May 22, 2020

Dear Interested Readers:

Chaos Borne Of History, Culture, Choice and COVID-19

When I was in that phase of childhood that Erickson referred to as “Industry vs. Inferiority,” somewhere between 6 and 11, I became a student and was hooked on “information.” My focus was on my World Book Encyclopedia and my map collection. I must have been pretty obnoxious because with the help of World Book I tried to become an authority on everything.

Most summers my family took a long car trip. Most of the time we would just drive from Oklahoma or Texas to the Carolinas to visit my grandparents, but over the years we also took trips to Chicago, Detroit, Canada (all the way to Quebec), New England, New York, Philadelphia, Washington, Colorado, and across the Southwest to the Grand Canyon and on to California. We visited many of the national parks and quite a few of the Civil War battlegrounds. I soon learned that I could get maps of each state and the various regions of America for free at the gas stations we visited along our journeys. Back home, I would pin the maps to the walls of my bedroom. In time the maps were like the wallpaper of my room. As people learned of my map collection, I was gifted maps from all over the world. I spent hours and hours studying the maps and looking up the places I saw on the maps in my World Book.

This bit of personal history is background for the revelation that with the COVID pandemic, I have rediscovered my fascination with maps and the questions that they can generate. It has become a routine for me to begin my day with a cup of coffee while I study the maps from the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center and other sources. I must admit that the maps are yielding less specific messages now than they were a few weeks ago. Back then I could ask why there were less than 20,000 cases in Russia when there were over 100,000 in Italy. To my surprise now, there are over 300,000 cases in Russia and only about 230,000 in Italy. As I followed the daily numbers it was hard for me to understand why the maps and associated data showed less than 10,000 cases in India with a population of over a billion when there were many times more cases in Iran. Now weeks later there are more than 100,000 cases in India, but it still lags Iran. The most recent map suggests that Canada has almost as many cases as China where the problem began. That assumes that we can believe the data from China where there have been virtually no no cases counted in the last six week.

There are equally confusing observations when we look at the maps for the United States. We all know that the New York area is our major hot spot. That New York is our hot spot is easy to understand. New York is very diverse. People come in and out from all around the world. It is very crowded. Before the lockdown the subways and the sidewalks were congested. Elevators were packed for rides of dozens of floors. A runny nose and a cough did not keep many people from going to work. But, how is that so different from the Washington/Baltimore area, Chicago, or Houston and why did Eastern Massachusetts end up with more cases than Southern California?

I find the Covid Tracking Project of the Atlantic to be a wealth of maps and useful information. On that site you can scroll through the states and come up with many many questions that have no answers. Why here and not there? When here, and how come so late there? When I was a child my World Book and my maps were a guide to understanding and mastery. With the COVID-19 pandemic we have learned many bits and pieces of information, but despite our maps and growing databases what stands out is that we persist with an amazing amount of uncertainty and ambiguity. Some would say that the more we have learned the less certain we have become about what might happen. If there is anything that makes us anxious it is uncertainty and ambiguity about big things. What makes a moment like this so very difficult is that as individuals with personal freedom, we reserve the right to respond to our anxieties in our own individual ways.

If there is anything in our national DNA that is true on all sides of our many ways of viewing the world, it is the concept of individual responsibility and personal liberty. If the Chinese numbers coming out of their early experience with the COVID-19 are true, the statistics may suggest that there is some survival benefit to an authoritarian state. In an authoritarian state any personal liberty that might exist can be quickly suspended for the benefit of the greater good once the state wakes up to the threat. There is a direct line of control from Beijing to the most distant realm of the state. If the technology exists, personal movement can be closely tracked without any concern for privacy.

In the pandemic we also get directives from our government. What is different here and in other western democracies is that there are many many points along the way where the individual can choose to follow or to disregard the suggestions that come down the line to us. We can see on the nightly news that our president flaunts the recommendations of his own staff of experts. He is a role model for those who see virtue in resisting the findings of experts and value “gut feelings” over science, and attention to one’s personal preferences over the good of the community. Not wearing a mask has become a personal political statement. In some quarters wearing a mask may suggest that you have socialist tendencies.

We highly prize our personal freedom, and embrace the variations in outcomes that individual preferences produce. What is less obvious to the most wealthy Americans is that the choices they make, when passed through the reality of increasing economic inequality experienced by many, greatly reduces the choices available to a growing number of our citizens who live by providing essential services. The uncertainty of the sum of all the personal choices, variations in opportunity, and entrenched inequities that have become the defining realities of our society leads to a confusing picture, and a difficult to predict outcome. When we are challenged by an event that requires a coordinated response it becomes impossible to be certain what we will do and how all of our independent actions will blend. The uncertain that arises from our individual freedom in how we act creates a growing sense of anxiety in all of us that arises from the chaos we helped to create. Even our response to the chaos becomes a further source of variation as some of us respond by saying, “Party on!” while others retreat in anger and fear.

Even with clear cut expectations coming from experts and authorities, we can’t predict very accurately the outcome of our collective responses. The possibility of chaos that goes far beyond uncertainty and ambiguity is real when all the possible options of our individual agency are coupled with a problem we don’t fully understand. It is daunting to realize that we have no way to predict with any certainty what path the pandemic will follow from past experience with this virus.

Our ancestors could not predict the weather with our level of accuracy because they did not have the environmental understanding, the algorithms, the satellites, or the computers we have. I get notices on my cell phone that say a brief shower will begin at 7:34 PM. My great grandfather, the country doctor, got no such notices, and if there were weathermen in his day, they did not have satellites or computers, and he had no cell phone, radio, or television with which to access their predictions, but he did have enough personal experience with the weather to know when to carry an umbrella. He did not fully understand where the weather came from or what caused it to rain or snow, but he had experience with it that enabled him to deal with it. He was equipped to make good choices– umbrella vs. rain coat vs. take a chance.

With the COVID pandemic we have scant experiences that have varied widely from country to country for reasons we do not really understand. The thing that we know with the most certainty is that we have suffered almost a hundred thousand deaths and a huge financial injury that will probably take many years to overcome. We think we know how pandemics work, but the truth is that if you have seen one pandemic, you have seen one pandemic. We have some proof that extreme social distancing might reduce the level of uncertainty in our future. In retrospect, one analysis suggests had we begun the social distancing one week earlier we could have saved over 35,000 lives. Had we begun it at the end of February while our President was telling a huge crowd at a re election rally in South Carolina that the virus was the latest Democratic hoax, we would have saved more than 80,000 lives.

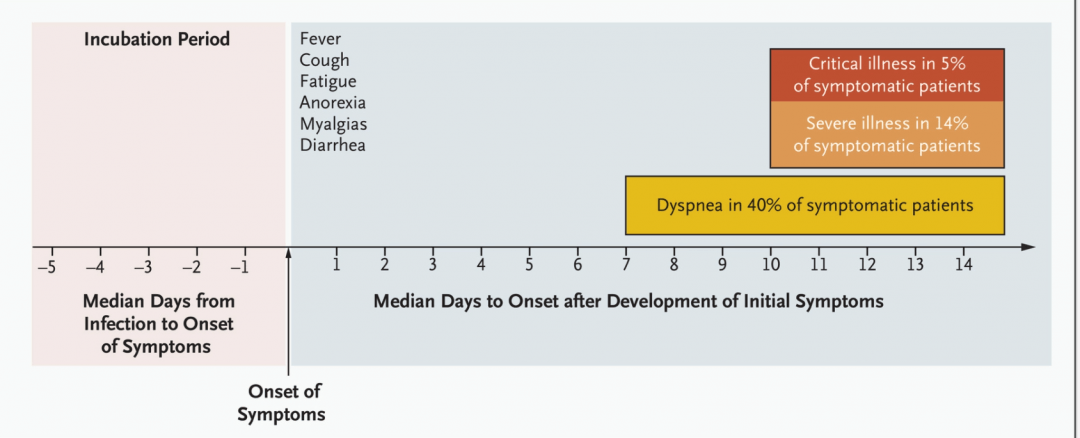

There is much that we do not know about what the virus will do, but we are learning how to manage patients who are very ill with the virus. The New England Journal has published an excellent PDF this week describing how to treat those who are most ill. In the article there is an excellent graphic that shows the problem that we face going forward.

The graphic nicely shows the prolonged incubation phase when the carrier is asymptomatic. Then comes the period of several days when the symptoms are mild and perhaps confusing, but spread is possible. Perhaps, that is when a test will be ordered. If we postulate someone getting exposed to the virus on the beach this weekend in Florida, they will be spreading the virus for five to ten days before their test is done and we begin to look for their contacts. The more unlucky carriers of the virus will begin to need care at a hospital by June 7, and might require intubation a few days later. With luck they may be extubated by the end of the month. They might also die by Father’s Day. I point out the delays only to underline that the foolish things and unfortunate things that happen today will play out over a month. By the time there is evidence that will convince mayors or governors to act to reinstate the more severe forms of social distancing, we may be well on our way to the second curve that we will need to flatten.

The desire that many Americans are expressing to return to normal and to make their own decision about how to respond to the virus is not much different than what we see in medical practice where “clinical autonomy” is a highly prized and is a virtual sacred professional prerogative. Coordinated activity may look great in a chorus line or a marching band, but we prefer freedom and independence from the direction of others. Somewhere along the line of time many Americans have developed a deep dislike of “experts” and an admiration of the macho man who shoots from the hip and feels the right thing to do in his “gut.” This fearless spontaneous hero is a mythical “risk taker” who bows to no one.

Two months ago the pandemic was our only challenge. We had some confidence that social distancing and sheltering at home would blunt the pace of the spread of the virus. Now we have a more complex situation in that we have a huge economic threat as an overlay to a map that shows a variable impact from the virus. Earlier this week I read “How chaos theory helps explain the weirdness of the Covid-19 pandemic. No one can predict the future of the pandemic. That doesn’t mean we’re powerless.” The article, written by Brian Resnick, appeared in Vox. Resnick quotes Stephen Kissler, an infectious disease modeler:

“Little shifts can have really disproportionately sized impacts” in a pandemic. And scientists have a name for systems that operate like this: chaos.”

Resnick uses the movement of a double pendulum to expand our concepts of chaos. We have known since the work of Sir Issac Newton how to predict the movement of a pendulum, but even now we are challenged when we try to predict the movement of a double pendulum. I’ll let him explain his point:

There’s a simple mechanical that is helping me understand the many possible futures we face with the Covid-19 pandemic.

It’s the double pendulum, and as a physical object, it’s very simple: A pendulum (a string and a weight) is attached to the bottom of another. Its movement is explained by the laws of motion written by Isaac Newton hundreds of years ago.

But slight changes in the initial condition of the pendulum — say it starts its swing from a little higher up, or if the weight of the pendulum balls is a little heavier, or one of the pendulum arms is a bit longer than the other — lead to wildly different outcomes that are very hard to predict.

The double pendulum is chaotic because the motion of the first pendulum influences the motion of the second, which then influences the entire apparatus. There isn’t a simple scale or ratio to describe how the inputs relate to the outputs. A one-gram change to the weight of a pendulum ball can result in a very different swing pattern than a two-gram change.

It teaches us to understand the mechanics of a system — the science of how it works — without being able to precisely predict its future. It helps us visualize how something that seems like it should be linear and predictable just isn’t.

The double pendulum shows us that simple systems aren’t simple at all. Complicated ones, then? God knows.

Resnick reminds us that the pandemic is even less predictable than the movement of a double pendulum. If the threat of a virus with unknown power and capabilities was hard to understand when we first became aware of it, things are worse now because of our variations in our responses to it. There are also many factors that might aid prediction that remain as unknown. Our actions continue to multiply our uncertainty as we add introduce huge variation in activity from state to state. In each state there is a spectrum of attitudes within the population that is unique to its economic, cultural, and ethnic diversity. The outcome of policy in a red state where the legislature or the courts undermine the governor’s intent and leadership will vary greatly from a state with a well developed social safety net. A perfect example of variation is the difference in unemployment benefits across the spectrum of states. It is much better to be unemployed in Massachusetts than it is in Florida. He quotes Eleanor Murray, an epidemiologist from Boston University who sums up the situation in just a few words:

“I think we have more uncertainty now than almost any other time,”…“Now at this moment, some places are thinking about continuing lockdown. Some places are thinking about opening. Opening means different things in different places. There’s such a range of possible actions that different areas are taking, that it’s really hard to predict.” Our actions influence the results, which then, in turn, influence our actions.”

It is easy to become more depressed when reading Resnick’s article and thinking about the increase in chaos and uncertainty that is being introduced by attempts to return to more normal patterns of activity. He points out that there is benefit in understanding how chaos is compounded. I have said many times before that there is little that I personally control other than my own choices. Any of us can choose to follow the best advice of our scientists. We don’t need an authoritarian government to force us to do what the best science suggests that we should do to protect ourselves and reduce the likelihood of spread. Resnick gives us the “We have choices” message:

Thinking about the future of the pandemic means wrestling with uncertainty, both personally and as a wider community. It also means dealing with what’s not likely to happen: The virus disappears in the next several months. If it does, it will do so for reasons scientists do not understand or can currently explain.

There’s a lot in this chaotic pandemic system we can’t control. Let’s be serious about the ones we can.

Ed Jong, a writer at the Atlantic, has already written several excellent articles about the COVID-19 pandemic and how it will evolve. I think his efforts are at the top of the journalistic attempts to provide reliable insight to what lies ahead. This week he published an article that captures the essence of our dilemma. It’s aptly entitled “America’s Patchwork Pandemic Is Fraying Even Further: The coronavirus is coursing through different parts of the U.S. in different ways, making the crisis harder to predict, control, or understand.”

This week we have learned that the Chinese are not the only government that manipulates statistics to make things look better than they are. They also try those tricks in several of our states, especially in Georgia and Florida. Jong begins the article with a succinct snap shot showing where we really are versus where some states and the president might wish to say we are:

There was supposed to be a peak. But the stark turning point, when the number of daily COVID-19 cases in the U.S. finally crested and began descending sharply, never happened. Instead, America spent much of April on a disquieting plateau, with every day bringing about 30,000 new cases and about 2,000 new deaths. The graphs were more mesa than Matterhorn—flat-topped, not sharp-peaked. Only this month has the slope started gently heading downward.

This pattern exists because different states have experienced the coronavirus pandemic in very different ways. In the most severely pummeled places, like New York and New Jersey, COVID-19 is waning. In Texas and North Carolina, it is still taking off. In Oregon and South Carolina, it is holding steady. These trends average into a national plateau, but each state’s pattern is distinct. Currently, Hawaii’s looks like a child’s drawing of a mountain. Minnesota’s looks like the tip of a hockey stick. Maine’s looks like a (two-humped) camel. The U.S. is dealing with a patchwork pandemic.

The patchwork is not static. Next month’s hot spots will not be the same as last month’s. The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus is already moving from the big coastal cities where it first made its mark into rural heartland areas that had previously gone unscathed. People who only heard about the disease secondhand through the news will start hearing about it firsthand from their family. “Nothing makes me think the suburbs will be spared—it’ll just get there more slowly,” says Ashish Jha, a public-health expert at Harvard.

We are back to maps and the way this virus causes them to change from day to day. I like Jong’s metaphor of a “patchwork.” We are like a big quilt where every state, indeed every individual, gets to determine the color and shape of their response to uncertainty. Each of us designs our own tiny piece of a much larger blanket.

As I have enjoyed reading Jong’s articles I have come to realize that he likes to make three big points. Here are his three points that explain our chaotic patchwork experience:

I. The Patchwork Experience

In this section Jong describes the variable experiences from the virus that we have had until now.

A patchwork pandemic is psychologically perilous. The measures that most successfully contain the virus—testing people, tracing any contacts they might have infected, isolating them from others—all depend on “how engaged and invested the population is,” says Justin Lessler, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins. “If you have all the resources in the world and an antagonistic relationship with the people, you’ll fail.” Testing matters only if people agree to get tested. Tracing succeeds only if people pick up the phone. And if those fail, the measure of last resort—social distancing—works only if people agree to sacrifice some personal freedom for the good of others. Such collective actions are aided by collective experiences. What happens when that experience unravels?

“We had a strong sense of shared purpose when everything first hit,” says Danielle Allen, a political scientist at Harvard. But that communal mindset may dissipate as the virus strikes one community and spares another, and as some people hit the beaches while others are stuck at home. Patchworks of risk and response “will make it really hard for the public to get a crisp understanding of what’s happening,” Rivers says.

He suggests that one outcome will be a splintering of the nation. I think we already see evidence of that as people demonstrate for a return to normal even if it means many might die.

Confused people will retreat to the comfort of preexisting ideologies. The White House’s baseless attempts to claim victory will further divide the already fragmented states of America. “In the face of medical uncertainty, people make decisions by returning to their own groups, which are very polarized,” says Elaine Hernandez, a sociologist at Indiana University Bloomington. “They’ll want to avoid being stigmatized, so they’ll follow what people in their networks are doing [even if] they don’t really want to go out.”

There is also a second possible outcome. The pandemic may draw the majority of us closer together:

Economic indicators support this view. Even in conservative states, activity plummeted before leaders closed businesses, and hasn’t rebounded since restrictions were lifted.

What our experience in this new phase of an attempt to return to normal will be remains unclear.

II. The Patchwork Response:

Jong describes what he means:

A patchwork was inevitable, especially when a pandemic unfolds over a nation as large as the U.S. But the White House has intensified it by devolving responsibility to the states. There is some sense to that. American public health works at a local level, delivered by more than 3,000 departments that serve specific cities, counties, tribes, and states. This decentralized system is a strength: An epidemiologist in rural Minnesota knows the needs and vulnerabilities of her community better than a federal official in Washington, D.C.

But in a pandemic, the actions of 50 uncoordinated states will be less than the sum of their parts. Only the federal government has pockets deep enough to fund the extraordinary public-health effort now needed. Only it can coordinate the production of medical supplies to avoid local supply-chain choke points, and then ensure that said supplies are distributed according to need, rather than influence. Instead, Trump has repeatedly told governors to procure their own tests and medical supplies….the Trump administration has ceded the U.S. to the virus.

The U.S. now heads into summer only slightly more prepared to handle the pandemic that cost it so dearly in the spring…“It’s inevitable that we’ll see stark increases in infections in the next weeks,” says Oscar Alleyne of the National Association of County and City Health Officials.

Jong acknowledges that we are testing many more people now and that several states have vastly improved their abilities to trace contacts, but we are far from certain that these efforts will be sufficient:

Will this system, combined with mask wearing and hand-washing, be enough to contain a patchwork pandemic? Complicating matters, people with COVID-19 can spread the coronavirus before showing symptoms.

III. The Patchwork Legacy:

In this section of the article Jong reminds us that where we are now is in many ways an extension of where we came from. We did not live in a equitable utopian society before the virus visited us. He writes:

The current patchwork is not random. Nor is it solely the consequence of America’s actions in 2020. It has emerged from a much older, deeper patchwork.

U.S. policies that evicted Native Americans from their own lands have long left indigenous peoples with insufficient shelter, water, and resources, making them vulnerable to infectious diseases like smallpox, cholera, malaria, dysentery, and now COVID-19…Thanks to traumas that accrued over generations and stressors that accrue over individual lives, the Navajo Nation has more per capita cases of COVID-19 than any U.S. state and nine times as many per capita deaths as neighboring Arizona. While Arizona has loosened its distancing restrictions, the Navajo Nation has been forced to tighten its orders.

Black Americans have fared little better. After the Civil War, white leaders deliberately kept health care away from black communities. For decades, former slave states wielded political influence to exclude black workers from the social safety net, or to ensure that the new wave of southern hospitals would avoid black communities, reject black doctors, and segregate black patients. “Federal health-care policy was designed, both implicitly and explicitly, to exclude black Americans,” wrote the journalist Jeneen Interlandi for The New York Times’ 1619 Project.

This is one reason why the U.S. still relies on employer-based insurance, which black people have always struggled to access. Such a system “was the only fit for a modernizing society that could not abide black citizens sharing in societal benefits,” wrote my colleague Vann Newkirk II. Over the past century, every move toward universal health care, and thus toward narrower racial inequities, was fiercely opposed. The Affordable Care Act, which almost halved the proportion of uninsured black Americans below the age of 65, was most strongly fought by several states with large proportions of black citizens.

If you read any of the article, please read this section. Trust me there is a lot more that I would put under the title of “we reap what we sow.” What emerges from the analysis is that by denying adequate care to so many people we have threatened the health of everyone. In a pandemic we can be reminded that when the bell tolls we should, “Ask not for whom the bell tolls. It tolls for thee.” And, for me as well as for Donald Trump. The virus reminds us that like it or not, deny it at your peril, we are all connected. It’s the best argument one can make for universal free healthcare.

These inequities will likely widen. Even before the pandemic, inequalities in poverty and access to health care “were concentrated in southern parts of the country, and in states that are politically red,” says Tiffany Joseph, a sociologist at Northeastern University. Not coincidentally, she says, those same states have tended to take social-distancing measures less seriously and reopen earlier. The price of those decisions will be disproportionately paid by black people.

Vulnerability to COVID-19 isn’t just about frequently discussed biological factors like being old; it’s also about infrequently discussed social ones. If people don’t have health insurance, or can afford to live only in areas with poorly funded hospitals, they cannot fight off the virus as those with more advantages can. If people work in poor-paying jobs that can’t be done remotely, have to commute by public transportation, or live in crowded homes, they cannot protect themselves from infection as those with more privilege can.

This point cannot be overstated: The pandemic patchwork exists because the U.S. is a patchwork to its core. New outbreaks will continue to flare and fester unless the country makes a serious effort to protect its most vulnerable citizens, recognizing that their risk is the result of societal failures, not personal ones.

Jong rightly reminds us that even if we quickly find a vaccine that ends this pandemic, we will be vulnerable to other new ones which follow COVID like COVID followed SARS and MERS. Ech new virus has the possibility of being a bigger problem than its predecessor. [By the way be hopeful, but be prepared to be disappointed by the recent vaccine hype.]

And while a vaccine will protect against only COVID-19 (if people agree to take it at all), social interventions will protect against the countless diseases that may emerge in the future, along with chronic illnesses, maternal mortality, and other causes of poor health. “This pandemic won’t be the last health crisis the U.S. faces,”… “If we want to be on better footing the next time, we want to reduce the things that put people at risk of being at risk.”

Of all the threats we know, the COVID-19 pandemic is most like a very rapid version of climate change—global in its scope, erratic in its unfolding, and unequal in its distribution. And like climate change, there is no easy fix. Our choices are to remake society or let it be remade, to smooth the patchworks old and new or let them fray even further.

I will leave it there, except to say that the chaos and uncertainty of the moment are in part related to this novel new virus, but in greater ways our position is derivative of who we are, how we behave, what we have done in the past, and how we react in the moment. We can’t change what has already happened, but we can individually and collectively try to extract learning from the experience and apply those insights to the road ahead. Medicine is uniquely positioned to lead the way. We understand science, and we know from experience that outcomes are best when we blend the personal with the collective with the objective of improving the health of the community and of every individual within the community. We have the tools to manage chaos and uncertainty.

A Different Memorial Day Kicks Off Summer

If you have a garden in New England, Memorial Day has an extra significance for you because it is common knowledge that you should try to get your garden in over the holiday weekend. Just Google “plant your garden, New England, Memorial Day” and you will see what I mean. One of the Boston television stations has done a little piece this week about Memorial Day and gardening. It has been a late spring. We have had a few nights in the last two weeks that were below freezing and the potted plants on the deck had to come in from the cold, but I have faith in the fact that by historical data the last freeze of the 2019-2020 winter is behind us although the weather.com tells me that there has been freezing weather in Concord, New Hampshire which is 35 miles South of New London as late as June 26. The usual range for my area is April 30 to May 20 which means the little garden rule has a five day margin this year. Memorial Day never comes before May 25th. This year we are having the earliest possible Memorial Day.

Kearsarge Neighborhood Partners, the non profit that many of my friends have established and where I am now devoting many hours a week of volunteer time is concerned about sustainable food sources. Our local hospital is writing “prescriptions” for fresh vegetables. KNP has now pulled together a coalition that includes the hospital to offer assistance to many families who want to grow their own vegetables. You can read all about it on our website. Just click on this link and look for FREE: “Garden in a Tray” for Growing a Family Garden. Helping people to grow their own vegetables fits nicely into our vision and mission.

I love watching other people, mostly my wife, garden. My role is usually to carry plants, haul mulch and sacks of soil, and move an occasional rock. I am motivated in my labors by the anticipation of the convenience of stepping out my door to easily harvest fresh tomatoes, kale, peppers, cucumbers, and maybe even a watermelon a few months from now.

It’s been a great week to be outdoors. I have discovered a new hike that is just about a mile and a quarter from my home. My first trip over to the trail was last Sunday with my son who is still keeping a wide berth from us because of a recent quick trip to Brooklyn. On Tuesday I introduced Tom Congoran to the Phillips Memorial Preserve Trail. Tom and I walk together at least once a week. He was the CFO of Atrius during my tenure and lives 25 miles south of me in Hopkinton, New Hampshire where there are also some great walks. If you want to get a sense of what we saw on our trek just click on the link. You can also look at the header for this post. I love the delicate flower of trillium, and I was delighted to see that many of the flowering forms of ground cover, including trillium, were coming out along the shady trail. It is a glorious time of year, and the notorious black flies have not been too bad.

Whether you are planting a garden or walking in the woods, I hope that you will continue to practice social distancing during this first weekend of our COVID summer. we are getting tired of or isolation, and the idea of a summer without big gatherings is a little weird, but it is also smart. Who knows if we have a vaccine by the fall (highly unlikely despite all the hype) maybe we will have a traditional Thanksgiving! Remember, no matter how frustrated and disappointed we may become, we can’t wish it all away. We must endure and find pleasure and company in what is available to us . We must be smart. So,…

Be well! Practice social distancing. Wash your hands frequently. Don’t touch your face. Cover your cough. Stay home unless you are an essential provider. Follow the advice of our experts. Assist your neighbor when there is a need you can meet. Demand leadership that is thoughtful, truthful, capable, and inclusive. Let me hear from you often, and don’t let anything keep you from doing the good that you can do every day,

Gene