I had planned a quick trip to Birmingham, Alabama last week to take care of a family matter. Originally, I was scheduled to go down on Thursday afternoon and come back early on Saturday morning. Those plans were altered after the airline tragedy that finally resulted in the grounding of all of the Southwest Airline Boeing 737 Max 8 planes. When I was notified that my flight home had been cancelled and the earliest flight back that I could get was late Sunday afternoonI had to deal with the reality that I was going to be in Birmingham for the weekend, I cheerfully embraced the idea as a great opportunity to spend some time with my sister and her husband. She graduated from Georgia Tech, but had started college in Birmingham in the late 60s where she met her husband whose family had been there a long time. They have lived and raised a family in the Birmingham area since their marriage almost fifty years ago.

Mid March in Birmingham is gorgeous. There were clear skies with the temps in the high sixties, and all of the flowering trees were in full bloom. Spring was “busting out all over.” I have been to Birmingham several times before, but not to spend much time to looking around. Alabama has always been an enigma for me. I have taken a dim view of its history of racism and institutionalized white supremacy and resistance to integration as demonstrated by public officials like the infamous “Bull” Connor, the “Commissioner for Public Safety,” who ordered the use of high pressure fire hoses and attack dogs to attack children and teenagers who were marching peacefully to draw attention to their oppression in “Bombingham”, then the most racially divided city in America.

My sister decided that I should see the transformation of the real Birmingham since most of my experience was in Mountain Brook and Vestavia, the suburbs “over the mountain” where she has always lived. Saying that you have been to Birmingham when you have just been to Vestavia and Mountain Brook is like saying that you have seen Boston after visiting Newton and Wellesley. We decided that we would go “downtown” to see the massive medical complex associated with the University of Alabama Medical School where she and her husband get their care, and visit the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, which sits across the street from the 16th Baptist Church which was bombed killing four little girl on a Sunday morning in September 1963. Directly in front of the Institute and “catty cornered” from the 16th Street Baptist Church is the Kelly Ingram Park where civil rights protesters would gather for their marches. Standing in front of the Institute and looking across at the park or looking to my left at the church across the street gave me the same feeling that I have when I visit hallowed land like the Gettysburg battlefield or the Alamo. Going into the Institute, which is really a museum, gave me the same sense that I felt when I entered the Holocaust Museum in Washington. The Civil Rights Institute opened in 1992. The United States Memorial Holocaust Museum opened in 1993.

When I visited the Holocaust Museum in Washington a few years ago, the question being asked was not how the Nazis carried out the Holocaust, but rather what were the other German citizens doing and thinking that allowed it to happen. As a man who was born and raised in the Jim Crow south, I often ask the same question about myself, my friends, and my family. We were there. Why did we accept as normal a divided society that was experienced by a significant portion of the population as a humiliating and difficult environment as a second class citizen at its best, and as victims of constant apprehension and humiliation in a terrorist state associated with lynchings and bombings at its worst? Perhaps, I am moved in a more dramatic way than a visitor who has had no personal experience with restrooms labeled Men, Women or Colored or water fountains labeled White or Colored. I remember friends and family who would call Martin Luther King, Jr. a trouble maker. I witnessed the integration of the University of South Carolina in the fall of 1963.

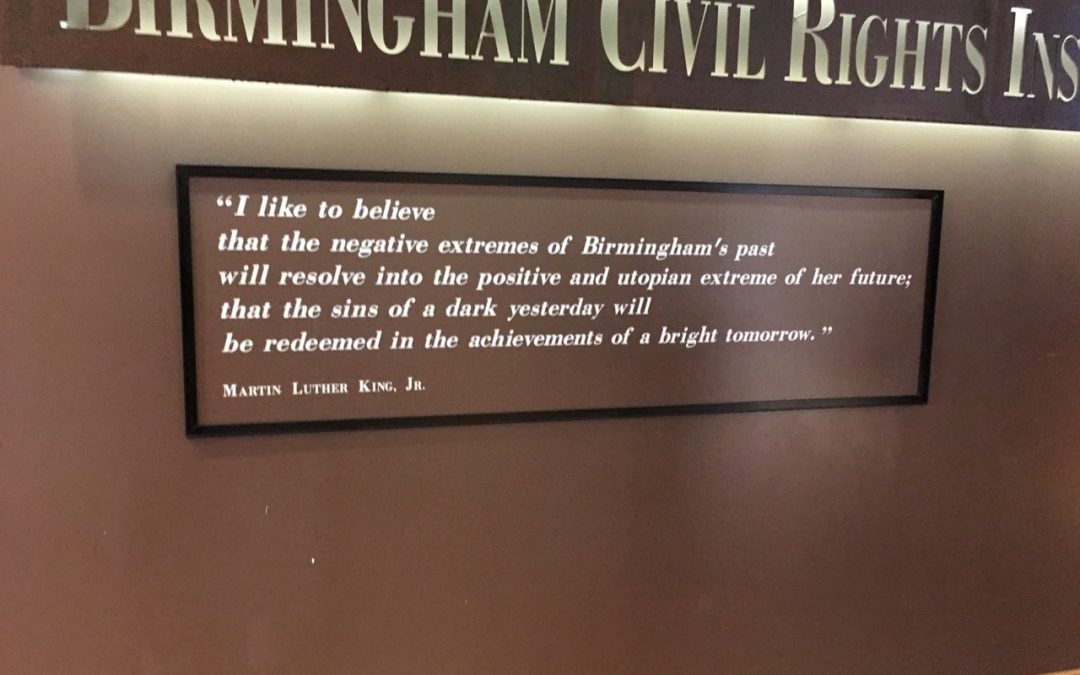

I resonated Dr. King’s words that are carved into the wall of the hall and greet me as I entered. I would like to believe that now, over fifty years since his assassination, they may finally be coming true.

I like to believe that the negative extremes of Birmingham’s past will resolve into the positive and utopian extreme of her future; that the sins of a dark yesterday will be redeemed in the achievements of a bright tomorrow.

The most moving exhibit for me in the museum was the recreation of the jail cell where Dr. King wrote his famous “Letter From the Birmingham Jail.” The 6,000 word letter was written in response to a public letter, “A Call For Unity,” written in early 1963 by eight Birmingham area ministers who suggested that Dr. King and others should discontinue their demonstrations and pursue attempts at desegregation through the courts. The ministers maintained that change takes time, and that the protesters should be “patient.” They implied that the program of resistance that Dr. King and local black ministers advocated and were leading was inconsistent with Christian thought and practice. King’s letter was an answer to their letter.

If you have never read the “Letter From the Birmingham Jail,” I would suggest that you stop reading this letter and click on the link above and read Dr. King’s letter which is a manifesto justifying civil disobedience and is a castigation of the ministers for their failures as religious leaders who look away from the suffering and inhumanity around them. What is remarkable to me are the biblical and historical references that King uses. He wrote the letter by hand from his cell without the benefit of references. If you don’t have time to read, click here and watch a five minute video.

There are a few passages that I want you to read if you can’t read the whole letter or watch the video. As you read what follows, keep in mind what Dr. King is reported to have said about inequities in health care in a speech in 1966.

“Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane.”

There has been some debate about whether those were his exact words. Did he say health or health care? I think it is clear that he was talking about people of all races who suffer because they are denied care. One historian suggests that the full quote about inequality and health is:

“We are concerned about the constant use of federal funds to support this most notorious expression of segregation. Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and the most inhuman because it often results in physical death.

“I see no alternative to direct action and creative nonviolence to raise the conscience of the nation.”

That historian’s conclusion is worth noting, and demonstrates why Dr. King’s passion for human rights for all people is so central to our continuing attempts to improve the health and the healthcare of all people.

The ubiquity of King’s words today (in whatever form) reflects not only their rhetorical power, but also King’s abiding moral authority. The 21st century legacy of King’s gift of these words is that we have a social responsibility to “raise the conscience of the nation” so as to end this shocking and inhuman injustice.

With that in mind consider the following quotes from the “Letter From the Birmingham Jail.”

Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half-truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, we must see the need of having nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that will help men to rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood. So, the purpose of direct action is to create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation. …My friends, I must say to you that we have not made a single gain in civil rights without determined legal and nonviolent pressure. History is the long and tragic story of the fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily. Individuals may see the moral light and voluntarily give up their unjust posture; but, as Reinhold Niebuhr has reminded us, groups are more immoral than individuals….

I think that it is also true that the same tensions King noted exist in healthcare today. Those of us who have coverage and good health may be threatened with the loss of what we have by efforts to extend care universally. Collectively our concerns create an even greater barrier to the goals of the Triple Aim. We are moving slowly and content to make a little progress whenever progressive voices gain some political advantage. In the interim many suffer as they wait. As King says in the letter:

For years now I have heard the word “wait.” It rings in the ear of every Negro with a piercing familiarity. This “wait” has almost always meant “never.” …But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate-filled policemen curse, kick, brutalize, and even kill your black brothers and sisters with impunity; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society; …when you take a cross-country drive and find it necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your automobile because no motel will accept you; when you are humiliated day in and day out by nagging signs reading “white” and “colored”; when your first name becomes “nigger” and your middle name becomes “boy” (however old you are) and your last name becomes “John,” and when your wife and mother are never given the respected title “Mrs.”; when you are harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tiptoe stance, never knowing what to expect next, and plagued with inner fears and outer resentments; when you are forever fighting a degenerating sense of “nobodyness” — then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait.

Perhaps you saw “The Green Book,” this year’s winner of the Oscar for the “best picture.” The movie has been criticized by some, but I found great authenticity in Mahershala Ali’s Oscar winning portrayal of Don Shirley, a gifted black musician trying to travel through the South while enduring all of the indignities and cruelties described by Dr. King in the letter. It is no surprise that the climax of the story, when Shirley says no to performing in a place where he is not allowed to eat, occurs in Birmingham.

Birmingham has made great progress over the last fifty years just as we have made progress toward universal coverage with Medicare, Medicaid, and the Affordable Care Act. A black mayor was elected in 1979, and the airport is named for the most courageous local black minister whose home was bombed. What lies ahead in the struggle for Dr. King’s larger view of human rights which includes health and healthcare for every American depends on a majority accepting the principles that Dr. King espoused in his letter. I hope that someday you might get find yourself in Birmingham with some time to be inspired to do as much as you can to forward the Triple Aim by a visit to the Civil Rights Institute.