I was delighted to see another overview article of our COVID-19 experience by Ed Jong in the September issue of The Atlantic. In my opinion Jong has written an impressive series of articles about the pandemic. You might have noticed that I have quoted from his work frequently. The latest article is entitled “How the Pandemic Defeated America: A virus has brought the world’s most powerful country to its knees.” Perhaps you are tired of reading about the pandemic, but everything in the future will be affected by two realities that we can not ignore: the pandemic and the election. The two issues are inseparably linked, and no one knows for sure what will happen with either one. The virus continues to surprise us, and has consistently proven that anyone who thinks they know what will happen next is wrong. What will happen in the election is equally unpredictable for several reasons.

- The electoral college allows the selection of a president who wins a minority of the popular vote.

- The pandemic will make it impossible to have a “normal” election.

- The current president is capable of all the manipulative opportunities of an incumbent who consistently violates all the norms and precedents of his office.

- It is impossible to know the extent to which the Attorney General will function as the president’s “consigliere” rather than the nation’s highest law enforcement official. On several occasions, most notably, his distortion of the Mueller report and his willful use of federal agents under his control, he has chosen the best interest of his “boss” over his responsibilities to his office and the people.

- A fair election, or any election, threatens the president’s enablers in the Senate. They have already demonstrated that their fear of what he can do to them through his base can blind them to the constitutional responsibilities of their office.

- The president has already begun to undermine the election with claims of potential voter fraud, and attacks on voting by mail and the Post Office. The Brennan Center for Justice has published a warning entitled “Dirty Tricks: 9 Falsehoods that Could Undermine the 2020 Election.”

Our future is likely to remain uncertain long after election day for the same two reasons, the virus and the election. Jong’s article is an indictment of the president’s incompetence. He begins:

How did it come to this? A virus a thousand times smaller than a dust mote has humbled and humiliated the planet’s most powerful nation. America has failed to protect its people, leaving them with illness and financial ruin. It has lost its status as a global leader. It has careened between inaction and ineptitude. The breadth and magnitude of its errors are difficult, in the moment, to truly fathom.

Jong builds his argument with a withering description of our inaction and ineptitude:

Despite ample warning, the U.S. squandered every possible opportunity to control the coronavirus. And despite its considerable advantages—immense resources, biomedical might, scientific expertise—it floundered. While countries as different as South Korea, Thailand, Iceland, Slovakia, and Australia acted decisively to bend the curve of infections downward, the U.S. achieved merely a plateau in the spring, which changed to an appalling upward slope in the summer. “The U.S. fundamentally failed in ways that were worse than I ever could have imagined,” Julia Marcus, an infectious-disease epidemiologist at Harvard Medical School, told me.

Jong contends that all that we have experienced was “predictable and preventable.” His list of our failures are:

- A sluggish response by a government denuded of expertise allowed the coronavirus to gain a foothold.

- Chronic underfunding of public health neutered the nation’s ability to prevent the pathogen’s spread.

- A bloated, inefficient health-care system left hospitals ill-prepared for the ensuing wave of sickness.

- Racist policies that have endured since the days of colonization and slavery left Indigenous and Black Americans especially vulnerable to COVID‑19.

- The decades-long process of shredding the nation’s social safety net forced millions of essential workers in low-paying jobs to risk their life for their livelihood.

- The same social-media platforms that sowed partisanship and misinformation during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in Africa and the 2016 U.S. election became vectors for conspiracy theories during the 2020 pandemic.

He points out that it was well known throughout the government, the press, academia, and business that we were vulnerable to a devastating pandemic. Jong had written an article in 2018 about our vulnerability entitled “The Next Plague Is Coming. Is America Ready?: The epidemics of the early 21st century revealed a world unprepared, even as the risks continue to multiply. Much worse is coming. President Obama’s administration documented our vulnerability and had begun to develop strategies that were passed to President Trump who discarded them. We all know of Bill Gates’ famous Ted Talk in 2014 describing the urgency of preparing for the pandemic that was certainly coming. I reviewed this history on March 20 in these notes, in a post entitled “There Is Evidence That We Deserved A Better Effort.”

The president consistently blames China for the virus when the issue is not that there is a virus or its origin, but that he failed to manage an adequate response to the virus despite having control over immense resources, and the ability to have called for even more action in the defense of the nation’s health and its economy. He has consistently had the same three themes in the presentation of his own defense.

1.The Chinese are at fault, and the WHO covered it up.

2. The virus isn’t that bad and will be gone soon. You can protect yourself with hydroxychloroquine in the interim.

3. His actions have been “perfect,” and have saved lives. Others, especially “experts” have all made egregious errors.

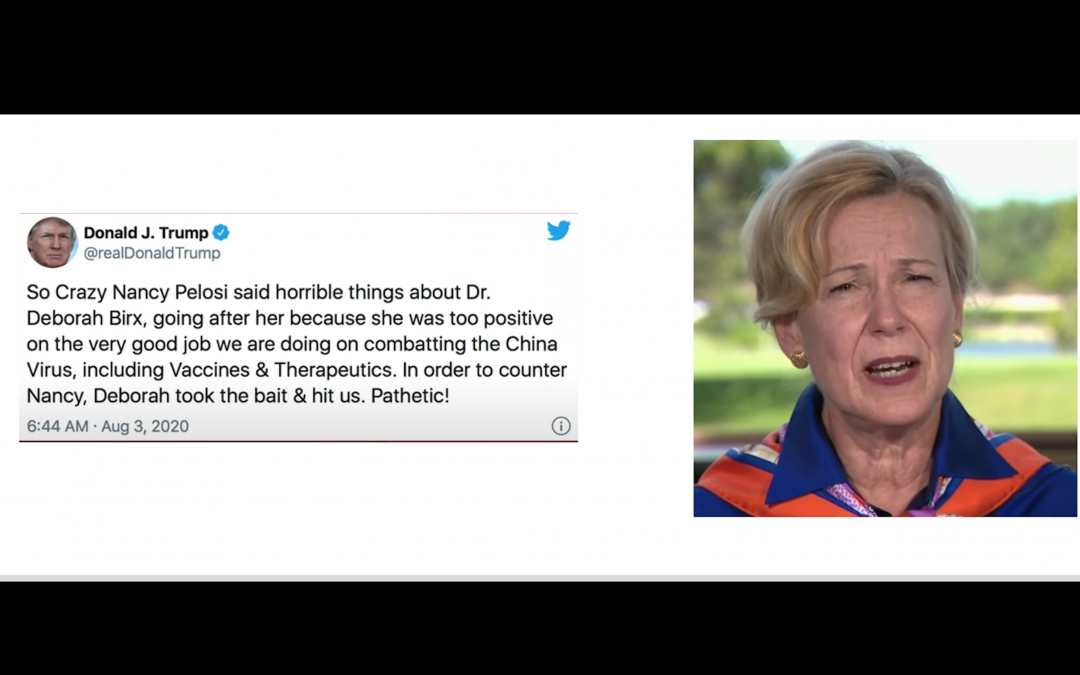

More despicable than his blaming the Chinese for the virus’ existence or down playing the danger of the virus while episodically exalting hydroxychloroquine is his strategy of blaming others for the failure of our inadequate response. He would probably consider Harry Truman’s concept of “the buck stops here” as the attitude of a “loser.” He has a rotating list of “losers” that he blames that includes the WHO, our governors, Dr. Fauci, the CDC, and even Alex Azar, his Secretary of Health and Human Services. As today’s header suggests, this week, Dr. Birx has become the latest target of his effective process of undermining confidence in others with the hope that it may exonerate him in the eyes of his faithful base.

In late June, Greg Sargent of the Washington Post wrote a column that begins with a long list of people and organizations that the president was trying to blame for his failures:

The article was written to add the CDC as the latest focus of the president’s blame game. Sargent quotes Politico:

Politically, Trump aides have also been looking for a person or entity outside of China to blame for the coronavirus response and have grown furious with the CDC, its public health guidance and its actions on testing, making it a prime target. But some wonder whether the wonky-sounding CDC, which the administration directly oversees, could be an effective fall guy on top of Trump’s efforts to blame the World Health Organization.

“WHO is an easy one,” said one former administration official. “It is foreign body in Switzerland. CDC will be tough to create a bogeyman around for the average voter.”

Sargent then says:

But Trump was far more of a contributor to the CDC’s failures than a victim of them. As a deep Times investigation concluded, the fact that Trump “wished away the pandemic” and tended to “dismiss findings from scientists” helped saddle the agency with “unprecedented challenges.”

We should return to Jong’s Atlantic article, not to add more evidence to the contention that President Trump failed in his responsibility to protect the country, but to shift our focus to what we should do now as we look around at the damage that has been done and is continuing. The real reason to examine our failures is to prepare for what’s to come, and to give up any idea of returning to the “normal” that made us road kill for the double challenge of the virus and an inept president who has always had Too Much, and Never Enough.

Jong’s continuing analysis is a closer look at what has gone wrong, and the ongoing concerns that flow from that analysis. As usual, I exercise some “editorial license” by bolding what I want you to notice.

Despite its epochal effects, COVID‑19 is merely a harbinger of worse plagues to come. The U.S. cannot prepare for these inevitable crises if it returns to normal, as many of its people ache to do. Normal led to this. Normal was a world ever more prone to a pandemic but ever less ready for one. To avert another catastrophe, the U.S. needs to grapple with all the ways normal failed us. It needs a full accounting of every recent misstep and foundational sin, every unattended weakness and unheeded warning, every festering wound and reopened scar.

Jong explains that we can’t blame it all on President Trump. Trump is responsible for much of what has happened here after the virus arrived, and he has failed to effectively use the power of the American presidency to assist other nations in their efforts to control the virus, but the emergence of the virus is the product of decades of collective action for which many of us share responsibility. “Modern life” has made us a setup for this and future viruses. Jong takes us on an in-depth review of many concerns like world travel and energy efficient buildings that make sense in one context, but contributed to the spread of the virus. Most of us have wanted more and never have felt we had enough, and the sum of our collective self serving strategies has devastated our environment and punched huge holes in our social safety net.

Water running along a pavement will readily seep into every crack; so, too, did the unchecked coronavirus seep into every fault line in the modern world. Consider our buildings. In response to the global energy crisis of the 1970s, architects made structures more energy-efficient by sealing them off from outdoor air, reducing ventilation rates. Pollutants and pathogens built up indoors, “ushering in the era of ‘sick buildings,’ ” says Joseph Allen, who studies environmental health at Harvard’s T. H. Chan School of Public Health. Energy efficiency is a pillar of modern climate policy, but there are ways to achieve it without sacrificing well-being. “We lost our way over the years and stopped designing buildings for people,” Allen says.

…One study showed that the odds of catching the virus from an infected person are roughly 19 times higher indoors than in open air. Shielded from the elements and among crowds clustered in prolonged proximity, the coronavirus ran rampant in the conference rooms of a Boston hotel, the cabins of the Diamond Princess cruise ship, and a church hall in Washington State where a choir practiced for just a few hours.

...The hardest-hit buildings were those that had been jammed with people for decades: prisons…Other densely packed facilities were also besieged. America’s nursing homes and long-term-care facilities house less than 1 percent of its people, but as of mid-June, they accounted for 40 percent of its coronavirus deaths.

I learned long ago that when faced with a complex problem, a good starting place to begin looking for a solution, is to ask, “What part of the problem am I/we.” Trump appeals to many of his base because he legitimizes many of their biases and desired behaviors. Even the most community centered individual is fatigued from efforts to social distance and wear a mask. If your president is modeling a narcissistic behavior and shares many of your frustrations, it feels OK to join him as part of the problem. We share some of the blame for our current pain with our leadership.

Just changing presidents will not protect us from continuation of this pandemic or help us avoid future events. If we review Jong’s list of “pre existing conditions” that compromised our response to the virus, we discover that indeed part of the problem is our healthcare system.

A bloated, inefficient health-care system left hospitals ill-prepared for the ensuing wave of sickness.

The part of the Problem that is our healthcare system was nicely presented by Jong in a quote from a frustrated healthcare executive who describes the misdirection of our efforts in healthcare, especially our discounting of the importance of public health.

America’s neglect of nursing homes and prisons, its sick buildings, and its botched deployment of tests are all indicative of its problematic attitude toward health: “Get hospitals ready and wait for sick people to show,” as Sheila Davis, the CEO of the nonprofit Partners in Health, puts it. “Especially in the beginning, we catered our entire [COVID‑19] response to the 20 percent of people who required hospitalization, rather than preventing transmission in the community.” The latter is the job of the public-health system, which prevents sickness in populations instead of merely treating it in individuals. That system pairs uneasily with a national temperament that views health as a matter of personal responsibility rather than a collective good.

Bingo! How different would our response to the virus have been if, and it is a very big if that has a huge message for the future, we saw the promotion of health for everyone as a collective responsibility. The great physician and advocate for continuous improvement, Paul Bataldan of Dartmouth, has reminded us frequently that “Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.” The results we see as the hospitalizations and death rates from COVID-19 climb, are in large part attributable a system that has designed itself through decades of seeking profit from healthcare delivery while the public clamored for lower taxes, and the budgets for public health were slashed to provide a few shekels of extra money to reduce the burden on taxpayers of providing everyone with a healthy environment, and personal access to care. I could argue that the same philosophy has reduced our investments in education, including medical education, housing, job training, public transportation, infrastructure including roads, bridges, our electrical grid, and the new highway of commerce, the Internet. Ironically, those who would save taxes by reducing funding for activities that improve the health and the quality of life for everyone, are delighted to inflate the budgets for law enforcement and the military.

Jong delivered a host of facts that documented our failures in public health funding that led to 55,000 jobs in public health lost since 2009 in the ramp up to the pandemic. As experts warned that we would have a deadly pandemic sooner or later, we went out of the way to make sure that we were not ready. Public budgets were cut when we should have been investing. That’s what happens when there is always a desire for more, and what we personally have is never enough. David Brooks has written that between the middle of the last century and now the pendulum has swung from the interests of the extended family and the community to the concerns of the individual. Some refer to the “Me Generation” of the seventies. Baby boomers still hold the power, and there is some justified anger in “OK Boomer.” No matter what your position or generation it seems clear from an analysis of the deficiencies in healthcare that the virus demonstrates that we have a problem that hurts now and extends far into our collective future.

“As public health did its job, it became a target” of budget cuts, says Lori Freeman, the CEO of the National Association of County and City Health Officials.

Today, the U.S. spends just 2.5 percent of its gigantic health-care budget on public health. Underfunded health departments were already struggling to deal with opioid addiction, climbing obesity rates, contaminated water, and easily preventable diseases. Last year saw the most measles cases since 1992. In 2018, the U.S. had 115,000 cases of syphilis and 580,000 cases of gonorrhea—numbers not seen in almost three decades. It has 1.7 million cases of chlamydia, the highest number ever recorded.

Since the last recession, in 2009, chronically strapped local health departments have lost 55,000 jobs—a quarter of their workforce. When COVID‑19 arrived, the economic downturn forced overstretched departments to furlough more employees. When states needed battalions of public-health workers to find infected people and trace their contacts, they had to hire and train people from scratch.

Jong’s article is extensive. In words alone he devotes about the same number to describing the failures of healthcare in the pandemic that he uses to call out the president. I will leave the rest to you to read, but he sums up his indictment of our system of care with a statement that is hard to deny:

In the middle of the greatest health and economic crises in generations, millions of Americans have found themselves impoverished and disconnected from medical care.

What will happen between now and the election remains anyone’s guess. Few people appreciated our jeopardy before the election in 2016 or the outbreak of COVID-19. The only certainty that I can maintain is that if we do not have a new president in January of 2021 things will get even worse. There are more potential viruses and other unexpected pitfalls ahead, and we have not yet recovered from this one. Close to the end of the article Jong beautiful describes the failures of this president and you can imagine for yourself how those failures will continue into a second term:

No one should be shocked that a liar who has made almost 20,000 false or misleading claims during his presidency would lie about whether the U.S. had the pandemic under control; that a racist who gave birth to birtherism would do little to stop a virus that was disproportionately killing Black people; that a xenophobe who presided over the creation of new immigrant-detention centers would order meatpacking plants with a substantial immigrant workforce to remain open; that a cruel man devoid of empathy would fail to calm fearful citizens; that a narcissist who cannot stand to be upstaged would refuse to tap the deep well of experts at his disposal; that a scion of nepotism would hand control of a shadow coronavirus task force to his unqualified son-in-law; that an armchair polymath would claim to have a “natural ability” at medicine and display it by wondering out loud about the curative potential of injecting disinfectant; that an egotist incapable of admitting failure would try to distract from his greatest one by blaming China, defunding the WHO, and promoting miracle drugs; or that a president who has been shielded by his party from any shred of accountability would say, when asked about the lack of testing, “I don’t take any responsibility at all.”

Perhaps the most starting idea Jong offers to us to consider as we move through the three months to our uncertain election is:

COVID‐19 is an assault on America’s body, and a referendum on the ideas that animate its culture.

He follows that thought with his closing words that should call each of us to consider how we face the future in healthcare and the entirety of our future existence:

Recovery is possible, but it demands radical introspection. America would be wise to help reverse the ruination of the natural world, a process that continues to shunt animal diseases into human bodies. It should strive to prevent sickness instead of profiting from it. It should build a health-care system that prizes resilience over brittle efficiency, and an information system that favors light over heat. It should rebuild its international alliances, its social safety net, and its trust in empiricism. It should address the health inequities that flow from its history. Not least, it should elect leaders with sound judgment, high character, and respect for science, logic, and reason.

I have my fingers crossed and my anxieties are high. I don’t know if things will be better if we have a new president in 2021. Building back better will require a lot of change. I do know that an increasingly dystopian world is the certain outcome of re electing this president. Before COVID and this president’s manifest failures of leadership, having achieved my 75th birthday, my life expectancy had increased to about 87. Now I am not so sure. But it’s not really about me, it is about the continuing experience and expectations of my children and grandchildren, and far beyond them. The wisdom that “if it can’t go on forever it won’t” does not tell us anything other than that change is inevitable. Positive change in our collective future will take collective work and shared investment that can’t happen under a leader who has always had too much that was never enough. Positive change is up to us. After we consider what part of the problem we own, then we can consider our own role in the changes we want to see. (My apologies to Gandhi.)

Is Jeffrey Epstein’s Island for sale?