September 3, 2021

Dear Interested Readers,

Gawande Delivers Again

I have my healthcare heroes. Most of them like Robert Pearl, Elisabeth Rosenthal, and Zeke Emanuel, I don’t know personally. I just know and appreciate their articles, editorials, and books. There are two of my heroes, Don Berwick, and Atul Gawande, whom I know because we were colleagues at Harvard Community Health Plan or Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates. I am always excited when one of my heroes “speaks,” usually in a book or article. I was delighted last week to see that Atul Gawande had a new article in The New Yorker where he has been writing between books for over twenty years.

If you click on the link above you can review and access all the excellent articles that he has written for The New Yorker going back to the nineties. My three most favorite Gawande articles are “The Cost Conundrum” from 2009, “The Hot Spotters” from 2011, and “Slow Ideas” from 2013. Those are my favorites, but I have enjoyed them all. Who could forget his comparison of organized healthcare to The Cheesecake Factory? Like Don Berwick, Gawande’s lessons for us are always packaged within an interesting story. The August 30 issue of The New Yorker contains his latest story/lesson for us. Gawande introduces us to Dr. Álvaro Salas Chaves of Costa Rica and through the doctor’s personal story he delivers a strong argument for making public health a much more prominent part of healthcare in post-COVID America. Throughout the piece, Gawande refers to the good doctor as “Salas.” Like many of his articles, this one is written from his first-hand experience with his subject. It is journalism at its best. In Lean terms, Gawande always goes to the “Gemba,” the place where things are happening. Gawande visited Costa Rica to see their healthcare system “up close” and “Salas” was his guide.

The article has a long title: “Costa Ricans Live Longer Than Us. What’s the Secret? : We’ve starved our public-health sector. The Costa Rica model demonstrates what happens when you put it first.” If you doubt that recently impoverished Costa Ricans live longer than we do let me direct you to the data. Costa Rica is a small Central American country with amazingly beautiful natural scenery, and about five million citizens. It has the second-highest per capita income in a region where all the countries are poor by our standards. The life expectancy of Costa Ricans in 2019 was 79.8 years compared with 78.6 years for you and me. Gawande’s data is even more dramatic. He reports that the average citizen of Costa Rica has only one-sixth the income of the average American but their life expectancy is pushing eighty-one years and improving while ours has been falling from almost 79 since 2014. In the article Gawande traces the path that Costa Rica followed as it improved its life expectancy for pennies to the dollar compared with our costs from less than sixty years in the 1950s to over eighty years now. As you read the story you will learn that Salas was one of the “Quixotes” who made it happen. Gawande quotes him near the end of the article:

“It is possible to change the picture,” Salas said to me afterward, reflecting on our visits inside the system he’d helped create so long ago. “It is possible to call upon a group of people, a group of Quixotes—do you know Quixote?—who think and can see twenty years, thirty years ahead. It is possible to raise an idea and see it supported by a younger generation to become real.”

Perhaps Gawande is telling us that the greatest difference between Costa Rica and us is not that they don’t have our money and the technology it can buy, but they do have the power of dedicated “Quixotes.” I am getting ahead of myself. There is much to observe before we draw that disappointing and damning conclusion.

If you click on the link above to the article you can either read the story or listen to the article on a leisurely walk of 53 minutes. What follows will not be the story itself but my attempt to deliver to you the insights that Gawande is passing along to us from the story. Gawande’s first observation is obvious but should be stated:

Life expectancy tends to track national income closely. Costa Rica has emerged as an exception…

People who have studied Costa Rica,…have identified what seems to be a key factor in its success: the country has made public health—measures to improve the health of the population as a whole—central to the delivery of medical care. Even in countries with robust universal health care, public health is usually an add-on; the vast majority of spending goes to treat the ailments of individuals. In Costa Rica, though, public health has been a priority for decades.

The covid-19 pandemic has revealed the impoverished state of public health even in affluent countries—and the cost of our neglect. Costa Rica shows what an alternative looks like.

Gawande begins by describing all of the horrible realities of the ten percent rate of death for infants and children in Costa Rica in the fifties and sixties from infectious diseases and poor nutrition before radical changes were adopted in the seventies. He then moves on with one of his key observations about why Costa Rica has a significantly longer life expectancy than we do for a much smaller percentage of their GDP and actual money spent/person:

So when did Costa Rica’s results diverge from others’? That started in the early nineteen-seventies: the country adopted a national health plan, which broadened the health-care coverage provided by its social-security system, and a rural health program, which brought the kind of medical services that the cities had to the rest of the country…In 1973, the social-security administration was charged with upgrading the hospital system… In this early period, the country spent more of its G.D.P. on the health of its people than did other countries of similar income levels—and, indeed, more than some richer ones. But what set Costa Rica apart wasn’t simply the amount it spent on health care. It was how the money was spent: targeting the most readily preventable kinds of death and disability…

That may sound like common sense. But medical systems seldom focus on any overarching outcome for the communities they serve. We doctors are reactive. We wait to see who arrives at our office and try to help out with their “chief complaint.” …We move on to the next person’s chief complaint: What seems to be the problem? We don’t ask what our town’s most important health needs are, let alone make a concerted effort to tackle them. If we were oriented toward public health, we would have been in touch with all our patients, if not everyone in the communities we serve, to schedule appointments for vaccination against the coronavirus, the No. 3 killer in the past year…We would have made a priority of preventing disease, rather than just treating it. But we haven’t.

I added the bolding in the paragraph above because he is describing key factors in our dysfunctional and wasteful system of care. We practice reactionary medicine and we do not adequately consider or try to correct the environmental and social circumstances that are the origin of much of the disease that plagues our patients.

Today in America, we have a huge problem with maternal and infant death, especially in minority populations. Maternal and infant mortality were the biggest problems that faced Costa Rica in the seventies and improving maternal and infant survival was the first corrective action that they took. Now mothers and infants are better off in Costa Rica than in America. What are we doing about this disgrace? While Costa Rica was improving the experience of women and infants we have been enmeshed in a fifty-year effort to abolish the benefit of choice granted by Roe v. Wade. Why worry about the number of women and infants who could be saved when we can eliminate abortion? I wish the religious right could bring the same enthusiasm to preserving the health of those women who want to be mothers as they do to forcing women who as a matter of choice don’t want to be a mother. This week the Supreme Court and the Texas legislature have demonstrated once again that in this country a controlling minority cares more about limiting abortions than improving the health of mothers and infants. Many of the same voices that want to protect an unborn fetus continue to block the expansion of Medicaid which would improve the access of millions of mothers and infants to the prenatal and postnatal care they need.

I once heard Atul say in a speech at our organization that for centuries improvements in health were stymied by our ignorance of basic science, what we did not know. Now we have the science and technology to do what we could not do before but now we are limited by incompetence. Ignorance and incompetence are not the only limits to what can be accomplished. To Gawande’s analysis of failure from ignorance and incompetence, I would add insensitivity. It is hard to admit, but when it comes to the health of women and children in poverty there are those among us who seem not to be concerned or moved by the suffering that exists. Their own priorities trump the needs of those who become the victims of the statistics that Costa Rica has proven can be improved.

Costa Rica did more than improve the care experience and survival of mothers and young children. Gawande describes what else happened:

Public-health strategies might be able to address mortality in childhood and young adulthood, but many people believe that adding years from middle age onward is a wholly different endeavor. Countries at this stage tend to switch approaches, deëmphasizing public health and primary care and giving priority to hospitals and advanced specialties.

Costa Rica did not change course, however. It kept going even farther down the one it was on…

The plan had three principal elements. First, it would merge the public-health services of the Ministry of Health with the Caja’s [Caja means “the fund” in Spanish and is the “nickname” of the C.C.S.S. or Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social which is the social security system in which Costa Ricans and foreigners with residency status must enroll.] system of hospitals and clinics—two functions that governments, including ours, typically keep separate—and so allow public-health officials to set objectives for the health-care system as a whole. Second, the Caja would integrate a slew of disparate records, combining data about household conditions and needs with the medical-record system, and would use the information to guide national priorities, set targets, and track progress. Third, every Costa Rican would be assigned to a local primary-health-care team, called an ebais (“eh-by-ees”), for Equipo Básico de Atención Integral en Salud, which would include a physician, a nurse, and a trained community-health worker known as an atap (Asistente Técnico en Atención Primaria). Each team would cover about four or five thousand people. The ataps would visit every household in their assigned population at least once a year, in order to assess health needs and to close the highest-priority gaps…

Again, in contrast to our stark political divisions over healthcare policy, the recommended system had universal bipartisan support and was set as one of Cota Rica’s highest priorities. It has survived several transitions of power between the right and left of center parties. Gawande’s guide was one of the chief players in the creation and passage of the system of blended public health and primary care. I have bolded what would seem like common sense to me.

…the plan was submitted to the legislative assembly [while a right of center government was in power], where it passed unanimously. A new government was elected, under the center-left President José María Figueres, but the plan had its full support. In fact, Figueres appointed Salas to be the head of the C.C.S.S.

Getting the bill passed without opposition would seem no small feat: Salas had made his pitch to a center-right government, then retained the backing of a center-left one. But, if such unanimity is hard to imagine in the United States, President Figueres told me that it wasn’t surprising in Costa Rica. “This is something which, in our culture, is politically easy to sell,” he said. It would put a doctor, a nurse, and a community-health worker in every neighborhood. Who could object to that?

My guess is that in America Senate Republicans would object. “Red State” legislatures would object. In Costa Rica, it seems everybody, no matter their political orientation, sees the benefit in improving the health of every individual in the community while improving the health of the community. With that support, the plan has been fully implemented and in place even longer than Costa Rica’s universal access to hospital care. Implementation it seems, also took substantial pressure off hospital and specialty services which were swamped with patients who had diseases and conditions that had gone unaddressed. The fact that everyone is enrolled in an “ebais” and has a PCP and a nurse and all their demographic and medical information accessible through a reliable information system prepared Costa Rica for the challenge of COVID. The system is so reliable that one of its users could not comprehend Gawande’s search for information about how it might fail from time to time.

I saw this reliability throughout our visits. Because everyone was enrolled with an ebais, everyone was contacted individually about a covid vaccination appointment—most at their neighborhood clinic and a few at home. One woman I met explained that she’d learned about her appointment by phone. I asked her what would happen if the ebais folks didn’t call. She looked at me puzzled. Maybe something was lost in translation. She repeated that she knew what week they would call, and they called. I persisted: What if they didn’t? She’d wait a couple of days and call herself, she said. It was no big deal. She asked me how things worked where I was from. I could only sigh.

Costa Rica employs all the clinical tools that I have thought were innovations here. There are group sessions ( shared medical appointments) for education and better management of chronic diseases like diabetes. During the pandemic, care was delivered by telehealth approaches like Zoom. Remote regions get equal access to care unlike what we see in our country. The results are spectacular:

The results are enviable. Since the development of the ebais system, deaths from communicable diseases have fallen by ninety-four per cent, and decisive progress has been made against non-communicable diseases as well. It’s not just that Costa Rica has surpassed America’s life expectancy while spending less on health care as a percentage of income; it actually spends less than the world average. The biggest gain these days is in the middle years of life. For people between fifteen and sixty years of age, the mortality rate in Costa Rica is 8.7 per cent, versus 11.2 per cent in the U.S.—a thirty-per-cent difference. But older people do better, too: in Costa Rica, the average sixty-year-old survives another 24.2 years, compared with 23.6 years in the U.S.

Gawande uses the facts to redirect attention to our inequities:

The concern with the U.S. health system has never been about what it is capable of achieving at its best. It is about the large disparities we tolerate. Higher income, in particular, is associated with much longer life. In a 2016 study, the Harvard economist Raj Chetty and his research team found that the difference in life expectancy between forty-year-olds in the top one per cent of American income distribution and in the bottom one per cent is fifteen years for men and ten years for women.

But the team also found that where people live in America can make a big difference in how their income affects their longevity. Forty-year-olds who are in the lowest quarter of income distribution—making up to about thirty-five thousand dollars a year—live four years longer in New York City than in Las Vegas, Indianapolis, or Oklahoma City. For the top one per cent, place matters far less.

We tolerate inequity by race, income, and location in ways that just are not seen in much poorer Costa Rica. We pass off the depth of the tragedy of our inequities with our glib comment that your life expectancy is more a function of your ZIP code than your genetic code, and then we shrug our shoulders and move on without making any effective changes. I guess there is some sense of equity in the reality that a “red state” Trump supporter in Idaho or Iowa is just as abused by the system as a Latinx woman in East LA. Gawande sees a silver lining in Chetty’s research:

In a way, it’s a hopeful finding: if being working class shortens your life less in some places than in others, then evidently it’s possible to spread around some of the advantages that come with higher income. Chetty’s work didn’t say how, but it contained some clues. The geographic differences in mortality for people at lower socioeconomic levels were primarily due to increased disease rather than to increased injury. So healthier behaviors—reflected in local rates of obesity, smoking, and exercise—made a big difference for low earners, as did the quality of local hospital care. Chetty also found that low-income individuals tended to live longest, and have healthier behaviors, in cities with highly educated populations and high incomes. The local level of inequality, or the rates at which people were unemployed or uninsured, didn’t appear to matter much. What did seem to help was a higher level of local government expenditures.

Gawande is seriously suggesting that we adopt much of Costa Rica’s methodology. He sees big opportunities in the public health approach to the treatment of problems like chronic hepatitis B and C.

What would this model look like in the United States? Consider the example of one common illness, viral hepatitis. Infection with either the hepatitis-B or the hepatitis-C virus can lead to severe liver damage and to chronic liver disease—a top-five cause of death for Americans between the ages of forty-five and sixty-four. It can also lead to liver cancer. More than four million people in the U.S. have a chronic hepatitis-B or hepatitis-C infection. Hepatitis C alone is the most common reason that American patients require liver transplants. We spend billions of dollars a year on treatment for these two viruses.

Ironically, it’s not what we can’t afford, it is what we can’t imagine or accept about our own inadequacies that limit our success and adds billions of wasted dollars to the cost of our flawed system of care.

But here again our system is designed for the great breakthrough, not the great follow-through. In Costa Rica, nearly ninety per cent of babies are vaccinated against hepatitis B at birth. (Mother-to-child transmission during childbirth is a significant pathway for infection.) In the U.S., only two-thirds are. Just twenty-five per cent of American adults are vaccinated against the virus. Our chronic-liver-disease rates have barely budged. In the meantime, new hepatitis-C infections have increased by almost thirty per cent since 2017…We know what needs to be done; we just don’t have the mechanisms to do it…systems aren’t equipped to do the same for the people in the communities they serve. Costa Rica shows how they could be.

I frequently imagine that people turn away or yawn when I mention doing away with healthcare disparities or pursuing the Triple Aim. We are impaired by our national disease of self-interest that precludes consideration of doing anything that might represent a change from what is failing us in ways that we will not acknowledge. We seem to fear that if we extend better care to everyone we will pay more or get less ourselves when in fact we already pay much more and get much less than we can seem to admit to ourselves.

As a “Quixote” I cared a lot but got very little accomplished. It feels like the experience of the last twenty years in healthcare has been a lot like our experience in Afghanistan. Many good people have tried to make a difference, much money has flowed, and things still aren’t much better or more secure. We need a generation of more effective Quixotes. We don’t need more technology. We don’t need to spend more money. We do need some new ideas that lead to the more effective organization and distribution of care. The problem reminds me of my favorite quote from Dr. Robert Ebert:

“The existing deficiencies in health care cannot be corrected simply by supplying more personnel, more facilities and more money. These problems can only be solved by organizing the personnel, facilities and financing into a conceptual framework and operating system that will provide optimally for the health needs of the population.”

Costa Rica seems to be the national embodiment of Dr. Ebert’s analysis. As I reflect back on my early years at Harvard Community Health Plan I realize that before the organization contracted the social diseases of the wider medical community, it espoused and piloted much of the philosophy and practice that Gawande reports from Costa Rica. It is a shame that the momentum was lost. It is sad for me to say, but I wonder when or if American healthcare will ever do the right thing.

Labor Day Is Here

.

I have a confession. I ride an e-bike. I am making progress toward walking for exercise since my very destructive fall late last February. I now have a hitech brace for my foot drop which is secondary to the peroneal palsy that I have had since the pain from my injured sciatic nerve subsided sometime in April. With my brace to limit my “foot drop” which was created by Boston Orthopedics and Prosthetics, I can walk four miles again at a pace of a little less than twenty minutes per mile, but as you may know, braces often are uncomfortable.

I am looking forward to my next appointment with the hope that the brace can be adjusted. I hope a little adjustment will make doing four miles less uncomfortable. My greatest hope is that someday the nerve will “wake up” and I will be back to normal. The literature suggests that the odds for recovery in time are good. When I realized that I was not able to walk for exercise I became very attached to my e-bike. I had fortuitously purchased my e-bike last year for our RV trip so that I could keep up with my wife when she was on her e-bike. When I was on my conventional bike she would leave me far behind,

Ironically, she is not riding much anymore so the bikes were just sitting in the garage until I began to try to exercise again after my fall. We live in a very hilly place. Many serious bicyclists can be seen training on our back roads in their bright outfits that make them look like they took a wrong turn off the Tour de France and ended up in New Hampshire.

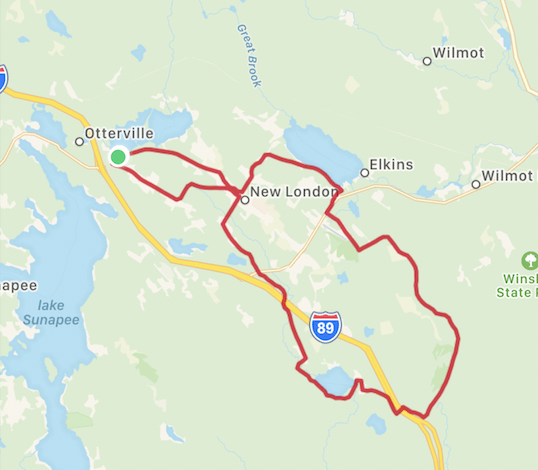

No one would ever mistake me for a refugee from the Tour de France, but I have been taking longer and longer rides using less and less “assistance” from the electrical heart of my bike. This last Tuesday on a perfect summer day I joined some of my friends who also have e-bikes on a two-hour twenty-three-mile jaunt over some gorgeous country roads. The centerpiece of our ride was looping around Kezar Lake which is a local jewel that has Mount Kearsage as a backdrop as you can see from the picture in today’s header. On the map below which I lifted from the app “Map My Ride,” I live at the green dot on Little Lake Sunapee. Kezar Lake is unnamed on the map but lies just below the logo for I 89. Mount Kearsarge, seen across the lake in the picture, lies between Wilmot and the logo for Winslow State Park which is on the mountain.

I have walked the three miles around Kezar Lake many times. Half of the road around the lake is not paved. In most places, the road lies between the homes and camps and the associated waterfronts that go with those homes and camps. As I was riding along with my friends and enjoying the views of Kearsarge I was struck by the beauty of the scene and took the picture. I have no clue whose dock, swim float, and sailboat I have captured in the picture, but the scene shouted “summertime!” to me. It makes me a little sad to know that summer is almost over. I can’t will the summer to last longer. I am sure that we will have a few scattered summer-like days as the fall rolls forward, but I am always astonished by the sense that the feel of summer ends at about six PM on the evening of Labor Day. That reality puts a lot of pressure on us all for this weekend.

Maybe summer is already over since on Monday evening I built a fire in the fireplace because we were having a chilly evening with rain. I don’t know how you plan to manage the transition this weekend from summer to fall, but I hope the weekend will be like summer for you. The long-range weather forecast for New London suggests that maybe summer is over and I won’t admit it. The high Saturday will be 70 and the sky will be partly cloudy. Sunday we are going to be in the sixties with some rain. The outlook for Monday is a little better, but the long-range forecast is downhill from Monday. It is at times like this that I remind myself of the cycle of the seasons. Summer will surely come again although global warming will guarantee that what we took for granted in the past may not be what we can expect for the future. Is there anything we can do together to make summer and all the seasons great again?

Be well,

Gene