March 26, 2021

Dear Interested Reader,

Have We Forgotten That The Cost of Care Is A Problem?

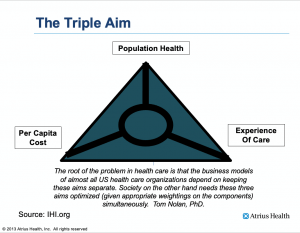

I mention the Triple Aim in many of my posts. In my opinion, the best graphic that presents the concept was created by the Institute For Healthcare Improvement (IHI) more than a dozen years ago. I used their graphic representation of the Triple Aim as a slide in almost every one of the scores of speeches and lectures I delivered between 2008 and 2014. I expect that most of you have seen it before.

Prior to the pandemic, we spent a lot of our energy trying to improve the experience and quality of care in response to pay-for-performance programs. There were legitimate attempts to lower the cost of care using value-based reimbursement programs like bundled payments and ACOs that showed promise but have not yet risen to the level of utilization to make much of a dent in the overall cost of care. My greatest concern about the future of healthcare when I was leading an organization and prior to the pandemic was the cost of care. As a healthcare executive and leader most of my thinking and actions were directed at the combination of improving the experience of care for the people who sought care from Atrius Health while continuously ratcheting down the cost of the care we provided by lowering our operational costs through efficiencies that could be gained from waste elimination utilizing Lean process management to lower our cost of operations.

My expectation had been that the day would come when yearly increases in payments would cease to be greater than the growth of the economy and the cost curve would flatten because of a refusal of the government and commercial payers to pay more. So far that has not happened. What has happened is that more and more of the insurance “risk” of the cost of care has been shifted to patients through a combination of mechanisms. Employers are paying less of the total insurance cost. As a result, more money is being deducted from paychecks to cover increases in premiums. The coverage that is purchased is less for a higher price. There are greater deductibles and the cost of what the patient must pay continues to rise. Until recently if you were hospitalized you could expect “surprise” medical bills from out-of-network pathologists, emergency physicians, anesthesiologists, and radiologists.

The pandemic has changed everything and distracted any attention that cost was getting. I sit on two boards and provide occasional advice to one federally qualified health center. Patient experience and costs remain concerns for all three organizations, but managing the systems through the distortions to practice, losses of revenue from elective surgeries, and staffing issues shift the concerns from cost to revenue. I expect that most healthcare organizations have stopped paying much attention to cost and are paying more attention to the third leg of population health. The shift in attention and focus created by the pandemic has been very informative because it has shown us that our lack of attention to the health of the community has challenged both the experience of care for individuals as well as the cost of care.

Prior to the publication of Crossing the Quality Chasm twenty years ago (2001), it was accepted wisdom that in the world of priorities you could have two of the three “legs of the stool.” If your focus was on improved care for the individual and improved health for the community, the cost of care had to rise. If you wanted to lower the cost of care and improve the health of the community, you could expect that the quality of the experience of care for the individual would fall. Truth be known, most clinicians were focused on their own priorities and economic self-interests and the Triple Aim was of little interest to them. An enlightened minority of practitioners and delivery systems were focused on quality, safety, and the experience of care. It was the rare clinician or system that endeavored to try to follow the suggestions that would improve all three legs of the Triple Aim. When the pandemic hit the outcome was that we were woefully unprepared as a national healthcare system to take on a public health challenge.

Over the last twenty years, the system has performed very well in terms of its primary objective which is to protect revenues for suppliers of the components of healthcare like medical devices and drugs. Physician incomes have done OK even though a PCP may earn less than a fourth of what an interventionist or a surgical specialist may earn. I present the fact that there are plenty of interventional specialists and surgical specialists working in systems of care for underserved populations (DSH hospital systems) who earn seven-figure annual salaries. The justification is that those salaries are driven “by the market,” and it is true. If a neurosurgeon or orthopedic surgeon can earn a cool million a year at any hospital why would that person take a job for a mear 500K at a DSH hospital that needs neurosurgeons or orthopedic surgeons with a focus on trauma to maintain its status as a level one trauma center?

The market drives the “fair” compensation. Successful institutions must integrate scarce professional resources. The first level of concern is their cost of the personnel, the equipment, and the building and maintenance of the physical assets that are necessary to be in business. They work in a system of finance that was not designed to produce efficiency. It evolved to maximize revenue. The real cost of healthcare can not come down through competition if the competitive problem that must be solved first is the complexity of the market for the scarce and expensive resources necessary to provide services. The problem for rural health systems is even greater since their competition for these scarce human resources is not with another academic medical center across town but with the academic medical center seventy-five miles away in an urban location that offers healthcare professionals a more exciting lifestyle opportunity than a post-industrial small town in a rural setting that has boarded up storefronts on Main Street and is losing population as residents give up the struggle to exist in a failing local economy and are moving away.

I am not surprised that as we increase our focus on public health, and as concerns about hospital and practice finance increase during the pandemic, our interest in the cost of care goes down. We were not ever really convinced that it made much business sense to focus on the cost of care despite the fact that we spend 3.8 trillion dollars a year on healthcare. Any attempt to contain costs is not driven by the concern for the cost of care to consumers or payers, it is to improve profitability. Savings drop to the bottom line.

3.8 trillion makes our system of care the fifth largest economy in the world, larger than the economies of Germany, India, and the United Kingdom. As that fact sinks in, let me say that our cost of care is not something that we should blow off. Our care costs are increasingly borne by consumers through higher out-of-pocket costs, and there is evidence that as out-of-pocket costs go up consumers avoid care, and disease rates and death rates rise. Professor Amitabh Chandra of Harvard, a healthcare economist that I have known, has recently published with colleagues the study at the end of the above link that shows that an increase of $10 per prescription led to an increase in death rates among the affected population because after the cost increase many patients did not fill prescriptions for the drugs that were prescribed.

I learned of Dr. Chandra’s study by listening to a terrific podcast, episode #114 of “Creating A New Healthcare, “Reducing the Costs of American Healthcare – One Percent at a Time, with Zack Cooper, Ph.D.” that was produced by my friend and former colleague Dr. Zeev Neuwirth who is now the Chief Clinical Executive for Care Transformation and Strategic Services at Atrium Health in Charlotte, North Carolina. Zeev is also the author of Reframing Healthcare: A Roadmap For Creating Disruptive Change. If you go to his website you will see that the previous 114 episodes contain interviews with many of the current leaders in healthcare. Of more interest to me is that Zeev is always finding people who have a lot to offer that I did not know about. He has always been a shortcut to new knowledge. For several years his administrative office was two doors down from mine. He introduced me to Lean and with him, I developed a passion for trying to “reimagine” a system of care that was free of the many business and structural anomalies that frustrate both patients and clinicians. The biggest mistake I ever made in my management career was to encourage him to accept the position that he was offered at what was then Carolinas Health and has now been renamed Atrium Health because its reach has extended beyond the Carolinas.

Zack Cooper is an Associate Professor of Public Health and of Economics at Yale University, where he also serves as Director of Health Policy at the school’s Institution for Social and Policy Studies. Dr. Cooper has proposed and is developing an innovative approach to cutting the cost of care. He readily admits that no one would design a finance system for healthcare that would be like what we have. We made a huge mistake after World War II when we decided to offer tax incentives to employers to provide health insurance rather than follow the advice of Harry Truman and make the federal government the payer for healthcare for everyone. Cooper is practical and knows that no industry has more lobbyists and more vigorously defends the status quo than does healthcare.

He would love it if we could start all over and design a new system of healthcare based on what we have learned, but he is a pragmatist and knows that a grand new design is not politically feasible. What is feasible is a multitude of small changes that add up to real reductions in cost.

Cooper’s primary motivation for lowering the cost of care is the burden that the current system has become for families. He points out that the cost of care for a family of four now exceeds the price of a new Toyota Carolla! His second motivation is that from a business and government perspective what we spend on healthcare crowds out other uses of resources. For example, a one percent reduction in healthcare spending would fund pre-K education for the whole country for a year! One percent of 3.8 trillion dollars is a lot of money.

Cooper has sent out a call to all of the healthcare economists in the country. He asked them to move from a focus on writing academic papers about how bad things are to writing three to five-page policy recommendations that might save 1%. Adoption of several 1% ideas to improve the current system would result in huge healthcare savings. Cooper demonstrated the efficacy of the idea when he introduced ideas about controlling “surprise” medical billing that was passed by Congress last December. You can read his policy paper on surprise medical billing on the website that explains his one percent idea.

I would recommend that you explore Cooper’s website, onepercentsteps.com. There is a one-minute forty-two-second cartoon video at the top of the website that explains the whole idea. It is well worth your time. I am excited about the possibilities that Cooper’s idea makes possible. I know several of the economists and have been on panels with some of them at conferences in years past. More importantly, I know that these economists don’t have a political agenda that is based on self-interest. They have frequent conversions with the Biden Administration.

Joe Biden has made it clear that he does not favor Medicare For All. He is committed to approaching universal care through improvements and expansion of the ACA. He also is increasingly pushing expensive programs and projects that require federal funding. An emerging concern is just how much public debt we can take on as we address infrastructure concerns and public programs to move us toward greater opportunity and equity for all Americans. Dollars wasted on healthcare are dollars that could be used to improve the social determinants of health that could produce a virtuous cycle of benefit where a society that better manages the social determinants of health has lower healthcare costs.

I am excited about this new way of thinking about the cost of care. I have got to believe that Zack Cooper is right that if 27 of our top-notch healthcare economists from our best institutions focus on ideas that will lower the cost of care by 1% there will be huge benefits for us all.

Spring and Mud Season Are Here!

Where I live Spring comes in steps that may or may not coincide with what the calendar suggests. This year there has been a perfect match between the calendar and what is happening. For the last week, the temperature has made it up and over fifty most days. There have been a few days when we hit the mid-sixties with clear skies and light breezes. The snow cover in my yard is shrinking toward north-facing shaded areas and the mountains of snow created by plowing are now shrinking to “foothill” status. I am still looking for my first crocus.

The last three-plus weeks have been difficult for me. Shortly after our last snow near the end of February, I fell hard on my left hip while walking down a steep hill on the road that follows the lake. I was using hiking poles but my attention to the recently plowed roadbed must have drifted for a second and in the twinkling of an eye I went down hard. It has happened before and each time I promise myself, “Never again!” Again seems to return once or twice a year. I laid spread eagle on the lightly traveled road for a couple of minutes while I tried to decide whether or not I had broken my hip. I was pleased to discover that I could stand and after a few minutes, I was delighted to discover that I could continue my journey home. I had the distinct thought that I had beat the odds once again. I always relate my falls to football. You go down hard many times during a game but most of the time you get up and keep on going.

In practice, I often saw patients who complained of severe musculoskeletal pain that they could not explain. I would go over their history from three or four days before the onset of their pain and ask questions that would help them remember an event that was the probable cause of their discomfort. So it was with me. About two or three nights after the fall and at least two four-mile walks I had a terrible night of left sciatic pain. I have never experienced such intense discomfort. No amount of ibuprofen could dent it. I tried getting to sleep in an easy chair, on a couch that is usually comfortable, and even on the floor. I tried ice and heat. Nothing worked. During the day I would get a little better, be encouraged, try to walk, and then have another terrible night. My PCP quickly responded to my Epic message and gave me a six-day tapering course of methylprednisolone that helped so much that I felt “normal” and was probably a little crazy because on the third day I thought that I was cured and walked four miles and felt so good that I jogged the last mile which totally destroyed any benefit the steroids had provided. Since then I have been mostly at rest and just going nuts as I watch Spring roll in. I am getting some PT from a great professional and things are finally looking up.

During my convalescence, I have enjoyed sitting on my deck and looking for evidence of Spring that goes beyond the melting of snow and the evolution of mud. What I am looking for is the evidence of open water on the lake like you can see in the picture that is today’s header that I lifted from a favorite three and a half minute video made by my neighbor, Peter Bloch a couple of years ago called “IceOut” which he republished along with 49 others that he had offered to us in the early days of the pandemic. You can see my house at the lower right-hand side of the picture just above the “sey” in Lindsey. What the video reveals is the hidden wonder of the dynamic beauty of melting ice.

The warmer weather frequently creates morning fog over the lake, especially when it rains. When the fog lifts I look for patches of open water. So far the ice has held. I have got to believe that the ice is melting although I have not yet seen the evidence. My guess is that we have at least a week to go before the ice is out. Ice out and Easter may coincide this year which may mean something. I will also get my second Pfizer dose on Good Friday. I will give that collection of events some thought. The combination must have some cosmic significance. The next event to anticipate after the ice is out is the return of the loons. I can hardly wait.

Be well, enjoy the coming of Spring. Get vaccinated, but continue to use your face mask and observe social distances. It would be a shame to have a COVID mired Spring. That would be worse than sciatica.

Gene