Lean is my favorite flavor of continuous improvement. I see Lean to be a term like “jazz” that defines an evolving philosophy that thrives on innovation. Lean is to continuous improvement as jazz is to music. Jazz is a continuously evolving art form that allows individual expression within the context of a structure. Lean encourages individual participation within an organizational atmosphere of respect and commitment to the elimination of waste.

On introduction to Lean there are basic principles and tools to be mastered, just as a fledgling musician should master an instrument and become familiar with the classical scales. The basics of Lean can be traced back to the emergence of the scientific method, but its future resides in its power to draw productivity and improvement out of the chaos of complexity.

It has been said that you can learn the rules of backgammon and be playing the game in less than thirty minutes but it takes a lifetime to master the game. Thirty minutes into your first RIE you will be “doing Lean” but years later you will still be having new Lean insights and a growing understanding of the power of the philosophy and culture that Lean spawns.

In the nineteenth century Ernst Haeckel made the debatable proclamation that “ontogeny recapitulates philology”. There is a certain poetry and symmetry in that this little bit of exaggeration. It roughly translates as: the development of the individual (ontogeny) follows the path that its ancestors traveled (phylogeny) throughout evolution. Does this concept also suggest that organizations, industries and societies progress through a series of transformational steps? I think so.

One of my fascinations with the creation narrative of Apple is its evolution from a “garage adventure” of two adolescents to become one of the world’s most creative organizations. All along the way, ontogeny was recapitulating philology. The history of my own organization of origin, the Harvard Community Health Plan, is another confirmation that organizations and social structures seem to follow a path of developmental stages from foundational ideas to complex structures that is reminiscent of the path of the growing embryo and child as it moves toward maturity and sustainability.

Why is it that the higher people rise in any structure the more vulnerable they feel, if they ask for or accept the input of others? If you enjoyed the allegorical and compressed presentation of Apple as shaped by the genius and character flaws of Steve Jobs and witnessed the dramatization of the relationship between Steve Jobs and his cofounder Steve Wozniak in the recent movie where Michael Fassbender played Jobs, you saw this dynamic again and again. It was beyond the ability of a two-hour movie to present how Jobs was transformed after failing and being fired, and how he learned to be successful with a different leadership style and a more respectful relationship with the people at Pixar. After his transformation, Jobs returned to Apple with a new collaborative leadership style that enabled him to lead Jony Ive and others to greatness.

Before I became a board chair or a CEO and even long before my experience as a physician leader, I was trapped in a dysfunctional set of concepts about leadership. My distorted concepts of leadership were right out of what social historians would call the “big man” concept. I did not recognize that there were other examples of leadership like the one offered by Gandhi. He famously said, “You have to be the change that you want to see in the world”.

The “big man” leadership concept remains a primal urge that is hard for us to discard, as we are reminded as we suffer through this year’s process of choosing a new president. The search for the right “big man” is different this year only in that one of the candidates for “big man” is a woman and that many of the self appointed candidates are willing to disregard civility and appeal to the darkest components of fear and self interest as they make the case for why they should be the next “big man”.

My first exposure to a variation on the “big man” theme was a presentation of situational leadership, a philosophy that was gaining acceptance in the late seventies and early eighties when I was first exposed to it. Situational leadership suggests that different moments demand different leadership styles and that you can change your leadership style like you change your clothes. Which “leadership suit” to put on is circumstantial and depends on the situation as described by who the followers are and what the situation is. Sometimes one should be directive, at other times collaborative. To be facetious, you do not wear a tux to a cookout or Bermuda shorts to a formal event. The concept was interesting but felt manipulative and more like acting than leading. I continued to be myself with mixed results.

The next big experience for me was the exposure to the leadership work of Jim Collins as presented in Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap…and Others Don’t. The structured levels of leadership culminating in “Level Five Leadership” appealed to me. Collins’ description of leadership seemed to ask a spiritual question: Is a level 5 leader an example of a “servant leader”?. Reading Collins was the first step in a process of personal transformation. His work presented many “threads” that I began to follow simultaneously with the ideas of the quality and safety movement.

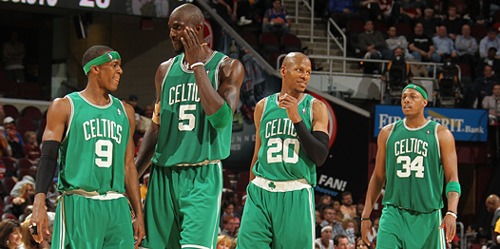

My new responsibilities as CEO coincided with a remarkable event, the resurgence of the Boston Celtics! Coach “Doc” Rivers had a core group of veterans who were all looking for a championship that had eluded them through otherwise illustrious individual careers. They built a championship team around the concept of “ubuntu”. If you followed the last link you read the players talking about ubuntu. Perhaps Desmond Tutu can give us a broader appreciation for this philosophy that is counter to self-interest.

Bishop Tutu… Ubuntu is the essence of being a person. It means that we are people through other people. We can’t be fully human alone. We are made for interdependence, we are made for family. Indeed, my humanity is caught up in your humanity, and when your humanity is enhanced mine is enhanced as well. Likewise, when you are dehumanized, inexorably, I am dehumanized as well. As an individual, when you have Ubuntu, you embrace others. You are generous, compassionate. If the world had more Ubuntu, we would not have war. We would not have this huge gap between the rich and the poor…This is God’s dream.

Not long after I began to contemplate ubuntu, and was asking myself how its philosophy fit with the lessons that I had failed to incorporate into my concepts of leadership, I was exposed to Lean for the first time and like a lot of other novices did not recognize that it was more than tools. Not long after we began “doing” Lean I attended some seminars at MIT’s Sloan School. There I was surprised by an introduction to yet another facet of leadership that I was not expecting. The speaker was Professor John van Maanen whose work in organizational behavior focuses on organizational ethnography and especially the tension between an organization’s formal leadership and its informal leaders. In the course of his discussion, he threw out the term, VUCA. VUCA as Professor van Maanen defined the acronym so fascinated me that I began to do some reading on my own which took me to Bob Johansen’s book, Leaders Make the Future: Ten New Leadership Skills for an Uncertain World.

Those new skills which Johansen described included activities such as rapid prototyping and crowdsourcing and seemed totally aligned with the thinking of Collins, his teacher, Peter Drucker, Charles Handy, Desmond Tutu and Doc Rivers and all that I was beginning to learn about leading in a Lean environment. The pieces of the picture of the leader that I wanted to try to be were coming together. As a picture of the deep personal transformation that would be required of me was coming into focus, I did not know that there was more to come.

When I first read Accountable Care Organizations: Your Guide to Strategy, Design and Implementation published in 2011 by my friend and former colleague, Marc Bard and his colleague Mike Nugent, I was captivated by Chapter Five, “Accountable Care Sociology”. That sounds pretty dry but the core lesson for me was the amalgamation of ubuntu, the motivation for continuous improvement, and managing the complexity and uncertainty of a volatile and ambiguous medical environment. The authors pointed out that it was necessary to our mission (for me the Triple Aim) for clinicians to move from their historical mindset of “I am accountable” to a new position, “we are accountable”.

At that moment I realized that servant leadership, level five leadership, ubuntu, management skills for an uncertain future, and “I to We” all came together in the standard work of a Lean leader. It was also clear that if I was to be true to my responsibility, I had to continue on a course of self discovery and personal learning and transformation even as I was expecting, even demanding, that others individually and collectively change.

John Toussaint wrote about the importance of leadership, Lean Leadership, in his most recent book: Management on the Mend: The Healthcare Executive Guide to System Transformation.

After more than 145 such visits in 15 countries [visits to organizations that are practicing Lean]…I understand why I am seeing hope and failure in nearly equal measure. Teams of clinicians and administrators using lean thinking are making breakthroughs every week as they increase quality and reduce costs. But the essential transformation of the organization is not happening due to some basic misunderstandings about lean in healthcare.

Then he wrote:

The most common problem I see is that leaders fail to recognize the magnitude of change that will be required and that change extends to the leaders on a personal level... lean healthcare is not an improvement program. It is an operating system that requires a complete cultural transformation…

Dr. Toussaint continues with a description of the role of the CEO that is about as far as you can get from “big man” management. Failure can arise from many sources. Lean failures often come from what you do not know that you do not know. Many CEOs who think their organizations are doing Lean do not realize that their organization is actually on a road to failure because they are not performing their role. It is painful to know that many people within organizations that are “doing Lean” realize that they could do more if their CEO and other senior managers would realize that success requires senior leadership “be the change that they want to see”.

Lean can enter an organization at any level of the structure, but it will not succeed without the transformation of senior leadership that Dr. Toussaint has deemed to be necessary. Leadership transformation is fundamental as the precursor of the creation of a culture where Lean can thrive. Senior leadership often introduces Lean and then abandons it to other managers or consultants and then goes back to their previous top down habit of “managing by objective” rather than leading their people to understand “management by process”. Sometimes Lean enters an organization through middle management and a transformation occurs in one process but is limited from further spread until senior management becomes convinced that Lean is the operating system that is most compatible with solving the problems of the future that challenge the mission and sustainability of the enterprise.

In the weeks that follow I hope to give you a closer look at Lean leadership and then expand the discussion to present how Lean culture can be fostered as the foundation of a healthcare organization that dreams of advancing the Triple Aim.