It is easy to talk about the disparities in healthcare, but making progress against the current of complex social issues that are at the root of the differences in care experience and outcomes between populations has proven to be very hard. We have preferred “military language” as we have divided the problem into smaller issues that contribute to the disparities in experience into various “wars”, “struggles”, “fights” and campaigns”. President Johnson sent us to “war” against poverty. President Nixon announced the “war” on drugs. The “struggle” for civil rights has been in progress in one form or another since the mid nineteenth century. That fight continues today under the banner of Black Lives Matter in the pushback against violent police actions that disproportionately harm black Americans. There are fights for equality for women as well as for the LGBT community. To all of these established “wars” we now have a war on income inequality. In their sum these “wars” and “fights” are still only a part of the totality of the problem of disparities in healthcare. To them we must add unequal educational opportunity, poor housing and homelessness, unemployment, child abuse and other continuing concerns, if we are ever going to fully understand why it is so hard to overcome disparities in healthcare and find the equality that is required to achieve the Triple Aim.

Ironically, it seems that progress that has a mitigating effect in any of these areas is then followed by a backlash that can make the next step toward success even harder or seem further away. Ultimate “victory” is elusive. The “wins” of any “battle” remain vulnerable to resurgence and new countering strategies.

The resolution of the complex social problems that work together to create the disparities in healthcare will require highly collaborative and interdependent solutions. The solutions to the problems are often in conflict with the personal interests of individuals. There is no greater tension in our time than the tension between the desires, concerns and fears of the individual and the woes and concerns that we share collectively. Many of us seek refuge and security for ourselves and our families with the false hope that as an individual we can do better than as a part of the collective.

John Lennon’s “Imagine” is definitely on my personal “Top 100” playlist. I do believe that getting to someplace better begins with our “visioning” and imagining the destination. You may reject Lennon’s suggestion that we imagine a world without heaven, hell, religion, possessions and nations but those politics aside, the melody and the words call us to reflect positively on what could be.

My favorite lines are:

Imagine all the people

Living for today…

Nothing to kill or die for

No need for greed or hunger

A brotherhood of man

Living life in peace…

You may say I’m a dreamer

But I’m not the only one

I hope someday you’ll join us

And the world will be as one

Sharing all the world…

I hope someday you’ll join us

And the world will live as one

Heaven, hell, religion, war, greed, an emphasis on possessions, and national interests are still interfering with the world living and sharing as one, now more than thirty five years after Lennon’s death. That world that Lennon imagined probably had no disparities in healthcare that preclude us from realizing the Triple Aim. We have a long way to go to get to our imagined goal. Said another way, we will never have…

Care better than we have ever seen, health better than we have ever known, cost we can all afford, …for every person, every time.

…until we imagine ways to work together to eliminate disparities in healthcare.

I recently attended a fundraiser for the Whittier Street Health Center in Roxbury. For me the peak experience of the evening was a nine minute video that showcased the work of their caring professionals who are doing as much as their resources enable them to make a difference. The video was a call for a renewal of our collective actions to give much more focus to how we eliminate the barriers to health that create a 33 year difference in the life expectancy of someone living in Roxbury compared to their more affluent neighbors less than three miles away in Back Bay.

I wish that the problem was limited to Boston but we all know that inequity in healthcare is our collective dirty little national secret. It is interesting that in Cuba they have a longer life expectancy than we do in America for a fraction of the expense. Their success is built on equity and a strategy that emphasizes the efficiency and effectiveness of primary care and preventative healthcare. In Cuba the life expectancy is almost 80 years everywhere. It makes no difference where you live or what you have. Everybody gets the care they need. In America, life expectancy varies dramatically by neighborhood and by zip code. We have no equity, whether we are looking at the dichotomy of Back Bay compared to Roxbury or the affluent neighborhoods of Houston compared to its notorious “Fifth Ward”. The problem that we name “healthcare discrepancies” is a nationwide collection of complex social problems that are interdependent and will require interdependent solutions everywhere.

John Edwards will be remembered for his expensive haircuts and his controversial private life that took him from the Senate to obscurity by way of a failed presidential bid, but before he flamed out he gave at least one great speech and nailed the concept of “two Americas”. This year’s jousting for the presidency could spawn the concept of multiple Americas. Getting to the bottom of the conversation about the many Americas is beyond my scholarship and would take more words than many multiples of my longest notes, but I do believe the problem is growing. Telling a story may be better than many links to articles on the Internet or references to books you may have no time or interest to peruse.

Recently over lunch with a friend, we were talking about our current activities. My friend asked if I was optimistic about healthcare reform. My first response was to lecture him on the difference between hope and optimism. I then admitted that I thought we still had a very long road ahead of us despite the accomplishments of the ACA. I was surprised to hear myself say that despite my hope, my expectations were that we would not achieve that lofty objective of the Triple Aim in my lifetime. I am impressed with the slow progress in civil rights that has been made in my lifetime. But despite great pieces of powerful legislation and the personal sacrifices of so many people over my seventy plus years, race is still a volatile issue. If the rate of progress in civil rights is my measure, you can see why I do not see the Triple Aim achieved in the few years that I may still have ahead of me despite powerful guides like the IHI and Lean.

Observing the emergence of the “me” generation and the growing bimodal evolution of the multiple Americas makes me skeptical and dampens my hope for a quick move to the Triple Aim. What I see is magnified by the “me” oriented rhetoric of many political candidates. All of our generations are much more focused on self, and it is wrong to place the label of “me generation” on just “gen y” or “millennials”. Daniel Kahneman tells us in Thinking, Fast and Slow, that any time we focus on money we focus on self. He gives just the thought of money or seeing money on a screen saver as examples of the “priming effect”.

The general theme of these findings is that the idea of money primes individualism: a reluctance to be involved with others, to depend on others, or to accept demands from others.

That statement resonates with my experience. If success in healthcare is dependent on collaboration, then nothing kills collaboration like bringing up money. Concerns about money can block the “I to We” transition, or what African tribal theology calls Ubuntu, a concern for community. “I to We” is core to progress toward the Triple Aim. We can never make progress toward the elimination of healthcare discrepancies and the Triple Aim without focusing on community. The increasing complexity and interconnectedness of our greatest challenges are all dependent on collective action and personal or institutional concerns about finance make progress on issues like education, employment, housing, and poverty difficult. Without progress on these shared issues we can forget the Triple Aim.

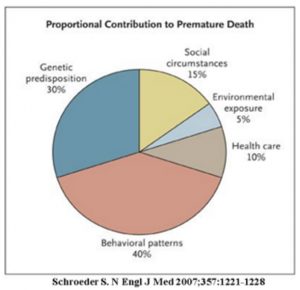

Consider the chart below that shows the proportional contributions to dying before the life expectancy of our country.

This is a composite picture. In the zip codes with health care disparities the pieces of pie that represent social circumstances, poor healthcare, the environment (think lead poisoning in Flint) and behavioral patterns (think depression and substance abuse) are even greater contributors. We have known for sometime that the issues that we note in discussions of income disparity, poor education, poor access to housing and unemployment and lack of opportunity for youth and minorities complicate every issue in our communities. We will not have healthier communities until we address the social determinants of health.

After I had confessed my concerns about the Triple Aim to my friend, I asked him what was up with him. He responded that recently he was working with a foundation that is focused on children and early interventions to overcome the issues that compromise impoverished children. We talked about the importance of the work and it reminded me of an experience early in my years of practice.

Between 1972 and 1979 I worked as a “moonlighter” in the EW of a hospital that sat on the cusp between a post industrial city that was plagued by all of the problems of poverty and a more affluent population in surrounding communities. The differences in the two populations, especially the differences in the children from the two different worlds, fascinated me. The infants and early toddlers were the same no matter what the family’s financial status. By the time the children were in the first grade, there was no problem identifying the children by their population of origin. I began to try to discern what the age was when I could see a difference. I decided that it was when they were between three and four years old. What bothered me then and now is the loss of human potential that seems to occur or be obvious before age five. What bothers me even more are the opinions that I often hear from those with more fortunate backgrounds, as they blame the problem on those who live with social burdens. It makes no sense to blame people for their status when they were born into circumstances that were beyond their control and beyond the control of their parents. The solutions to what we all recognize as huge problems lie in our collective resolve to join forces to confront complicated interdependent problems.

As Berwick, Nolan and Whittington wrote back in 2008 in their article on the Triple Aim, most of us are working on only one leg of the Triple Aim, which is to provide great care to the individual patients who see us. For us to collectively experience the Triple Aim and penetrate those zip codes where people die before their time, we will need to do much more than practice good medicine for our own patients at a sustainable expense. We need to make some changes that require much more than a series of disconnected “wars” or a willingness to make a charitable donation at a fundraiser for a great organization that is struggling to meet the challenges that most of us can ignore most of the time.