May 19, 2023

Dear Interested Readers,

You Can’t Get There From Here

The statement “You can’t get there from here!” was made famous in a brief comedy monologue entitled “Which Way to Millinocket? that was created by the very talented comedy team of Marshall Dodge and Bob Ryan more than fifty years ago. I know that I have referenced the routine before, some years ago, but if you have never heard the routine, click on the link. It will be an enjoyable diversion of less than a minute and a half. Nothing spoils a joke or a comedy routine more effectively than trying to explain the punch line, but if you need help here is the explanation of the phrase, which surely predates its use by Dodge and Ryan:

Idiom: You can’t get there from here

Meaning:

US expression used in the New England area (most frequently in Maine) by persons being asked for directions to a far distant location that cannot be accessed without extensive, complicated directions.

I enjoy the wisdom of the phrase whenever I realize that I need to “cut my losses.” I have usually had an idea, perhaps even a “vision,” of something I want to accomplish or build. After many failed efforts to turn the idea or the vision into reality, it dawns on me that I am going at the project in a way that will never be successful and that I need to go in a new direction. At that transformational moment, metaphorically, I realize that my problem is that “I can’t get there from here,” and like it or not, I need to start all over with a new approach.

Sometimes tools that we depend upon fail us. Recently, I have been walking two great black labs that belong to an older woman who requested help through Kearsarge Neighborhood Partners. I did not know her, and I was not exactly sure how to get to her home so I plugged her address into Google and set out with full confidence that I the ap would lead me to her door. Not so. Google makes errors. The original route it plotted got me near her home but with several acres of forest between a dead-end road and her home. I had to turn around and actually read a map to find my destination because I could not get there from where Google had taken me. Google is great, usually, but not always, and sometimes it leaves you saying, “I can’t get there from here!”

I frequently mutter to myself, “We can’t get there from here” when I think about the current state of our healthcare system and goals like universal access, healthcare equity, or the Triple Aim. There is another phrase, “The harder I try [or the hurrier I go], the behinder I get,” that pops into my head in those moments when it feels like great efforts are leading to setbacks and continuing frustration. Crossing the Quality Chasm was published in 2001, and in those heady days, it felt like we had a road map of a super highway to the healthcare system of the future that would be the reward for decades of effort and lessons learned. Now over twenty years later, I often feel like after a lot of effort we have lost ground in the pursuit of our goal. We have been trying hard and getting “behinder.”

Last December, Sabrina Corlette and Christine H. Monahan published an article in the New England Journal of Medicine entitled “U.S. Health Insurance Coverage and Financing.” The title is very misleading. A more appropriate title should have been “If You Desire Universal Coverage and Healthcare Equity, You Can’t Get There Form Here.” The article is an overview of our attempts to reach those goals since 1912. Yes, I did write 1912. The article covers much of the same ground that was covered in the 2009 book by David Blumenthal and James Marone entitled The Heart of Power which traced the effort to improve access to American healthcare from Teddy Roosevelt to Barack Obama.

The authors pick up the story where we are now, at what we hope is the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. They begin by writing:

The Covid-19 pandemic has shone a spotlight on the fragmented nature of the U.S. health care system. Some Americans were fortunate to enter the pandemic period with comprehensive health insurance and to retain their coverage as the public health emergency dragged on for weeks, then months, then years. Some people have been protected, if temporarily, by federal congressional and administrative actions designed to expand subsidies for private insurance, maintain Medicaid enrollments, and reimburse health care providers for testing uninsured people for SARS-CoV-2 and treating those who are ill. But others continue to slip through the many cracks in our system and find themselves imperiled not only by a life-threatening virus but also by life-ruining medical bills.

What they imply is true when they write “Some people have been protected, if temporarily, by federal congressional and administrative actions…” For a little while we did a little better, but that temporarily improved state for some is in a state of rapid return to a worse “normal.” The debt limit controversy may even further undermine the access to care that many enjoyed through the short-term loosening of Medicaid enrollment rules that they enjoyed during the COVID emergency.

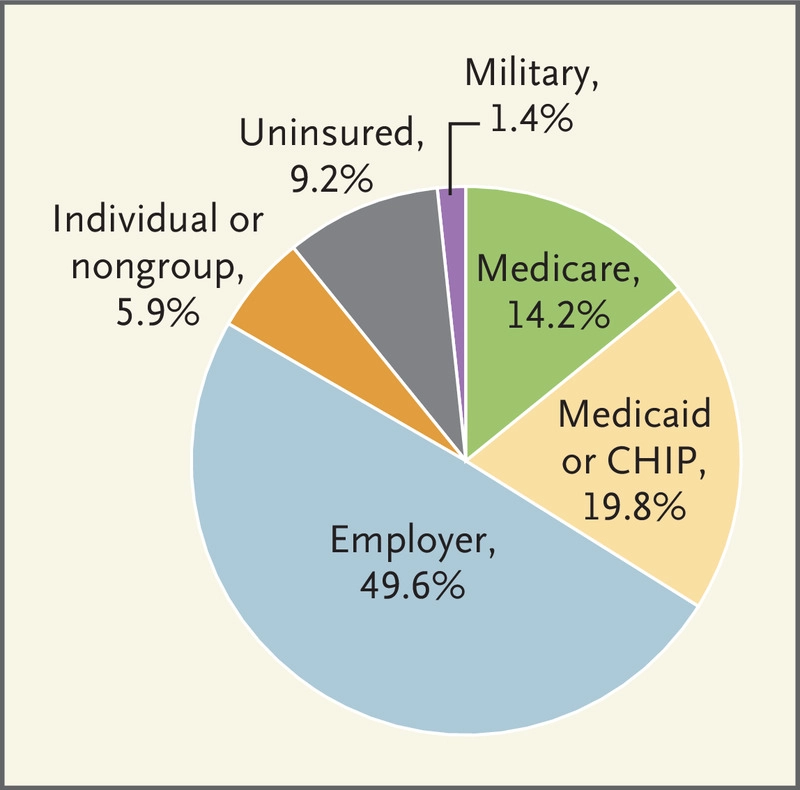

The authors provided a “pie chart” showing the state of coverage in 2019 prior to the pandemic. 9.2% of the population lacked coverage. That number doesn’t include many of the more than 10 million undocumented immigrants who are an important part of our workforce. Besides showing the shameful fact that over 9% of the population, over 30 million people, had no coverage, it also shows the patchwork nature of our system of care. What the pie chart doesn’t show is that the ACA did expand coverage and standardized what must be covered and did away with “prior conditions” as a barrier to coverage. The ACA did move us down the road, but it was not a road that led then or perhaps ever to universal coverage, healthcare equity, an improvement in outcomes, or a reduction in total healthcare costs.

U.S. Health Insurance Coverage, 2019.

The authors continue to describe who is still excluded from a system that is currently failing many who are covered:

If you work full time for a company that chooses to offer benefits, you might be eligible for employer-sponsored insurance. Depending on your income, state of residence, and other factors, you might qualify for Medicaid. You could also fall through the cracks: 12 years after the enactment of the ACA, more than 9% of Americans remain uninsured (see pie chart).

Many people in the United States work for employers that do not offer insurance or do not sufficiently subsidize it, making it unaffordable for lower-income workers. Most documented immigrants must wait 5 years to qualify for Medicare or Medicaid; those who are undocumented may never be eligible for any type of government insurance. And immigration status aside, millions of people live in states where eligibility rules mean they are actually too poor to qualify for subsidized coverage.

They then state the obvious:

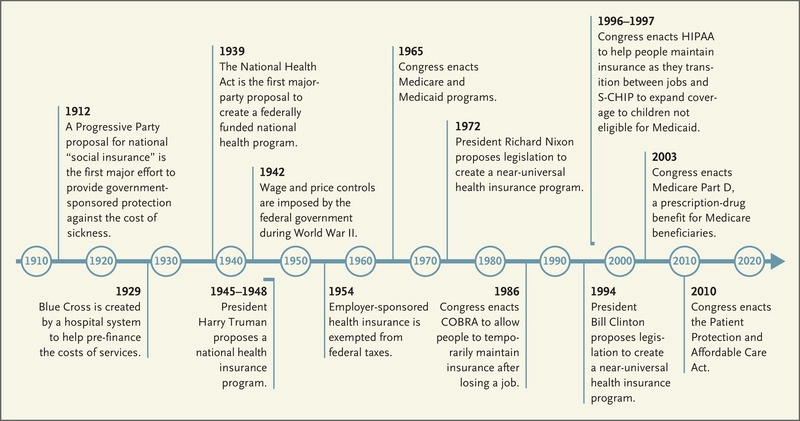

No one would purposefully design the system we have. Unlike many of our peer countries, the United States has never had a centrally planned, cohesive system to help its citizens obtain and pay for health care services. Ours is a system built on happenstance, unintended consequences, and gap filling (see timeline).

History of the U.S. Health Care System, 1912–2010.

They present us with a very interesting timeline that shows the evolution of our mess, and in their text, they add further insights that reveal how we got to this moment, but more important than a timeline of our failures is their explanation for why it has been so hard for us to do what so many other countries have accomplished:

…efforts all foundered in the face of opposition from health insurers, the American Medical Association, and other health industry stakeholders, as well as concerns about the proposals’ costs.

The dominant finance mechanism from the beginning until now has been fee-for-service. Harry Truman made an effort to create universal access with a government-run system of care:

A proposal by President Harry Truman would have created a federally run, compulsory national insurance program, and Presidents Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton both envisioned systems of universal insurance with responsibilities shared by the government and employers.

Blumenthal and Marone point out in their book that FDR almost included universal healthcare in the New Deal. It turns out that FDR’s son was married to the daughter of Harvey Cushing the famous Brigham neurosurgeon and a dominant force within the AMA. They were co-grandparents and close confidants. Cushing convinced Roosevelt not to include healthcare in the New Deal. FDR reportedly recognized the missed opportunity and planned to rectify it at the end of World War II, so the program that Turman tried to pass had its roots in the New Deal.

Obama was a student of all of the failures. We need to remember that he had sixty votes in the Senate, but one of those votes belonged to Joe Lieberman from Connecticut where there were powerful insurance companies. Leiberman was an independent who caucused with the Democrats and was never going to allow a program that abandoned the insurance industry. He blocked a “public option.” The ACA was an improvement, it even contained experiments within Medicare of ACOs that offered value-based contracts, but it is not and will not be the solution to our healthcare problems with costs and inequities because it is built on a chassis of employer-based fee-for-service funding. How we will migrate toward something that is better has become a question that feels like it is being lost in the conversations about inflation, debt limits, and other more immediate concerns like immigration, the war in Ukraine, gun violence, and efforts to curb global warming.

I fear that one of the reasons that healthcare coverage is not the issue that it was in 2008 or even in 2016 is that people are afraid to give up their Medicare or their employer-based insurance for something that they don’t fully understand and sounds like a “socialist program.”

The resolution of the debt ceiling crisis will require compromises. It seems clear that increases in taxes are a non-starter as a part of the deal. Veterans’ benefits, Medicare, social security, and military budgets are politically protected. Medicaid, SNAP benefits, education, budgets of government agencies in general, unspent COVID funds, and student loan forgiveness seem like available targets. There is Republican enthusiasm for work requirements for benefits like SNAP. Unfortunately, cutting most of these programs will fall heavily on the poor, and are likely to negatively impact the social determinants of health. Sadly, almost any resolution of the debt ceiling is likely to take us further from our desired destination of equitable healthcare for everyone in America. We probably won’t have a path to “get there” from where we will be after the debt ceiling discussion is over.

It would seem that even if everyone realized that “You can’t get there from here,” there is still no consensus on where “there” is and whether enough people want to get there if there is any risk of the trip personally costing them something. As I mentioned in these notes a few months ago, Matthew Desmond’s recent book, Poverty, By America argues that collectively we have the resources to end poverty and give everyone the healthcare, housing, education, and work opportunities they need. The Atlantic magazine published an interview this week that Annie Lowrey conducted with Desmond. The article is entitled “The War on Poverty Is Over. Rich People Won.” Lowrey’s first question opened the door for Desmond to demonstrate that we are on the wrong road that doesn’t go where we should want to go. I hope that you will read the whole interview. It is not long.

Annie Lowrey: How is poverty different in America than in its peer countries?

Matthew Desmond: We have more of it. We have double the child-poverty rate of Germany and South Korea. We have a lot less to go around with, in terms of fighting poverty. We collect a much smaller share of our GDP in taxes every year.

It’s different because it’s so unnecessary. We have so many resources. Our tolerance for poverty is very high, much higher than it is in other parts of the developed world. I don’t know if it’s a belief, a cliché, or a myth. You see a homeless person in Los Angeles; an American says, What did that person do? You see a homeless person in France; a French person says, What did the state do? How did the state fail them?

…We have massive amounts of evidence about the benefits of government spending on anti-poverty programs. But poverty is also about exploitation. We have all these anti-poverty programs that accommodate poverty without disrupting it. They’re not eliminating poverty at the root.

Like our poverty programs, our inadequate healthcare system is perpetuated because it is a quite beneficial business for many while it is a source of misery for others. Desmond has challenged us all by implying that poverty still exists in America because its presence benefits the majority. Is it possible that the same self-serving benefits for the majority are the reason that our deficient healthcare system is so difficult to reform? To get on the right road you must first realize that the road you are on will not get you to the destination where you say that you want to go. Once you see that you are on a road that will not get you to where you want to go, you must have the will to get on the right road. In their NEJM article Corlette and Monahan suggest that though many don’t see a need to get on a different road now, we are all vulnerable going forward.

Americans who have “good” insurance today may be surprised to learn that they, too, are vulnerable. Underinsurance is a growing problem, as fewer and fewer Americans are able to afford their share of costs. Premiums and deductibles continue to increase as health care costs rise, straining the budgets of families, employers, and state and federal governments. Unless and until policymakers curtail the power of health care monopolies to drive up costs and do more to limit health care prices across our array of public and private coverage systems, virtually everyone’s access to affordable care is at risk.

It is pretty simple. When you discover that “You can’t get there from here” the choice is to take another road or never get to where you need to go.

It’s Up and Down With The Temp– Plus Flies

We have had some great days over the last few weeks. I have enjoyed good walks in good weather on some lovely trails in the woods where I always see lots of rocks. This is the granite state. In many places, we have almost no topsoil. We live on a beautiful pile of rocks. When I try to move my bird feeders I have a hard time finding a place where I can push the stand down more than a few inches without hitting a rock. In the spring you can find where the processes of freezing and thawing of groundwater have pushed rocks up through the pavement of our local roads! Today’s header makes my point about how beautiful our rocks can be. 5

The sun was bright mid-week, but the temperature tanked into the forties during the day and we dropped into the low thirties overnight. The mercury fell to thirty at my house Wednesday night, and we built a fire to take the edge off the chill. At bedtime, I pulled out a blanket that I had prematurely stored thinking winter was over. To compound the misery from the undesired cold, I have a few itchy bites from the flies that invade us this time of year. All the uncertainty with the weather and bugs makes this the best time of year to leave New Hampshire.

We haven’t traveled much since the pandemic, but we are breaking out this coming week. Earlier this week, we got another COVID booster, and we are leaving town for the next two weeks. The next two Friday letters will be coming to you from France where we will be traveling with friends.

The trip has three parts, Part one is Normandy where we will see where my uncle served on D-day. Part two is a return visit to Paris which is always interesting. Notre Dame has burned and they say that the Seine is cleaner than it was the last time we were there in 1995. We will finish the trip by floating down the Rhone before flying home from Marseille. I hope that by the time we return, we will be well past our last freeze, and I can move some plants that spent the winter in my living room back onto the deck.

Whatever you will be doing over the next two weeks, let’s all hope together that the debt ceiling mess gets resolved without much increase in pain for those who struggle against the woes of poverty and are vulnerable to a healthcare system that often seems indifferent to their needs.

Be well,

Gene