30 November 2018

Dear Interested Readers,

Hidden Tribes and the Future of Healthcare

Last spring I read The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided By Politics and Religion. It was written by Jonathan Haidt who is a “moral and political” psychologist who studies how people see the world and politics in different ways. He is now a Professor of Ethical Leadership at New York University’s Stern School of Business. Before he wrote The Righteous Mind he had written another important book, The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Truth in Ancient Wisdom. In September he published The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure which he co-authored with Greg Lukianoff.

The recent book was the prime reason that Haidt appeared earlier this week on a lengthy podcast with Ezra Klein, the founder of the online political commentary, “Vox.” I admit to being a Vox/Klein groupie and find his podcasts to be a frequent source of interesting “threads” to follow. The podcast with Haidt is a 90 minute conversation that I have listened to three times now. It is such a rich conversation that I have discovered something new each time that I have listened to it. I suggest that you follow the link above to the program and listen to it yourself. It is the 11/26 program. I enjoyed listening on three separate walks, so load up your smartphone with Ezra and Jonathan and enjoy a physical and intellectual workout.

Last April when I wrote about Haidt’s work my motivation was to try to better understand the mindset of those Trump voters who had voted against what appeared to be their own best economic interest and moral values. I sensed then, and believe even more strongly now, that the future of America depends not on subduing Republicans and other conservatives in elections, but rather understanding where they are coming from and attempting to build consensus for a fairer, kinder, and more successful America through discernment. I know that may sound like the unrealistic world view of a Pollyanna and a surprise, based on the way some of my letters read. I will own up to what sounds like anger, resistance, and a fervent desire to have a new governing majority, but I know from the experience of the ACA that gains from unilateral change are short lived and always at risk. I also know that gains through judicial review, think the Voting Rights Act of 1965, are also vulnerable to reinterpretation when the balance of opinion shifts. The only policies that have some possibility of permanence are those that emerge from shared values.

As a clinician and as a manager, I have always felt that good therapeutics or good management required a deep understanding of the origin of the disease or problem. That was my motivation last April when I wrote about Haidt’s ideas:

Someday the presidency of Donald Trump will be a subject for historians. Whatever historians say, I am sure that they will begin the story long before we thought of Trump’s bid for the presidency as anything more than a joke. The story will not begin with a review of his history of being a reality TV star, or with a review of his life as a playboy real estate developer who was involved in many shady deals that damaged many others as he made what he says was “billions.” Historians will go far upstream and write about the deep divisions in the country that existed long before Roger Stone, Ann Coulter or even Steve Bannon ever fantasized that Trump was “the one.” Trump is a distraction in the real story. The issue that explains Trump is the deep division in America that existed before him and will threaten the country after he is gone. That growing divide within the country between the conservative and liberal mind is the story that produced this moment and produced the unlikely reality of Trump’s presidency and that connection is worth a historian’s interest…

Earlier this year I reviewed Arlie Russell Hochschild’s book Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right. Although it was published before the 2016 election, it was a study of people in Louisiana who could be described as victims of corporate greed who nevertheless consistently, willingly, and with enthusiasm voted against their own personal health and economic best interests. She documented that core values and cultural affiliations “trumped” economics and environmental threats that produced cancer.

I wish that I had discovered Jonathan Haidt’s book The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion long before last month. It was written in 2012. I doubt anyone in Hillary Clinton’s campaign ever read it, or if they did, the message never got up the ladder…

Now that the Democrats have developed a little leverage by gaining control of the House, the big issue is not whether Nancy Pelosi will be the Speaker, but rather how will the discussion about the critical issues change. It is easy to complain about climate change denial, the administrative undermining of the ACA, the treatment of immigrants, the opioid crisis, the falling life expectancy, economic inequality, persistent evidence of unfairness of opportunity toward minorities and the poor in general, as well as our failure to make quality healthcare an easily accessed entitlement. It is another thing to present a positive strategy to make a difference in a way that wins future elections and achieves improvement even before future elections are won or not in 2020. Making progress now and in the future requires understanding and a more effective strategy that is built on the analysis of that broadened understanding of who we are and why we are divided.

The big bonus for me from the Klien/Haidt conversation was to hear them talk about a recently published report named Hidden Tribes: A Study of America’s Polarized Landscape. The report came out just a month ago, but it has already generated a lot of interest. It is 160 pages long, but you can peruse the whole report in an hour once you get the lay of the land. It is full of graphs and insights derived from a questionnaire that is presented as an Appendix. I would suggest reading the introduction and then jumping to the questionnaire before diving into the report. The goal is a deeper understanding of the seven “tribes” that cover the spectrum of American social and political thought. If you are familiar with a Myers-Briggs test there is some similarity here. The Myers Briggs test informs you of how you see the world and interact with it. Before I took the Myers Briggs I thought I was an an INTJ described on the Internet as:

With Introverted Intuition dominating their personality, INTJs focus their energy on observing the world, and generating ideas and possibilities. Their mind constantly gathers information and makes associations about it. They are tremendously insightful and usually are very quick to understand new ideas.

When I took the test I was quite surprised to learn that I was an ENFP. Again the description on the Internet is written to make everyone, no matter their “type,” feel positive about their “diagnosis.” Who knew?

More than just sociable people-pleasers though, ENFPs, like all their Diplomat cousins, are shaped by their Intuitive (N) quality, allowing them to read between the lines with curiosity and energy. They tend to see life as a big, complex puzzle where everything is connected – but unlike Analysts, who tend to see that puzzle as a series of systemic machinations, ENFPs see it through a prism of emotion, compassion and mysticism, and are always looking for a deeper meaning.

In these notes you may have been aware of my self description as a “progressive liberal.” Based on what I read in Hidden Tribes: A Study of America’s Polarized Landscape, I am a more middle of the road liberal.

George Packer, the author of a favorite book of mine, The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America, has recently written an excellent piece for The New Yorker describing “Hidden Tribes.” Early in the article he writes:

Everything in American politics today entrenches tribalism: our winner-take-all elections, the dehumanizing commentary on cable news and social media, the people we choose to talk to and live among. The trends are not new, but they’ve dramatically accelerated and intensified under a President who rules by humiliation because he lives in fear of being humiliated.

As he warms up to describing “Hidden Tribes,” Packer writes a very confessional paragraph that resonated with me:

I hear myself say this [describing today’s problems as the fault of a Republican Party that has lost its way] and think, A solid analysis. At the same time, I hear a Republican reply, “Pure tribalism. You’re just proving your own point.” I want part of my brain, even a small part, to be always attuned to the frequency of other tribes, ready to pose the essential questions: How would this sound coming from them? How do they see you? I try to keep two thoughts in my head at the same time: the other tribe needs to be crushed, and I have to talk and listen to them. The first thrives on rage, the second on tolerance. These are contradictory states of being, and extremely difficult to maintain in tension, but a sane politics requires both. The alternative isn’t victory but self-destruction. After all, we have to live together.

Packer succinctly describes the paper:

Throughout the past year, the report’s four authors surveyed eight thousand randomly chosen Americans, asking questions about “core beliefs”: moral values, attitudes toward parenting and personal responsibility, perceptions of threats, approaches to group identity. The authors then sorted people, based on their beliefs and values, into seven “tribes”: Progressive Activists, Traditional Liberals, Passive Liberals, Politically Disengaged, Moderates, Traditional Conservatives, Devoted Conservatives.

So here from the paper is a more detailed description of the “tribes.” I have added the percent of the population in each group.

The segments have distinctive sets of characteristics; here listed in order from left to right on the ideological spectrum:

– Progressive Activists: younger, highly engaged, secular, cosmopolitan, angry. 8%

– Traditional Liberals: older, retired, open to compromise, rational, cautious. 11%

– Passive Liberals: unhappy, insecure, distrustful, disillusioned. 15%

– Politically Disengaged: young, low income, distrustful, detached, patriotic, conspiratorial. 26%

– Moderates: engaged, civic-minded, middle-of-the-road, pessimistic, Protestant. 15%

– Traditional Conservatives: religious, middle class, patriotic, moralistic. 19%

– Devoted Conservatives: white, retired, highly engaged, uncompromising, patriotic. 6%

The Progressive Activists (8%) on the left and the Traditional Conservatives (19%) and the Devoted Conservatives (6%) on the right are the left and right forces making most of the noise and not willing either to listen or give an inch in asserting their anger or their quest for their ideas to be dominant without modification. They are the “wings.” [They did not say “wing nuts”, that would not promote understanding, but you wonder what they really were thinking.] The hope that the authors see arises from the potential conversations in the middle, collectively called the “exhausted majority,” between Traditional Liberals, Passive Liberals, Politically Disengaged, and Moderates. It is from the interaction of those groups that the nidus of opportunity exists and allows the authors to come to a hopeful conclusion:

This report lays out the findings of a large-scale national survey of Americans about the current state of civic life in the United States. It provides substantial evidence of deep polarization and growing tribalism. It shows that this polarization is rooted in something deeper than political opinions and disagreements over policy. But it also provides some evidence for optimism, showing that 77 percent of Americans believe our differences are not so great that we cannot come together.

The report is interesting reading with many “pearls” that resonate with personal experience that are so obvious that you wonder why they felt the need to write it; like:

Devoted Conservatives have the warmest sentiments towards Trump supporters and NRA members, and the coldest sentiments towards Black Lives Matter activists and Hillary Clinton supporters. Progressive Activists have the warmest feelings towards LGBTQI+ people and refugees, and the coldest feelings towards Trump supporters and NRA members. The feelings of Progressive Activists towards Trump supporters were the coldest recorded for any group.

But then you get the optimism that the study offers:

…Yet Americans are fatigued with all the tribalism. When asked whether the differences between Americans are too big for us to work together anymore, or not so big that we cannot get together, 77 percent of Americans still say the latter.

Later:

The four segments in the Exhausted Majority have many differences, but they share four main attributes:

– They are more ideologically flexible

– They support finding political compromise

– They are fatigued by US politics today

– They feel forgotten in political debate

Data can demonstrate that even on the “wings” there is a little opportunity. That’s why there are 77% of Americans, which includes some from the “wings” who are hopeful.

…Just as they reject the tribal opinions of the political extremes, America’s Exhausted Majority disapproves of the hyper-partisan conflict that has overwhelmed political debate in the United States. Far more than those in the wing segments, members of the Exhausted Majority are willing to compromise and believe that “the people I agree with politically need to be willing to listen to others and compromise” (65 percent). Among Progressive Activists, this number is 56 percent; among Devoted Conservatives, only 37 percent. The Exhausted Majority is also more likely to believe that “we need to heal as a nation” (64 percent) than either of the Conservative groups (52 percent and 38 percent, respectively).

They use their data to reinforce the opportunities for any group that can lead a change in conversation that can capture the imagination of the “Exhausted” majority.

American identity is still most commonly defined by its ideals of freedom and opportunity. Americans are united in believing that a commitment to freedom and equality are important for being American (an average of 91 percent across segments gave these issues a score of 5 or higher on a 7-point scale). Similarly, 73 percent value “pursuing the American dream.” (Notably, however, a full 24 percent of Progressive Activists say that such a quality is “not at all important.”)

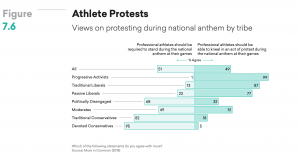

I found several interesting graphics that demonstrate the range of opinion within the seven tribes. Here is a presentation of the data about athletes kneeling during the National Anthem that demonstrates both polarization and possibility,

They offer some strategic comments that should be given consideration if we really want to have productive conversations:

…we need new approaches to show that high-profile debates often misrepresent the views of most Americans, presenting the most extreme and polarizing positions as representative of all Americans. Americans who belong to the Conservative tribes need to hear more of the pride and patriotism of Progressive Activists and Traditional Liberals, just as those groups need to hear how a large majority of Conservatives agree that we are all fully American, regardless of race or religion. This will not remove the need to address real differences that exist over important issues, but by showing the common ground between Americans we might enable progress on those issues.

The obvious reality of polarization that we must try to keep from getting worse is well described:

Polarization has made it increasingly difficult for Americans to engage with each other on the most contested issues of the day. In this context, disagreements sometimes focus less on the substance of an issue, and more on the language used to discuss it. This creates a chilling effect, driving more and more Americans away from public debate and leaving the conversation to the loudest, most extreme voices.

They also present a chilling reality. Our polarization has us all listening only to those who agree with us, and it sells papers, grabs viewers, and has become an indoor sport for many:

It is difficult to break this cycle of polarization. Tribal outrage works as a business model for social media, cable television and talk radio. It succeeds where redistricting has shifted the political contest from the center ground in general elections to the mobilized base in primary campaigns. It is metastasizing from national politics and online forums to campuses, workplaces and the dinner table at Thanksgiving. The well-documented result is that growing numbers of Americans are segregated into echo chambers where they are exposed to fewer alternative ideas, and fed a constant stream of stories that reinforce their tribal narratives. Over time, this environment spawns increasing extremism, as start-up initiatives from political campaigns to new media outlets seek to out compete established players through ideological purity and aggression.

Toward the end of the paper, on page 138, they offer some suggestions for improvement that all of us who want a different political climate should consider:

- – Political candidates can speak to the values that unify the nation with a larger “we,” instead of mobilizing their base while polarizing the country.

- – Activists and advocates can broaden their appeals to the underlying values of those they don’t usually reach.

- – Philanthropists can invest creatively in the thousand points of light that can show us a way forward to counter polarization and develop robust evaluation measures to prove impact.

- – Creative artists and media can spotlight the extraordinary ways in which Americans in local communities build bridges and not walls, every day.

- – Technology companies can turn their vast resources and analytical tools to creating platforms and systems that help do the hard work of bringing people together, rather than the easy work of magnifying outrage in echo chambers and filter bubbles.

- – Leaders in government, business and nonprofits can apply the lens of integration to every context where Americans are brought together – from schooling and town planning to office layouts and volunteer activities, creating spaces that connect people together across the lines of difference.

The conversation about how to have a better conversation is important to the future of healthcare. Healthcare professionals should be leaders in the conversation about improving the “political health of the nation” because a “sick” political environment can never foster an environment that supports the “wholeness” that is necessary for healthy individuals. This week we learned that we lost ground again in 2017 as measured by life expectancy. The causes seem to be overdoses, gun violence, suicide, accidents, and issues related to the poor choices we make including what we chose to eat and how much. Deaths from cardiovascular disease continue to decline and cancer deaths are also improving. We are dying more frequently because of our increasing loss of control over the social determinants of health. How can we improve those “health problems?” Bench lab work with mice and DNA is unlikely to make a difference for these problems. They are amenable to collective efforts that can generate better social and economic policy.

I doubt that we will ever grant reparations for past social wrongs, but we can imagine a more equitable distribution of future opportunity and health through better collaboration across all of “our tribes.” If the Democrats want to get elected they need to begin by understanding how to improve the conversation. If you and I want to be a part of the solution and not a continuing part of the problem, then we must begin to improve our own listening skills and try to develop our own collaborative opportunities. The data suggests that here is a majority coalition that could be built on the similarities of desires within the tribes.

We Have Tons of Snow Before December!

When it comes to weather my memory is often not supported by data. Summers are remembered as hotter, colder, or wetter than records corroborate. I remember snow storms before Halloween and after Mother’s Day. I remember the blizzard of 1977, or was it 1978? My wife reminds me that it was 1978 and she was stranded in California because Logan Airport was closed. She has always regretted missing the experience.

If you have data to prove that there has been more snow in the Sunapee Region of New Hampshire before December, I want to see it. I’ve had a home in the Upper Valley since 1995, and I have seen a lot of snow but never this much, this soon. We were “supposed” to get as much as six inches of snow Monday night but by the time the eleven o’clock news was over we were beyond seven or eight and moving toward fifteen, as you can see in the picture that is today’s header which was taken mid morning on Tuesday as the snow continued to fall. This last dump, added to the residual six or so inches from two or three earlier, more modest accumulations. The products of these storms and the efforts of the guy who plows my drive are several huge piles of snow around the parking area at the end of my long drive that are pushing seven or eight feet in height. They form a base for my own ski area. What is amazing is that the trees remain “frosted” with snow now several days after the storm.

It’s a good thing that I like snow because this winter looks to be a snow bonanza. There are some who say it is too early to tell. I was reminded by a friend that within the last decade we had a lot of snow in November and early December before going into a draught with no more snow until late February, and not much after that. Every winter is an adventure story, but some stories have more interesting plot twists than others. This one is off to a good start and could be shaping up to be a classic.

Be well, take good care of yourself, let me hear from you often, and don’t let anything keep you from doing the good that you can do every day,

Gene