Much has been written in recent years about medicine and the physician…A cursory survey of what has been written…permits the conclusion that medical science comes off rather well and the doctor’s image not so well. One gains the impression that doctors as a group are motivated by money, are becoming less and less interested in patients as people, and are socially irresponsible.

I have lifted those words from the Kate McMahon Lecture that Dr. Robert Ebert, then the Dean of Harvard Medical School, delivered at Simmons College in October 1967. The lecture was a summary of his concerns, and a snapshot of healthcare as it was. Dr. Ebert thought that we were misusing hospitals, not properly educating the next generation of physicians for the real challenges that faced our society, neglecting primary care in general, and failing to deliver adequate care to the rural and urban poor. If you have the time, it’s worth the effort to read it because it underlines the reality that the more things seem to change, the more they are really the same.

He goes on to say:

The public has been indoctrinated to believe in the miracles of modern medical science, but the reality of delivery falls short of the expectation. The doctor is uneasy because his traditional role seems to be changing. He can no longer act solely as an individual, for he has become increasingly dependent upon others…This changing role is related to his changing social responsibility and he is ill-prepared for the change.

Is he reading our mail? The next thought worth your attention is an expression of a tradition that has faded over the intervening half century. Many of us have never experienced the sort of “giving” that was a charitable manifestation of professional responsibility. I for one do not mourn the loss of the “charity” patient and pro bono practice. It may have made doctors feel as if they were “giving” to the community, but that sort of practice was a “band aid” and a poor management system through which to deliver quality care, especially for chronic disease management. His words suggest that doctors were dealing with “adaptive change.”

There are two other traditional ways in which the physician has sought to discharge his social responsibility. The first is by the provision of free care to the poor; the second is by teaching without financial reward. But these roles are also changing, and part of the modern physician’s dilemma is the impending loss of this highly personal kind of giving.

I never knew Dr. Ebert to go through a description of a problem without drawing a conclusion. I have bolded important points here and later for emphasis.

There is no lack of problems to preoccupy the physicians who wish satisfaction from personal involvement in the health field. In my opinion the social problems are of greater magnitude than those which are strictly medical. Not only is there a place for the physician in the approach to these problems but he must be involved if they are to be solved.

Dr. Ebert is calling individual physicians to a leadership role in the resolution of the inequities in the social determinants of health. He moves on to discussing the history of hospital care and the reality that existed in 1967. What he describes may feel much like the dynamics that you experience in the hospital today.

Most physicians look upon the administrative staff as the housekeepers, the board of trustees as money-raisers, and the medical staff as the permanent, rent-free tenants of the hospital. The result of this divisive organization is an institution singularly handicapped in planning for the health care of the community which it serves.

After discussing how the hospital and physicians have their separate agendas and are continuing with an uneasy detente, Ebert focuses on two populations that have been ignored as hospitals and physicians continue to vie for primacy. These populations remain vulnerable today:

There are two groups who have suffered from the changing pattern of medical practice: the rural population and the urban population occupying the central city. Both groups present special problems, and both require new approaches to solutions…The central city presents a different problem [from those of the rural poor] and one of greater magnitude…The city or county hospital or large urban voluntary hospital provides most of the care for the urban poor. Often the actual medical care is good, particularly for the acutely ill patient, but too often it is care without dignity. Service is frequently fragmented among different hospitals for members of the same family, and even when paid for it tends to retain the trappings of charity.

What follows in his speech is truly remarkable when you consider that he was talking just after The first Federally Qualified Community Health Center had just opened a few miles away at Columbia Point.

First, the health problems of the urban poor are intimately linked with their socio-economic problems, and they cannot be solved by imitating the care given in the suburbs.

Second, more than the physician alone is required to provide these services; a well-organized team is essential.

Third, the community itself profits from a sense of active participation in the project.

These are important lessons, and the physician can display a new kind of social responsibility in contributing to the solution of the problems of urban health.

Again, Dr. Ebert describes a problem and offers solutions to consider that demonstrate deep thought about issues that go far beyond running Harvard Medical School as one of the world’s premier teaching and research institutions. What follows is a description of “the medical home” before we had the name.

The provision of medical care in the rural community and in the central city will require a different kind of organization of medical resources than has existed in the past. The physician must learn to work more closely with social workers, nurses, visiting nurses, in fact all of the members of the health professions. There must be a sensible division of labor so that the physician performs those services which only he can do, and other duties are delegated to appropriate members of the health team… This is not an easy problem for it will be necessary to make the most efficient use of expensive manpower and still maintain the personal nature of medical care. I believe this can be done but it will take innovation and will require of the physician a new kind of responsible social action. Care for the chronically ill and for the elderly, who so often suffer from chronic disease, is a particular case in point. Chronic illness is increasingly common and it cannot be handled effectively if it is thought of as an exclusively medical problem. The social, emotional and economic impacts of chronic disease must be understood and intelligently dealt with. Here the physician must share the responsibility with others who have special skills to offer.

Again I point out that he is speaking in 1967 about team based care, innovation to improve care delivery, and sensitivity to the social, emotional and economic impacts of chronic disease. The physicians must “share the responsibility with others who have special skills to offer” and work at the top of their licenses. Dr. Ebert was prescient. He knew that the challenges of caring equitably for the underserved would require physician led practice transformation.

I do not think it is an unrealistic leap from the attitude and principles that he articulated on that October day so many years ago to the work of today’s IHI. He founded Harvard Community Health Plan as a learning lab to test many of his ideas. He was a man of vision and hope.

President Obama was elected in 2008 because he was offering hope, not fear. He wanted to be a uniter and not a divider. Perhaps in fifty years we will have a better perspective on what he was able to accomplish against incredible resistance. I doubt that fifty years from now anyone will question his idealism or his vision for a united America that recognized the necessity of equitable universal health care as a foundational requirement for any durable and successful modern society.

I signed on to his vision of hope when he spoke at the 2004 Democratic Convention, and now I grieve over the way in which we wasted his genius. I can get choked up just thinking about his spontaneous singing of “Amazing Grace” after the tragedy in Charleston.

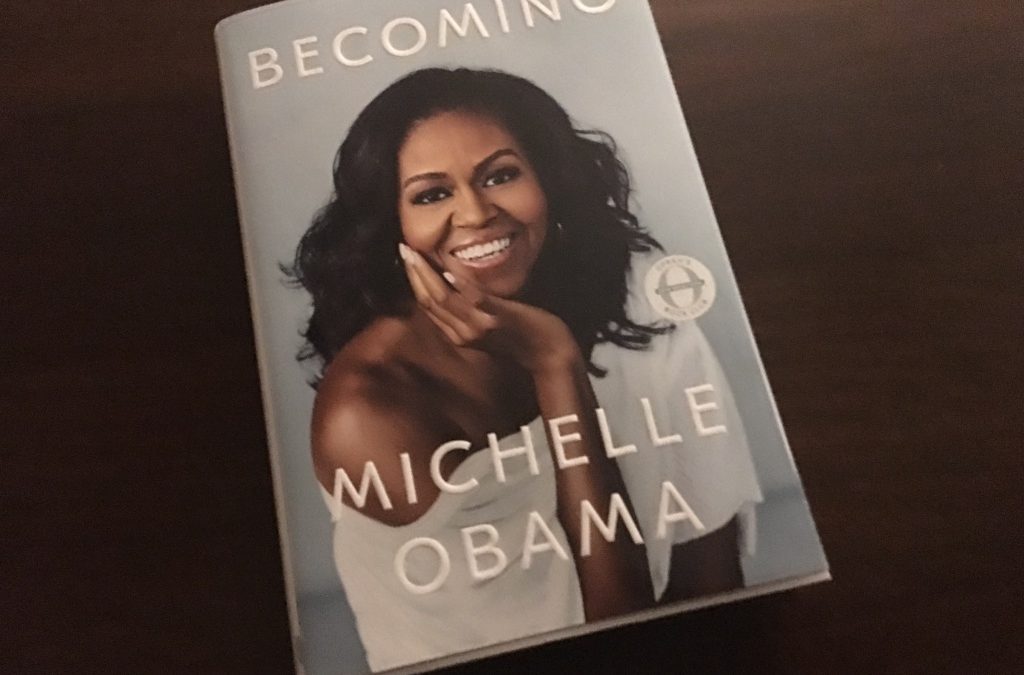

You would not be surprised to learn that I preordered Michelle Obama’s autobiography and have been reading it since it came out last week. The book has surprised me because I did not expect it to provide me with so much new information about my hero. I have really enjoyed viewing the president through the eyes of his wife. He was talking about economic inequality with her before their first date. She presents a man who never questioned his responsibility to use his immense talents for the improvement of the community. What surprised me most was her own similar ideals and how she had to modify her own mission to accommodate his destiny.

From the moment Michelle Obama left Harvard Law School for a great opportunity at a prominent law firm in downtown Chicago she was questioning whether she was doing what she should be doing. It is good that she was there for awhile because that is where she met the future president when he did a summer internship. Over the next several years she moved from the law firm to jobs that did not pay well but were much more satisfying before finding her perfect job in healthcare working for the President of the University of Chicago Medical Center developing community outreach programs for the underserved. She loved the work and reluctantly gave it up for the long campaign process that culminated in her husband’s election as president.

What she writes reminded me of Dr.Ebert’s concerns in 1967 and underlines her husband’s commitment to improving access to affordable care.

Finally, there was the issue of people desperately needing care. The South Side had just over a million residents and a dearth of medical providers, not to mention a population that was disproportionately affected by the kinds of chronic conditions that tend to afflict the poor–asthma, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease. With huge numbers of people uninsured and many others dependent on Medicaid, patients regularly jammed the university hospital’s emergency room, often seeking what amounted to routine nonemergency treatment or having gone so long without preventative care that they were now in dire need of help. The problem was glaring, expensive, inefficient, and stressful for everyone involved. ER visits did little to improve anyone’s long-term health, either. Trying to address this problem became an important focus for me. Among other things, we began hiring and training patient advocates–friendly, helpful local people, generally–who could sit with patients in the ER, helping them set up follow-up appointments at community health centers and educating them on where they could go to get decent and affordable regular care.

She was a committed healthcare professional who understood the challenges of the urban poor. She understood the importance of good diet to health and championed good nutrition and concerns about childhood obesity as the first lady. Her concerns for all children were triggered by her daughter’s pediatrician warning that she was at risk for a lifetime of chronic because she was becoming overweight. Based on her description of her own values and commitment I am certain that the former first lady and former president will find ways to continue to contribute ideas and efforts to improve the health of the nation. They know that we know a lot about the effective treatment of disease. They also know that we still do not know how to equitably distribute what we know and should provide for everyone.