In healthcare there is disappointing truth in the old saw, “The more things change, the more they remain the same.” It is paradoxically true that things are changing all the time. I observe that it is often true that in reference to a particular subject or problem what we really mean is that we are not closing a persistent gap. Poverty is a good example. A disturbing percentage of the population remains in poverty despite the billions of dollars we invest each year in public programs and private charitable activities that we hope might mitigate the problem for some individuals, if not for all, who live below the artificial dividing lines like 100% of poverty or 200% poverty that define access to support that we create between enough and not enough.

Healthcare, or if you prefer, our search for how to have healthier individuals and healthier communities, offer us many examples of problems that persist despite decades of effort to mitigate them. More than a decade ago I found treasure when I happened on the transcript of a speech that Dr. Robert Ebert, Dean of Harvard Medical School, gave in October 1967. The speech was given at Simmons College a few weeks after I had matriculated at his medical school. If you have been reading these notes for a few years you are aware of my fascination with the paper. It was like finding a time capsule. The speech was a window into the concerns of one of the most important medical educators and innovator of the day, and it creates a reference point that helps us gain perspective on our progress.

On the personal level, much of my interest in the speech arose from the realization that Dr. Ebert was operationalizing changes in medical education and practice that would have a profound effect on me. Dr. Ebert was thinking, writing, and speaking in the exciting time when we were just beginning to experience how Medicare and Medicaid would forever alter healthcare finance and care delivery. I believe that the speech has continuing benefit as a historical reference point as we contemplate changes in public support to healthcare that may represent even greater change.

In his speech Dr Ebert talked about the inadequate medical education we were giving young doctors. Much of his criticism was directed at medical schools and hospitals. He envisioned the move of more and more care to the ambulatory environment. He could see an expansion of the types of medical professionals. He could see a change in the role of physicians and nurses. Long before we talked about continuous improvement science in healthcare he was trying to apply the intellectual tools that he had developed in his bench research to the social problems that complicated healthcare delivery. He realized that there were “systems” problems that needed to be addressed long before most of us thought of “systems” in healthcare in ways other than the cardiovascular system or the digestive system.

After his analysis of medical education and the dysfunctions of the hospital and specialty medicine he turned his attention to what he called “The Distribution of Medical Care.” His greatest concerns in this category were the problems of care delivery to rural communities and the urban poor. He said:

Closely linked to the evolution of the modern hospital is the problem of the distribution of medical care. There are two groups who have suffered from the changing pattern of medical practice: the rural population and the urban population occupying the central city. Both groups present special problems, and both require new approaches to solutions. Most of you are familiar with the problem of the rural community. Here the general practitioner is the mainstay of the medical care system, but as he grows older he is not being replaced. Community after community attempts to recruit new family physicians only to find that young physicians do not wish to practice alone in a small town. The reasons are not hard to find. Most young physicians specialize and are unwilling to practice alone; they are more and more dependent upon the well-equipped modern hospital..Once again, curiously little imagination has been exercised in seeking solutions to this problem. In an age of modern transportation, when the evacuation of wounded from the jungle by helicopter is routine, it should not be too difficult to plan the care for rural communities. It would take a different kind of organization of physicians, however, and would require a kind of teamwork with other members of the health professions which physicians have been reluctant to provide except within the walls of the hospital…

Problems staffing rural healthcare persist today even though some of the innovations that Dr. Ebert offered as solutions have been implemented. Helicopters do take acutely ill and injured patients from rural hospitals to tertiary centers of care. Dr. Ebert saw more than the need to transport patients to academic medical centers. He foresaw team based care with each member having a redefined role that ensured the efficiency of working at the “top of their license.”

The provision of medical care in the rural community and in the central city will require a different kind of organization of medical resources than has existed in the past. The physician must learn to work more closely with social workers, nurses, visiting nurses, in fact all of the members of the health professions. There must be a sensible division of labor so that the physician performs those services which only he can do, and other duties are delegated to appropriate members of the health team. To a degree this has already been accomplished within the hospital, but team effort must be extended to provide care at all levels. This is not an easy problem for it will be necessary to make the most efficient use of expensive manpower and still maintain the personal nature of medical care. I believe this can be done but it will take innovation and will require of the physician a new kind of responsible social action. Care for the chronically ill and for the elderly, who so often suffer from chronic disease, is a particular case in point. Chronic illness is increasingly common and it cannot be handled effectively if it is thought of as an exclusively medical problem. The social, emotional and economic impacts of chronic disease must be understood and intelligently dealt with. Here the physician must share the responsibility with others who have special skills to offer.

All of those changes have now been implemented along with his innovative idea that we should use helicopters to bring patients from the rural environment to the services they might need in academic medical centers. As a member of the board of a rural health system, I know that in 2019 we have implemented all of the suggestions that Dr. Ebert made in 1967, but our most active system problem continues to be the difficult task of attracting doctors, nurses and other talented healthcare professionals to the small towns, villages, and rural environment that the system serves. Large urban areas like Syracuse, Pittsburg, Philadelphia, and Rochester are several hours away by car, and ironically even further in time by commercial air travel. We are challenged to sell the bucolic life to young health professionals who want city amenities. Yes, things have changed, but the problems persist, and there are now new challenges in “flyover” America where chronic disease, increasing mental health issues, and substance abuse are growing concerns.

I am absolutely sure that universal coverage that makes healthcare a right for every American, and not a privilege for the more affluent 85%, is necessary to improve our collective future. I am also certain that universal coverage will be insufficient to solve the problems of our rural communities. The healthcare problems of rural America, and the issues that complicate the cost and delivery of healthcare in urban America are very different. The principles of population health are critical in both environments, but I believe they are even more essential in the evolution of strategies for rural America.

Rural hospitals are failing at a disturbing rate, as was presented in a recent CBS presentation. If you watch the program you will realize that the issues are similar but different from town to town, but the solutions often lie beyond what is available locally. One obvious solution is to make each little town the member of a larger system. Systems of care are composed of connected members that are much like a family. High functioning families share, and they use their collective resources to help each other. In a highly functioning family each member receives the support that their needs require. These days good systems do a needs assessment for each of their communities as part of their strategic attempts to solve the problems that challenge them as a system.

I live in a little town with a very well appointed critical access hospital that I have presented in these notes before. Our hospital is affiliated with the Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical System, and like Dr. Ebert suggested over 50 years ago, we benefit from both helicopter and EMR connections to Dartmouth. Unlike Massachusetts, there is only one academic medical center within a hundred miles, so “market competition” as a vector for improvement is unrealistic. I am part of an eclectic group of citizens that is concerned about how to help members of our our community who are struggling. We decided to ask for the needs assessment that our hospital had done with Dartmouth Hitchcock. I was delighted to see the quality of the study, and not surprised by the information. I am eager for you to look at the report if you have never studied a needs assessment. Just click on the link. It won’t take long, and it might encourage you to ask for similar information wherever you live or work. In case you do not have the time or interest, just keep reading for my take on the highlights.

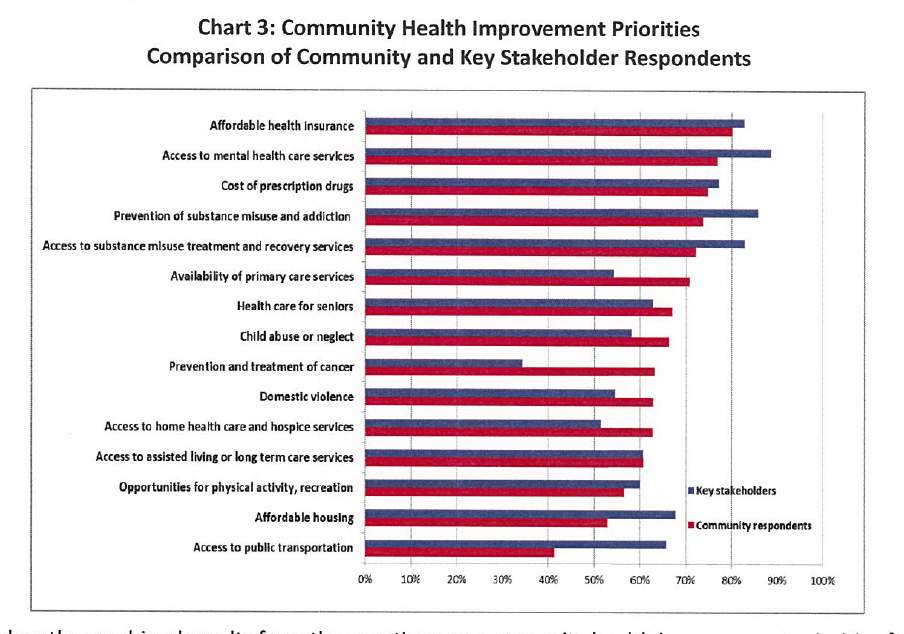

Our hospital serves 15 towns with a combined population of 33,000. There is a significant variation in income in the region from a median household income of $51,029 to $94, 583. The average income is $67,441. The poorest and largest community has 29.5% of families living under 200% of poverty. The biggest problems as reflected by opinion surveys and data acquired from consumers and stakeholders can be seen in the header for this note. They are affordable health insurance, access to mental health services, cost of prescription drugs, and substance misuse prevention, treatment, and recovery. Compared to the last study done in 2015 child abuse or neglect, and domestic violence have now moved up as higher priorities. Other new priorities are prevention and treatment of cancer and access to home health care and hospice services.

As you can see, both providers and consumers are aware of their need for mental health support. 38% of patients complained that the waiting time for an appointment was too long. 37% said that the service they needed was not available. 29% said that they could not pay for care whether they were covered or not. Medicaid recipients have a different experience than other patients when seeking mental health services. 43.4% of Medicaid recipients had trouble getting mental health services compared with 31. 6% of other patients. Do we have a two tiered system of care?

The beauty of the community assessment is that it allows assessment of progress. Teenage pregnancy rates have been cut in half since the assessment in 2015. One wonders what program caused the change. The community assessment is a picture of “what is” and the feelings of community members and “stakeholders.” It is not a plan, but it is essential to any effective plan, and perhaps it can be a tool to direct the distribution of scarce resources or a guide to program development. How can we address the unique issues of individual rural communities without the focus on community issues that needs assessments provide? How we can improve the health issues of rural America without more robust support and commitment from federal programs?