4 January 2019

Dear Interested Readers,

We Must Address Poverty and the Social Determinants of Health

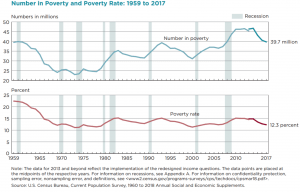

I have the opinion that most Americans do not understand or spend much time thinking about the term “social determinants of health”, or connect the expression to poverty. I also suspect that they feel that they have no more personal control over poverty than they do over the causes of global warming. I think most of us think about poverty in the way we think about cancer. We hope that we don’t get it and that our family and friends can avoid it. Most of us are really doing very well though many of us are worried that there may be financial problems in our future. The chart below shows that 87.7 % of us live above the poverty line. What the chart doesn’t show is the dynamics of poverty. There is substantial movement back and forth between those whose current status puts them in the population in poverty and those who will be in poverty at sometime in the near future. It seems that for very good reasons many of us who “have enough” in the moment fear falling into poverty, and that distorts how we view the problem. Wikipedia, quoting reliable sources, states:

Most Americans will spend at least one year below the poverty line at some point between ages 25 and 75. Poverty rates are persistently higher in rural and inner city parts of the country as compared to suburban areas.

It’s seems to be true that recently, perhaps because of the recession of 2008, that politicians are aware of this fear of financial vulnerability that exists within the middle class and have tried to use it to their advantage. Many of the “promises” and policy positions of politicians are framed around the status of the middle class or speak to the loss, or fear of loss, of jobs that yield a middle class income ($35-$100,000). We are frequently told that the middle class is shrinking. Nobody interprets a shrinking middle class as evidence that more people are wealthy. The knee jerk interpretation is that the number of people and families in the lower class and those in poverty must be growing. A recent New York Times article reports that the Pew Foundation has developed a calculator to help decide whether or not you are in the middle class. The threshold is a function of location and family size. If so many of us who think of ourselves as middle class are concerned about our own security in the middle class, it is easy to understand how there is so little attention from politicians left over for those in poverty.

Not only is there worry about the woes of a shrinking middle class, there is a debate about whether or not all of our social programs have made a difference. Some even argue that “government handouts” foster a culture of dependency and irresponsibility. It’s been over fifty years since Lyndon Johnson launched the “Great Society” programs plus Medicare and Medicaid as a “war on poverty.” Those who want to reduce federal spending on entitlements and say that social programs do not work see that 40 million Americans are in poverty now and that there were 40 million in poverty in 1960, and they site that as proof that all the money has been wasted. Advocates for less spending on anti poverty programs have had this opinion for a long time, but since the Trump tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy they have redoubled their advocacy for entitlement reform and reduction by any means. Why do you think there is enthusiasm in many “red states” for work requirements for many Medicaid recipients? Entitlement spending can still be reduced by creating administrative hurdles, even though the Republicans have lost the house and Paul Ryan is back in Wisconsin rereading Ayn Rand. Those that maintain that social programs are ultimately detrimental may even quote scripture (Matthew 24:11) to underline the fact that poverty is a natural state that can’t be eliminated.

There is much that the chart hides on both sides of the question of the effectiveness of anti poverty programs. It is true that we still have 40 million in poverty, but in 1960 there were only 180,000,000 Americans compared with an estimate of 325,000,000 in 2017. The numerator is the same but the percent in poverty has been cut in half. Things might be even better if much of the impact of the “War on Poverty” had not been lost because of the war in Vietnam that occupied us from the late sixties through the mid seventies followed by Ronald Reagan’s eighties war on “welfare queens.” Programs targeted against poverty and its causes have come and gone as recessions and business booms cycle and the administrative control of the government has alternated between Democrats and Republicans over the intervening years. Ironically, the earned income tax credit, EITC, has always enjoyed bipartisan support and is lauded by economists as perhaps the most effective program to lift families with children out of poverty.

Americans have a cultural bias toward self sufficiency. We believe that this is a land of opportunity. We celebrates those who have the initiative and entrepreneurial skill to go from rags to riches. Horatio Alger gave us many examples in stories that helped create the myth that it is possible for anyone who is willing to work to rise above poverty, enter the middle class, or do even better and become unbelievably wealthy. Over the last twenty five years a new class of legendary IT billionaires have added to the mystique. That mindset makes it easy for some to look at those in poverty and say “Not my problem.” If you want to believe that poverty is a permanent natural state occupied by those who lack personal initiative, have a history of impulsive behavior, or have consistently made bad personal decisions and refuse to make the personal decision to work rather than live on welfare, then poverty is not your problem. If that’s your viewpoint it is reassuring to point to those who have been able to lift themselves up as evidence that in America everyone has a chance to “make it.” In that mindset one rarely has any pity for those who don’t chose to help themselves, especially if you are apprehensive about your own economic security.

The problems that we have lumped together as the “social determinants of health” are essentially the same ones that Johnson’s War on Poverty was designed to address. I have spoken to clinicians who do not feel that the current “medicalization” of social problems is appropriate. When referring to the care of individuals their argument is hard to challenge. Poverty feels to them more like a “public health” issue that can’t be addressed effectively in their office or in the operating room. They are trained and equipped to diagnose and treat disease, perform procedures, or provide advice about how to improve or maintain the health of the individual patient. They were not trained in the resolution of societal problems. They would contend that while realizing that poverty plays a role in the origin of their patient’s problems, that does not mean they have the tools or responsibility to “fix it.” I know physicians and nurses who are frustrated, angry, exhausted, and even burned out by their personal attempts to ameliorate the impact of poverty on their patients. Those working in Federally Qualified Health Centers are essentially secular medical missionaries to the poor and disadvantaged.

It was just a few years ago that most clinicians thought of their responsibility to their patients only in terms of treating the problems brought to the office. We have more clarity now that many of those problems arise from poverty and its associated issues, but it is hard to imagine how we can do much about long standing social issues during a fifteen minute office visit. Most of the clinicians I have known over the years try hard to do what they can in their brief time with the patient to organize limited social services, provide useful personal advice, and offer some treatment for the acute problem before them. They offer their help to their individual patients while realizing that they lack the time or the resources to address the societal issues that shorten life expectancy, turn years that should be productive into years of illness and misery, and limit or reduce the possibility of the full measure of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” For many the term “population health” has become a challenge associated with inadequate resources. Some realize that getting everyone “covered” through a mechanism like an improved ACA, or alternatively through a more sweeping change like “Medicare for All,” won’t solve many of the problems they see in their offices or in the hospital. It also makes sense that even if everyone had access to care, it does not necessarily improve the health of the community, and certainly will not lower the cost of medical care when the root cause of much of the disease that we see today is driven by an inadequate societal approach to poverty and the associated social determinants of health.

Although there is little that individual clinicians can do during an office visit to address the social determinants of health that are the root cause of so many of the problems we see in the hospital and office, there are practices like the Whittier Street Health Clinic in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston that are making heroic efforts to address the social determinants of health issues in their communities. Larger health systems like Partners Healthcare in Massachusetts realize that in the new era of population health and risk based contracts they must develop programs that grapple with the social determinants of health and like Whittier Street Health Center are creating programs of community outreach. These programs are laudable like the efforts of dedicated clinicians working in the clinic and the hospital. They will make a difference in the lives of individuals, but they are not a substitute for the better engineered and effectively administrated reach of national programs built on the knowledge from the success and failures of previous attempts going back to Roosevelt’s New Deal and Social Security.

I mentioned earlier that some conservatives like to make the point that we read in Matthew 24:11 that Jesus considered poverty a problem that we will always have with us:

11 For ye have the poor always with you; but me ye have not always.

I have heard that reference since I was a child. It has not been until recently that I became aware of another scripture that addresses poverty. In Deuteronomy 15:11 we read:

11 For the poor shall never cease out of the land: therefore I command thee, saying, Thou shalt open thine hand wide unto thy brother, to thy poor, and to thy needy, in thy land.

The two scriptures are not contradictory. The reference in Matthew is about priorities at a specific moment. In Deuteronomy the admonition applies to how to manage a chronic social problem. Deuteronomy was written 2700 years ago. Carrying the admonition forward and applying it to a society of 325 million will take leadership that can create a consensus that there will be a common benefit from the effort. I hope that among the dozens of candidates who are expected to step forward to be considered for the presidency in 2020 a few of them will be audacious enough to offer ideas about how to further reduce the percentage of Americans in poverty to the low single digits, if not zero. Collectively we could chose to accept the spirit of:

…Thou shalt open thine hand wide unto thy brother, to thy poor, and to thy needy, in thy land.

Another piece of Jewish wisdom may apply here:

“It is not incumbent upon you to complete the work, but neither are you at liberty to desist from it” (Avot 2:16)

We may always have some people in poverty, but we are morally obligated to try to help. Helping them is also in everyone’s best interest. It’s a “no brainer” that helping people move out of poverty is not just a laudable and charitable obligation, it is an activity that will benefit all of us. It is good management and economic theory to help people move from dependency to full participation in the community. It is easy to forgive anyone for putting themselves and their family before others when they feel threatened or endangered. What is not easy to forgive are the words of politicians who create or foster the impression that we are vulnerable when we need not be if we would only work together toward achievable objectives . There will always be some people who have less than others, and in that regard they will be relatively “poor,” but there is no justifiable reason that anyone in this country experience hunger, have nowhere to live, or lack the opportunity to gain the training or support to be a contributing member of society.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. had a lot to say about poverty. He recognized that we are all connected:

“As long as there is poverty in this world, no man can be totally rich even if he has a billion dollars.”

Dr. King, “The American Dream” speech, 1961.

He suggested that our concerns about poverty should extend to everyone on the planet.

“God never intended for one group of people to live in superfluous inordinate wealth, while others live in abject deadening poverty.”

Dr. King, “Strength to Love”, 1963

He believed that we could make the choice to end poverty now:

“There is nothing new about poverty. What is new, however, is that we have the resources to get rid of it.”

Dr. King, Nobel Peace Prize address, 1964

And:

“The time has come for us to civilize ourselves by the total, direct and immediate abolition of poverty”

Dr. King, “Where do we go from Here: Chaos or Community”, 1967

I think if Dr. King could come back to see how we are doing he would assume that we must not have been listening to him, did not accept his assertions, did not share his level of concern, or see the opportunity we had since poverty exists at unacceptable levels fifty years after his assassination. Perhaps we have not seen “what’s in it for us” to end poverty or at least pick up our efforts to do so. I have mentioned Steven Pinker’s Enlightenment Now: The Case For Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress several times over the last few weeks. I have found the book to be a powerful argument for the collective benefit of using social programs to mitigate poverty and improve health. He underlines the progress that we have made, and speculates about why we feel so vulnerable when we are stronger and more capable than we have ever been before. Like Dr. King, Pinker points out the fact that we have the resources and the collective problem solving capabilities to continue to move forward on all fronts including poverty and global warming. As we solve those problems, we will also be making progress toward the Triple Aim. Without addressing poverty it is hard to imagine getting ahead in the management of the chronic diseases that are the scourge of so many who live in poverty. Addressing poverty will enable the engagement necessary to create healthier communities.

Each New Year is a chance to reflect on the last year’s successes and failures and to use the results of that analysis to try again to solve the problems that face us. Pinker’s positivity is grounded in his appreciation of what we have accomplished over the last 250 years of “enlightenment,” and his belief that never before have we had the knowledge that we have now to enable our reasoning, our use of science, and our humanistic expression of sympathy for one another to make progress on the problems that confront us.

Pinker wrote his book after the election of President Trump and before we elected a Democratic majority in the House at the 2018 midterm election. Now with “divided government” we have a way to balance the president’s view of the “carnage” that he said he was elected to resolve by putting America first. Pinker pointed out that the state of carnage that Trump described in his inaugural address was a gross misrepresentation of where we were in 2017, but the path that he has tried to put us on since becoming president does possibly lead to something like “carnage.” Trump characterized America as weak and vulnerable, and offered himself as the only solution to our desperate state. He gave lip service to a belief in the inherent strength of the institutions of our government and society, but since taking office he has consistently tried to undermine the press, interfere with the performance of independent agencies, and extend his power through the use of administrative orders. So far our institutions of democracy have defended us from a total unraveling of the progress we had made during his populist drift toward authoritarianism. ( I will always be thankful for the courage of John McCain; may he rest in peace.) Now there is evidence that Pinker was right. The institutions have held so far and now the House is positioned to be a greater check on deviation from our previous norms.

I do not expect the Democratic majority in the House will enable the immediate passage of new programs to address poverty and the social determinants of health, but it could be a beginning. There is much work to do. We still are in the midst of a potentially destructive struggle, but now we do have more than just humor and hope to sustain us. I hope that clinicians who feel overwhelmed by patients who have problems that can never be solved until we address a host of social issues can find some encouragement in the eventual possibility that someday in the next few years we will celebrate the use our collective wealth to allow everyone to have a better chance at the health and happiness we should all share.

Enjoying the Long End of Winter After the Holidays

On Sunday afternoon we are attending a gathering called an “Aren’t You Glad the Holidays Are Over” party. Now that our family and other holiday guests have come and gone and the house has been de decorated, I am looking forward to seeing friends and neighbors and hearing about their holiday experiences. It’s still a month until the Super Bowl, two months until spring training, and three months until opening day. We are now into the longest part of winter, but there are less dramatic joys available even when it’s cold outside.

At this time of year many of my friends and neighbors say, “This is not for me.” They head out for Florida or Arizona saying, “I’ll see you after mud season.” Even I will be going to Florida for a few days in February. I’m not fleeing the weather. I am going to attend “Grandparents’ Day” at my granddaughter’s high school and watch her play in a volleyball tournament. Otherwise, I am here for the long haul. I plan to do some winter walking, and perhaps some hiking, snowshoeing, and cross country skiing. Otherwise, I will read by the fire, play some dominos, try to get better with my guitar, and be open to the beauty around me.

I have featured several headers in the past that I have taken as screen shots from the beautiful drone photography of my neighbor, Peter Bloch. If you have read this far, I hope that you will click on the link and spend another five minutes and view the video from which I have lifted today’s picture. The clip will provide you with a few minutes of respite from the weight of winter’s burdens. It could even be the stimulus that you need to get out and enjoy some winter exercise this weekend.

Be well, take good care of yourself, let me hear from you often, and don’t let anything keep you from doing the good that you can do every day,

Gene