June 3, 2022

Dear Interested Readers,

More Problems Than Power In The Search For Solutions In A Divided Land

In 2007, a few months before I became the CEO of Atrius Health and Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates, Dr. Steven Schroeder’s “Shattuck Lecture” was published in the New England Journal of Medicine. In that lecture, he emphasized how we needed to focus on public health issues including the social determinants of health if we hoped to improve the health of the nation. He began the lecture by saying:

The United States spends more on health care than any other nation in the world, yet it ranks poorly on nearly every measure of health status. How can this be? What explains this apparent paradox?

The two-part answer is deceptively simple — first, the pathways to better health do not generally depend on better health care, and second, even in those instances in which health care is important, too many Americans do not receive it, receive it too late, or receive poor-quality care…

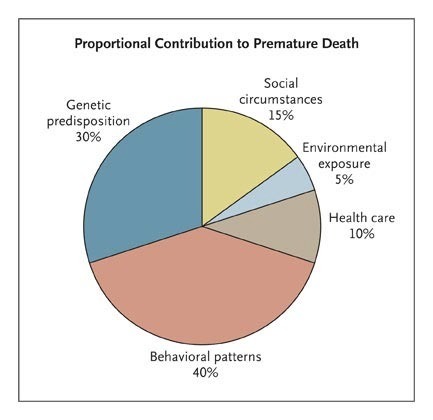

But even in 2007, we all knew that. What we all did not fully appreciate was represented in one of Dr. Schroeder’s graphics. The pie chart below delivered an insight that was a surprise to many clinicians.

Your first observation may be that the chart is not about health, but about the opposite, premature death. You may argue that I am taking some liberty when I use the chart to make observations about how we might improve health. I would counter by noting that the life expectancy of a population is an overall measure of health and that improving life expectancy is an objective of better care. An immediate reaction to a shorter-than-expected life expectancy is to suggest that some problem exists in the organization and delivery of care, but a reflection on the data in the chart shows us that behavioral and social factors may be more important determinants of the outcomes we observe than genetics or the delivery of care.

The second observation is that the primary drivers of a shortened life expectancy are behavioral, social, and environmental issues. Reflecting on that fact, and knowing how much attention and resources we devote to care delivery, testing, research, and treatment of diseases like coronary artery disease, and cancer, it is a surprise that we give less attention and resources to the factors that we now know cause so much premature death. The explanation may be that it is all a matter of finance. Our attention is directed toward what we get paid to do. In a fee-for-service medical world, we don’t get paid to improve the social determinants of health.

In retrospect, I am not sure that even Dr. Schroeder fully appreciated the importance and the implications of the insights his pie chart demonstrated. Here was his primary focus:

Health is influenced by factors in five domains — genetics, social circumstances, environmental exposures, behavioral patterns, and health care. When it comes to reducing early deaths, medical care has a relatively minor role. Even if the entire U.S. population had access to excellent medical care — which it does not — only a small fraction of these deaths could be prevented. The single greatest opportunity to improve health and reduce premature deaths lies in personal behavior. In fact, behavioral causes account for nearly 40% of all deaths in the United States…

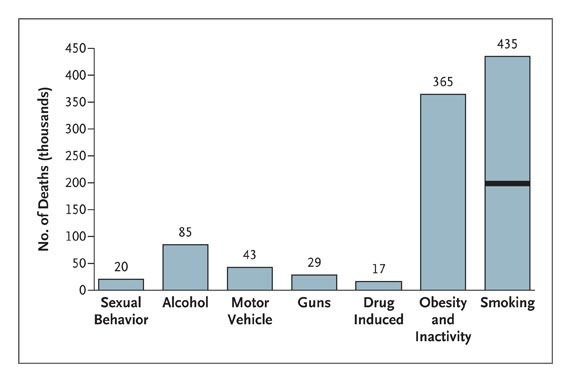

The behavior that got his greatest attention was America’s problem with overeating. He compared the epidemic of obesity to our problem with smoking. His lecture was more than half over before he got around to what we now call the “social determinants” of health and comments about the extra health challenges of the “less fortunate” who have a “lower socioeconomic status.”

Improving population health will also require addressing the nonbehavioral determinants of health that we can influence: social, health care, and environmental factors…With respect to social factors, people with lower socioeconomic status die earlier and have more disability than those with higher socioeconomic status, and this pattern holds true in a stepwise fashion from the lowest to the highest classes. In this context, class is a composite construct of income, total wealth, education, employment, and residential neighborhood. One reason for the class gradient in health is that people in lower classes are more likely to have unhealthy behaviors, in part because of inadequate local food choices and recreational opportunities. Yet even when behavior is held constant, people in lower classes are less healthy and die earlier than others. It is likely that the deleterious influence of class on health reflects both absolute and relative material deprivation at the lower end of the spectrum and psychosocial stress along the entire continuum. Unlike the factors of health care and behavior, class has been an “ignored determinant of the nation’s health.”

A little further along he offered a hypothesis to explain his data:

But aren’t class gradients a fixture of all societies? And if so, can they ever be diminished? The fact is that nations differ greatly in their degree of social inequality and that — even in the United States — earning potential and tax policies have fluctuated over time, resulting in a narrowing or widening of class differences. There are ways to address the effects of class on health. More investment could be made in research efforts designed to improve our understanding of the connection between class and health. More fundamental, however, is the recognition that social policies involving basic aspects of life and well-being (e.g., education, taxation, transportation, and housing) have important health consequences…When public policies widen the gap between rich and poor, they may also have a negative effect on population health. One reason the United States does poorly in international health comparisons may be that we value entrepreneurialism over egalitarianism. Our willingness to tolerate large gaps in income, total wealth, educational quality, and housing has unintended health consequences. Until we are willing to confront this reality, our performance on measures of health will suffer.

What is as remarkable as what Dr. Schroeder does say in the light of what is going on in our world today is what he does not say. He never used the words race, poverty, or mentioned guns or drugs in the body of his speech. The word “poor” shows up once. He did use terms like “less fortunate” and “lower socioeconomic class.” He did include guns and drugs in one of his graphics without referencing them in the body of his presentation. Did he avoid race and use sanitized terms for poverty because he felt they would generate pushback or some “backlash” from his audience?

In 2007, when I first reflected on the message of his pie chart, I felt as impotent as Dr. Schroeder to address the social determinants of health I remembered the scripture, “The poor you will always have with you” (Matthew 26:11) which is a much misunderstood and misused verse. I realized that he was saying that if we removed all of the barriers to care with universal access while maximizing the quality of our care and mitigating all the genetic predispositions that we currently can treat, we would still be faced with huge inequities and substantial health problems unless we effectively addressed poverty and economic inequities.

My internal response was, “Do what you can do.” The improvement of the delivery system and enabling the push for universal care by lowering the cost of care were things that our organization could do directly. We could try to improve our behavioral health offerings and advocate for improvements in the social determinants of health, but measurable success would require resources and political changes that exceeded our reach. We could be advocates, leaders, participants, and partners, but any chance for success would require nationwide participation which seemed unlikely to happen soon given our deep partisan divisions. Perhaps that was a self-serving rationalization.

Looking back more than fifty years, I can say that the environmental concerns of most practicing doctors were pretty much limited to asbestosis and lead, or perhaps industrial exposure to coal dust or textile fibers. Most of us did not focus on environmental issues that were differentially problematic for the poor like food deserts, air pollution, and water contamination with industrial waste from nearby factories. Only a few “tree-hugging environmentalists” and Al Gore who had just recently delivered his “inconvenient truth” in 2006 were talking about how global warming from carbon-based fuels was differentially affecting the poor while it was simultaneously a problem for all of us. Dr. Schroeder failed to address global warming as a public health issue when he expounded on “environment exposures,” but he did recognize that the solutions required political action.

Environmental factors, such as lead paint, polluted air and water, dangerous neighborhoods, and the lack of outlets for physical activity, also contribute to premature death. People with lower socioeconomic status have greater exposure to these health-compromising conditions. As with social determinants of health and health insurance coverage, remedies for environmental risk factors lie predominantly in the political arena.

Toward the end of the speech, Dr. Schroeder did focus on the politics of change. What is sad is that his analysis holds true today:

The comparatively weak health status of the United States stems from two fundamental aspects of its political economy. The first is that the disadvantaged are less well represented in the political sphere here than in most other developed countries, which often have an active labor movement and robust labor parties…Because the biggest gains in population health will come from attention to the less well off, little is likely to change unless they have a political voice and use it to argue for more resources to improve health-related behaviors, reduce social disparities, increase access to health care, and reduce environmental threats.

I’ve mentioned before that I have been reading Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s last book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? (1967). It is sad to say that in the forty years between Dr. King’s book in 1967 and Dr. Schroeder’s speech in 2007, and the fifteen years between Schroeder’s speech and now, not much has changed. On page 86 in a chapter titled “Racism and the White Backlash,” Dr. King writes:

When the war against poverty came into being in 1964, it seemed to herald a new day of compassion. It was the bold assertion that the nation would no longer stand complacently by while millions of its citizens smothered in poverty in the midst of opulence. But it did not take long to discover that the government was only willing to appropriate such a limited budget that it could not launch a good skirmish against poverty, much less a full-scale war.

The social determinants of health were a political problem in 1967, and 2007, and aren’t changed much in 2022. What has changed is that if Dr. Schroeder were to give his speech today his pie chart would need at least two new pieces of pie. We would need one new pie piece for drug deaths and a huge one for deaths from guns. Perhaps between those two, we could also insert the “deaths of despair.” During his impassioned speech last night President Biden announced that guns were now the number one cause of death for children.

It is too early to know whether anything will change in the Senate. My guess is that getting ten Republicans to vote for any form of gun control is as unlikely as MLK knew it was for America to give up its bias toward White Supremacy and offer Black Americans the respect they deserve. I wonder what he would have to say about our arguments over “critical race theory.” I would be delighted with any legislative progress, but I think that the only thing that might be emotionally satisfying or make a practical difference would be a total ban of high-velocity assault rifles and their high-capacity magazines. Australia did it in 1996, and New Zealand did it in 2019. When will we do it? In the interim, I am crossing my fingers and praying that Senators Susan Collins and Chris Murphey might negotiate something that will provide a little hope that things might change.

If anything positive ever happens with either guns or the social determinants of health it will be evidence of a national awakening to the understanding that what we do is much more important than “thoughts and prayers. ” One wonders if we will ever respond to gun violence and poverty with meaningful actions that give evidence to the fact that we finally care about everyone more than we care about the material things we have and personal advantages that we feel might be threatened if we lived in a more equitable society. When that day comes our actions will show that we have given up the deep divisions that cause unnecessary pain and potential personal harm to everyone.

You may read that last statement and say, “Dream on, Pollyanna!” I agree, there will be moss on my tombstone long before assault rifles are tabu and we make sure that everyone has a floor of income, adequate housing, and effective healthcare, but I do believe David Brooks gave us some effective advice this week about how to begin to move in that direction. In reference to the sexual abuse scandal involving many of the clergy in the Southern Baptist Convention, he wrote:

The fact is, moral behavior doesn’t start with having the right beliefs. Moral behavior starts with an act — the act of seeing the full humanity of other people. Moral behavior is not about having the right intellectual concepts in your head. It’s about seeing other people with the eyes of the heart, seeing them in their full experience, suffering with their full suffering, walking with them on their path. Morality starts with the quality of attention we cast upon another.

If you look at people with a detached, emotionless gaze, it doesn’t really matter what your beliefs are, because you have morally disengaged. You have perceived a person not as a full human but as a thing, as a vague entity toward which the rules of morality do not apply.

Character is not measured by a person’s beliefs but by the ability to see the full humanity of others. It is not automatic. It’s a skill acquired slowly. It’s about being able to focus on what’s going on in your own mind and simultaneously focus on what’s going on in another mind. It’s about learning how to minutely observe, absorb and resonate with other people’s emotions.

It comes about through years of shared experiences, decades of other-centered attention, engagement with the kind of literature that educates you in what can go on in other people’s heads. It’s spiritual training to get out of your own egotistic self-referential thinking and into the habit of asking what’s this moment like for that other person…

…We’re living in a period awash in cruelty — not only with abuse scandals, but also with mass shootings, political barbarism and the atrocities in Ukraine…

He ends by saying that we should not expect much help from the clergy, and I would add that politicians probably won’t do much better, maybe even worse. The changes we need for the safety of your child, my grandchildren, and all of those who suffer from the inhumanities that constitute the inequities in our society must begin with the changes in each of us that Brooks advocates. For change to occur we must be able to see everyone as part of one deserving community. Until then…

A Bike Trail Through History

The weather in New Hampshire on Memorial Day was pretty nice. We had plenty of sunshine, the temperature was in the mid-eighties, and the humidity was low. It was the crown jewel of a very pleasant “summer” holiday weekend. The weather has been a downhill ride since Monday. By Wednesday it felt like March again. The temp was in the low to mid-fifties with rain followed by dense fog in the late afternoon and evening. It was a little better yesterday. It was intermittently raining and felt like late March or early April– ditto for today. I am told by the weather app on my watch that the dreariness will end and that the sky will be clear tomorrow and that things will be nice through the weekend and until next Tuesday.

I have learned that the best strategy this time of year is to be prepared to spontaneously seize the moments when the weather is good. So, Monday morning with bright skies and rising temps, I suggested to my wife that we load our bikes onto the rack on our SUV and return to the Northern Rail Trail. My wife had not been on her bike since she fell and separated her shoulder and sustained a deep knee laceration while riding her bike in the coastal redwoods near our son’s home while we were on our RV trip to the West Coast back in the fall of 2020. To my surprise, she said yes.

The Northern Rail trail is the perfect place to return to riding your bicycle after a significant hiatus. It’s flat. There is no traffic, and the scenery is spectacular. If you followed the link you know that the trail is the rail bed of the old Boston and Maine railroad from near Concord up to White River Junction, Vermont. Daniel Webster cut the ribbon to open the railroad in Lebanon in 1847. The passenger service over the route to White River Junction ended in 1965. For over one hundred years the train brought prosperity to the towns along its route.

The old Potter Place Railroad Depot in Andover, New Hampshire is about ten miles from my house and it is the most convenient place for us to access the Northern Rail Trail. Today’s header is a picture of the trail and the old railroad station which was built in 1874. (It’s cloudy because I took the picture on Tuesday.) The station has been preserved and is now a museum and the home of the Andover Historical Society.

Potter’s Place has its own history. Before the railroad came through it was the site of the 175-acre estate of Richard Potter who was an African American who was America’s most famous entertainer in the early 1800s. Potter led an unlikely life. Most Americans don’t know how remarkable his story was, but you can read it on the website of the New England Historical Society, but here are some highlights lifted from their article:

He was born in Hopkinton, Mass., in 1783 to a black mother and a white father. His mother, Dinah, worked as a servant in the estate of Sir Charles Frankland, a descendant of Oliver Cromwell and collector of the Port of Boston. Frankland had fallen in love with Agnes Surriage, a beautiful tavern wench in Marblehead, Mass. He paid for her education and kept her as his mistress. That did not sit well with Boston society, and so Frankland bought land in the distant town of Hopkinton. There he built a showplace mansion.

By the time of Richard’s birth, Sir Charles had died and the estate started to decay. Some people thought Richard’s father was Sir Charles’s son. But it was George Stimson, a randy revolutionary war veteran. Stimson, according to church records, had “made attempts on the chastity of several women.”

One of those women was Dinah. Slavers had captured her on the Guinea coast and sold her on a Boston pier. But in 1769, a slave in Cambridge, Mass., brought suit against his master. He won his freedom and payment for his work. Soon after, Frankland’s estate freed Dinah and her children and paid them for their work.

Potter’s life was fascinating from beginning to end. He had a good basic education in Hopkington and became an apprentice to a merchant in Boston. He traveled to Europe as a servant to the merchant’s son where he began to acquire the skills that would launch his career as an entertainer. He was America’s first widely popular performer. He was an accomplished tightrope walker, magician, ventriloquist, and actor. He took his show to Europe, the Caribbean, and all of the major cities on the East Coast, and even to the South although he avoided Charleston and Savanah. After gaining wealth, he bought his place in Andover in 1814. A friend was the local tavern keeper. In her novel, Peyton Place, Grace Metalious used Potter as the model for her character Samuel Peyton who like Potter was a wealthy Black man who built a mansion in a small New Hampshire town.

The Wikipedia entry on Potter adds the final note of interest:

Potter married Sally Harris in 1808. Potter claimed she was a Penobscot Native American. They had three children. Richard and Sally are buried in a small graveyard on the property he bought in Andover. Their graves were moved but his request was to be buried upright.

What Wikipedia doesn’t tell you is that their graves are just to the left and across the rail trail from the caboose in front of the train station in today’s header. There is an informative marker at their gravesite.

The story on the sign beside the graves is the one I have told you. I like the last paragraph.

Famous for his gentlemanliness, good humor, and courtesy, Richard Potter contributed enormously to the long, gradual process of making American showmanship respectable. As the unsung precursor of the social reformer Frederick Douglass (1818-1895), Richard Potter also demonstrated to an entire generation of Americans that a black man, no less than a white man, could exemplify the best qualities of humanity. He is a seminal figure in American history.

You don’t have to ride the rail trail to visit Potter’s Place. It is just off the highway from New London to Andover, but if you can bring a bicycle with you I would highly recommend it. Even without Richard Potter, the ride would be worth it for the other scenery you see as you glide through the woods, cross the Black River a few times on old railroad bridges, and see other interesting things like covered bridges.

Gas is expensive. So, I advise that you ride a bike or take a walk near home this weekend to see what is interesting near you. It is important to take maximum advantage of every weekend in the summer. By my calculations, we only have fourteen weekends left until Labor Day.

Be Well,

Gene