Following the recent “Healthcare Musings” weekly letter where I described my experience participating in “healthcare war games” a very faithful “Interested Reader” wrote to me:

An uncharacteristically downbeat letter, Gene, but interesting and challenging. I sent you a response a while ago about the usually very powerful forces behind any status quo, and this is an excellent, though not in a good way, example of that point. The 19th C American reformers, especially anti-slavery and anti-alcohol, vigorously debated the persuasion/compulsion options. Both issues were, of course, ultimately resolved by compulsion. This may be a similar kind of issue, where the compulsion will come from governmental and private payors. In those old debates, I expect that you would have inclined to the persuasion side because that is based on the belief that people will do the right thing if only that can be brought to see the truth…

I have always been aware of the power of the status quo to resist change. Perhaps my friend was reacting to my sarcastic comments about the clouds that shade our hopes for the Triple Aim and the low likelihood that it will be achieved anytime soon. I did say:

The introductory comments to the “war games” excited me when I heard that the objective was the Triple Aim. As the first hour of discussion introducing the exercises came to an end I had to admit to creeping realism and a growing cynicism. I kept my self righteous thoughts to myself. What was going through my mind that perhaps I did not have the courage to point out was that the goal was not really the Triple Aim, but rather a revision which I described as “two heavily qualified hopes and one impossible dream”.

The most important idea in my pen pal’s note was not the question of my mood but his use of history to speculate on how change will occur in healthcare. It was a discussion of the relative value of carrots and sticks. What is also unique in this moment is that both CMS and private insurers are picking up sticks, although they are attempting to hide them in velvet sheaths.

My interested reader knows me pretty well when he suggests that I prefer persuasion or carrots to compulsion or sticks. It is my nature to be drawn to leaders who are advocates for the common good. My heroes are women and men like Eleanor Roosevelt, Dorothy Day, Frances Perkins, John Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr., Bobby Kennedy, and Don Berwick.

Who among us is not moved or at least for a moment pauses and reflects when we hear a phrase like:

My fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.

or :

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

Most Americans have never heard of Frances Perkins, or if they saw her name on the front of the offices of the Department of Labor, just off the Mall in Washington, they would not know that there are few people who added more positively and without personal profit to our society than she did as the first woman in a Presidential cabinet. She said many inspiring things like:

Out of our first century of national life we evolved the ethical principle that it was not right or just that an honest and industrious man should live and die in misery. He was entitled to some degree of sympathy and security. Our conscience declared against the honest workman’s becoming a pauper, but our eyes told us that he very often did.

We owe much of what we enjoy today as social security and the concept of a minimum wage to her sense of what is right and her commitment to an ideal. By nature I am also drawn to the patient but active methodology for change advocated by Bobby Kennedy:

Few will have the greatness to bend history itself, but each of us can work to change a small portion of events. It is from numberless diverse acts of courage and belief that human history is shaped. Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.

In healthcare I have looked to Don Berwick for more than a quarter century for the words that persuade and sustain me. His words always reveal the facts that we do not want to face or have ignored and the human reasons that we should no longer be deaf to the call to do something.

The quest is clear. It’s not power or accountability or reward or punishment or score sheets or metrics or profit for its own sake. It’s a search for meaning in the value of the person who has come to honor us with his or her quest for some help.

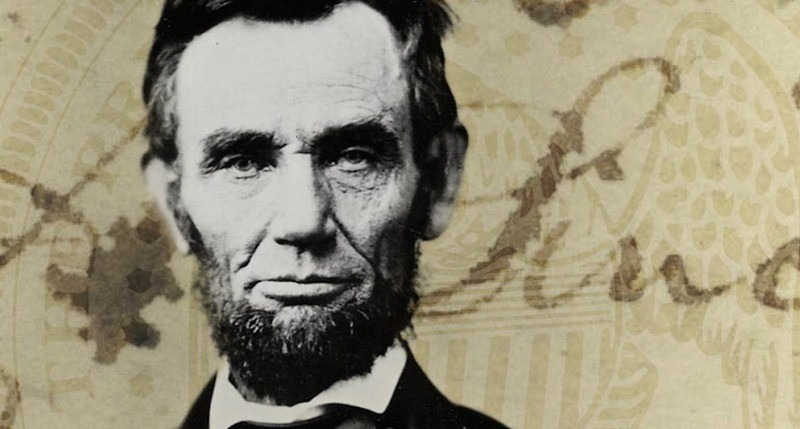

My Interested Reader points out that much of the measurable progress on the larger social issues that have faced our society has occurred through the action of the agents of compulsion like Abraham Lincoln, Thurgood Marshall and Lyndon Johnson. What is missing in his analysis is the interaction between long suffering persuasion and definitive compulsion. What would Johnson have been able to do for Civil Rights through legislation or “compulsion”, as my reader infers, without the simultaneous efforts at “persuasion” being pressed by Dr. King and those who responded to his call? Would Lincoln ever have had the opportunity to sign the Emancipation Proclamation or the insight to push for the 13th Amendment had it not been for efforts of committed public figures like Thaddeus Stevens (as depicted by Tommy Lee Jones in Stephen Spielberg’s Lincoln) and the well organized abolitionists like Harriet Tubman whose image will grace our new twenty dollar bill. Stevens was remarkable because history reveals that he had the insight and courage to tame his tongue and modify his objective to achieve an improved state that was less than the perfection of full equality that he wanted. Perhaps it was what I witnessed in the South during the Civil Rights struggles of the fifties and sixties that makes me aware of the realities of the “persuasion/ compulsion” options.

If you combine the votes of those advocating for America’s “return to greatness” with those seeking to end of the “advantages of billionaires” it is easy to explain the bizarre events of this presidential election cycle. The majority of voters are dissatisfied with the status quo. If we survive this year, it will be because a majority is willing once again to trust that the changes in the status quo required to achieve justice still can be negotiated within the framework laid out by the Constitution.

What I witnessed at the “war games” was like powerful theater demonstrating just how persuasion and compulsion can interact creatively to change the status quo. We were play acting but we participated in the hypothetical scenarios as actors who really knew their roles from experience in the real world and whose performance in the play was likely to be highly predictive of the actions that they or others like them would take in real life. All of the actors had “been to the theatre” in the real world of healthcare.

Our imaginary market, “San Optimo”, was in a “red state” that had not accepted the Medicaid expansion of the ACA, but had lower than average Medicare costs. In San Optimo there was cost shifting from expensive commercial insurance to cover bad debt from the uninsured and to provide comfortable incomes for providers and institutions. Even though there was a large uninsured population that generated bad debt for institutions and poor care for those without coverage, at the steady state the majority of providers were satisfied with the status quo and threatened by suggestions of change. Employers were unhappy with the costs they were forced to bear and taxpayers were unwilling to extend Medicaid to their neighbors in need.

One of the players or actors at my table had been one of the architects of the Harry and Louise resistance to the 1993 attempt by the Clintons at healthcare reform. I found him to be incredibly believable, positive, informed, focused and ethical in his role in our imaginary community as he played the role of the CEO of a for profit hospital system. Things in our play world and in the real world are never as black and white as they are in the literature or in a political debate. This new acquaintance does not reject the principles of the Triple Aim but he does want to protect a constituency that he is aligned with and benefits from as we make the transition from volume to value.

The persuasion/ compulsion interaction in the real world was demonstrated recently at a conference I attended on the stress of moving from volume to value. The story was one told by a hospital system that could have been in “San Optimo”. This hospital system is in a moderate sized city with a good university and medical school. It faces increasing possibilities of financial loss through bad debt. It is in a red state with a well publicized history of racial tension. Its legislature has attempted to enforce limits on personal choices that offend conservative Christians. The state has refused to expand Medicaid through the ACA and over 20% of its population is poor by any standard and uninsured.

There is no DSH hospital in this market. All of the hospitals take care of large uninsured populations but still make a small margin because of cost shifting from commercial payers. The hospital management is responsible and very concerned. What can they do?

What they chose to do was an excellent exercise in population health and compassion that was the result of persuasion and the reality that they sense compulsion is coming. They identified a population of underserved patients who had issues of chronic disease and behavioral health and frequently came to their emergency service and had to be admitted because of the severity of their illness. Remember, we have had a law since 1986 that forbids us from allowing people to die in the street. Remarkably, they decided to do something different. They established and funded a system of free care that provided outpatient resources that were geographically proximate to the patients and designed to meet their needs with the prospective goal of improving their health!

The result was a dramatic reduction in EW use, hospitalizations, and bad debt. The quality metrics and health of the patients improved. The reduction in bad debt was greater than the investment from the hospital’s margin! This also could theoretically mitigate the extra costs that employers bear as they funded, whether they knew it or not, the hospital’s cost shifting.

This is an example of “persuasion and compulsion” in action in concert. I would propose that it was a function of Don Berwick like sensibilities arising from providers and a delivery system that cares about its community, warts and all, and is also aware that things are inevitably changing. They realize that they need to begin to explore what the shift from volume to value might mean for them. They were doing Triple Aim thinking and their little pilot will provide enough heat to keep my flickering hopes alive for yet a little while. It is not time to give up. It is time to learn how to effectively manage the balance between persuasion and compulsion.