I have a confession. For some time I have had the suspicion that the idea of the Triple Aim does not effectively call many of us or our institutions to immediate action. I hear an occasional doctor or administrator talk about the “Quadruple Aim” and that makes me even more skeptical. I can understand attaching the desire of making a career in healthcare survivable to the concept of the Triple Aim, but I still prefer the focus on the patient, the health of the community, and the cost of care as the primary focus of our attempts to improve healthcare.

I have felt that even before the pandemic dominated our world, our concern with the cost of care, the racial, economic, and class inequities in care delivery, and healthcare disparities that result in great variation in life expectancy that persists between poor and wealthy communities had lost some momentum or had stagnated. I had begun to wonder if perhaps Berwick, Nolan, and Whittington should have named their idea the “Triple Dream.” Compared to what we see in the real world what they presented as plausible seems like a utopian dream. Martin Luther King, Jr. was being more realistic and poetic back in 1963 when he described his vision of equality, justice, and racial harmony as a dream rather than an aim or goal. Dreams can persist without question indefinitely. When “aims” have not been met in more than a decade and enthusiasm for the challenge seems to be in decline it is easy to become cynical about the prospect of ever achieving the goal that the aim describes.

Even though I have been filled with doubt about the possibility of something like the Triple Aim occurring in my lifetime I am committed to the dream of improving the care for the individual, improving the health of the community, and improving the efficiency of the care for individuals and communities enough to eliminate waste and make the cost of healthcare sustainable. I do believe in the wisdom of supporting professionals to have a meaningful professional experience that is the sentiment of those who call for a Quadruple Aim, but in the real world where we live with a focus on finance, their goal of a more tolerable workplace is also more of a dream than a proximate possibility. It just seems likely that the Triple Aim is such an elusive goal that adding another objective moves the benefit to patients and the community that is the basis of the Triple Aim even further away. The Triple Aim, or if you prefer, the Quadruple Aim, seems to have become the medical equivalent of “cold fusion,” Both represent things that would be wonderful, but many don’t believe they will see either in their lifetime and more importantly are not committed to making the changes that would be required to make such dreams possible.

I have felt less guilty about my lack of faith in the possibility of the Triple Aim because it has been possible to replace it as a central objective with the laudable goal of reducing healthcare disparities. With the pandemic, I have noted that we hear about healthcare disparities and the social determinants of health more often now in the lay press than ever before. I have been encouraged that maybe some improvement is possible because I have reasoned that just admitting, or just noticing, that there are egregious disparities in healthcare, is a necessary prerequisite for even thinking about improvement as a goal. Thinking about why healthcare disparities exist opens the door to other “wicked problems” like poverty, racism, and every other manifestation of inequality.

What has caused the change? No doubt the inequitable impact of the pandemic is an embarrassment to our nation. The pandemic has revealed that “the other America” of poverty that Michael Harrington described in his famous 1962 book with the same name is still with us almost sixty years later. Three generations of children have been born into poverty while we have debated whether the victims of poverty are poor because of their personal failings or whether they were doomed by chance at birth to enter a reality where they never had much of a chance for success. A person who was born into disadvantage in 1962 is likely to have struggled against its awful reality as a child, as a parent, and now as a grandparent. Our debate about the origins of poverty has led to a rapidly swinging pendulum of public policy that will add a program during one administration and then cancel it or undermine it as soon as the other side regains power. The end result is what we see. Poverty is still with us.

The pandemic this year plus the videos of so many Black Americans dying after encounters with the police over traffic violations or potential crimes that were no greater than a misdemeanor has sickened us and made it impossible for most of us to deny that racism still exists as an evil in America. Emmett Till was brutally lynched by a couple of white men when he was 14 in 1955 because he spoke to a white woman. Ahmaud Arbery was lynched in 2020 for the crime of jogging in a white neighborhood. Arbery could have been Till’s grandson. Again, three generations have passed and senseless racial brutality remains as a four-hundred-year-old evil in our midst just as poverty also persists.

Less obvious than the persistence of racial violence from police and a few citizens who want to perpetuate their superiority is the persistence of the little daily stresses in stores, in transit, in schools, on the job, and just while trying to walk down the street that adds stress to the life of a Black American. The constant drip of those little stresses can be the vector for a host of acute and chronic illnesses. The pandemic has shown us that Black and other Americans of color who live in poverty and are often “essential workers” earning a low hourly wage have stress-related chronic diseases plus poor access to healthcare as explanations for why they die more often from infections with the COVID virus.

The pandemic was an add-on to our long struggle with the inequities of race. Those issues would be more than enough to keep us all worried but they are accompanied in our day by other concerns that could alone be singular challenges, not the least of which is our impending climate disaster. Fires in the forests of the West, tornadoes in Middle America, blizzards and cold in the Northeast, and hurricanes and torrential rains in the Southeast would be enough trouble for any time, but in our time they are a warning of more to come that some scientists say our species will not easily survive.

It’s interesting how every “wicked problem” has its deniers. There are those who say the pandemic is a hoax. There are those like Senator Tom Scott of South Carolina who say that we are not a racist country. There are those like our former president who deny that we have a climate problem. The pandemic, the environment, and race all surely contribute to our healthcare problems and move the dream of the Triple Aim further from our reach. The deniers among us make the problems harder to solve, but nothing makes a problem harder to solve than when the solution is perceived as a loss for some controlling interest or as an added burden for some already stressed group like healthcare providers.

I have come to realize that most clinicians are so busy with the challenges of getting through their day that there is little “bandwidth” left for issues that seem to lie outside of the office or the hospital. I have had doctors explicitly tell me that they are not “social workers.” I can understand that a person can be concerned about a societal problem like poverty and even care that it makes their work more difficult and compromises the outcomes of their patient, and at the same time feel that “fixing it” is not their responsibility or even possible if they were to try. It is unfortunate that the scriptures seem to speak to the impossibility of resolving a problem like poverty. A literal interpretation of Mark 14:7 offers either an excuse for not trying to help the poor or it seems to grant us the opportunity to put off the problem to another more convenient time.

For you have the poor with you always, and whenever you wish you may do them good; but Me you do not have always.

I have never felt that this scripture suggested that poverty was such an embedded problem that those in poverty should have their needs neglected. Clinicians through the ages have tried to serve the poor, but going “upstream” to eradicate poverty has rarely been their objective. We have recognized that some of our patients suffer from poverty, racism, poor housing, a lack of education, and all the other factors that shorten their lives but it has not been the objective of most of us to fix the root cause problems. We are happy if we can diminish the damage those social determinants of health cause for a single patient.

Even as we have debated the origins of poverty or the moral responsibilities of healthcare providers and our institutions, a great debate of the last century has been the proper role of government. Leaders like FDR, JFK, LBJ, and Barak Obama have challenged us to use government to improve the lives of every citizen to the greater benefit of the country while others like Richard Nixon, Ronald Regan, Newt Gingrich, and Paul Ryan have argued that government was our problem and could never give us an acceptable solution to complex social problems. There have been others like Dwight Eisenhower, Bill Clinton, and the Bushes who have fallen in between the two poles that define the divide that has stymied us for so long.

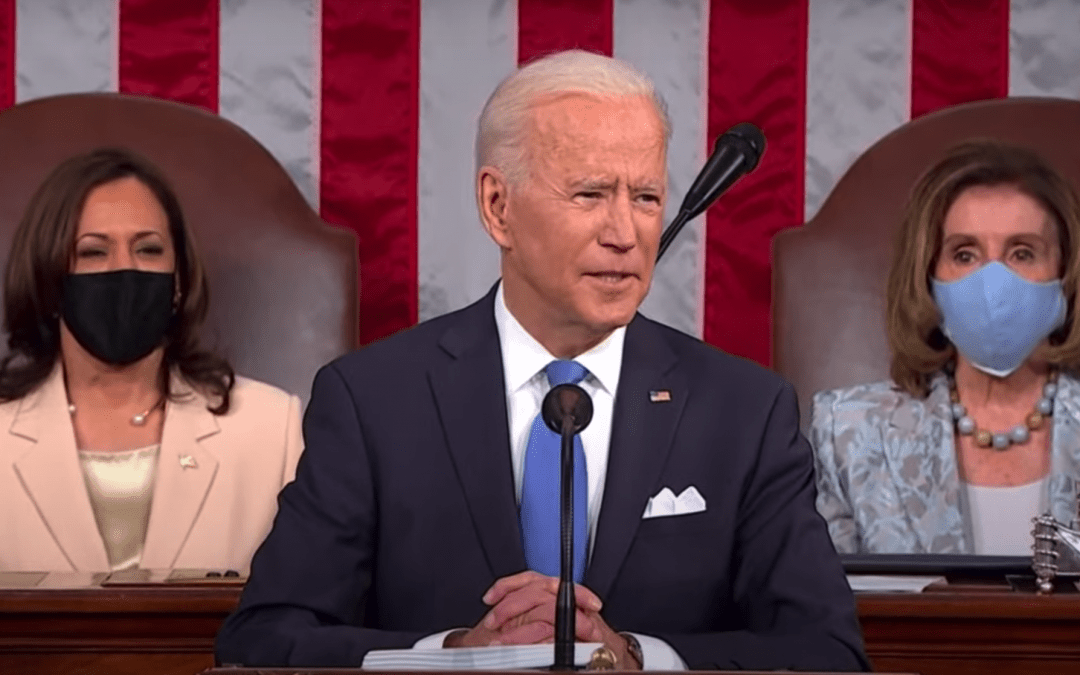

President Biden has surprised many of us. Very few people thought that he would present an agenda for government action to so decisively address the major issues of our day as he did last Wednesday night. Prior to his election, most pundits would have placed him squarely in the middle of the political spectrum. I was surprised because if one considers seriously all that he has proposed against where he appeared to be during the Democratic primaries, the only conclusion must be that he has undergone a rapid transformation and is now espousing a solid progressive agenda that could effectively address what ails us: poor healthcare, a pandemic that threatens the world, unjustified poverty, the persistent sin of racial prejudices with its associated inequalities, and a planet that is nearing a tipping point of environmental disaster. You can read a multitude of surprised columnists in places like The New York Times, The Washington Post, The LA Times, and Vox. Most give his speech a triple-A rating and compare his agenda to the New Deal of FDR, and the Great Society legislation of LBJ.

I was stunned as I tried to imagine what our country could be like if Congress were to send to him for signature the programs and bills that he has proposed. Poverty would be more than halved. We would be taking a huge step toward racial equity and economic opportunity that is color blind. We would be moving in a measurable way toward the end of healthcare disparities by race and class. The objective of improving the social determinants of health would be given a huge boost. We would be on a superhighway to the Triple Aim which would be an achievable goal and not some utopian dream.

The first response is always, “Can we afford to do all of this?” Knowledgeable economists say that we can not afford to not do it. Without actions like the president proposes there will be future pandemics, children will remain hungry, the climate will deteriorate to the point that much of the world is no longer habitable, and we will continue to see the dream of “these truths” fade as we lose our real freedoms to those that believe that the only way to run a world with over seven billion people is with authoritarian principles that favor a few and deny opportunity to many.

So, what will happen? Can Biden’s legislative agenda pass around the objections of an opposing party that believes its most certain path to regaining power is to block all attempts at progress? Ezra Klein thinks that we try too hard to achieve the bipartisan victories that are impossible. In his column written the day after the president’s speech he writes:

The legislation Senate Democrats have passed and considered in their first 100 days is unusually promising precisely because it has been unusually partisan. They are considering ideas they actually think are right for the country — and popular with voters — as opposed to the narrow set of ideas Republicans might support. The question they will face in the coming months is whether they want to embrace partisan legislating, repeatedly using budget reconciliation and even ridding the Senate of the filibuster, or abandon their agenda and leave the rest of the country’s problems unsolved.

I don’t know what will happen, but I do pray that we will give Joe Biden the chance to give to us a few programs in the spirit of the New Deal and the Great Society. Social Security and Medicare were the product of those partisan ideas, and as Klein points out, in time they gained bipartisan support and became an accepted part of our society because they did work and do prove that government can improve the lives of all Americans. I think we can do it again. Maybe a few dreams will come true.