wonders what other forms of retaliation will arise to threaten the 9.9 percent. Inequality breeds envy, envy begats resentment, and resentment spawns negative responses that create even wider divisions. The question that faces us who care about the health of the nation is how do we make advances toward the Triple Aim in a climate of resentment. Resentment also produces instability. As Stewart says:

The raging polarization of American political life is not the consequence of bad manners or a lack of mutual understanding. It is just the loud aftermath of escalating inequality…

Stewart suggests that we emulate the bright moment of America’s beginning when an upper middle class and aristocracy were willing to limit some of their gains to improve the experience of less affluent white men. Stewart’s analysis looks a lot like addressing the issues that are the social determinants of health.

In our world, now, we need to understand that access to the means of sustaining good health, the opportunity to learn from the wisdom accumulated in our culture, and the expectation that one may do so in a decent home and neighborhood are not privileges to be reserved for the few who have learned to game the system. They are rights that follow from the same source as those that an earlier generation called life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

He takes a shot at the medical profession and essentially suggests that it has been a higher priority for us to maintain our compensation than it has been to expand the profession enough to provide for the care of all of our citizens at a sustainable cost. Many of us are 9.9 percent winners. The deck was stacked for us as it is for our children, but things can change, and history says it will, unless we seek to offer something better that will work. I think that is what Don Berwick knew when he suggested a “third era of medicine” where we don’t focus so much on finance and what we are making, but rather focus on all of our neighbors with a renewed commitment to making sure that everyone gets what they need.