I am no medical historian, but I dare say that the history of medicine could be described as a “search for a better way.” Sometimes the search is cheered by the people and supported by entrepreneurs and governments desperate for solutions to threatening problems. That has been our recent experience with the mRNA vaccine technology that allowed the more efficient approach to vaccine production that will produce more than 200 million vaccinated Americans about a year and a half after COVID-19 entered our vocabulary.

Again, I will confess that I am not a medical historian but the closest thing to the miracle of the COVID vaccine in my memory or experience was the Salk vaccine. The March of Dimes was organized in 1938 as the National Foundation for the Prevention of Infantile Paralysis by President Roosevelt who was a victim of polio in 1921. After FDR’s death and the appearance of his profile on dimes, the organization became The March of Dimes.

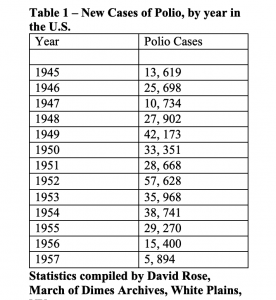

There was a severe epidemic of polio in 1949, as can be appreciated by examining the table below, and in response, the March of Dimes began to fund the research of a young University of Pittsburg researcher, Dr. Jonas Salk. Salk produced a vaccine composed of the “killed virus.” The vaccine contained the three common types of poliovirus that Salk “killed” with formalin. The first trial began with children at the Arsenal Elementary School in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on February 24, !954. Salk’s vaccine was licensed for use on April 12, 1955, after a trial with 1.8 million school children was completed. I think that I got my vaccination with the Salk vaccine at the Sanger Avenue Elementary school in the late spring of 1955 when I was in the fourth grade. The positive results were immediately obvious despite the huge error of some doses being contaminated with live poliovirus which is discussed below. In 1954, the year the trial began there were 38,741 polio cases in the country. In 1955, as we were getting vaccinated and despite the live virus error, there were 29, 270. In 1956 the number was down to 15,400 which probably still included some of those “vaccinated” with the live virus. In 1957 there were only 5,894 cases in America. In 2018 there were only 33 cases worldwide.

Polio was particularly fierce in the late forties and early fifties in Texas where I moved in January 1954. It was a “summertime” enteric virus associated with contaminated water which made our parents fearful of letting us go swimming. In 1954, I had classmates who were afflicted. When the vaccine was ready, I was delighted to get my “shot.” Not every child who was vaccinated in 1955 did well. One of the licensed manufacturers, Cutter Laboratories, a privately held family-owned company in California, produced a deficient vaccine that because of an error in production contained the live virus. It was a disaster. At least 220 000 people were infected with live poliovirus in Cutter’s vaccine (including 100 000 contacts of immunized children), 70 000 developed muscle weakness, 164 were severely paralyzed, and 10 died. Is there a relationship between that event and concerns about the safety of all vaccines?

We are definitely into a period of hope associated with the rapid mobilization of the distribution in this country, if not worldwide. Most of my family has been vaccinated either because of eligibility related to employment, the fact that they live in a ZIP code that has a large minority population, or their persistence in looking for “surplus vaccine” that rightfully is not discarded. My wife and I went through the “normal channels” here in New Hampshire and got our first Pfizer dose on March 5, and are scheduled to get our second shot this coming Friday. I have the same sense of relief that I enjoyed in 1955 when I knew that I was protected from polio and could go swimming.

Perhaps, there are insights for us to gain from the experience with the polio vaccine. Lesson number one is that we are a great nation that is capable of doing amazing things in a very short time. A short time in the fifties was about four years. A short time sixty-five years later was less than a year from the recognition that there was a problem in Wuhan, China until we had several effective vaccines.

A second lesson is that there is a wide spectrum of risk acceptance and justifiable fear among otherwise “normal” humans. My eager anticipation is going to be countered by real fear and concern from others. Some of the skeptics among us have fears that may have some historical justification. Some of those fears are associated with the real analysis that there have been some errors in the past, and there is always the possibility of future errors. I was interested in learning that there were racial “disparities,” injustices, and inequities associated with polio. It is both unbelievable but a fact that it was a commonly accepted fact in an era of “white” only medicine that Blacks were not susceptible to polio. The March of DImes established a research program at the Tuskeegee Institute in 1941, now infamous for the site of the immoral studies of the natural history of syphilis in Black Americans which began in 1932. As you might expect, the Warm Springs, Georgia created for the treatment of polio, where FDR spent much of his time was a “white only” facility. Is the fact that Black Americans are getting vaccinated as a smaller percentage of the population a function of distrust based on historical reality and/or continuing inequity?

I must admit that I do not understand but must accept that there are those who reject vaccines based on some other calculus like a distrust of science, political preference, or conspiracy theories about vaccines. I accept science because I have witnessed it working in measurable ways. I have told the story before of discovering “acres” of iron lungs in the basement of Boston’s Children’s Hospital while I was searching for my advisor’s office in the fall of 1967 just a dozen years after the hospital had been treating numerous children with polio. Somewhere in that same institution John Enders, Thomas Weller, and Frances Chapman had isolated the poliovirus for the first time. Without their work, Salk would not have had viruses to “kill” for his vaccine. Enders inherited a huge fortune and worked for a dollar a year. He was “the lead” scientist, but he was also known for giving others much of the credit for his work.

A third takeaway from the experience of the conquest of polio is that following a scientific breakthrough or game-changing event things stay changed. We reluctantly enter a new world. I ask myself why the Children’s Hospital hung onto dozens and dozens of iron lungs for more than a decade after they were needed? Did they expect that they would need them again?

Change is not easy for us even when there is a huge upside. There are many examples that have nothing to do with healthcare, and it often takes us a while to recognize that a transition has occurred. Television is a good example. One of my pet peeves is all of the medical ads that are repeated again and again during the “news hours” in the evenings. There are claims and disclaimers for a host of drugs that are rarely used before mid-life. It occurred to me that advertisers are targeting my demographic. They know that my children do not watch television news. Television’s nightly news with all the little human interests add ons and its ads is produced for older people. Gen X-ers, Millennials, and Gen Z-ers get the news they want via social media. Things have changed. They will never be the same again. It just takes a while for all of us who have bonded with the old way to move on to our reward.

In a slightly different way, healthcare is often slow to change. Atul Gawande wrote about “Slow Ideas” in a very insightful New Yorker article in 2013 entitled “Slow Ideas: Some innovations spread fast. How do you speed the ones that don’t?” Gawande compared the rapid acceptance of anesthesia with the very protracted introduction of antiseptic surgical techniques. His conclusion:

So what were the key differences? First, one combatted a visible and immediate problem (pain); the other combatted an invisible problem (germs) whose effects wouldn’t be manifest until well after the operation. Second, although both made life better for patients, only one made life better for doctors. Anesthesia changed surgery from a brutal, time-pressured assault on a shrieking patient to a quiet, considered procedure. Listerism, by contrast, required the operator to work in a shower of carbolic acid. Even low dilutions burned the surgeons’ hands. You can imagine why Lister’s crusade might have been a tough sell.

There is more than a little cynicism in Gawande’s sense that doctors rapidly adapted what they valued. Doctors are not the only agents that function out of self-interest and ignore what is better if the change requires major adaptations or the abandonment of what will be non-performing assets in the new normal. You need to look no further than the telephone wires along the sides of highways and ask who owns them and what irreplaceable benefit do they serve. Our children don’t watch the evening news and many don’t see the need to pay for a landline with its associated expense. I guess we might conclude from Gawande’s observations and ours that the new normal arrives quickly when there is an upside or compelling reason for everyone and at a much slower pace when there are assets to retire or a difficult learning curve to mount.

I was sitting in my underwear and a johnny recently at my dermatologist’s office awaiting the semiannual harvesting of the various skin tumors that my parents dealt me three-quarters of a century ago when they allowed me to run around almost naked in the Southern sunshine from the end of school in late May until it resumed again in early September. This exam revealed only one innocently appearing little basal cell on my lower leg along with my relatively stable patches of actinic keratoses on my face, ears, and arms. Biopsies were deemed not necessary. I just need to bathe daily in 5 fluorouracil before a follow-up in three months.

The office flow was a little slow so I had some time to think about my surroundings which you can see a little of in today’s header. Will exam rooms become telephone landlines and evening news of the new normal of the post-pandemic era? I don’t see them going away, but I also don’t see much need for all the ones we have.

To say that telehealth is here to stay does not say enough. Sooner or later I am sure that the Children’s Hospital cleared out all of its iron lungs. Perhaps one or two are in a museum somewhere. I think that I have a “Princess Phone” somewhere in the attic. It will take us a while to answer the question about exam rooms, and I should add hospital rooms. Few people want to occupy a hospital bed if there is an alternative, and fewer still want to waste half a day having an outpatient visit if the necessary contact or important exchange of information can occur virtually.

There are many questions to answer. We were long overdue for the shift to telehealth. If there was one good thing to come from the pandemic it has been to demonstrate that some things work really well in the virtual environment. One question that will face us as we become comfortable with the idea that the vaccines have worked and that the pandemic is fading in our collective rearview mirror will be how do we optimally use the ability to provide care and receive medical care virtually. I see virtual care used optimally as a way to reduce health care disparities, improve the health of individuals and the community, and reduce the cost of care.

Public education is showing some downside reality to the virtual classroom. What may evolve in healthcare could be similar to what evolves in education—a careful and thoughtful blend of the two. My suggestion is that we use the six domains of quality: patient experience, safety, efficiency, effectiveness, equity, and timeliness as a tool that will help us to decide what should be done virtually and what needs to return to the office and the hospital. The process will be fascinating to watch.

Over the last five years of my practice, while I was a CEO, all most all of my clinical contact occurred in shared medical appointments. I really enjoyed the experience. I found that patients loved the visits. I was convinced that for chronic disease management and for several other types of visits, the shared medical appointment was superior to the usual office visit. While I was sitting in my dermatologist’s office I had an idea. Would it not be great to do a virtual shared medical appointment? What could be a better example of, “There is always a better way!”?

I let the idea go for a few weeks until I started to write this letter. Before claiming the idea I decided that I should type “virtual shared medical appointment” into Google and see what bobbed to the surface. To my chagrin, my idea is already in the works. In January 2021, Kamalini Ramdas and Soumya Swaminathan writing from the World Health Organization’s (WHO) project on a Global Strategy on Digital Health published a paper in Nature Medicine entitled “Patients could share virtual medical appointments for better access to telemedicine.” The brief abstract reads:

Shared medical appointments, whereby patients with similar medical conditions consult their medical practitioner together, alleviate pressure on the health system and provide an instant support network for the patient. Why not make them virtual?

I guess the bottom line is that it is likely to always be true that there is a “better way.” We just need to be open to the work of adaptive change. Difficult times can provide the momentum that can overcome the resistance to looking for a better way. As the old saw says, “Necessity is the mother of invention.”