Sometime after midnight on July 28, I closed my computer. After finishing my weekly letter, I had been watching C-Span 2 on the computer while watching Stephen Colbert do his nightly dissection of the Trump administration on my television. As I turned out the light, I was just hoping that the Senate would go home and go to sleep before exposing us all to the uncertainty of Mitch McConnell’s “skinny repeal.” The majority leader’s strategy was to pass anything so that then the Republicans could hash out something “better” in a House/Senate Conference. There was a risk in that “Hail Mary” approach to delivering on the seven year standing promise of Republicans to “repeal and replace” the ACA with something better. In the worse case scenario House Republicans would have the option of passing the Senate’s bill as it was written and then go home as the president signed away the coverage of at least 15 million people.

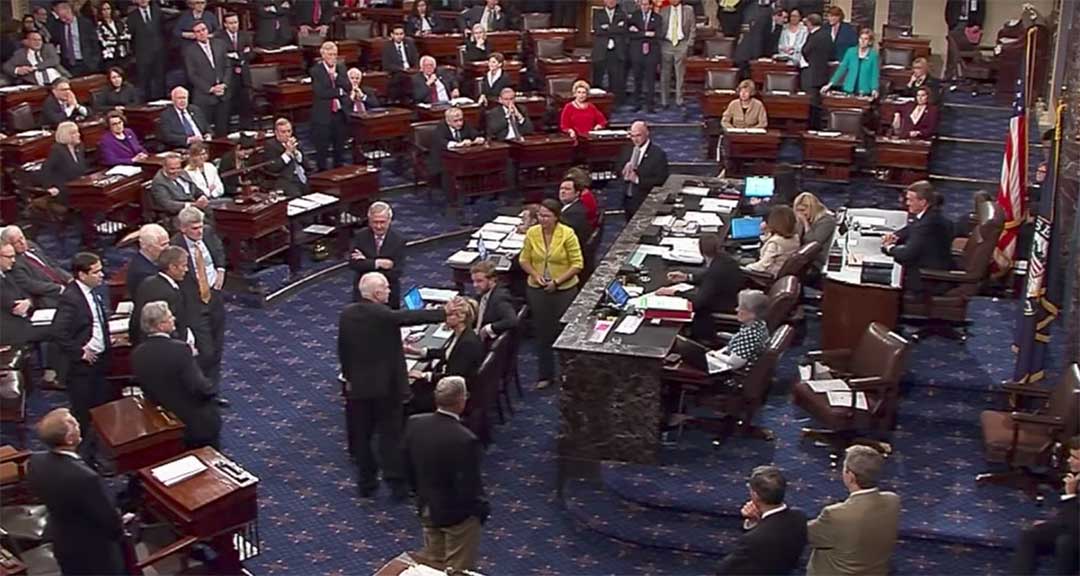

What I could not see on C-span 2 were the conversations back and forth between Paul Ryan and other House leaders, with nervous Senators who wanted assurance that the bill the Senate was about to pass would not be passed by the House, and that the conference between the House and Senate would indeed have a chance to do what Republicans could not do in seven years. We were not able to see the tremendous pressures put on Lisa Murkowski by the Trump administration who had the Secretary of the Interior threaten her with retaliation by cancelling many important projects underway in Alaska if she voted no. She is reported to have been livid. About an hour after I had gone to bed expecting that the bravery of Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski would be for naught, John McCain resolutely walked to the front of the Senate chamber and raised his right arm to signal that he wanted to cast his vote. Then without a word he abruptly turned the thumb on his outstretched right hand down and then walked to his seat as some in the chamber gasped and others gave a muted expression of their positive surprise.

Senator McCain released a statement that explained his vote.

“We must now return to the correct way of legislating and send the bill back to committee, hold hearings, receive input from both sides of aisle, heed the recommendations of nation’s governors, and produce a bill that finally delivers affordable health care for the American people. We must do the hard work our citizens expect of us and deserve.”

Time will tell whether the Senate will return to the “correct way of legislating” and begin a bipartisan process that produces “affordable healthcare for the American people.” But we can trust that we are closer to that objective than we were before Senators Collins, Murkowski, and McCain had the courage to deny the will of their party’s leadership. With their acts of defiance based in their concern and compassion for the millions whose care depends on legislation that moves us forward and not backward, they have given us the hope of a bipartisan process. There are many “next questions.” An important exercise is to try to understand the barriers to a bipartisan process.

Recently, I was excited to hear that Senator Al Franken was going to be the guest on Tom Ashbrook’s daily program on NPR, “On Point.” Franken was there to talk about his new book, Al Franken: Giant of the Senate. Some folks are beginning to ask themselves if a reality show star is qualified to be president, why not a really intelligent former cast member of “Saturday Night Live?”

Early in the program the conversation turned to healthcare. Franken started talking about a public option for counties that no longer had insurance companies that would offer them products on the exchanges. He made comments about the importance of Congress guaranteeing to insurers that the CSR (cost sharing reductions) would continue. That is needed because forgetting the CSR and not enforcing the mandate are great ways for the president to effect his prediction that the ACA is in a “death spiral.” Franken said good things about Senator Lamar Alexander and said that he was willing to work with Republicans in a bipartisan way to repair and strengthen the ACA. He was certain that if Republicans would work with them, he and many other Democrats were willing to go work to in a bipartisan way to repair the ACA.

Franken offered a hopeful resistance to Ashbrook’s recurrent contention that things are a mess. You can hear the show for yourself if you click on the link above. After the opening comments they went to the phones.

The first caller was a woman named Darla from Florida who appreciated what she and others had gained from the ACA, but she was frustrated by her inability to contact her senator, Marco Rubio. Franken tried to offer suggestions that she could try and Ashbrook focused on how ineffective and patronizing his suggestions sounded for citizens who were estranged from the process.

Then came Nancy, a self described middle class independent conservative from Kentucky. She complained that Obamacare was sucking the life out of her. She bought healthcare on the exchange because she was forced to do so, but did not use it. She launched a diatribe against Congress and those not trying to work with the president. She characterized Medicare recipients as freeloaders “sitting at home on the dole” who did not deserve what the ACA gave them.

Franken went into an explanatory mode trying to give each of Nancy’s many concerns a respectful answer, but not accepting her generalization of Medicaid recipients as people who were unfairly pulling her down and costing her money. He pointed out that many of the recipients were disabled, many were the working poor, and others were children or the frail elderly. He talked about his own visits to the poor rural communities of Minnesota where without the current medicaid supports the healthcare system was likely to collapse.

Franken’s answer referenced Atul Gawande’s recent article about the ACA in the New England Journal of Medicine. Franken’s reference to Gawande in his response to Nancy launched Ashbrook on a more vigorous attack of Franken. Franken got little credit from Ashbrook when he accepted that Democrats were to blame in part for the problems with the ACA for failing to educating voters like Nancy. Ashbrook passionately dressed Franken down for ineffectively “lecturing” Nancy in a way that did not recognized her anger and had little likelihood of changing her mind.

Under fire from Ashbrook’s generalized frustration with the ineptitude of Democrats, Franken maintained his humility, his civility and his reliance on facts. Ashbrook contended that Franken’s answer was emblematic of why the Democrats had lost the House, the Senate, and the presidency. Democrats, per Ashbrook, seem to be essentially “tone deaf” to the feeling of the typical Trump voter, the disaffected white blue collar voters of middle America.

Whether real or contrived, the friendly disagreement between Franken and Ashbrook got me thinking about how much of the explanation of this moment in our history is an extension of “us/them-ing.” I was set up to have those thoughts because I had recently read Robert Sapolsky’s chapter on “Us Versus Them” in his book, Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst. Sapolsky’s discussion of “us/theming” cast doubt in my mind on whether we could ever have enough social solidarity to support an effective bipartisan search for our answers to our healthcare challenges like improving the ACA.

“Us versus them” is our species at its best and its worst. Sapolsky reveals that the neurophysiology of categorizing others is a process that occurs in a few milliseconds. Nancy’s collective characterization of the homogeneity of Medicaid recipients is right out of the basic playbook of “us/them-ing” behavior. The technical term for see the “out group” as composed of people who have a “cookie cutter” similarity is called essentialism. I am just as guilty of the “lumping” of thems when I think about people, especially politicians, who do not see the benefits of the ACA.

“Us versus them” is at the core of our most negative politics just as the unity of “us” has given us the ability to work together to defend our way of life, and to work with allies as we did in World War II against threats from authoritarian foreign enemies who were willing to push us versus them to the level of genocide. As I listened to Nancy, I realized that what she imagined to be true about recipients of Medicaid was not thematically much different than Hillary Clinton’s comments about half of Trump’s supporters being in what you might call a “basket of deplorables,” or Donald Trump’s favorite campaign exercise of “theming” Mexican immigrants as rapists and “bad hombres” who needed to be fenced out.

Sapolsky’s discussion of how easy we fall into groups and the reality that each of us is in many groups is beyond the limits of this discussion, but realizing that when I discover that someone lived in the South I know that I immediately feel a sense of affiliation. I saw a guy in South Africa wearing a Red Sox hat, and realized in an instant that we were connected by our affection for the same team. Most of us are constantly dividing the world into two groups, our group and the rest of the world.

Hierarchy and economics further complicate “us/them-ing.” Within your “us” group you see virtue. Within the “thems” you often see evil and ignorance. Them’s or “out groups” are the butts of our jokes. Just as the same “out groups” use humor as a way of tolerating their disadvantaged state.

I have barely scratched the surface of “us/them-ing.” My goal has been to convince you that if we are to ever get beyond the growing sense of division in our society that disables us from solving our healthcare problems we must think creatively about how to manage what divides us. Patty Gabow has correctly diagnosed our most potentially threatening national malady as a “lack of social solidarity.” More and more we fail to see all who live in our country as an “us.” It is even more dramatically true that by not thinking of all humankind as an “us” precludes solving problems as complex as climate change.

Sapolsky not only describes the problem, but he offers some solutions supported by experimental evidence. The answers are complex and a full discussion is again beyond the scope of this discussion and gets into managing biases and the things that create them like priming and framing. A lot of our distress from “us/them-ing” comes from the “thinking fast” automatic responses of Kahneman’s “thinking fast and thinking slow.” At a simpler level more of us need to be self monitoring and self questioning. We need to foster empathy for the “thems.” That means extending ourselves to the “thems.” We must use “inquiry” supported by tolerance until we get to know those who are “them” enough to understand their position even if we have a different point of view.

Thus, in order to lessen the adverse effects of Us-Them-ing, a shopping list would include emphasizing individualism and shared attributes, perspective taking, more benign dichotomies, lessening hierarchical differences, and bringing people together on equal terms with shared goals.

It will take leadership with courage to fan the small flame that may have been sparked by John McCain’s thumb. A guiding biparisan “guiding coalition” might fan that weak flame into a real bipartisan process. We need the sort of Democratic participation that Al Franken and Chuck Schumer say they are willing to provide. Republican “thems” like Rob Portman, Shelley Moore Capito, Lamar Alexander and others need to join the process. It will just take a dozen Republicans and the 48 Democratic senators to write a bill that could be sent to a conference with the House. I believe miracles can occur.