I have often written about the importance of the book Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. You may never have read the book or even have a copy on a shelf somewhere in your office or home where it is collecting dust, but you should click on the link for an excellent summary of this landmark publication that was offered by the Institute of Medicine in 2001. The first paragraph remains as true today as it was when it was published seventeen years ago. It is amazing to realize that many children who were born while the work was being produced, and the ideas it contains were being debated, are now in college or will be soon. It has been a long time, and the problems that were identified as issues in the late nineties remain largely unresolved today.

The U.S. health care delivery system does not provide consistent, high quality medical care to all people. Americans should be able to count on receiving care that meets their needs and is based on the best scientific knowledge–yet there is strong evidence that this frequently is not the case. Health care harms patients too frequently and routinely fails to deliver its potential benefits. Indeed, between the health care that we now have and the health care that we could have lies not just a gap, but a chasm.

Don Berwick was one of the contributors to the 2001 book. In an online JAMA article from August 31, 2018 entitled “Crossing the Global Health Care Quality Chasm; A Key Component of Universal Health Coverage” Dr. Berwick was joined by Megan Snair, MPH; and Sania Nishtar, PhD, FRCP in a paper discussing the importance of supporting the global evolution of quality care. Their objective was to expand the concepts of Crossing the Quality Chasm to include the concerns of all people everywhere. They write:

Despite years of investment and research, the quality of health care in every country is much worse than it should be. Problems range from disrespect of people when they are interacting with the health care system, to preventable mistakes and harm, to high rates of incorrect and ineffective treatment.

Early in their article they offer us a new term, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). It occurred to me as I read their work that our country is not a homogenous whole. We have data that demonstrates that there are great differences to access to care and in the quality of care from state to state, and within individual states. Care in Western Massachusetts is much different in real ways from care in Eastern Massachusetts where there are three medical schools and multiple teaching hospitals. The quality chasm in the coal country of Kentucky is surely wider than in the more populated areas of Louisville and Lexington. The quality of all care and the width and depth of the chasm must be different in rural Mississippi than it is in the Bay Area of California. It occurred to me that there could be some benefit in considering the areas in America where the quality chasm is wider and deeper with the same considerations that Berwick, et.al. offer for LMICs.

A major point that they make in their article is a little depressing. They contend that just expanding care and not focusing on the need to simultaneously improve quality and safety could expose people to care that is dangerous to their health! Could that same warning apply to the parts of America where the chasm remains almost as deep and wide as it is in LMICs?

The report states that without correction of defects in health care quality, especially in LMICs, universal health coverage, a key component of WHO’s Sustainable Development Goals,4 will give many people access to care that will not help them and may even be harmful.

We all know the definition or description of quality that was one of the foundational concepts of Crossing the Quality Chasm: The six dimensions of quality are: safety, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity. I have found in previous discussions of Crossing the Quality Chasm that not as many people or organizations are focused on or could site the Ten Descriptors of an Improved Care System:

1) Care based on continuous healing relationships:

2) Customization based on patient’s needs and values.

3) The patient as the source of control. Encourage shared decision-making.

4) Shared knowledge and the free flow of information:

5) Evidence based decision making.

6) Safety as a system property.

7) The need for transparency.

8) Anticipation of need.

9) Continuous decrease in waste.

10) Cooperation among clinicians. [“I to we” within practices, across practices, across systems and throughout the community.]

Perhaps the reason that we have not made more progress in our efforts to cross the chasm everywhere in America is that there are large swaths of our country where it is hard to find a provider organization or health system that comes close to fitting into the template that describes an optimal system of care. In many parts of rural America there are communities that have only one rudimentary care network and access to that system is compromised by the failure of the state to accept the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid. Another reason is that through more than half of the time since the publication of Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century in 2001 as much as 20% of the population had no coverage for care, much like an LMIC, and even now more than 10% lack coverage with the likelihood that the policies of the Trump administration will grow the number.

I have been on a trip recently where these realities stand out. Residents of rural communities in remote places in Oregon and California probably have no more “choice” in their care than similar areas in New Hampshire, Kentucky, Mississippi, or Michigan. In heavily populated and economically active areas of the country it is a different story. My son and his family who live in the Santa Cruz area of California have multiple choices between good systems. They were patients in the Dignity Health System and chose that over Palo Alto Medical Foundation/Sutter Health for reasons of cost and convenience. Now they get their care in the recently opened Kaiser Health Center in Scotts Valley that is pictured in the header for this post.

Perhaps there is no other organization that crosses the quality chasm for more patients, families and communities than Kaiser. It covers more people in more places with lower cost and higher quality than any other system of care. As I go down the list of “ten descriptors of an effective system,” I realize that Kaiser would probably score higher than any other multi state system of care in the country if we were to rank all systems along the parameters described in Crossing the Quality Chasm.

Outcomes are built on existing realities. Perhaps as important as the image of what a system of care that delivers quality looks like is the description of the realities upon which such a system is built. Kaiser matches up well against this list. I had the privilege of being asked as a guest to attend two of Kaiser’s Permanente Medical Group biannual organization wide leadership conferences and can attest to the fact that the list below characterizes the subjects covered in those conferences.

- Systems thinking drives the transformation and continual improvement of care delivery.

- Care delivery prioritizes the needs of patients, health care staff, and the larger community.

- Decision making is evidence-based and context-specific.

- Trade-offs in health care reflect societal values and priorities.

- Care is integrated and coordinated across the patient journey.

- Care makes optimal use of technologies to be anticipatory and predictive at all system levels.

- Leadership, policy, culture, and incentives are aligned at all system levels to achieve quality aims and promote integrity, stewardship, and accountability.

- Navigating the care delivery system is transparent and easy.

- Problems are addressed at the source, and patients and health care staff are empowered to solve them.

- Patients and health care staff co-design the transformation of care delivery and engage together in continual improvement.

- The transformation of care delivery is driven by continuous feedback, learning, and improvement.

- The transformation of care delivery is a multidisciplinary process with adequate resources and support.

- The transformation of care delivery is supported by invested leaders.

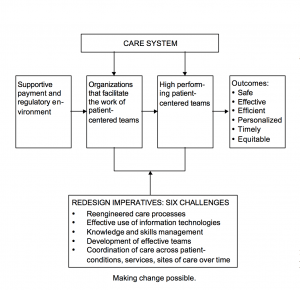

If you clicked on the link to the article about Crossing the Quality Chasm, you would see the diagram pictured below:

I think that Kaiser’s success is mostly a multi decade focus on mission coupled with exceptional leadership and a system of leadership development that is producing tomorrow’s leaders today, but in part is related to the fact that their size and financial structure protects them from the instability in the box “supportive payment and regulatory environment.” The question that I have is why we have not been able to copy Kaiser’s formula for success in every corner of the country.

Berwick and his co authors ask the same question in reference to the underdeveloped countrIes that are the focus of concern in their paper. They see hope in the spread of the Internet. Most of us don’t experience much trouble getting on the Internet via a direct connection or via a wireless access through our cell phones, but there are many rural American communities that still don’t have access. It may be hard to believe until you visit central Oregon or long stretches of the Pacific Coast line in Oregon and Northern California.

Another barrier to quality care in the “LMICs” of the world and in much of America is a shortage of qualified healthcare professionals. If you work in a care system in San Francisco, Chicago or Boston this probably is not an issue for you or the system of care you work in, but I know that general surgeons are an endangered species in many rural locations in Vermont. Try finding a pediatrician in Northern Vermont. A sad reality is that our workforce shortages exist even after years and years of favorable immigration formulas for foreign doctors. It is easy to think of the Internet as “infrastructure” and money can quickly fix the problem. It is harder to put a face on infrastructure and money can’t solve all workforce shortage issues for all the understaffed areas in the country. The final barrier to improvement that Berwick, et. al. review is the political instability and inequality in many of the LMICs. We are plagued with economic inequality that is growing and our increasingly polarized political system is a looming threat.

Just two years ago I had reason to be hopeful that we were finally making progress toward the Triple Aim. Since the election of 2016 we have been fighting valiantly not to lose ground. Not losing ground is an important objective given the current realities, but it is not the same as making progress. Just as several states and cities have pledged to maintain efforts to fight climate change even as the president has taken us out of the Paris Climate Accords, I believe that we will see some states continue to make progress toward the Triple Aim and narrow the quality chasm for their citizens. Some states will fall below where they are now either for political or economic reasons. More and more healthcare policy is likely to be driven by local political processes and if the focus is cutting taxes and limiting “the welfare state” expect continuing loses in the effort even to build a footbridge across the quality chasm. We may find ourselves once again, as we did in Massachusetts in 2006, looking to the states and local governments to supply the supportive payment and regulatory models necessary for care improvement. In the interim, I am very happy to know that we will still have organizations like Kaiser to show us “what good looks like.” “Good” is not “perfect” but Kaiser continues to get better and progress is a proof of concept that that supports hope for the moment.