I believe that without the total commitment of senior leadership, especially the CEO, Lean can’t succeed. Leadership can launch Lean or leadership can tolerate Lean and enjoy the benefits that it offers for a while, but if leadership wants Lean to be a sustainable source of competitive advantage then it must lead Lean. It must follow Gandhi’s advice and “become the change it wants to see”. The C-suite must seek its own transformation and be open to continuous learning if it expects to lead an organization that has the capacity for continuous improvement.

Many senior leaders misunderstand Lean and what makes it successful. Lean is more than a collection of tools to solve urgent problems over the next few financial cycles. Despite what Lean can accomplish when used as a tool to fix the ER or increase performance in the OR, an organization is wasting money if the senior management offers no more than casual support or is just tolerant of Lean. Worse yet is when the CEO tries to tap into the benefits of Lean by proxy while continuing the traditional “Sloan Management” top down process of management by objective. If the CEO and senior leaders do not effectively do the “standard work” of Lean leadership, it would be better for the organization to buy lottery tickets than spend money and effort trying to implement Lean with leadership sitting on the side lines. Conversely, with the total commitment of senior management, Lean sometimes fails to create long term sustainable competency and a sustainable competitive advantage. Professor Rebecca Henderson from Harvard Business School has asked why the desire to succeed with Lean is necessary but insufficient for sustainable competitive advantage and her answer is documented in a paper, “Relational Contracts and the Roots of Sustained Competitive Advantage” that she wrote in early 2013.

I was a CEO who was committed to Lean and hoped it would produce a sustained change in our organization but found that there were complexities that made the job difficult and searched for the competencies that we needed to enhance if we were going to make real progress with Lean. During my tenure Atrius Health functioned on a “federalist” platform. Individual groups had substantial “reserved powers”. There were many similarities but also significant variations in culture across the organizations that made up Atrius. The internal realities that were a barrier to change within Atrius were not unlike barriers to Lean success that I see now in large IPAs, CINs and recently merged healthcare systems.

Professor Henderson’s search for the sources of sustained competitive advantage offered me insights. She “hooked me” from the start of her paper where she pointed out that organizations like Toyota had organizational competencies, like Lean, but their success with Lean was more than just competence with Lean tools. She postulated that the source of their sustained competitive advantage was based in some “soft competencies” that were difficult to replicate. explaining why it was hard to “be” Lean.

Professor Henderson’s focus on Lean answered part of the question of why several companies, not just Toyota, were able to far out distance their competitors by offering better value, year in and year out obviously intrigued me. She was asking and attempting to answer questions about the origins of superior performance that I had been asking myself. Her research showed that “high commitment work systems” were key to success and that these systems had three key elements.

- High powered incentives (not just money, but security, feedback,recognition, and an opportunity to grow)

- Skills development

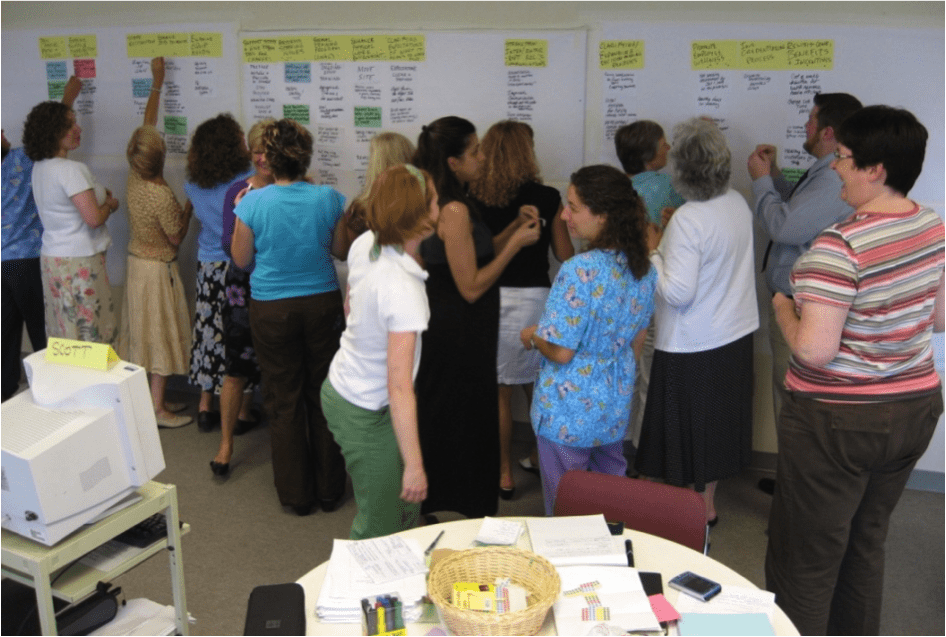

- Dense communication and local problem solving

She then posed a question that spoke to my concern:

The evidence that differences in organizational practice are associated with significant differences in performance is thus quite compelling. The puzzling question then becomes why they [Lean skills] don’t diffuse more rapidly. .. If better organizational capabilities are behind the success of firms like Toyota …., why don’t their competitors simply imitate them? What is going on?

She postulates four explanations:

- First, managers may have problems of perception— … many very successful firms come to believe that they have little to learn from their competitors …

Large systems which have been dominant do not have competition that drives them to be better. Virginia Mason was under significant financial stress when Gary Kaplan “found” Lean. Patty Gabow at Denver Health was motivated to use Lean to stretch the public dollar to provide high quality care in an environment that is always short of resources. John Toussaint was motivated to turn to Lean to provide quality and better service much more than to improve finance. Many of our bigger systems and dominant regional systems are still getting by doing things the old way and are not yet interested in changing.

- Second, managers may have problems of inspiration —they may see that their competitors are performing better than they are but they don’t know exactly what their competitors are doing that makes the difference…

Again, I see similarities in healthcare today. Systems that are managing by objective and are driven by concerns about the bottom line create oppressive environments of fear and make cuts that increase fatigue and burnout as they struggle to generate revenues that are slightly greater than expense producing a meager bottom line. The “still successful” are not open to paying attention to the “softer” elements that drive success with Lean. Those softer elements look like avoidable overhead in a very stressed system.

- Third, managers may have problems of motivation —…Managers who have built their success on managing …using a more conventional style…may find the suggestion that they embrace a very different way of managing people deeply threatening to their own position, and may resist the idea accordingly.

BINGO! This is the big one. Self interest within a large enterprise is often in conflict with the best interest of the system and those who are doing well will pull out all of the stops to maintain the status quo even while others suffer.

- Fourth, managers may run into problems of implementation —they may know they’re behind, they may know what to do, and they may be trying hard to do it, but for some reason they nonetheless cannot seem to get the organization to get it done.

This is the point that contains the easiest solution if management and the board has insight and realizes that they need help. The good news is that there are very capable sources of guidance for those of us in healthcare who have decided that there is promise in Lean and want help learning the language, understanding the tools and finding the “secret sauce” of the “softer” competencies that are necessary for sustained success.

Professor Henderson asks a second key question: Why should implementation be hard?

One possibility is that the implementation problem is one of “complementarities” – that high performance work systems cannot be adopted piece meal but must be adopted as a bundle, and that this is extremely difficult because firms tend to make changes only slowly and incrementally.

“Why does it need to be so hard?”, is certainly the first questions most potential clients ask when they call in a Lean consultancy for a conversation about “doing Lean”. Just knowing how and where to begin a Lean transformation in a large complex medical enterprise does present a huge strategic concern. After examining why it is hard for organizations to establish Lean as a source of sustainable long term competitive advantage, Professor Henderson pivots somewhat shifting the focus to the “softer competencies” necessary to build relational contracts. She asks:

Is it hard to develop new organizational competencies because it’s hard to build new

relational contracts?

…implementation may be hard because the kinds of organizational competencies that lead to competitive advantage rely on the presence of “relational contracts” within the firm, and that these contracts are hard to build and difficult to change once built.

A “relational contract” is an understanding between two or more parties that is based on

subjective measures enforced by the shadow of the future rather than by the threat of legal action.

Successful Lean organizations are built on the trust and clarity between leadership and employees that is necessary for everyone as an organization moves into the uncertainty of what transformation will mean. It is easy for the CEO to say that the motivation for doing Lean is to cut waste, not people. It is easy to announce that there will be respect and a focus on quality. It is also easy to say that those doing the work will be involved in defining standard work and creating new innovative processes of care across silos. It is easy to promise that employees can design workflows that reduce stress or burnout.

It is hard for people to understand and believe what they have never seen before, especially if they do not see any changes in leadership. Promising a “new way of walking” sounds great unless you fear it is a “bait and switch” or the “flavor of the month”. “Trust me things will be different this time” rarely works in any environment without a real demonstration of commitment that leads to assurance. Trust dies easily and is almost impossible to revive when violated. Professor Henderson expands the discussion of relational contracts:

…a relational contract is a very specific form of “trust”. To the degree that we define trust as a well rooted expectation that another person will behave in a specific way, managers and employees linked by a successful relational contract can be said to trust each other. The manager trusts the employee to do the right thing and the employee trusts that if they do so they will be rewarded appropriately.

These issues are more complicated than they appear on the surface. We all think we are authorities on trust and mistrust. We prefer insurance over assurance as protection from feeling vulnerable. Once again Professor Henderson helps us understand why building effective relational contracts is difficult work.

Recent research suggests that there are two potential explanations: the problem of credibility and the problem of clarity…

Problems of credibility arise if both parties understand the structure of a potentially beneficial

relational contract in principle but if they don’t believe that the other party has incentives to adhere to it. …–suppose that the firm enters a major cash flow crunch, for example, will they keep their promise not to lay me off?…

Think about it. How often do you “discount” what the CEO might say or what your team leader says? We certainly discount almost everything a very earnest politician says he/she will accomplish if elected.

The problem of clarity is a concern for many CEOs attempting to lead a Lean transformation.

Developing new relational contracts may be made even more difficult by the problem of clarity…we have assumed that a manager can communicate to employees what “cooperation” looks like…the difficulty in building a relational contract lies in the fact that she cannot credibly communicate the precise values of her payoffs, discount rate or time horizon… building a relational contract in the real world may be a less than straight forward exercise. Maintaining it once built may be even harder. Once we think about the complications inherent in building relational contracts in practice, the hypothesis that the ability to build and maintain them might be an important source of competitive advantage becomes quite plausible.

After reading Professor Henderson’s paper, I realized that at the top of the list of my “standard work” as CEO was a responsibility to develop and maintain the relational contracts upon which the security of our practices rested. Creating credibility and clarity required the effort to be authentic in my own Lean involvement and to redouble my efforts to understand the “standard work” of being a Lean leader.