One of my favorite experiences is getting an email from an old friend and colleague. Better yet is getting an email from an old colleague who is still an “interested reader.” The “trifecta” of experiences associated with an email from an old friend and colleague who is an “interested reader” occurs when that friend/old colleague and “interested reader” tacks on an informative reference for me to read and ponder.

Rob Jandl presented me with that trifecta late last Saturday afternoon. Rob was the medical director at Southboro Medical Group which was part of Atrius Health while I was there. Over many shared experiences, we developed a strong relationship that was built on a foundation of shared personal and clinical values. If someone were to ask me to name a physician whom I thought best embodied the spirit of Francis Peabody’s admonition that “the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.” I would immediately respond, Dr. Rob Jandl.

With their overlapping service areas in the far western suburbs of Boston and Central Massachusetts, Southboro and Reliant Medical Group in Worcester, which also became a part of the Atrius family, were natural partners. Eventually the two groups joined forces and left Atrius to pursue what would become a challenging independent partnership. In 2018 Optim Health, which is owned by United Healthcare, purchased Reliant and Southboro after promising significant capital to upgrade staff and facilities. Through all the transitions, Rob and I had stayed in touch, but it had been a while since our last contact. I was eager to read about what Rob had been doing in the interim. I was delighted to see that it was a long letter. It began:

Gene,

It’s funny, I feel like we are staying in touch since I get your weekly missives and philosophies, but it really doesn’t work that way does it? This year, I am making more of an effort to stay connected, and well, like it or not, you are on that peculiar accounting. I have dreamy images of you sitting by the pond looking out at the ice or the hills or the foliage or the water fowl while composing and thinking, and think that an elegant and comfortable retirement…

After some updates on his current activities and some family news, he continues:

…The Optum journey is still young, but interesting…the alignment around value and doing the right work is strong. We recently listened to a presentation by Jeff Brenner on homelessness and healthcare that was inspiring. He came to Worcester as an employee of United Health. I am sure you know him but here is a link to a related article.

So I like that side of things…

Rob was right. I did know of Dr. Brenner and I have heard him speak. If you are a fan of the writing of Atul Gawande you also know of Jeff Brenner, who is a MacArthur Grant recipient, who first gained national prominence after his work was reported by Gawande in a famous New Yorker article, “The Hot Spotters: Can we lower medical costs by giving the neediest patients better care?” The piece came out nine years ago in January 2011. It remains my favorite Gawande article.

The link above to Brenner’s 2013 MacArthur grant gives us a very nice capsule of what Gawande described with more flare in his article. They wrote:

Jeffrey Brenner is a primary care physician creating a health care delivery model to meet the medical and social service needs of the most vulnerable citizens in impoverished communities. Determined to improve the lives of the sickest residents of Camden, New Jersey—one of America’s poorest cities—Brenner constructed a searchable database and geographic mapping of discharge data from all patients at Camden’s hospitals and discovered that a very small number of patients consumed a large share of the overall costs of health care and social supports.

To address this issue, Brenner established the Camden Coalition of Healthcare Providers, bringing together doctors in community-based private practices, frontline hospital staff, and social workers across the city to participate in a strategy of comprehensive preventive and primary care. He designed a system that delivers daily information about hospitalizations to the Coalition and members of Care Management Teams. Each team is made up of a registered nurse, one or two licensed practical nurses, a health coach, and a social worker to support and help coordinate care for patients with complex medical, and often social, issues.

The “color” of Gawande’s article provided many of us the hope that by using data and team based care we could simultaneously improve the lives and health of some of the most socially and medically challenged members of our community. It was an example that led me to believe that the promise of the Triple Aim could become a reality. Brenner’s work was an example of better care for the patient, a healthier community, and a lowering of medical expense through a more focused and effective use of resources.

Brenner tells his own story best In a “Ted Talk” that he gave in 2015. In the talk he lays out the situation he faced, and the strategy he used as he tried to face the challenge. It was indeed an approach that suggests “genius.” It is yet another example of the wisdom of “following the money.” I would suggest that you follow the link and invest the time to hear the story. He had tried to be a caring family physician in one of the poorest cities in America. Most of his patients were on Medicaid, and he discovered that it was impossible to provide adequate care on the funds that were available through a fee for service Medicaid practice. He reasoned that there was plenty of money in the system, but the data he began to collect showed that the money was being spent in the local hospitals after avoidable issues had gone untreated. As the MacArthur Grant citation reports, he organized a better system of care to try to make a difference. In the circles in which I traveled Dr. Brenner had become a “rock star.” Here is a picture of the storefront practice from which Dr. Brenner launched his efforts to improve the health of many of Camden’s most challenged citizens.

The reference that Rob gave to me from Bloomberg Businessweek tells the next chapter in the story of the evolution of Dr. Brenner’s story of using clinical innovation to improve the care of the patient in the spirit of the Triple Aim through an understanding and application of the principles of population health. I was quite surprised when I learned from Rob that Dr. Brenner was working for United Healthcare, the largest health insurance company in America with a market share of over 14%, which is enormous considering that Anthem/Blue Cross and Aetna together are only 18%. For those who don’t know the family relationships in corporate medicine, Optum, the company that bought Reliant Medical Group, is United’s entry into medical practice ownership.

Dr. Brenner’s genius has brought him a long way from a store front solo practice in one of America’s poorest urban environments to the highest level of management in one of America’s most successful publicly traded corporations that is comfortably sitting at number 6 on the “Fortune 500” list with revenues of over 200 billion dollars in 2017.

With my prejudices against large corporations owning “for profit” practices of medicine, I was surprised to hear that Dr. Brenner had gone over to “the dark side,” but I am not a Pollyanna. He is just the latest well known physician of intellect and insite who seems to think that corporate America will be very influential in the future of medicinal practice. Atul Gawande is the CEO of “non-profit” Haven Health which is funded by J.P. Morgan, Berkshire Hathaway, and Amazon. Troy Brennan is the CMO of CVS, and CVS owns Aetna.

The Bloomberg article, written by John Tozzi, is entitled “America’s Largest Health Insurer Is Giving Apartments to Homeless People: A radical fix for the U.S. health-care crisis.” Tozzi begins the article by reminding us that since 1986, when EMTALA was passed, all hospitals receiving federal aid have been required to provide emergency care to anyone who needs it whether they have health coverage or not. In reality we’ve had a law against people being allowed to “die in the street” since 1986. Anyone brought to almost any hospital EW in the country will get acute care. That sounds great, but it’s actually a disaster. It would have been much better to pass effective universal coverage that gives everyone access to the medical care they need in the most efficient environment. When uninsured or poorly covered people who need outpatient management, but don’t have financial resources to get the care they need, use emergency rooms for all of their care because emergency rooms are the only place they have any access to care, there is a disastrous cascade of waste and suboptimal care. Our failure to cover everyone for the care they need has turned the most expensive place to get care into the only place where any care is provided for our most challenged citizens. Prior to the passage of the ACA, the cost of this recurrent care for the very poor in EWs, and the hospitalizations that followed, was essentially “bad debt.” Hospitals responded to their losses by asking for more money from commercial payers, which meant that the cost of care went up for employers and for patients who were covered by their employers, as their portion of coverage costs also rose.

After the ACA was passed, many previously uninsured patients became covered for care in the states that accepted the Medicaid expansion. Unfortunately many of those patients have continued to use emergency rooms for their care and have not been effectively integrated into medical practices. In a December 2019 article, the Kaiser Foundation reported that in forty states Medicaid patients are now covered by capitated Medicaid managed care contracts with commercial insurers like United. United has about 11% of that market. I have long felt that when providers were capitated, another way of saying that they are at risk for the cost of care, they will be compelled to pay attention to the social determinants of health. The entirety of my tenure as a CEO was conducted with the principal concept that my primary business responsibility was to prepare the organization to accept contracts with greater performance risk. Triple Aim strategies, including Lean management, were best aligned with our ethical responsibilities and the direction in which I believed healthcare finance had to evolve. Those ideas and the actions they drove like becoming a “Pioneer ACO” often met with the resistance of those who preferred to imagine fee for service reimbursement would be continuing indefinitely.

In healthcare innovation we often see “a pilot.” If the pilot succeeds, the next step is to “scale up” what has been developed to address the needs of a larger population. Population health statistics have shown us that a very small segment of the population uses a majority of the resources. That’s what the statistics showed that Dr. Brenner was generating back in Camden, and that was the message that Atul Gawande presented when he profiled Dr. Brenner back in 2011. Brenner’s data showed where the “hot spots” of utilization were and which populations were getting care in the most inefficient environments. Care that is driven to the EW is not only expensive, it is ineffective because it often occurs long after an initial intervention should have occurred.

When patients are forced to get most of their care in an emergency room their care often violates all six of the domains of quality. Having to wait for hours in an emergency room waiting room or lying behind a curtain on a gurney in a bay of a hectic emergency room waiting to be seen by an intern is not “patient centric” care. Emergency rooms are not necessarily “safe.” The EW is often an environment of hectic activity where unexpected events can generate sudden risks that are hard to control. There is no data set that I am aware of that suggests getting care in an emergency environment is efficient. An emergency room is probably one of the least efficient environments for the delivery of care that is not an emergency. Follow up is often compromised so that the effectiveness of what was done for the patient is often lost through a lack of follow up care, which means that recurrent visits are the norm since no problem was really solved. The care is not timely. Often the “emergency” is the acute recognition of a chronic problem, and the optimal moment of intervention has passed either days, weeks, or even years ago when access to routine care might have prevented the emergency. Finally, the care is not equitable. Years ago I spent up to thirty hours a week working in an emergency room that served a mixed population where I saw many patients that had no access to other care. I would try to get them to return for follow up since there was no other place where they could be seen. The very poor are the people who are willing to wait for hours in the waiting room of an EW. They have no other option. They either have no coverage, or if they have Medicaid coverage, they often can’t find a provider who has an appointment opening that will accept their coverage .

The article does a good job of setting up why the homeless population that United has accepted into its managed Medicaid population is a source of huge potential financial losses. United has the resources to absorb a lot of loss, but they also had the wisdom to hire Dr.Brenner to see if those losses could be addressed by addressing homelessness as one of the most important “social determinants” of poor health. I love some of the lines in this article. Tozzi writes:

…As a society, we’ve effectively decided that people shouldn’t die on the street, but it’s acceptable for them to live there. There are more than half a million homeless in the U.S., about a third of them unsheltered—that is, living on streets, under bridges, or in abandoned properties. When they need medical care or simply a bed and a meal, many go to the emergency room. That’s where America has drawn the line: We’ll pay for a hospital bed but not for a home, even when the home would be cheaper.

It may be true that we do need corporations who understand business strategies to rescue us from such nonsensical behavior. United has spent over 20 million dollars to buy a low rent apartment complex in Phoenix where Brenner is doing his work. They have a business partner that is managing the property. The article has pictures of the complex. There is also an imbedded audio version of the article which you may enjoy. Most of the units are rented as affordable housing, but at least sixty of the units are reserved for homeless people who are covered for their Medicaid access to care through a contract between United Healthcare and the state of Arizona. It is Brenner’s job to identify the sickest homeless patients who are frequently seen in local emergency rooms, and move them into these units.

More than a roof over their heads is provided. They get a “medical home” approach to care for their chronic diseases. They have health coaches, mental health services, access to the medicines they need, and the opportunity to live with some dignity. Tocci offers some examples that Brenner has given to him:

…Steve, a 54-year-old with multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, heart disease, and diabetes. He was homeless before UnitedHealth got him into an apartment. In the 12 months prior to moving in, Steve went to the ER 81 times, spent 17 days hospitalized, and had medical costs, on average, of $12,945 per month. In the nine months since he got a roof over his head and health coaching from Brenner’s team, Steve’s average monthly medical expenses have dropped more than 80%, to $2,073.

That sounds like it will be a win/win for United and for Steve even if we add in what it costs United to provide housing and pay for the supporting outpatient staff which is about $1200 to $1800 a month. United is already planning “the scale up.”

…After testing the idea in Phoenix, Milwaukee, and Las Vegas, UnitedHealth is expanding Brenner’s housing program, called MyConnections, to 30 markets by early 2020. It’s a business imperative. In January, after the company announced a $12 billion profit for 2018, Wall Street analysts pressed Chief Executive Officer Dave Wichmann on the performance of its Medicaid business. The return, he acknowledged, was “not at our target margin range of 3% to 5%.” Wichmann said it would hit the target next year.

There is much more in the article for those who may be interested. Even with the resources that United has, it is impossible for United to provide housing for every homeless Medicaid patient that they cover. Just who is chosen? This is where we begin to see the limits of trying to solve social problems with for profit providers.

One of Brenner’s greatest challenges is deciding who should benefit from the program. Giving patients housing sounds beguilingly simple, but the economics are a high-wire act. Medicaid isn’t paying UnitedHealth anything directly for housing assistance. The company spends from $1,200 to $1,800 a month to house and support each member, so it must save at least that much to break even on Brenner’s program.

On average about 60 members are enrolled in the Phoenix sites at any given time. Once a week, Brenner and his team get on the phone to evaluate potential candidates—anywhere from 2 to 14 people whose names have surfaced in UnitedHealth’s data. They want patients who are homeless and whose medical spending exceeds $50,000 annually, with most of that coming from ER visits and inpatient stays. People living on the streets with less extreme medical costs may need a home just as much, but it doesn’t pay for UnitedHealth to give them one.

For patients above the $50,000 threshold, the reductions in medical costs should let the company at least break even on its investment in housing and services. But it’s not as simple as running the numbers. Brenner is looking for people who not only need help but are ready to accept it. “We want a storyline around, Why is the housing going to make a difference? What’s going on in there? And then what’s the exit strategy?”

I applaud Dr. Brenner’s efforts. I hope that other health systems will address the social determinants of health as a logical strategy to live within the capitated budgets that will surely come their way. We know that capitation did flatten the upward climb of healthcare costs in the nineties, but many felt that those savings were achieved by denying care. Denying care is unethical, and won’t work now. In the interim we have defined the components of quality care. We now know that denying care just moves when care will occur as in an office to a time when the care is delivered at greater difficulty and expense, and the whhen outcomes and patient satisfaction are likely worse.

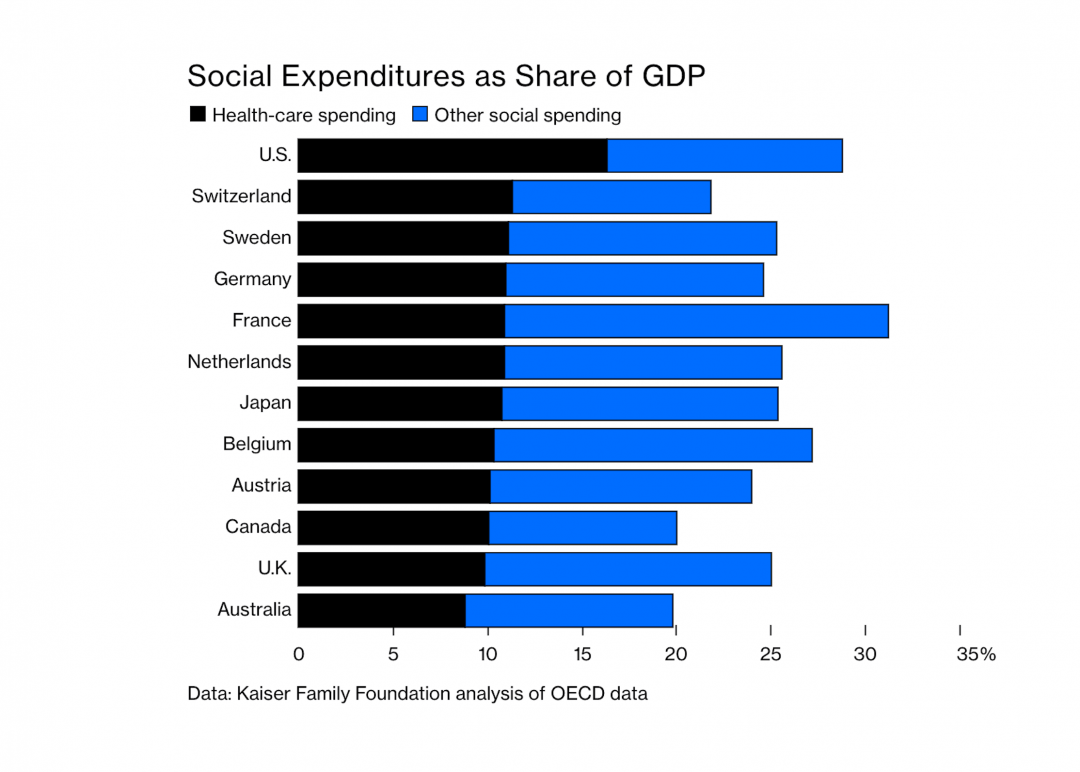

One important part of the paper that I have not addressed so far is demonstrated in a graph that the author copied from a Kaiser Foundation presentation that shows that we spend as much or more of our GDP on healthcare plus social services as other advanced nations spend. We know that with our current mix of social spending and healthcare expenses we are paying more and getting less. It is interesting to ask what would happen to our total expense for both if we spent more on social services like housing. Would that strategy lower our medical expense? Would it improve outcomes? Would we make more efficient progress toward the Triple Aim? You could use Dr.. Brenner’s work with United to argue that such a strategy might be better. Perhaps a different administration might elect to stop trying to cut public funding of social services. A more compassionate approach to the totality of our citizens’ needs might lead to an improvement in well being for everyone, and also be a way to more efficiently use our tax dollars. It would be a delight to see our need for medical spending fall and our quality of life for every citizen improve to levels that other more “socially aware” advanced societies experience.

Johnny Most, the legendary “voice of the Boston Celtics,” had the habit of saying “fiddle and diddle” when the pace of the game would slow down as the next offensive play was being set up. I guess that as we wait for the answers that will flow from the 2020 election many healthcare organizations are “fiddling and diddling.” I don’t think that is what Dr. Brenner and United are doing. Maybe they know something that the rest of us don’t, or they have decided that addressing the social determinants of health is just the best way to protect their profitability. I am even open to the possibility that they believe it is the ethical thing for them to do. Whatever their motivation is, I am delighted that they are leading the way by venturing into addressing the housing issues of the homeless to the benefit of the care of even a small segment of the total population. I hope that there are other insurers that are trying out their own innovations, or perhaps health systems that accept risk and are trying to see what they might accomplish by adopting Dr. Brenner’s ideas and methods.