August 25, 2023

Dear Interested Readers,

The Continuing Story

If you have not read this letter in the past few weeks, let me inform you that I have been on an autobiographical journey. The trip began as a reflection on moral injury in medical practice. I have been occasionally writing about moral injury since 2015. This round of consideration began when I came across an article written by Eyal Press in the Sunday New York Times entitled “The Moral Crisis of America’s Doctors: The corporatization of health care has changed the practice of medicine, causing many physicians to feel alienated from their work.”

So, what is moral injury? The term as applied to healthcare was adapted from a military origin. As Press writes:

In July 2018, Dean published an essay with Simon G. Talbot, a plastic and reconstructive surgeon, that argued that many physicians were suffering from a condition known as moral injury. Military psychiatrists use the term to describe an emotional wound sustained when, in the course of fulfilling their duties, soldiers witnessed or committed acts — raiding a home, killing a noncombatant — that transgressed their core values. Doctors on the front lines of America’s profit-driven health care system were also susceptible to such wounds, Dean and Talbot submitted, as the demands of administrators, hospital executives and insurers forced them to stray from the ethical principles that were supposed to govern their profession. The pull of these forces left many doctors anguished and distraught, caught between the Hippocratic oath and “the realities of making a profit from people at their sickest and most vulnerable.”

There is no doubt that today’s healthcare professionals face many great stresses in the performance of their professional responsibilities despite the fact that we possess skills and understanding that far exceed what existed when I entered medical school and even what we knew and had within the last few years. The admittedly stressful environment has led to what is considered to be an epidemic of professional “burnout.” It is my sense that we often posit the origin of burnout in the “doability” of the job and the failure of some to have the stamina, skill, or desire to match the challenges of the moment. Attempts to address the problem have usually been directed at strengthening or treating the emotional “inadequacies” of the professionals or in more enlightened environments, improving the system parameters of the workplace.

The Times article suggested that much of what we call burnout is actually “moral injury” that is “an emotional wound sustained…in the course of fulfilling their duties,..that transgressed their core values. So, how often in practice are our core values transgressed? The article got me thinking once again about my own experience in healthcare and the origin of my “core” healthcare values. I suspect that for many of us, our professional values arise from multiple influences. In a way, we are back to the question of “nature versus nurture.”

I can only speak for myself, but I am not against the idea that what shaped me might also have been similar to the experience of others with some minor variations. I assume that genetics, family of origin, community, education, personal relationships, unique events, and the experience of professional training have been contributors to whom we are professionally, our resilience in difficult times, and our moral sensibilities.

My original piece on moral injury in 2015 grew out of a confession from a dear friend and former colleague who had left our practice for a position on the West Coast in the mid-eighties. Our friendship has been strong enough to survive for forty years across a continent. In 2015 the occasion was an extended visit with us after he and his wife had come East to attend our youngest son’s wedding.

I had thought for thirty years that he had left our practice and returned to the West Coast where he was raised and attended Stanford because of issues with his elderly parents and the desire of his former wife to leave Boston. I had blamed her for my loss of the pleasure of my frequent philosophical conversations with him. You can read the story in detail by clicking on the link, but the short version is that we were sitting on my dock chatting with my neighbor in the early evening after a tour of our lake on his boat. After explaining our prior relationship in healthcare to the neighbor, I brought up how upset I had felt when he left Boston in response to what I thought was the insistence of his ex-wife. He quickly corrected me. He described in great detail how injured he had felt when he lost a patient through the failure of the way our practice was at times dependent on the support of the systems at the Brigham which was the hospital where we had both trained and where our patients were hospitalized.

I recount the story to emphasize the element of chance that can create a different “moral” experience for two individuals in the same practice who in all other ways appear to be quite similar. I believe that the best thought to underline before moving on is that moral injury is very personal and the circumstances that can precipitate a sense of moral injury can vary from individual to individual. To paraphrase Justice Potter Stewart’s comment about knowing pornography when he saw it, I will sum up my feelings about moral injury and say that those like my friend who have experienced it know it when they feel it. Press’s article suggested to me that many of those whom we would label as “burned out” are actually the victims of moral injury. When we see their distress and call it burnout we sometimes infer that they were not strong enough to endure the challenges of today’s practice environment. Instead, they are demonstrating a response that more of us should have and could have if we looked at what we do through the lens of the impact of today’s healthcare on vulnerable patients rather than just thinking about how hard it is for us.

The exercise of reviewing my experience in becoming a doctor may or may not explain to you my own outrage at the shape and state of our current healthcare system that fails so many people, but I will continue the story. Perhaps it will partially explain my own growing sense of moral injury or personal failure that has resulted from many years of inadequate efforts to help reshape a distorted system of care that has perpetuated many of the inequalities of our society and failed to be the force that could drive improvements in the social determinants of health that could save us all from future misery.

As others have, I would sum up my medical school experience as a “huge vocabulary lesson,” and add that it was also a long preview or the first step in the continuing cycle of “See one, do one, teach one” which felt to me like it was the core principle of medical education. Factiously, and based on personal experience, I have often thought that the reality was “See one, fail (or screw) one, then do one, after which you are ready to teach one.” In the hospital and in the clinic it is a reality that the inexperienced are often trained by the recently experienced person who is just one rung higher on the training ladder.

What follows is a description of roles, responsibilities, and realities that existed in the early seventies when I was in training. As a medical student, I spent a lot of time watching interns and residents while hoping or fearing that I would be granted more opportunities. We were like rookies, who often struck out when we got our first turn at bat. We were primarily learning from “our intern.” We were exposed to the junior and senior residents, the chief resident, and our attendings, but they were more distant figures who seemed to have the responsibility of continually demonstrating the holes in our funds of knowledge by means of the Socratic method of asking questions that we couldn’t answer.

As an intern, I felt that I was sandwiched between the medical students for whom I was like a slightly older sibling, and my junior or senior resident for whom I was like a younger sibling. Your internship is the year of your maximum direct authority in the care of the patient. You are empowered to decide which tasks, often called scut work, to give to the medical student, and what to keep for yourself to do. A very good intern can be a joy for the resident because the primary role of the resident is to be a supervisor who is a fail-safe of medical knowledge and skill, but is one step removed from the patient and lets those below learn by trying, failing safely, and ultimately succeeding.

The chief resident is like the general on the hill watching the battle but knowing that his/her direct opportunity to make a difference is limited. It is the role of the chief resident to observe and extract experiences that can be used later as teaching comments. The chief resident and chief of our medical service conferred with all of the team leaders who were the junior and senior residents at “morning report,” a meeting where all the new cases from the day before were briefly presented and discussed.

During my internship at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in 1971-72, the great endocrinologist, Dr. George Thorn was in his last year as Chief of Medicine. He became the Chief of Medicine in 1942 at the age of 36. You should click on the link to review his remarkable career.

My Chief resident was Dr. Michael Lesch who later was a professor of cardiology at Northwestern. Mike was “famous ” as a medical student at Columbia where he and one of his advisors published a paper that led to his name being attached as an eponym to a disease. He is the Lesch of “Lesch-Nyhan” syndrome.

I worshiped Mike. He was what is called a “mensch.” He was enthusiastic, and passionate about the care of the patient. I saw Mike most frequently when he would casually stroll by where I was working late at night just to chat and see how I was doing. I assume he did the same for all of the other interns. One terrible night when I was the intern on E2-F2, the female ward service, I was struggling with a heavy load of new patients. The room across from the nursing station is where the most severely ill patients were placed. That night the sickest person was a 27-year-old woman with three small children who was painfully dying from acute myelogenous leukemia that was beyond even short term relief. Blood was coming from everywhere and she was blinded by bleeding into her eyes. There was only one thing to offer her, morphine. I had never been in such a situation before and was giving her just enough of the drug to keep her intermittently barely comfortable. Mike assessed the situation and told me that if she could respond to my voice at all, I was not giving her enough. After we left her room, he said, “Gene, if she is with us in the morning I am going to think that you didn’t give her enough help.” When the sun came up she was still suffering, and I felt like a failure. She lingered until later in the day when mercifully her ordeal ended.

Dr. Eugene Braunwald succeeded Dr. Thorn in July 1972 at the start of my junior residency. For the last fifty years, Dr. Braunwald has been one of the most powerful men in American Medicine, and the editor of the most prominent textbook of medicine. So, for the next two years, when he was in town, Dr. Braunwald took most of the morning reports I attended. After “morning report,” we would have “Attending Rounds.”

In my experience, the role of the Attending Physician on the team had the greatest ambiguity. In my day, for “ward services,” the Attending Physician was the legally responsible physician of record for patients. Patients admitted to one of our ward services did not have a private doctor. They often were “clinic patients” and after discharge were often followed in the clinic by the intern to whom they were assigned during their hospitalization. Over my three years as an intern, junior resident, and senior resident, I built a large clinic practice. When I went to work at Harvard Community Health Plan about a mile away from the Brigham, several of those patients followed me.

Although the Attending was the physician of record, his role was to teach. (Never in my experience at the time was the “Attending” a woman.) Attendings usually were assigned to a team for about a month. During that time they were present for teaching rounds every morning of the week but Sunday. During the “Attending Rounds,” the patients who had been admitted the day before were the primary focus, although important events and problems in the care of any patient might be discussed and advice offered.

Perhaps, some time since about 2007 when I last served as an Attending, or perhaps since 2008 when I last made hospital rounds on my own patients, things have changed, but what I experienced had been a culture that had been constant for many years. It was a proven method of imprinting medical trainees with very similar “core values.”

Now that you have an overview of the training scheme that forms the bridge between medical school and a specialty fellowship or medical practice, stay with me as I briefly describe my experience applying for my internship and its beginning on June 20, 1971.

As I wrote in a recent letter, the Children’s Hospital Family Health Program was one of the high points of my medical school experience. I learned that I really enjoyed longitudinal care and the relationships it created. Becoming part of someone’s life is an honor. The surgical experiences that I described last week informed me that despite my original attraction to the idea of being a surgeon, I was not meant to be one.

When Dr. Joel Alpert who led the Family Health Program at Children’s left to become the Chief of Pediatrics at the Boston City Hospital the future of the combined program leading to board eligibility in both medicine and pediatrics between Children’s and the Brigham became uncertain. Without Dr. Alpert, I was worried about applying to the program. I decided that the best route for me was an internship in medicine.

I don’t remember how I got the information that my academic record made me a candidate for an internship at an elite hospital, but I was on track to graduate with honors and had been encouraged to apply for an internship at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital where I had my medical school rotation in medicine. I also applied to the Harvard Service at the Boston City Hospital, and the Mass General since I had several medical school rotations in both of those institutions. In the end, I also applied to The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, The Hospital of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and to Strong Memorial Hospital in Rochester.

My first interview was at the Mass General. The committee asked me lots of questions about my plans for the future, and then some specific questions about diabetes management. In my answer, I focused on the social concerns of management and the public health concerns rather than the acute management of diabetic ketoacidosis. I saw eyes roll, and I made a note to myself that I should stick to science and basic steps of acute management when answering interview questions in the future. A week or so later when interviewed by a similar committee at the Peter Bent Brigham, I stuck to answers that were almost verbatim from The Washington Manuel or Harrison’s Textbook of Medicine avoiding any comments at all about the psychosocial aspects of care. The strategy must have worked because on Match Day I was delighted to learn that I was headed to the Peter Bent Brigham.

“Match Day” is a tough day whether you get exactly what you want or discover, as a few classmates did, that you did not match. Those that did not match worked with one of the associate deans to find an acceptable assignment. I had the sense that over the years the Dean’s office had cultivated some relationships for such a situation which were in fine hospitals in less desirable geographic locations. In the end, everyone was going somewhere, but it is hard to enjoy your own good fortune when you know that someone you care about is dealing with great disappointment.

It is amazing to me that I have no concrete memories between the end of the semester and the first day of my internship. I must have moved because we had to leave our apartment in Peabody Terrace which is Harvard University housing for married students. We found a nice little house to rent in a Newton neighborhood which had been originally developed after World II as veterans’ housing and in recent years had become popular with married interns and residents in the Longwood Medical Area. With my family moved and settled I was ready to begin the next step of my journey on June 20, 1971.

We were gathered in the Houseofficer’s Lounge high above the lobby of the old Peter Bent Brigham Hospital. It was a room from an earlier day with overstuffed leather furniture and a large fireplace that looked like it had not been used in years. Hanging over the mantel of the fireplace was a portrait of Dr. Soma Weiss, the second Chief of Medicine at the Brigham who had died on rounds at age 43 in 1942. The story that I was told was that Dr. Weiss announced to the team of medical students, interns, and residents that he was rounding with that he had just suffered a ruptured cerebral aneurysm and would die within a few hours. He made the correct diagnosis, and his fate was as he predicted.

Perhaps my memory is flawed and the picture over the fireplace was of Dr. Merrill Sosman, a pioneer of radiology whom I was told once proclaimed that x-rays would make the stethoscope a historical artifact. There were portraits all around the hospital everywhere one looked of famous doctors. One had the sense that these famous physicians had set standards of medical values and practice that one should strive to emulate. The frequent challenge of those standards in one’s professional life could indeed cause “moral injury.”

As mentioned above, Dr. George Thorn who was chosen to follow Dr. Weiss was even younger and similarly brilliant. Dr. Thorn, who always looked young and energetic, welcomed us as the last group of interns of his long tenure. He gave us an overview of the hospital’s history and culture before turning the meeting over to others to add their own words of welcome.

The most memorable event of the morning for me was the little speech given to us by another grand old man of the Brigham, Dr. Lewis Dexter, one of the pioneers of cardiac catheterization and authority on pulmonary embolisms. (I met my wife a few years later when I rotated through Dr. Dexter’s cath lab where she was the head nurse.) The link above is a brief bio from the NIH and the National Library of Medicine. It is well worth your attention, but there is one paragraph that resonates with me as very true based on my many close experiences with him during my years of training.

During a teaching exercise, Dexter demonstrated that exercise with a cardiac catheter in the heart was safe and produced clinically important data, by having a cardiac catheter inserted in himself. Over the years, many significant pathophysiologic studies that explored pulmonary embolism, valvular heart disease, right and left ventricular function, and pulmonary hypertension were published from Dexter’s laboratory. But Lewis Dexter was more than a brilliant researcher. “Lew” was very close to his fellows and students, whom he considered extensions of his family. Dexter was a remarkable teacher, a compassionate physician, and a scrupulously honest investigator. Dr. Lewis Dexter had a major impact on modern medicine and was one of the great cardiologists of the 20th century.

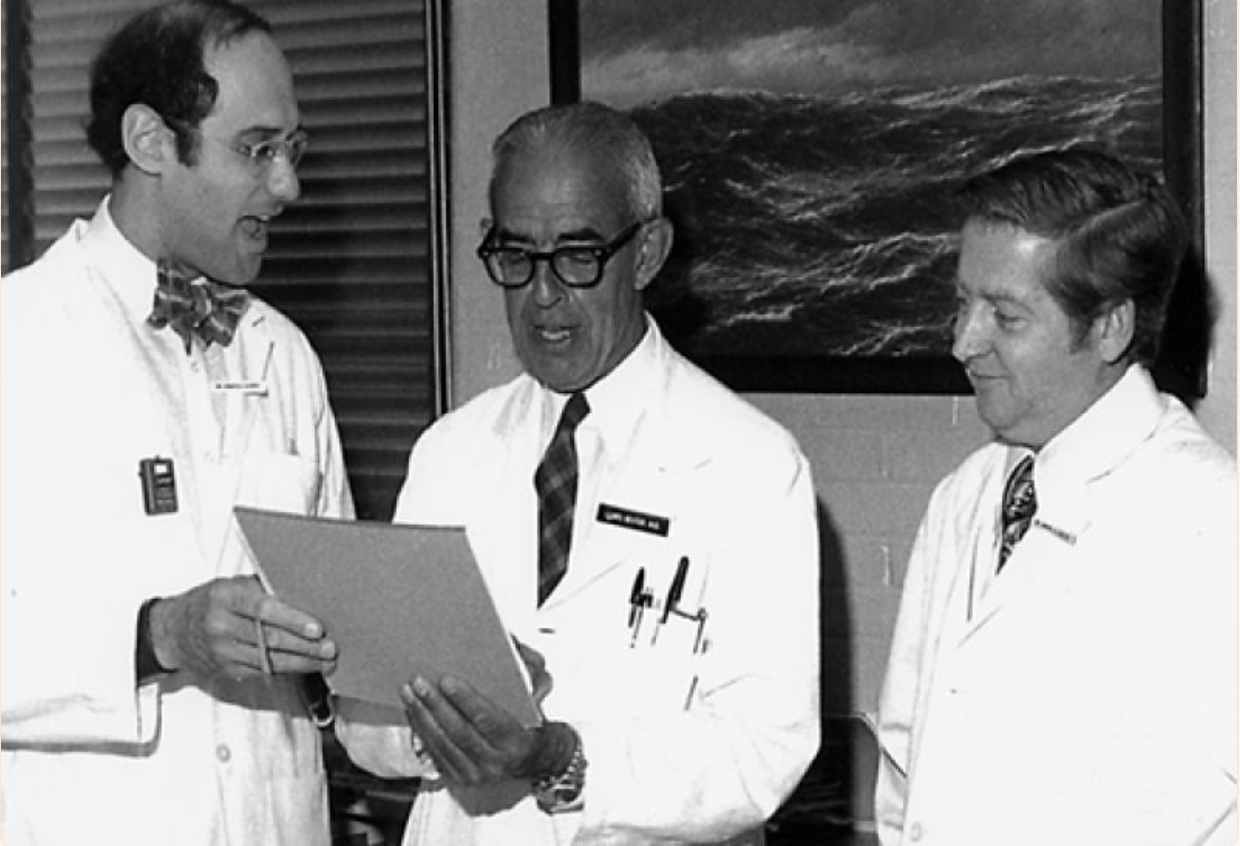

The article contains several pictures, including the one below of Dr. Joe Alpert (not Dr. Joel Alpert, the pediatrician mentioned earlier) who worked in Dr. Dexter’s lab, to Dr. Dexter’s left, and to his right, Dr. Jim Dalen, the director of Dr. Dexter’s cath lab and later Dean of Medicine at the University of Arizona. Dr. Alpert and Dr. Dalen were trained by Dr. Dexter and shared his incredible teaching skills. I was introduced to hospital medicine as a medical student by Joe when he was an intern and enjoyed Dr. Dalen as one of the most effective attendings I ever experienced. Dr. Alpert and Dr. Dalen were great cardiologists and also had substantial expertise in every aspect of medicine and practice. I especially remember Joe as a brilliant, compassionate man, with an outrageous sense of humor and theater. He was a performance artist that made medicine fun. It was men like Dr. Dexter, Dr. Alpert, and Dr. Dalen that made the Pent Bent Brigham Hospital of the early seventies such a great place to learn and to be imprinted with practice values that fifty years later are so often challenged by our current system of care

On that June morning in 1971, Dr. Dexter tried to give us a picture of what we could expect over the next year and over our future careers. What I remember most from his little speech and have reflected on many many times since was his emphasis on the importance of searching for certainty about “the diagnosis.” He said that if you knew the diagnosis you knew exactly what needed to be done. Without a diagnosis that you could trust you would be floundering. The art of medicine was to know how to proceed when you did not know the diagnosis. He was absolutely right!

The perfunctory part of the initial meeting was our first assignment. To my surprise, I was assigned to the men’s ward service on F Main. The ward services were the most challenging rotations. After learning that I was headed to F Main, I was told that it would be my first “night on call.” Besides being in the last group chosen during Dr. Thorn’s tenure, I was also in the last group for whom the internship was an every-other-night on-call experience. There were fourteen interns and fourteen rotations, and all but two had every other night on-call responsibilities. If medical school was a big vocabulary lesson, the internship was an exercise in sleep deprivation and endurance.

I walked down to F Main with my resident and the other intern, a fellow named Doug, who was older and had a PhD in renal physiology. It was a long day. I did not sleep. All day and through the evening into the late night the “admissions” just kept coming as I was trying to get familiar with the patients I had inherited from the intern who had just completed his year and was heading out on vacation before starting his junior residency on July 1. What was most memorable about the first twenty-four hours of my internship was sitting at a desk in front of a window at the nursing station writing orders while realizing as I saw the dawn coming that I had never gotten to bed, and I was not sure how I would get through the next twelve or fourteen hours until I could go home. In my near stuperous state, I did not fully realize just how challenging an experience this process of becoming a doctor was going to be.

Fall Temps With Flowers

I am now swimming in my wet suit again. The temps at night this week have been as low as the high forties and the daytime temps are mostly in the low seventies. The water feels quite chilly, especially when it is overcast and windy. I wish that some of that Southern heat that I hear about on the evening news would move our way. The high today may not make it to seventy. Most of the day will be in the sixties with overcast skies and rain. I don’t mind swimming in a gentle rain as long as there is no thunder and lightning.

There have been some very nice days even though the water is cold. The humidity has been low, and on some days we have enjoyed very bright skies with a few beautiful puffy white clouds. The flowers have been glorious. In our front yard, the phlox and a big bush of Rose of Sharon are in full bloom. I like that the Rose of Sharon waits till August to bloom. As you can see in today’s header, the blackeyed susans and coneflowers dominate the lake shore in the backyard.

I hope the weather will be fine where you will be this weekend, and that there will be plenty of flowers to dazzle you!

Be well,

Gene