Since last week’s First Democratic Presidential Primary debates I keep thinking about Medicare for All versus Medicare for All Who Want It. I am sure there are many things about this complex conversation that I do not completely understand, and in that regard I think that I am no further off the mark than the candidates or most voters. In this post I hope to begin a discussion that will be ongoing through the long run-up to the election that will catalog what we all know for sure, what we don’t know for sure and speculate about, and what we know we don’t know. As Donald Rumsfeld said, what should really worry us is what we don’t know that we don’t know. He called them the unknown unknowns. I hope through the ongoing discussion that together we might understand that we must go far beyond universal coverage as our goal. I don’t think that all politicians understand that universal coverage is necessary for health, but insufficient alone as a change that will improve the health of the nation. I hope that I can advance the concept that if the Triple Aim is the goal, we must both have universal coverage and make progress against the disparities and inequities that are the foundational problems to what we call the social determinants of health. It is in this area beyond coverage that healthcare intersects with many of the other issues of the day like the Green New Deal and all of the issues of race, diversity, education, housing, infrastructure decline, immigration, and the complex issues of economic opportunity and economic inequality. You can’t be interested in improving the health of individuals and our communities and limit your focus to universal coverage.

Before I go further, I must share with you that two of the moments in the debates that surprised and delighted me most came from the most unusual candidate on the stage, Marianne Williamson. Her comments are worth reviewing because she pointed to the mindset that is required of any policy process that has a chance for success. Her campaign slogan is “Think. Love. Participate: Be part of the change that America needs.” During the portion of the debate when the questions were about healthcare she got a big round of applause when she said:

“Even if we’re just talking about the superficial fixes — ladies and gentlemen, we don’t have a health care system in the United States, we have a sickness care system in the United States. We just wait until someone gets sick and talk about who is going to pay for the treatment.”

If you think that was bold and profound in a concise way, you will love her 45 second final statement:

“Donald Trump is not going to be beaten just by insider politics talk. He’s not going to be beaten just somebody who has plans. He’s going to be beaten by somebody who has an idea what this man has done. This man has reached into the psyche of the American people and he has harnessed fear for political purposes. So, Mr. President, if you’re listening, I want you to hear me, please. You have harnessed fear for political purposes and only love can cast that out. So I, sir, I have a feeling you know what you’re doing. I’m going to harness love for political purposes. I will meet you on that field. And, sir, love will win,”

Back in 1967 during the “summer of love,” the Beatles told us that “All You Need Is Love.” The sentiment in their song was considered simplistic, but I think that John Lennon’s and Marianne Williamson’s embrace of love may hold the key to making progress toward the Triple Aim as well as real progress toward equality in our society which would reduce the socioeconomic gradient we see in health where our population health data suggests that your life expectancy is determined more by your zip code than your genetic code.

One of the great failures of the English language is its lack of flexibility and nuance when it comes to talking about the feelings that we lump together as “love.” Ministers and some academics point to classical Greek as having more flexibility since it has at least six different words that we translate as love: eros, philia, ludus, agape, pragma, and philautia. Agape, a selfless love that is extended to all people, be they strangers or close family, is a radical kind of love that our president gives little evidence of understanding or feeling. The Latin word for that same feeling is “caritas,” the origin of our English word, charity. The reference at the end of the link says that the Greeks recognized that there were two types of “self love.” In one form, narcissism, the focus is entirely on self as demonstrated by our usual meaning when we talk about narcissism. In the second kind of self love, a high regard for self is extended to all people. That sounds a little like agape to me.

It has been my experience that most clinicians and a majority of healthcare professionals who support practice are driven by their care and concern for the patient. When I say that, I recognize that there are some who appear to others only to care about science, their academic advancement, their financial well being, or the business issues of their institutions, but I am extending to them the benefit of the concept that buried under those more easily perceived interests there is a foundation of concern that is aligned with the principles of professionalism and our obligation to care about the people we serve. Almost all politicians claim that their primary purpose is to “work for the people.” In her recent book LEADERSHIP In Turbulent Times, Doris Kearns Goodwin identifies strong personal ambition and a desire for personal recognition as driving forces in Lincoln, Teddy Roosevelt, FDR, and LBJ, but shows how they managed their “narcissism” so that personal ambition was always secondary to the more powerful conscious recognition that their responsibility to the nation and its people came ahead of their own ambitions.

In his recent book A THOUSAND SMALL SANITIES:The Moral Adventure of Liberalism, Adam Gopnik, a New Yorker writer defends liberal thought, but also tries hard to understand the mindset of the “other side.” He rejects the authoritarian tendencies of far right conservatism and far left “illiberalism.” David Frum, the author of the New York Times review to which the link will take you, suggests that Gopnik is arguing that liberals and conservatives can both become so focused on their “rightness” that are vulnerable to using force to establish their principles. Love, or if that word doesn’t feel acceptable to you, “fellow feeling,” or just plain old respect for others who may hold an opinion that is different than your own, is a foundational necessity for any future healthcare policy that will gain the wide acceptance necessary to take root and prosper for the decades of increasing improvement that will be necessary. The ACA has taught us that healthcare is too complex to get it right on initial design. What we need is a process of continuous improvement and learning. We have tried to continuously improve Medicare and Medicaid since since they were created in 1965. Republicans and Democrats have offered and passed modifications of the original bills that over time have improved them. Indeed, the ACA can be viewed as another step in the attempt to improve Medicare and Medicaid.

Nothing would advance the cause of the Triple Aim more than for us to discover how to have a bipartisan healthcare process built on the shared interest of improving the health of the nation through universal access. It seems now that a healthcare discussion without healthcare being an issue in an election is improbable. Achieving the Triple Aim, much less the larger objective of decreasing the inequities that exist in our society enough to begin to improve the social determinants of health will remain distant goals until we can collective make a little more progress toward the objectives that Williamson advocates.

A nation divided within itself by fear and disrespectful treatment of anyone who does not agree with a single point of view is in danger of more than poor health. It is toying with becoming an authoritarian state. Likewise, if our collective narcissism is so great that we consistently make the needs of people in other nations and on other continents secondary to our own self interest we are risking much more than our role as leader of the free world, and as a beacon of hope to all people. It is also true that if “a better way” is rammed down the throats of the 40% of Americans that currently control a majority in the Senate and the Supreme Court, the likelihood of long term success is also small.

We have been trying to improve the inequities in our society for a very long time. The effort is obvious going back to before the Civil War and long before the progressive movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For at least a hundred years, there have been those among us who have dreamed of and worked hard for a more equitable distribution of the benefits of healthcare. In both areas we have made progress, and in both areas we have a long way to go. The tension that was palpable in the healthcare discussions in the Democratic Debates did not arise from disagreement about the objectives of improving the inequities between the 1% and the 99%, or more realistically the 10% and the 90%, or of the goal of universal healthcare access with sustainable costs and equity in services. The discussion was about how to continue to make progress toward those goals without suffering setbacks from either conceptual error, or effectively organized political resistance.

Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders stand tall and speak loudly that both issues, inequity in income and in healthcare, have gone on long enough and must stop as soon after January 20, 2021 as possible. They are tired of waiting, and point to those in fiscal and physical pain as justification for waiting no longer. They shout from their podiums that the disadvantaged which may be as much as 90% of the population, need relief now. Other candidates seem to have been traumatized by the experience of defending the ACA and losing other economic battles. They fear pushing too hard advancing a platform that will backfire and get the president reelected. Needless to say that the debates are further complicated by issues of race, sexual orientation, age, ethnicity, and social class. Ms. Williamson’s concept of love mitigates much of the affect that limits progress on the issues that are critical to us all.

I have long contended that Republicans have inflated to their advantage President Obama’s honest misstatement on several occasions in 2009, even before the ACA was law, that “if you like your health care plan, you’ll be able to keep it.”

Remarks at the American Medical Association, June 15, 2009: “I know that there are millions of Americans who are content with their health care coverage — they like their plan and, most importantly, they value their relationship with their doctor. They trust you. And that means that no matter how we reform health care, we will keep this promise to the American people: If you like your doctor, you will be able to keep your doctor, period. If you like your health care plan, you’ll be able to keep your health care plan, period. No one will take it away, no matter what.”

The clarification, that came much too late, was that if your plan conforms to, or is upgraded to conform to the specifications of the ACA, then you can keep it. The ACA was an attempt to do many, many things, some sequenced, some immediate. It was a very bold piece of legislation that attempted to make a meaningful difference. It was created by a methodology that tried to incorporate what was learned from the failures of the Clinton plan of 1993. It was meant to be a bipartisan process, but in the end, after forcing compromises in the committees that created the plan, Republicans voted against it, and began the harassment that has persisted to this day and is well reviewed in a recent Perspectives article in the New England Journal by Johnathan Oberlander, “Sitting in Limbo–Obamacare under Divided Government.” It is the opinion of many, including me, that the removal of the “public option” from the final version of the ACA greatly undermined the objective of creating a market that would have a chance to control costs.

It has not been much discussed, but the reason that the ACA does not cover everyone is that people can choose not to participate. The mandate was a weak inducement for participation, but the major objection that I always had was that even as it was being written, and going back to the 2008 presidential campaign, it was known that there would be tens of millions of people who would not be covered. Had the Medicaid expansion for those under 137% of poverty been accepted by all states, the bulk of the uncovered would have been middle class people who chose not to accept the graduated government subsidizes for those up to 400% of poverty, and many who were above the 400% level who would get no subsidy, and would elect to pay the penalty for not complying with the mandate. Indeed, some of the new money to finance the subsidies required to support the program were budgeted from the funds that were anticipated from the mandate penalty!

Vox gives us a clear report about why Elizabeth Warren supports Medicare For All:

Warren, a co-sponsor of Sanders’s single-payer bill, raised her hand in response to Holt’s question and confirmed she supports ending private insurance.

“Look at the business model of an insurance company. It’s to bring in as many dollars as they can in premiums and to pay out as few dollars as possible for your health care,” she said at Wednesday’s debate. “That leaves families with rising premiums, rising co-pays, and fighting with insurance companies to try to get the health care that their doctors say that they and their children need.

“Medicare-for-all solves that problem,” she continued. “There are a lot of politicians who say, ‘Oh, it’s just not possible, we just can’t do it,’ have a lot of political reasons for this. What they’re really telling you is they just won’t fight for it. Well, health care is a basic human right, and I will fight for basic human rights.”

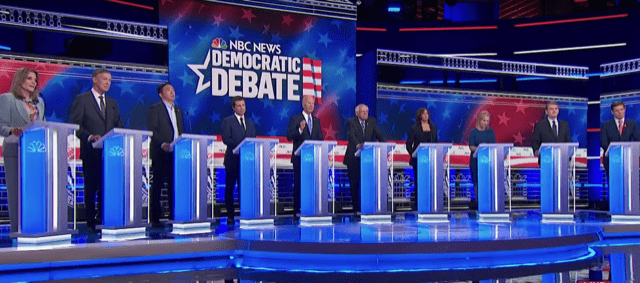

On both nights of the debates the candidates were asked to raise their hand in they supported Medicare For All which would eventually mean that no one would be covered by private insurance. Sanders and Warren both quickly raised their hands. Two other candidates responded to the request and raised their hands, Bill di Blasio, and Kamala Harris. Harris backed off overnight and announced the next day that she misunderstood the question. When each individual explained their position, the common explanation was that they wanted people to have the choice of keeping private insurance if they wanted it. The shift in opinion from a majority of Democratic candidates favoring Medicare for All to something less is the political reality of the fact that it is becoming clear that the public’s enthusiasm dims quickly when they hear about taxes going up and the loss of their own commercial insurance. I also think the candidates have not forgotten the price that Obama paid with his failed promise that if you like your insurance you can keep it.

I love the cynical reality that in our new world of the Internet that “free is not cheap enough.” Bernie Sanders tries hard to explain how “free healthcare for all” will be financed so that free is true for the very poorest among us and most of us end up paying less, and have less future uncertainty than we do now. In any good strategic discussion we soon come to realize that a concept of “perfect” remains the goal even as we set our objective for the next time around on a lesser goal. It is becoming clear to me that universal coverage reducing the number of uninsured, and reducing the cost of insurance for all of us, are not the same goals. It is also clear that until we all adopt a little of what Marianne Williamson is offering, progress toward any objective will be slow, and we will continue to operate under an increasing risk of authoritarian solutions.