I have had the feeling, and I know that it has been shared by many of you, that 2020 was the most difficult year that I can remember. Against that universal feeling, or perhaps because of it, The Washington Post published an editorial last week entitled “20 Good Things That Happened in 2020.”

They started the series a few years ago. You know “16 Good Things That Happened in 2016.” I can think of one bad thing that happened that year. In 2017 it was “17 Good Things That happened in 2017.” I will always remember 2017 with the image of John McCain’s thumb going down to save the ACA. It was also the year my youngest grandson was born. Understandably, 2017 will always be a great year for me. The editors said that they expected that as the years went by their little game would be gradually harder since the number of items on the list would grow year by year. Like all of us, they had no possible way this time last year to know the extent of what was just ahead of us.

They decided that this year was one of “silver linings.” My own example of a silver lining would be like, “I was a victim of a terrible auto accident, but while I was in the hospital I met a nurse who became my wife.” [That is a fictitious example. I met my wife for the first time in a cath lab, and then again several years later.] Do you get the idea? Not to steal their thunder, they write:

“Yes, a terrible plague struck humankind, but…” We don’t apologize for that; finding the silver linings is how we all make it through. And we’re sure this list is far from exhaustive; we’d love to hear from you. What good things happened in 2020 that we’ve omitted here?

Perhaps their first “good thing” is the best example of their “silver lining” philosophy:

A terrible plague struck humankind, but scientists responded with unprecedented speed and common purpose; cooperating across national lines to decode the virus and then discover and manufacture vaccines that can prevent the disease.

That one is hard to beat, but I might have given the number one vote to the “good thing” that they ranked #3:

We learned to appreciate the selfless dedication of nurses, orderlies, doctors and other health workers who risked their lives to save ours — and the selfless dedication of truck drivers, grocery stockers, farmworkers and so many more who risked their lives to keep the economy from collapsing.

I also liked #7:

A record number of Americans turned out to vote in our national election, pandemic notwithstanding.

Many people would have put #9 in the top position:

And… he lost. We realize that for 74 million Americans, that doesn’t count as a good thing, but the result was welcomed by 81 million — ourselves among them. And this is our list. We celebrate the defeat of the worst president in U.S. history.

I was totally surprised that the editors were able to articulate a “silver lining” positive out of the murder of George Floyd, but they did. It was #15.

One of the most horrifying acts of police brutality ever caught on video — the killing of George Floyd — led to an outpouring of protest and reflection and, in many cities and state capitals, the beginning of reform.

If you are wondering if they specifically named the election of Joe Biden as one of the twenty good things in 2020, they did in sort of an indirect way with a combination of #9, #10, and #20. #9 was about Trump losing, #10 was the celebration of the pivotal role that Black women played in the election. It read:

Black women led the nation to this fortunate result, with more than 9 in 10 voting for Democratic candidate Joe Biden in an election that was far closer than it should have been.

#20 was the opportunity for diversity that Biden’s election created:

After four years of an administration appointing mostly White men to the judiciary and the executive branch, the government was set to look more like America. And not just with its new vice president, but with a plethora of new faces including the most Native Americans elected to Congress, the most trans people elected to state legislatures, a burst of Republican women elected to Congress and a highly diverse and competent array of nominees for the incoming Cabinet.

I get the fact that Joe is not as exciting as Barack Obama or Bill Clinton. He is not as provocative as Donald Trump, or as smooth as Ronald Reagan, but he is a man who has learned many political, and social lessons over a very long career. There has never been a more empathetic person than Joe Biden in the Oval Office. Trump demonstrated his lack of understanding of his opponent when he would ask the crowds at the rallies during his ill-fated campaign: “What has Biden done in the 47 years he has been in Washington?” The Miami-Dade Democratic Party decided to answer that question. You can read the long list of his accomplishments that they posted, but the short answer is actually, “More than you might know or that Donald Trump can appreciate.”

I do not envy what Joe Biden has ahead of him. Barack Obama entered the presidency with Mitch McConnell saying that his number one job was to make Obama a one-term president. President Trump seems determined to block Joe Biden from even beginning his term, much less having a second term. If we do get to January 20 without riots and marshall law, Trump seems intent on continuing to control the hearts and minds of his base with his lies. By the end of the campaign, he was telling more than fifty whoppers a day. With his lies and refusal to admit that he lost he is attempting to prevent Biden from ever having a chance to pass meaningful legislation. With millions of Republicans across the country believing the greatest lie of all–that he did not lose the election–he will be an alternative focus for the press and a persistent looming and ominous presence for the next four years.

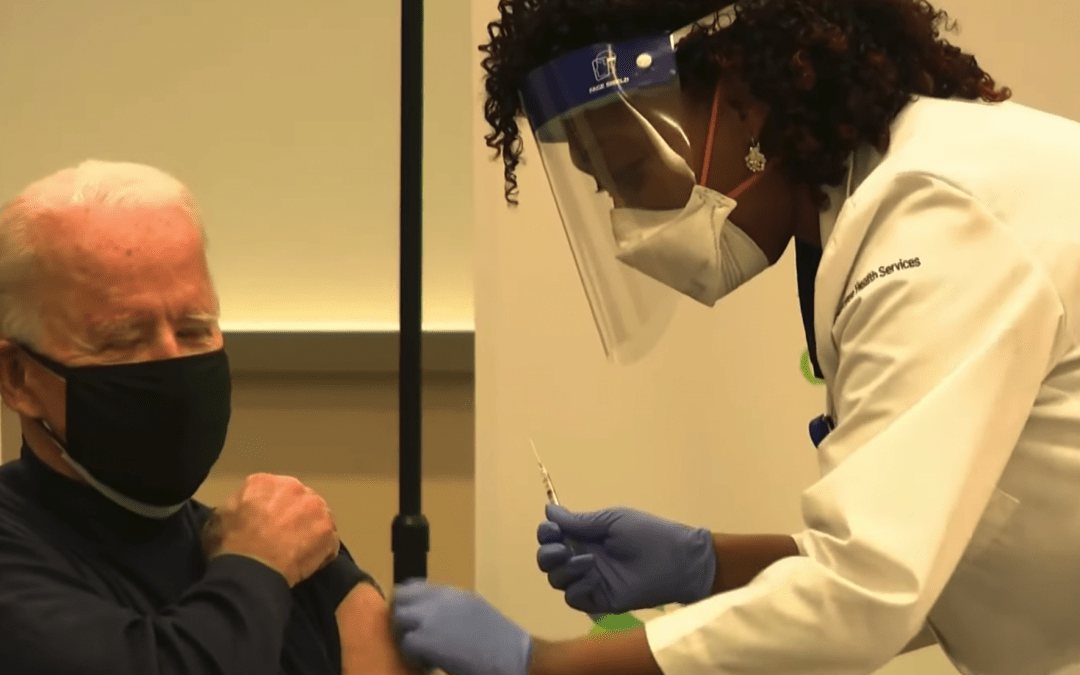

While Trump seeks to negate Joe’s presidency before it starts, I am impressed by Biden’s efforts to signal to us that there is good reason to hope that his election was really #1 on the list of good things that happened in 2020. Since the election, we have heard nothing much from the president about the pandemic except how he gave us the vaccine in record time. He has expressed absolutely no remorse for the more than 300,000 lives lost, but many times a day he offers tweets containing his mantra about how the election was a fraud. At the same time, Joe has stepped up and expressed his continuing sorrow and his resolve to end the pandemic. He showed us that he is not afraid to take the vaccine. [In fairness to Trump, it is not clear to experts when he should get his shot since he got antibodies when he was infected.] Nevertheless, small gestures mean a lot at a time like this when many voters don’t believe you won, and many of the people whose support elected you don’t trust the government enough to take a vaccine that the government pushed through in record time.

Barack Obama’s first volume about his presidency, A Promised Land is currently number one on the nonfiction best-seller list. 1.7 million copies were sold in the first week. If you did not buy a copy there is a good possibility that you will get one as a Christmas present.

In the book, Obama does more than try to celebrate his accomplishments or express disdain for those like McConnell who tried to undermine his objectives. In part, he is offering explanations for those who criticize him for what he was not able to accomplish after raising their hopes. He spends a lot of time talking about the power of the press and how the nation’s attention span is short. He doesn’t offer the reality of the fickle press as an excuse. It is more that he is offering his experience with the news cycle as an example for those who will come after him who might come to the office of the president offering the hope that their election will fix long-standing problems. In the end, we are left with his observation that it takes a long time and great effort to overcome long-standing problems. One of the most moving passages for me is his description of what he was thinking about on his first trip to India. It deserves mentioning as we try to anticipate what Joe Biden may be able to accomplish against Trump’s continuing resistance.

The short form of the story is that by the end of his first two years in office when Democrats gave up over sixty seats and control of the House, Obama had the scars to prove that blocking change and the establishment of social justice is much easier than fostering “real change” that seeks social justice. Positive messages often lead to election or fame, but not necessarily to change. The road to real change may seem like a superhighway while getting elected, but the grade toward “a promised land” gets steep immediately after the election, and in a very short time the road narrows to a path that would be a challenge for a mountain goat.

Let me lavish a little of Obama’s rich prose on you. On page 598 he writes:

I’D NEVER BEEN to India before, but the country had always held a special place in my imagination. Maybe it was its sheer size, with one-sixth of the world’s population, an estimated two thousand distinct ethnic groups, and more than seven hundred languages spoken. Maybe it was because I’d spent a part of my childhood in Indonesia…or because of my interest in eastern religions, or because of a group of Pakistani and Indian college friends who taught me how to cook dahl and keema and turned me on to Bollywood movies.

More than anything, though, my fascination with India had to do with Mahatma Gandhi. Along with Lincoln, King, and Mandela, Gandhi had profoundly influenced my thinking. As a young man, I’d studied his writings and found him giving voice to some of my deepest instincts. His…devotion to truth, and the power of nonviolent resistance to stir the conscience; his insistence on our common humanity and the essential oneness of all religions; and his belief in every society’s obligation, through its political, economic, and social arrangements to recognize the equal worth and dignity of all people–each of these ideas resonated with me.

His list of hope givers who dealt with a long wait and disappointment with whom he associates himself should include Frederick Douglass. Perhaps he knows that like President Trump, many Americans would not know who Douglass was, when he lived, or what he tried to accomplish. The most significant unifying concept on the list is not that each of these individuals tried to expand human rights, which is true, but that each of them met enormous resistance over long periods of time and at the time of their death the goals to which they had dedicated a lifetime of work and thought were still not realized.

Joe faces resistance from Republicans on his right and the potential for constant harassment from progressives on his left who are likely to claim that is moving too slow, setting the wrong objectives, and selling out to achieve small victories that are examples of a lack of will. Obama is clear about the fact that he was as harassed from the left as much as he was from the right.

Obama continues:

Gandhi’s actions had stirred me even more than his words; he’d put his beliefs to the test by risking his life, going to prison, and throwing himself fully into the struggles of the people. His nonviolent campaign for Indian independence from Britain, which began in 1915 and continued for more than thirty years, hadn’t just helped to overcome an empire and liberate much of the subcontinent, it had set off a moral charge that pulsed around the globe. It became a beacon for other dispossessed, marginalized groups–including Black Americans in the Jim Crow South–intent on securing their freedom.

Obama’s narrative continues as he describes the visit that he and Michelle made to Gandhi’s home in Mumbai. For him it was the equivalent of visiting a religious shrine. As he stood in the modest room where Gandhi had lived, slept and written, he reflected on Gandhi’s assasination by a religious zealot in 1948, and the disappointment that Gandhi must have experienced about the incompleteness of the work he had started. He wished that he could talk with Gandhi:

…I had the strongest wish to sit beside him and talk. To ask him where he’d found the strength and imagination to do so much with so very little. To ask how he’d recovered from disappointment.

He’d had more than his share. For all his extraordinary gifts, Gandhi hadn’t been able to heal the subcontinent’s deep religious schisms…Despite his labors, he hadn’t undone India’s stifling caste system. Somehow though, he’d marched, fasted, and preached well into his seventies–until the final day in 1948 , when on his way to prayer, he was shot at point blank range by a young Hindu extremist who viewed his ecuimenism as a betrayal of the faith.

Unlike Gandhi, King, and Lincoln, Obama was not shot, although a sense of that possibility was a constant presence. There are crazy people in the world and it appears that for the near future at least, there will be someone whose rhetoric could ultimately make anyone who tries to lead us toward a more just and humane nation a target. Sadly, we have seen violence against great leaders before.

The papers are full of columnists trying to explain this moment to us and present the options that Biden could consider. In the end, it is a discussion of what strategies are most likely to allow progress toward objectives like universal healthcare access, diminishing inequality, and improving the social determinants of health, all of which must be accomplished against the certain resistance from the economic interests of the status quo.

I liked the advice that E.J. Dionne gave Biden in his column in The Washington Post earlier this week, entitled “How Biden can make us hate each other a little bit less.” The same piece was reprinted in my local paper today with the title “Can Biden find harmony in our dissonance?” Perhaps the first title was just a little too raw for the season of peace, joy, love, and hope. The sum total of Dionne’s argument, which is borne out by the passage today of a bipartisan, but totally inadequate second bill to offer relief from the economic consequences of the pandemic, is that little bits and pieces of progress will represent monumental accomplishments and will happen only if Biden performs flawlessly. He begins by talking about the amazing popularity of John Lynch, a New Hampshire governor who enjoyed a popularity rating of 73%.

There is an obsession in our deeply polarized country with how we might come together. Many of the popular remedies are of a touchy-feely sort: Listen to each other better, spend time with people we disagree with, read those whose views differ from our own.

All are virtuous activities, but our polarization is about more than sentiments. And as a practical matter, a president operating in a climate of exceptional partisan mistrust — especially one confronting a Republican Party that resisted even acknowledging that he won the election— can never achieve what Lynch did.

As bad as it is, Dionne thinks Joe has the skill to lower the “political temperature a few degrees.”But there are a few if’s:

First, though, he should forget about making everybody happy. Any president who stands for something will incur the disapproval of at least a third of the people. This group will include old-fashioned partisans who, in Biden’s case, will never like a Democratic president, and a subset of Trump extremists who will forever regard his presidency as illegitimate.

That crowd will make a lot of noise. Biden and his aides will need to persuade the country — and especially the media — that the haters and online ranters do not represent “the voice of the people.” They are a minority that will never be reconciled to his presidency.

Second, Dionne advises Biden to pick his battles. This was a recurrent theme in Obama’s presidency. Obama admits that it will be decades before historians decide whether he ever had a chance or if he blew his chance for slow progress by pushing hard, and losing a lot of political capital on an aggressive progressive agenda during his first two years in office.

The fights he chooses to pick with Republicans should be on behalf of proposals (a higher minimum wage, affordable health insurance, more family-friendly workplaces, political reform to reduce big money’s role in politics) that make clear who is on the side of the forgotten.

This also means that Biden’s laudable emphasis on fighting climate change must constantly come back to the job-creating potential of investments in green technologies — which is what Biden did when he announced his climate team on Saturday. The surest way to block progress is to allow opponents of climate action to cast it as a war by “elitist” environmentalists on workers employed in existing energy sectors.

Success requires speaking to the needs and attitudes of working-class White voters while not disappointing the Black voters who put him in office, or turning the impatient progressive left against him. The far left is just as inclined as the far right is to use any tactic possible to force the outcome they want. Biden will never satisfy either end of the spectrum, but Dionne is advising him that slow progress toward an America that most of us want is possible, but the emphasis is on slow. As the Johnny Cash song suggests, you can get what you want if you are patient enough to acquire your dream “One Piece At A Time.”

Dionne is one of a small group of commentators who addresses the fact that all that divides us includes more than race and economics. Much of the strife and animosity arises from our “culture wars.” It was culture more than economics or race that made me feel uncomfortable as I drove my RV across the “red states” that lie in the middle of this very wide continent.

The larger lesson is that culture wars are at the heart of our polarization. If they become ferocious, they will block Biden’s efforts to broaden his reach. As a religious person, Biden — simply by virtue of who he is — can reduce levels of mistrust bred by the growing secular/religious divide, and he needs to handle church/state questions with care. He has a moral obligation to be uncompromising on issues of racial justice, but advocates of change need to find arguments (and, yes, slogans) that appeal across existing lines of division.

We should never give up the progressive dreams of Obama, Lincoln, King, Mandela, and Gandhi, but we should also remember that progress requires empathy and patience. Dione is hopeful, but hope needs experience, forethought, resolve, and a plan—and as a catalyst someone who is an incrementalist at heart with at least 47 years of experience.

There is, unfortunately, no vaccine that can bring a sudden end to polarization. But with care, attention and shrewdness, Biden has a chance to give himself room to govern by making us hate each other a little bit less.

I would like to think that we can maintain hope that this time next year someplace on the list of “21 Good Things That Happened In 2021,” we will find something like, “Joe Biden used his political skills and great empathy to bring us a little closer together.”