I was apprehensive when I sent out last Friday’s “Healthcare Musings.” The main section of the letter was entitled “We Must Address Poverty and the Social Determinants of Health.” I was concerned that some readers might not consider discussing poverty as an appropriate subject, even if it was connected to the “social determinants of health.” My objective was to make the case that because so many patients live in poverty, and we now have objective evidence that poverty is a risk factor for many diseases and results in measurable reductions in life expectancy, clinicians have an individual professional responsibility to be involved in efforts to eradicate poverty. I tried to make the case that our efforts must go beyond places where we do most of our work: the exam rooms in our offices and the hospitals we use.

I am not sure when I first came across the idea that some of the stress of practice that we call “burnout” arises from the frustration and anger that is precipitated by the request that clinicians deal with the social issues that complicate the medical problems that are derivatives of poverty. I have heard clinicians logically argue that it is hard for them to see the benefit of the time and resources from this medicalization of social issues since the problems rarely seem to improve. They argue that their office is the wrong place, a medical appointment is the wrong time, a physician or nurse is the wrong professional, and the resources in the office and hospital are usually the wrong tools to apply to the problems in health that poverty creates.

I was not surprised when a very loyal “Interested Reader” wrote me to say:

“I continue to contemplate a term that you quote in your piece, the “medicalization of poverty”, which I think reflects some defensiveness on the part of the clinical world, but may also mean that addressing social determinants is growing in visibility and acceptance.”

I felt that it was important to respond, and I also asked the reader if I could share the conversation with you. My note back to him was:

Joe,

I am very thankful for this note. It will be the origin of my post for tomorrow. If you Google the term “medicalization of poverty” you will find a lot to read. I think that the term has not settled into a universally accepted definition. I am not exactly sure when it entered my own consciousness, nor can I honestly say that I always use it in exactly the same way…

In this post I was using the term in the most negative of ways. I was “channeling” the frustration of practicing physicians who are right for the wrong reason. I have heard doctors who want to continue to practice as they have always practiced point out how frustrating and impossible it is to try to deal with the “disease” of poverty during an appointment scheduled for 15 minutes.

They realize that it is an impossible task and therefore argue that those problems go to more appropriate sources of redress. That sounds good until you admit that no such source exists. The problems of poverty are hard to address even at a population level. Individuals can be helped in a preventative way with programs like you are trying to start, or by outreach programs that provide skills that enable individuals to have an economic break like Per Scholas, the wonderful training program where my youngest son is a digital marketing manager. (Check out the website, both to see his work and learn about an organization that might interest you.) Some physicians contend that since the office is an inappropriate, and at a minimum, suboptimal environment for addressing poverty, it is not in their individual job description to have much more than sympathy for the social determinants of health.

I can understand their mindset and the realities in their thought processes. It is even self protective because nothing burns you out more than trying desperately to do something that is important without having the adequate resources. On the other hand if our response is, “Not my job!” then how do we contribute to bringing relief to a huge problem. We do not say, not my job when it comes to cancer. We approach the job collectively at every level…

Joe’s response was terrific and deserves to be the core of another post which I will offer later this week. As I reflected on Joe’s question, Dr. Ebert’s insightful analysis come to mind.

“The existing deficiencies in health care cannot be corrected simply by supplying more personnel, more facilities and more money. These problems can only be solved by organizing the personnel, facilities and financing into a conceptual framework and operating system that will provide optimally for the health needs of the population.”

Ebert’s recommendation is now over 50 years old, but it is still valid and may be more valid today than it was when he articulated it in 1965. His analysis suggests that two large changes must be made if we hope to improve healthcare to meet the needs of the nation. The first change that he recommends is in how we finance care. The second change is in how we deliver care. At the end of my Musing on poverty my suggestion was that the medical issues associated with poverty should be addressed on multiple fronts. As a society we should return to the collective efforts that we tried to make with legislated programs in the sixties. I also implied that we need to create new ways to provide care and gave examples of attempts to more effectively deliver care from Whittier Street Health Center in the Roxbury neighborhood in Boston, and from Partners Healthcare. Finally I suggested that clinicians need to integrate being involved in mitigating poverty into their professional responsibilities.

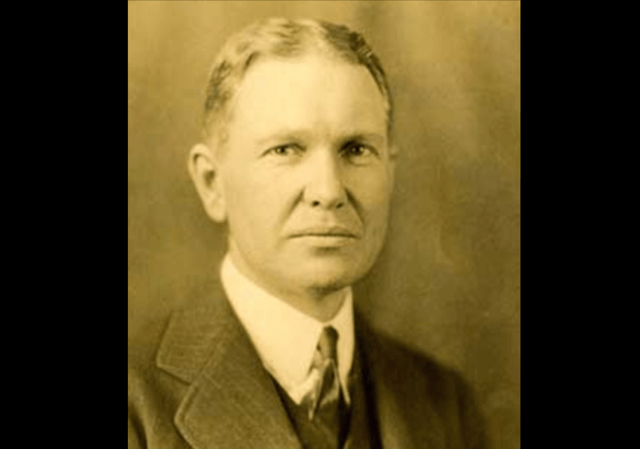

The solution, change the system, is a simple answer that has proven to be almost impossible to implement. The practice environment of most clinicians has not changed much since before Lindberg first flew solo across the Atlantic in 1927. 1927 was also the year that Dr. Francis Peabody (pictured in today’s header) delivered a lecture to Harvard medical students at Boston City Hospital during what would be the last year of his own life. His famous lecture, “The Care of the Patient,” has been given to medical students to read ever since he gave the lecture. It is a six thousand five hundred word piece that is a set up for its last sentence of twenty seven words.

One of the essential qualities of the clinician is interest in humanity, for the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.

I first read Dr. Peabody’s thoughts fifty years ago. I have returned to it several times since and discovered something new each time. I have mentioned it in these notes, but until now I have never connected it with the need to change the delivery system. As timeless as Dr. Peabody’s advice is, it is interesting to see that there are suggestions in his speech that the experiences of patients, physicians, and medical students were not optimal. His solution was to accept the professional responsibility of trying to make a difference for the patient no matter what the circumstances were. Dr. Peabody argues that despite the fact that it takes effort, the places where we meet the patient, the hospital and the office, are exactly the right places for clinicians to begin to understand the social circumstances of their patients, if they want to successfully treat them.

The care of the patient requires caring for the patient. If we care for our patients who live in poverty and know from our frustrated attempts just how hard it is to get to the root causes of their problems then that responsibility to care should also be a source of the collective resolve to move to more effective ways to deliver care as we go “up stream” to try to mitigate poverty at its sources.

An interesting paper, “Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals,” appeared in 2016 in the Canadian Medical Association Journal (CAMJ). The article is an effective review of the problems that poverty causes in healthcare delivery even in a nation that offers greater access to care than is available in America. Even in Canada, a country with a more robust social safety net, the individual clinician faces barriers when dealing with clinical problems that are rooted in, or exacerbated by, poverty and the social determinants of health. The author, Anne Andermann, MD of McGill University begins her article by saying:

There is strong evidence from around the globe that people who are poor and less educated have more health problems and die earlier than those who are richer and more educated, and these disparities exist even in wealthy countries like Canada. To make an impact on improving health equity and providing more patient-centred care, it is necessary to better understand and address the underlying causes of poor health. Yet physicians often feel helpless and frustrated when faced with the complex and intertwined health and social challenges of their patients. Many avoid asking about social issues, preferring to focus on medical treatment and lifestyle counseling. [ Here and below I have added bolding for emphasis.]

She offers a list of “Key Points” that include some things that physicians can do to make a difference.

Key points

- Although physicians generally recognize that social determinants (e.g., income, education and social status) influence the health of their patients, many are unsure how they can intervene.

- An increasing body of evidence provides guidance on a number of concrete actions that clinicians can use to address social determinants in their clinical practice to improve patient health and reduce inequities.

- At the patient level, physicians can be alert to clinical flags, ask patients about social challenges in a sensitive and caring way, and help them access benefits and support services.

- At the practice level, physicians can offer culturally safe services, use patient navigators where possible, and ensure that care is accessible to those most in need.

- At the community level, physicians can also partner with local organizations and public health, get involved in health planning and advocate for more supportive environments for health.

- Growing numbers of clinical decision aids, practice guidelines and other tools are now available to help physicians and allied health workers address the social determinants in their day-to-day practice.

She is addressing her Canadian colleagues, but I think we should eavesdrop on the conversation. Her conclusion is transferable:

Although addressing the social determinants of health requires a broad range of actions that involve collaboration of multiple sectors (e.g., education, justice and employment) and local, provincial and federal levels of government, physicians and other allied health care workers at the frontlines of clinical care are nonetheless important players and potential catalysts of change. They are well-positioned to support their patients in dealing with their social challenges; raise awareness of the human cost and suffering that results from poverty, discrimination, violence and social exclusion; and advocate for better living conditions to reduce health inequities and for more responsive health and social systems to care for those in need. Missed opportunities for prevention and inequitable access to care have been identified as major factors leading to inefficiencies in the health system. Therefore, leaders in Canadian health care increasingly recognize the need for a social determinants and population health approach “in reducing healthcare demand and contributing to health system sustainability.” Physicians are encouraged to implement their own creative solutions in their local context, measure the impact and share their successes in this important area of practice.

Don Berwick always suggests that we “think globally and act locally.” I would add that we should advocate globally and act locally. The motivation for those actions should be “the care of the patient” which is our fundamental professional responsibility.