A small group of people in my community has been meeting recently to examine how we may be more effective in our charitable activities for our community. Our definition of community is not confined to the limits of New London, but is defined more as a region that surrounds Mount Kearsarge. It extends westward toward the Connecticut River and the Vermont border. Northward we look toward Lebanon and Hanover where our major medical resource is the Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center with which our local critical access hospital and its outpatient affiliates are connected. To the east, away from Interstate 89, the population thins and the boundary is nebulous, but the level of poverty increases until you get to I 93 with its ski resorts and access to Lake Winnipesaukee. Southward we bump up against the economy of Concord.

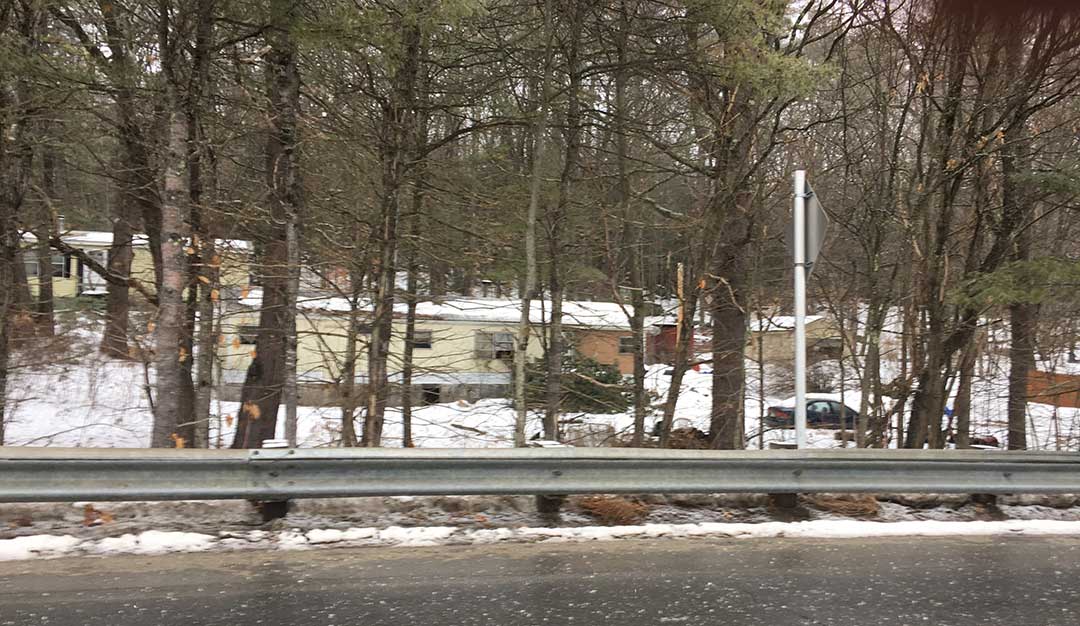

Within this area there are food pantries, non profit social service agencies, and ecumenical groups all intent on alleviating poverty and improving the health and welfare of the community. Each town has a welfare office, there are a few state and federally funded programs, and many of the local businesses try to accommodate the periodic inability of some customers to pay for services and utilities. There is tremendous economic variability in this small region. Homes vary from dilapidated trailers to multimillion dollar mansions on Lake Sunapee. The tax base of the towns vary greatly, but the school system is consolidated for efficiency and for some that supports a sense of a larger community. Despite the full range of economic and educational diversity that exists across the region, there is virtually no racial diversity.

Almost everyone who can work, is working. Many of the poorest members of the community travel long distances to jobs in worn out cars and trucks that are possibly unsafe, but certainly unrelieable as transportation. Many work long hours at multiple minimum wage jobs, and off the record activities. They struggle to balance work and family as exhausted single parents or couples in many different kinds of relationship to care for multiple children. In the freezing temps of the winter, pipes burst, cars break down, and people fall on ice and break bones, as the misery index for the poor shoots through the ceiling.

What I have have learned so far is that good intentions do not assure success. Despite many years of focused effort by well meaning people, pockets of heartbreaking poverty, and human misery exist within a community with deep pockets of wealth. I can only assume that there is also a huge variation in the health of members of this community. Perhaps, compared to many other places some might say, “What’s your problem? Compared to our community you should be happy!” I look at our situation and reason that if we, with all of our resources and efforts, are having problems in an attempt to meaningfully improving the lives of people, we must be doing something wrong. Furthermore, if we, with relatively abundant assets and probably a smaller population ratio of disadvantaged people are having trouble, how in the world are communities without our resources and much larger disadvantaged populations doing it?

As I consider the experience in my community, and reflect on what I learned in the practice of medicine and my years in organizational leadership, I observe that we have a lot of uncoordinated efforts vying for attention and resources. I have come to believe that our inability to make progress in lifting people out of poverty and improve health is not a function of a lack of desire, a lack of knowledge, or a paucity of potential resources. I think other issues are at the root of our failure to make lasting change. To borrow from Atul Gawande, our failure may arise from “ineptitude,” or how we attempt to make a difference.

We are not very good at coordinated activities. We lack a proven methodology, and we have been reluctant to do the sort of critical thinking and process management that we know can yield results. We solve many little problems over and over again, but never establish the connections that could produce effective processes or lead to unified efforts for continuous improvement. It is frustrating to realize that for cultural, political, religious, economic, or some other reason, or combination of reasons, our efforts are very siloed, as is our analysis of the root cause problems we face. In the old debate over “lumping and splitting,” we have come down on the side of “splitting.” My father always advised me that it was impossible to make progress if I mounted my horse and rode off in all directions.

I have been reading and thinking a lot about health equity over the last few years. The longer I look and think, the more I realize the connectedness of the effort to establish health equity to the need to promote all forms of equity. In the recent review of health outcomes versus money spent by other nations of similar wealth, we saw that the healthiest nations directed much of their investment to social issues that we ignore or under fund. I have come to believe that health equity is dependent upon improving racism, improving gender equity, and bringing minorities like the LGBT community into full and equal participation in society. We can’t have “food deserts,” poor housing, and people working for less than a living wage and ever imagine improving the health of the nation in an economically sustainable way. In that context Bryan Stevenson’s statement that the opposite of poverty is not wealth but justice, makes sense. The search for answers should also draw upon the wisdom of Paul Batalden who famously taught us that every system is “perfectly designed to get the results that it produces.”

The IHI is a great respecter of the principles and power of continuous improvement, and has spent decades trying to apply the wisdom of Batalden to the resolution of large problems in healthcare. I was delighted to recently discover that in December the IHI published a white paper, Achieving Health Equity: A Guide for Health Care Organizations, that could be useful to me and my colleagues in our little corner of the world, as well as for you, and healthcare organizations across the country. I fear that many hospitals, large multispecialty practices, and health systems look inward to their own institutional issues more than outward into the communities they serve. We sometimes forget that we are as dependent on our communities as they are on us.

In his introduction to the white paper, Derek Feeley, the CEO of IHI writes:

In 2001, the Institute of Medicine described “Six Aims for Improvement” in its influential report, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century . The “Six Aims” called for health care to be safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable. In the 15 years since the Chasm report, health care has made meaningful progress on five of the six aims (though there is much more work to be done on all). But progress on the sixth — equity — has lagged behind. Forward-thinking organizations have made strides, and pockets of excellence are emerging, but the lack of widespread progress leads some to call equity the “forgotten aim.”

At IHI, we took steps to keep all six aims top of mind — we even printed them on our hallway walls.

Despite this daily reminder, as a leader of IHI, I have to admit to a frustration with our failure to help move the needle on health equity. I know I share this frustration with all of my IHI colleagues, and with so many of you. We hope this IHI White Paper can help lay the foundation for a true path to improving health equity.

Hope, of course, is not the same as a plan. So, this white paper offers practical advice, executable steps, and a conceptual framework that can guide any health care organization in charting its own journey to improved health equity…

I hope that you will download the paper, and add it to your resources as you consider how you can be an advocate for health equity and address all forms of inequity. The concepts in the paper support the idea that racism, poverty, the social determinants of health, housing, employment, education, and the sense of fear that we have from the presence of crime, as well as the heart breaking realities of addiction, are all connected.

I wish it were true that we could make the world a better place with random acts of kindness, and occasional contributions to our favorite charities, but I do not believe it. These good things are beneficial to people in the moment, but insufficient to make a lasting dent in the long term issues that face us. Inequality is a corrosive force. I believe that beyond recognizing it as a source of pain for others, it is really the greatest risk to our collective happiness and the future of the world most of us would choose.

I am not a “Jeremiah,” but I do believe that walls, quotas, prisons, and an attitude of being “tough on crime” has never been, nor will ever be, successful in producing the security and opportunity for joy that we all want. We have the tools. We have the experience. We have had the leadership and may have it again someday. In the interim, and for the long haul, I believe the most effective road forward is to recognize that the Triple Aim, and much that we hold dear depends on expanding opportunity for everyone and pledging to one another a more effective effort to address the unified issues of inequity and injustice that limit our ability to improve the performance of our system of care.