One of the many lists forecasting what will happen in the New Year predicted that in 2016 many patients will begin consulting a Digital Doctor by using a health app for the first time. The article also predicted a big rise in the use of video visits and video consultations with medical providers. Perhaps to some this sounds like news but my response is, “It’s about time!” The widespread use of computers in medicine has been a long time coming.

The adoption of innovations in healthcare has always been slow, from the moment of possibility to when the innovation is widely appreciated and accepted. The widespread use of penicillin is sometimes presented as a good example. Penicillin was discovered by Alexander Fleming in 1928 after a serendipitous revelation. About fifteen years later, early in World War II, the military recognized penicillin’s benefit in managing infections. It went into large-scale production for military use near the end of the war and then was not generally available until twenty years after Fleming’s discovery.

Atul Gawande speculated about this phenomenon in his 2013 New Yorker article about “slow ideas”. He used the rapid spread of anesthesia in surgery versus the very slow spread of antiseptic surgery to make the point that the difference in rates of adoption had largely to do with physician acceptance and physician acceptance had to do with physician convenience.

“So what were the key differences? First, one combatted a visible and immediate problem (pain); the other combatted an invisible problem (germs) whose effects wouldn’t be manifest until well after the operation. Second, although both made life better for patients, only one made life better for doctors. Anesthesia changed surgery from a brutal, time-pressured assault on a shrieking patient to a quiet, considered procedure. Listerism, by contrast, required the operator to work in a shower of carbolic acid. Even low dilutions burned the surgeons’ hands. You can imagine why Lister’s crusade might have been a tough sell.”–Atul Gawande

I pondered the rate with which we adopt technology while I was listening to Robert Wachter’s excellent presentation earlier this month at the 27th IHI Forum in Orlando. Dr. Wachter is the Professor and Interim Chairman of the Department of Medicine at UCSF. He is also the author of a compelling book, The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype, and Harm at the Dawn of Medicine’s Computer Age. The Boston Globe published a brief review of computers in healthcare on December 28 and in the review featured Dr. Wachter and his book.

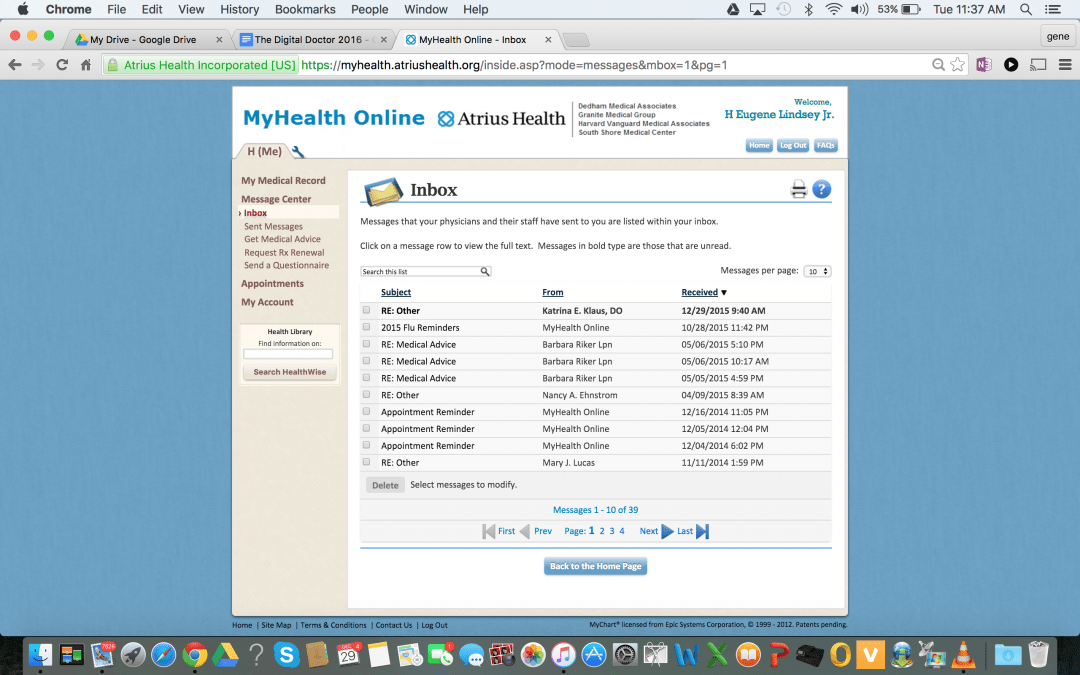

Dr. Wachter began his speech at the IHI by pointing out that because of the 30 billion dollars spent by the government the use of computers in medicine had skyrocketed from 10% of offices and hospitals in 2010 to 75% in 2014. Those of us who have been using computers in healthcare since the late 60s have been joined by a stampede of new users. By nature I am a little shy of being an “early adopter,” but I do get into new technology sooner than many people. I first start using email in the mid-nineties and immediately recognized that putting my email address on my business card in the office would create a closer connection between me and my patients. Harvard Community Health Plan opened its doors in October 1969 with its medical records on a computer. We had been on Epic since 1995 and have had a patient portal for the last decade.

Some patients are early adopters also. The iPhone first came out on June 27,2007, and one of my patients was demonstrating its utility to me within the month. In a little over a year another patient had lost over one hundred pounds using one of its first health apps, “Lose It”.

I had not really appreciated what a rare thing using computers in the office and hospital was for most of the doctors in the country until I heard Dr. Wachter speak. I knew that the use of computers was a point of stress and resistance for many physicians, but I did not realize how successful the resistance had been. One of my objectives as Chairman of the Board and then later as CEO was for our practice to fully leverage the patient portal. I well knew clinicians were worried about how they would be overworked if they were exposed to a tsunami of patient requests from the internet. I also knew it was difficult to get past patients’ concerns about the confidentiality of their records. I just did not realize how far ahead we were of the majority of the rest of the country in digital healthcare.

Computers have always been a part of my practice so it was enlightening to me when Dr. Wachter described just why replacing the paper medical record with a computer has been such a source of stress for most practices. He pointed out that every industry that has become computerized has needed to change the way it works. The old analog workflows do not work well with the new technology. The new technology also creates opportunities for further stress by encouraging disruptors. Think about ATMs and bank tellers, Uber and cab drivers, and the old motel versus AirBNB. He predicts that the pressure to deliver high value care will overlap with the stress of the digitalization of the US healthcare system that will evolve over the next ten years.

He pointed to the transformation in radiology as the canary in the mine. When digitalization of film emerged the x-ray teaching rounds ceased and radiologists making $400K in America were in competition with radiologists making $40K in India. ICUs have had digital technology longer than hospitalists have had digital records. Both now have “alert fatigue”. Residents are no longer writing in charts at the nursing station where other interactions that benefited the patient once occurred, because they are now poring over computers in isolated workrooms. The patient in the bed has been replaced by the iPatient on the screen and we are not quite sure what that means.

Wachter presented the emergence of digital medicine not as “technical” change where the user just had to learn a few new operating principles as the operator quickly mastered the new tool and became more productive, but rather as change that requires the user to adapt:

“…problems that require people themselves to change. In adaptive problems, the people are the problem and the people are the solution. And leadership then is about mobilizing and engaging the people with the problem rather than trying to anesthetize them so that you can just go off and solve it on your own.” —Ronald Heifetz, MD, Kennedy School of Government

He spoke of the “productivity paradox” of Erik Brynjolfsson of the Sloan School. New technology leads to a fall in productivity until the work is reimagined. Dr. Wachter concluded with the expectation that new work flows would emerge. Reimagining work flows so that patients are not left looking at the back of their doctor who is hunched down over a computer in the corner of the office entering data rather than focusing on what matters to the patient is a challenge that he believes we will successfully meet. In our practice Lean has been a huge asset in redesigning workflows but there is still much to be done.

Dr. Wachter is hopeful. He predicted that there would be new and surprising scenarios as we attempt to blend medicine with the new technology. He also predicted that computers would introduce new challenges for human interaction between doctors, patients and families. He told a story about interactions with a family at the passing of a parent where the decision to move to “comfort only” was in conflict with leaving the patient on a monitor. When the family came into the room to sit with their departing loved one they were unable to focus on the moment until the monitor was disconnected. Computers will never relieve us of the responsibility to be aware of where our patients are and what our responsibility is to them and their families.