September 30, 2022

Dear Interested Readers,

The Data Says There Is Less Poverty, But Poverty Is Still A Huge Barrier To Health

I was pleasantly surprised to hear recently that childhood poverty is down dramatically over the last twenty years. That was the message in a startling New York Times article by Jason DeParle that was published on September 11. Mr. DeParle reports that in 1993 there were almost 20 million children, 28% of all children in America, who were impoverished by the definition of poverty at the time. In 2019, before the pandemic, the official number of children in America who were impoverished was down to about 8.5 million which represented a 59% drop. That was quite an improvement! The number fell steadily during the Clinton, Bush, Obama, and Trump administrations.

We often extrapolate the way we feel in the moment to flavor how we view the past, present, and future, and at the moment we are hearing a lot about rampant inflation, housing shortages, increased crime in the streets, increased deaths from drug overdoses, increased gun violence, and we are concerned about the impact of the pandemic on the education and mental health of children, so to hear that there has been a marked improvement in the poverty statistics for children may seem incredulous. My first reaction to the article before I read it was to remember Mark Twain’s (Samuel Clemons’) witticism that he borrowed from Benjamin Disraeli, that there are lies, damn lies, and statistics.

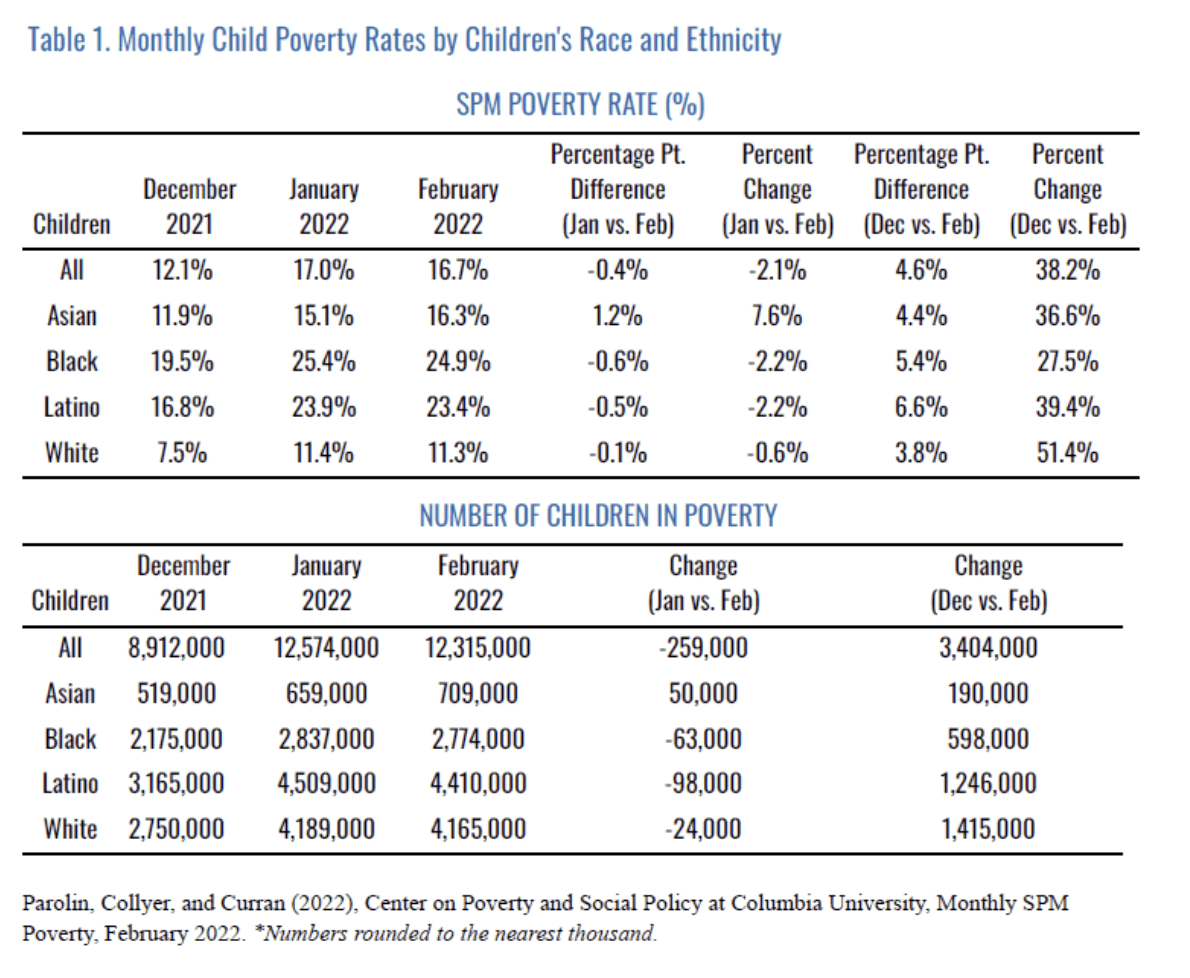

What I learned as I read on were the logical reasons behind the improvement. What I hope to present to you is the vulnerability to the reversal of this improvement and the importance of building on the success that has been achieved. One thing to celebrate is that the improvement has been equitable across all ethnic populations. What is also a reality is that African American and Latinx children are still impoverished disproportionately as the chart below from the Center on Poverty and Social Justice at Columbia University demonstrates. Unfortunately, the report from which that data comes shows that childhood poverty is increasing again since the pandemic child tax credits expired at the end of December 2021.

The data makes sense to me because I saw families that are served by the two charitable non-profits on which I am active and a board member markedly decrease their requests for help during the time they were getting the benefit of the pandemic monthly child payments. I have also seen families fall into significant financial distress when they forgot to renew their SNAP (food stamp) benefits. When you live paycheck to paycheck, small changes in benefits can either put you into a much better situation when income goes up a few hundred dollars a month, or you can sink deeply into distress by a small unexpected bill or the unexpected loss of a small benefit. For years the metric of the number of Americans who could cover an unexpected $400 bill has been an interesting indicator of the vulnerability that the poor in America tolerate. The US Census in 2020 suggested that a little over 11% of Americans lived in poverty. That sounds pretty good but it means that over 30 million Americans are in “poverty.” It is interesting to note that the percentage of Americans who would have difficulty covering an unexpected $400 bill in 2020 was about 35%. Last November it was 35%. In May it was up to 49%.

I should clarify a few points. For the past ten years, the Federal Reserve has been asking about a family’s ability to pay an unexpected $400 bill along with some other questions to try to improve their understanding of how the economy is impacting the financial stability of Americans. Recently, because of the potential for misunderstanding and sensationalism, the question has been asked two ways. They ask if a $400 bill would be difficult to pay or would the individual not be able to find a way to pay. The “can’t pay” number for 2020 was about 12%. The “difficult to pay” number for 2020 was 36%. There are many families who dance back and forth from poverty to solvency from paycheck to paycheck and as a function of random events. Changes in employment, small changes in government help, and unexpected bills or events can put them underwater. Government policies like the pandemic child payments can give them a little relief and small amounts of new monthly cash can lift millions of children and their families out of poverty. I must imagine that something like a universal basic income could reduce stress, improve mental health, and mitigate the social determinants of health. Small experiments in Canada and in Stockton, California as well as our experience with the pandemic child payments have demonstrated that reality.

A life in poverty or on the edge of poverty living paycheck to paycheck and supplemented by government benefits is a life of uncertainty that surely takes a toll on children and their parents. It seems that in 2022 up to 50% of Americans live with this daily uncertainty and vulnerability. In that context is it a surprise that mental health issues are on the rise, as is the number of suicides and drug overdoses?

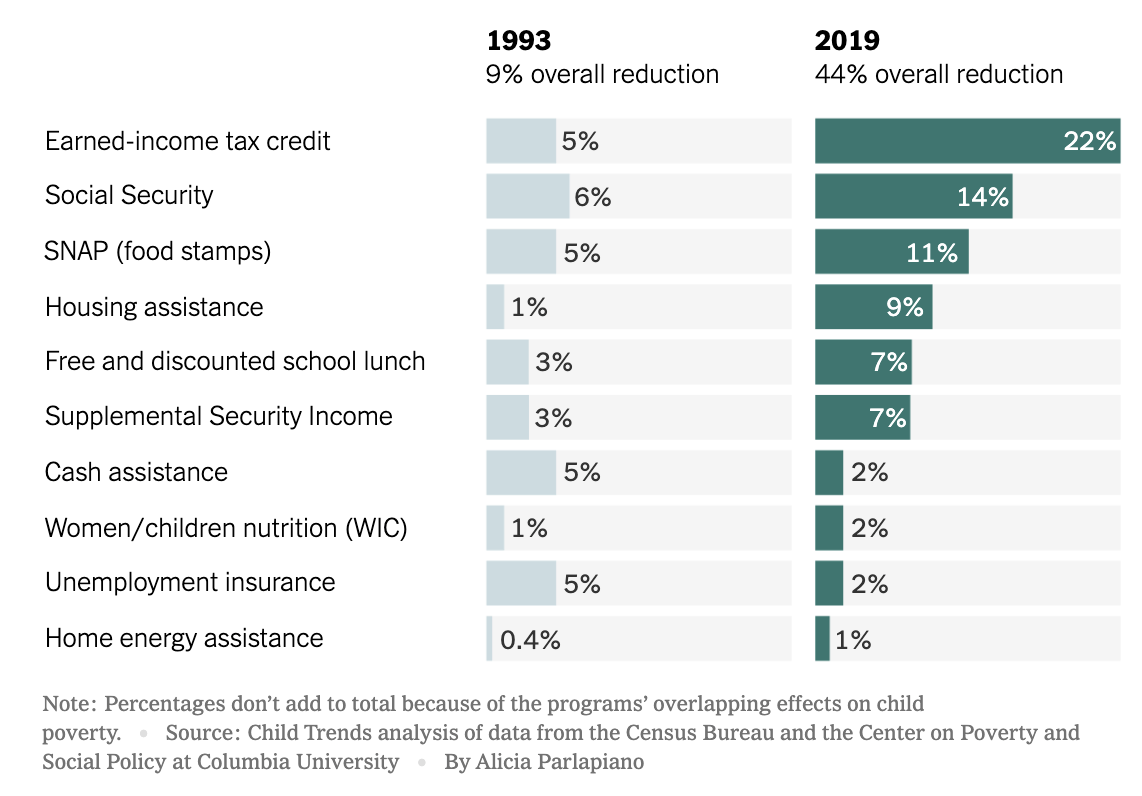

If you read DeParle’s article you will discover that the improvements in child poverty were a function of several moving parts and some shifts in how we measure poverty. 1993 is a good reference point because that was the year that Bill Clinton came to office with the pledge to make welfare reforms that would “end welfare as we have known it.” In August 1996 Clinton signed the “Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act.”

The same month that the welfare bill passed the Clinton-Gore administration published a list of all their accomplishments that shifted the emphasis from paying people not to work toward supplementing the income of the working poor with tax breaks and various forms of direct help. Their list was published in time for the election that year and to claim before the election in November that welfare, as it had been known, had ended. The White House paper celebrates programs like an improved food stamp program, low-income housing assistance, grants for retraining, and other programs that “moved millions from welfare to work.”

DeParle’s analysis is that all of these federal programs have combined in surprising ways to make a difference. My point is that if we have made progress, let’s be sure to continue the efforts that work. It is a shame that the child tax credit passed in response to the pandemic was allowed to expire at the end of 2021. Its renewal along with many other investments in people to give us all a better future would have been included in the passage of President Biden’s American Families Plan and its spin-off Build Back Better Act both of which Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema gutted and no Republican was willing to support.

One point that DeParle makes is that we have made haphazard progress without an overall plan other than to move people from welfare to work. He writes:

Almost every program …examined does more to reduce child poverty than it did a quarter-century ago, either because it raised benefits, expanded eligibility or made it easier to enroll.

But each program expanded in its own way — some by congressional intent (tax credits) and others by demographic change (Social Security) or court order (Supplemental Security Income, which provides disability aid). A primary goal was to help low-wage workers, but there were also major expansions of programs with few if any work rules (SNAP and school meals).

The story of the safety net, in other words, is a story of safety nets — multiple programs with multiple aims, sometimes evolving in uncoordinated or accidental ways.

So we have made progress almost by accident. The overall theme seems to be to incent work or enable people to return to work and then supplement what they make. The problem, it seems to me, is that there is no defined goal and no process in place to effectively focus on what works. It seems to be true that there is a bias against any program that doesn’t have work or the ability to work as an objective. None of the programs are focused on abolishing poverty per se, or reducing the inequities that the system perpetuates from one generation to the next.

Since 1995, Ruby Payne, a teacher, author, and educational consultant has written several books for teachers, politicians, and churches about the cultural aspects of poverty. I don’t agree with everything she has written, but I was impressed by her objective analysis of the barriers that the children in poverty face that compromise their ability to succeed in school and life. She talks about generational and situational poverty. Her analysis is thought-provoking because she is not judgemental and compares the culture of poverty to middle-class and wealthy attitudes. Click here for a downloadable PowerPoint summary of her view of poverty and the impact that poverty has on children and families.

DeParle includes an informative graphic in his New York Times article that shows the relative increase in funding for federal programs since 1993. I would add the ACA and CHIP to the list of programs that have made a huge difference in the lives of those in poverty and those who go in and out of poverty.

Working with families in poverty I have come to appreciate what a full-time endeavor it is to maintain access to these programs. It is very easy to lose SNAP benefits or Medicaid by failing to reregister every six months. The experiences that are related to me by those people I know who are dependent on these programs is that great vigilance is required to maintain eligibility. The bureaucratic complexity may be unavoidable in efforts to prevent abuse, but the “feel” is that there is a counterproductive strategy to limit the utilization of programs. Suffice it to say that there is a great opportunity to improve access to these valuable programs and it is likely that with some effort a more effective strategy of coordination of objectives could occur. It is hard not to be biased against a bureaucracy that seems to be biased against those people they are ostensibly trying to help.

I know at least seven things that are true about the current state of poverty in America. First, no matter how much success has been recorded over the last twenty years we could have done more. Second, all of the programs that have helped could be vulnerable to sudden cancelation for political reasons as we experienced with the very effective pandemic child tax credit. Third, the combination of housing shortages, inflation, and the high cost of gas and heating fuels will push many families who have recently “escaped” poverty back into the economic stress from which they had enjoyed a brief escape. Fourth, poverty remains the most significant negative factor in our analysis of the social determinants of health. Fifth, poverty is a problem across all racial groups, but the percentage of white Americans in poverty is half of the percent of impoverished minorities while many impoverished white Americans continue to be politically aligned against their own best economic interests. Sixth, we will never see health equity as long as we tolerate economic inequities and poverty. Finally, we have the ability to eradicate poverty “as we have known it,” all we need is the will. To add an eighth thing that I hope is true, I believe that someday we will eliminate poverty, and when we do we will ask ourselves how we tolerated its presence as long as we did.

A Different World

Neither my wife nor I remember precisely when or why we decided to book a few days on Block Island during the last week of September. My guess is that we were victims of news programs like CBS Sunday Morning or WCVB’s Chronicle that featured reports about the unique “Glass Float Project.” I think that we saw the beauty of the little island in both presentations, and then asked ourselves, “Why haven’t we ever been to Block Island?” It’s a very good question because my wife grew up in Rhode Island and frequently went fishing and quahogging with her family near Point Judith where one of the ferries to Block Island departs on a regular schedule year-round for the sixteen-mile trip to the little island that takes about an hour.

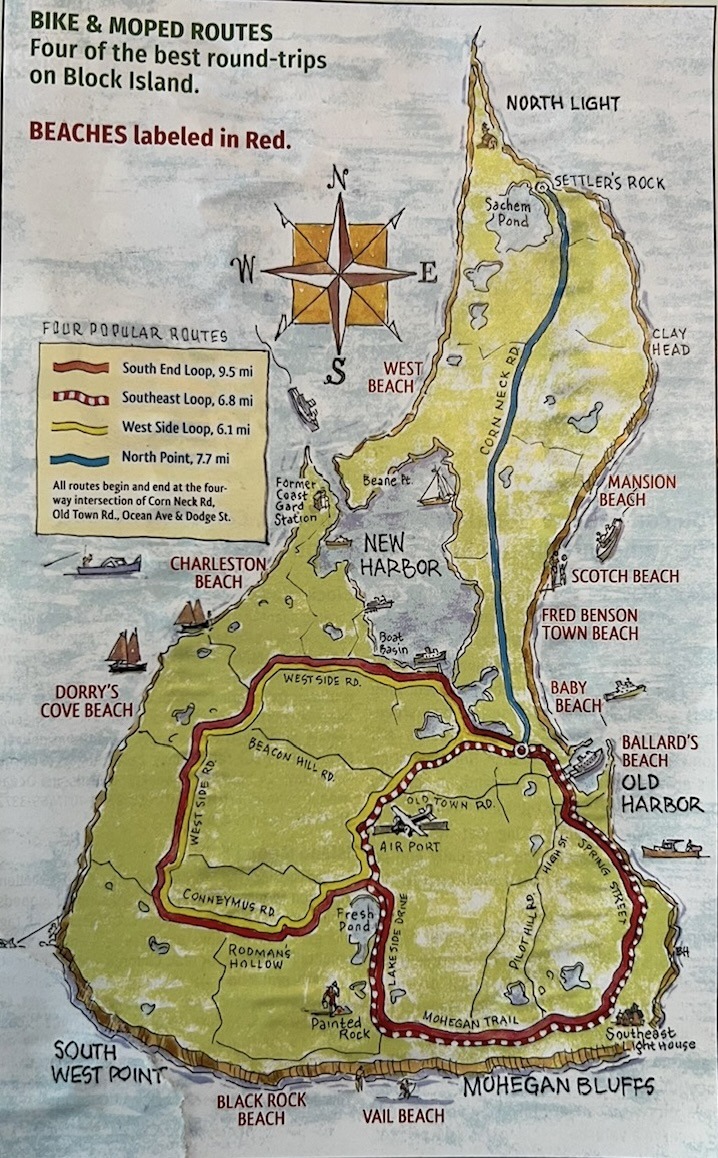

After we decided that we would make the trip, we discovered that our schedule of expected visitors was such that the last week in September was the best time for us to go. The weather was the question for this week. Would there be a hurricane? Would it be too windy or cold? We lucked out. The first hurricane hit Bermuda and passed to the East before we arrived, and Ian, the second hurricane, was far to the South causing problems in Florida while we were enjoying clear skies and temps in the mid-sixties that were perfect for riding bicycles and doing a little hiking. An added bonus is that we had the island to ourselves since the hordes of the summer are gone and the island is in the process of shutting down for the winter. The winter population of this little island which is about seven miles long and five miles wide at its widest point drops to about 1000.

The island, like Marhta’s Vineyard and Nantucket, is a product of the last ice age and its glaciers. The Niantic people, the indigenous people who were the first inhabitants of the little paradise, called the little island “Manisses” which means “little island.” The desk clerk at our hotel told us it really means “heavenly little island.” that name seems appropriate, but a Dutchman named Adriaen Block showed up before the Pilgrims landed in Massachusetts in the early sixteen hundreds and named the little island for himself. We stayed at the Manisses Hotel which is a lovely old structure built in 1876.

Getting to the island was not easy for a couple of septuagenarians. We spent the weekend in Bristol, Rhode Island where we enjoyed riding our bikes on the East Bay Bike Path as a “shakedown” effort before making the crossing. The big question was how to get our backpacks and other gear from the parking lot to the ferry and from the pier on Block island to our hotel. It all worked out fine since it was less than a hundred yards from where we parked to the ferry and only a slightly uphill six-minute walk from the ferry landing to our hotel.

The scenery on the island is spectacular. There are bicyclists everywhere, and not many cars. Almost everything is within a twenty-minute bike ride. It is hilly so I will admit that on occasions I used the “electric assist” of my e-bike, but for much of the time, I did fine without it. I covered all of the recommended “loops” and my wife rose to the occasion and did all but one of the loops.

Since the idea for the trip occurred when we saw the clips about the glass floats, I hope you looked at at least one of the YouTube links from “CBS Sunday Morning” or “Chronicle,” we spent some pleasant hours poking around in an attempt to find one. We did not find a glass orb, but we did find a wonderful place to relax in the midst of inspiring natural beauty. I would recommend that you not wait until you are seventy-seven like I did to make your first trip to Block Island because if you do you won’t have very many years to plan to return on a frequent basis.

A high point of the visit was stopping by Southeast Lighthouse. Several years ago we had seen a report of the move of this 400-ton structure back 300 feet from its original position on the Mohegan Bluffs. It was in danger of falling into the sea since erosion had brought it to within 55 feet of the edge of the cliffs. The header on today’s post shows the eroding Mohegan Bluffs from near where the lighthouse stood before it was moved. Click here to see a beautiful one-minute video of the site and a little of the move that occurred back in 1993. While looking for this clip I discovered that moving lighthouses has become a relatively frequent activity. The lighthouse on Gay Head on Martha’s Vineyard was also moved recently. For one last look at the beauty of the island and the lighthouse, look at this brief video from WCVB’s Chronicle.

I am back at my home in New Hampshire now. It is amazing to see the fall colors that have appeared during the six days of our brief trip to Block Island. We are still a week or so from “peak color,” but the temp dropped into the thirties last night and the next week looks dry so fall is here, and I am getting ready for a spectacular show from mother nature. Wherever you are this weekend, I hope that you will have a chance to relax in the glory of a beautiful fall day.

Be well,

Gene

Hi Gene,

As always – a great article. I so resonated with your comment “Working with families in poverty I have come to appreciate what a full-time endeavor it is to maintain access to these programs”.