The core ideas of what the IHI calls the Triple Aim were articulated by Robert Ebert, Dean of Harvard Medical School in 1965. Our understanding of the Triple Aim was accelerated by two important books, To Err is Human (1999) and Crossing the Quality Chasm (2001), which described safety, patient centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, effectiveness and equity as “systems properties” in high functioning systems of care.

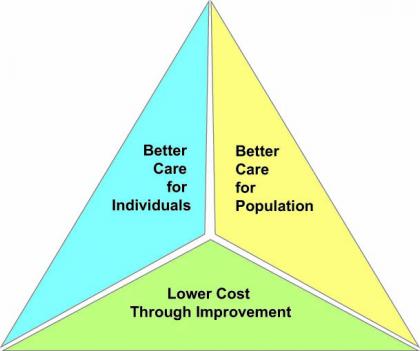

The Triple Aim is the objective of the high performing systems of care that we desire. The three “legs” of the Triple Aim: improving the individual experience of care; improving the health of populations; and reducing the per capita costs of care for populations, are the output of those new and better systems.

Large scale change takes time. Our collective progress toward the Triple Aim has been too slow. Its vision has not become the guide for the strategies of all of our systems of care or for all individual healthcare professionals. The ACA and the movement from “volume to value” are expressions of the Triple Aim. Although they are necessary, they are insufficient to insure that we will eventually have:

Care better than we have ever seen, health better than we have ever known, cost we can all afford, …for every person, every time.

Despite a slowly growing awareness, the Triple Aim has not united everyone or even a majority in the pursuit of the better care we all profess to want. It has not overcome the inertia of conventional health care finance, the mindset of two millennia of medical culture, and the short term and immediate self interests of patients and physicians. The status quo in all of its manifestations remains a bulwark of barriers to the promise of the Triple Aim. Despite eight years of explanations and exhortations, the Triple Aim is not the vision of the majority.

If we believe the Triple AIM has the power to become the vision that unites our efforts to improve care then perhaps we should return to the landmark paper that first explained the Triple Aim, published by Berwick, Nolan, and Whittington in the May/June 2008 edition of Health Affairs, “The Triple Aim: Care, Health, And Costs” . Before this article, the Triple Aim was about as generally understood and accepted as the way forward in healthcare, as was the concept that that world was round in 1492 when Columbus sailed into the sunset to get to the East. Ironically, since the article was published its truth has been ignored almost as effectively as the purveyors of carbon-based energy sources have ignored the messages of science about the origins of global warming.

The authors introduce us to the need for the Triple Aim by reminding us of wasteful readmissions for CHF. They did what most of us who were managing this revolving door did not do and asked two questions, “Why?” and “Can we do better?” They answered the second question by reminding us that carefully managed programs had reduced readmissions by 80%.

“Why?” was a little harder to answer, but they saw the problem as a systems issue. Care was fragmented. Handoffs were ineffective. The system failed both patients and clinicians.

They presented a three point indictment of our healthcare system: first, it did not cover everyone; second, it was two or three times more expensive than in other advanced economies; and third, care was much less effective than in those other industrialized nations. They observed that the quality movement was making very slow progress toward improving the care of individuals and no measurable progress toward lowering the cost of care. Once again they asked “Why?” and “Can we do better?” The answers were that change is hard; and yes, by embracing the principles of the Triple Aim, we could do much better.

They were concerned that “too few improvement efforts address defects in care across the continuum, such as those that plague patients with CHF.” They asserted that alignment across the continuum of care would be necessary to “improve site-specific care for individuals.” They proposed a new approach to advance the pursuit of quality for everyone.

…the United States will not achieve high-value health care unless improvement initiatives pursue a broader system of linked goals. In the aggregate, we call those goals the “Triple Aim”: improving the individual experience of care; improving the health of populations; and reducing the per capita costs of care for populations.

Their insight was that the goals of the Triple Aim were interdependent and that interdependence was a benefit in some areas and a problem in other areas. They recognized that improved health in one population could, but should not, “be achieved at the expense of another subpopulation.” They felt that “a health system capable of continual improvement on all three aims, under whatever constraints…looks quite different from one designed for the first aim only.”

They dropped a bomb with a diagnosis that persists today:

“…the balanced pursuit of the Triple Aim is not congruent with the current business models of any but a tiny number of U.S. health care organizations...For most, only one, or possibly two, of the dimensions is strategic, but not all three. Thus, we face a paradox with respect to pursuit of the Triple Aim. From the viewpoint of the United States as a whole, it is essential; yet from the viewpoint of individual actors responding to current market forces, pursuing the three aims at once is not in their immediate self-interest…. Rational common interests and rational individual interests are in conflict.

They used Garrett Harden’s concept of the “tragedy of the commons” to further explain the tension that existed between the individual and the community or between one practice and all practices. Their solution is a shared vision that was larger than self interest and that encouraged collective action.

…the Holy Grail of universal coverage in the United States may remain out of reach unless, through rational collective action overriding some individual self-interest, we can reduce per capita costs.

The authors knew that other barriers would still exist even if we got beyond the barriers arising from self interest. Their hope was that our ability to innovate as a response to challenges would lead to changes in how care was delivered that might support the realization of the goals of the Triple Aim. Their solution to the barriers:

We suggest that three inescapable design constraints underlie effective accomplishment of the Triple Aim: (1) recognition of a population as the unit of concern, (2) externally supplied policy constraints (such as a total budget limit or the requirement that all subgroups be treated equitably), and (3) existence of an “integrator” able to focus and coordinate services to help the population on all three dimensions at once.

They went even further to anticipate the confusion about “populations” and then introduced the utility of registries. They wrote:

A “population” need not be geographic. What best defines a population, as we use the term, is probably the concept of enrollment….A registry that tracks a defined group of people over time would create a “population” for the purposes of the Triple Aim. Other examples of populations are “all of the diabetics in Massachusetts,” “people in Maryland below 300 percent of poverty,” “members of Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound,” “the citizens of a county,” or even “all of the people who say that Dr. Jones is their doctor.” Only when the population is specified does it become, in principle, possible to know about its experiences of care, its health status, and the per capita costs of caring for it.

The authors cited “policy constraints” after “populations” as a second challenge.

The policy constraints that shape the balance sought among the three aims are not automatic or inherent in the idea. Rather, they derive from the processes of decision making, politics, and social contracting relevant to the population involved.

Those questions brings us to the third important consideration in the evolution of the Triple Aim, “the integrator.” What is an ACO if not an integrator?

An “integrator” is an entity that accepts responsibility for all three components of the Triple Aim for a specified population. … The simplest such form, such as Kaiser Permanente, has fully integrated financing and either full ownership of or exclusive relationships with delivery structures, and it is able to use those structures to good advantage. We believe, however, that other models can also take on a strong integrator role, even without unified financing or a single delivery system….In crafting care, an effective integrator, in one way or another, will link health care organizations …whose missions overlap across the spectrum of delivery. It will be able to recognize and respond to patients’ individual care needs and preferences, to the health needs and opportunities of the population … and to the total costs of care.

They finish with a prediction that has been proven true and is the reason why I believe that we must renew our efforts to make the Triple Aim the strategic vision of everyone in healthcare.

From experiments in the United States and from examples of other countries, it is now possible to describe feasible, evidence-based care system designs that achieve gains on all three aims at once: care, health, and cost. The remaining barriers are not technical; they are political. The superiority of the possible end state is no longer scientifically debatable. The pain of the transition state—the disruption of institutions, forms, habits, beliefs, and income streams in the status quo—is what denies us, so far, the enormous gains on components of the Triple Aim that integrated care could offer.

Against that background, it is no longer audacious to hope for a day when we have healthier communities where we enjoy….

Care better than we have ever seen, health better than we have ever known, cost we can all afford, …for every person, every time.