It is paradoxical that despite all of the opportunities for professional satisfaction in healthcare, one of the issues of greatest concern that challenges the Triple Aim is the emotional health and happiness of healthcare professionals. Healthcare is populated by very competent and caring people who chose their profession because of their desire to contribute to better care. Many of those same people are becoming disillusioned, angry and often profoundly depressed.

Most people immediately think of doctors and nurses when they begin to talk about careers in healthcare. I try to have a much wider sense of the expanding opportunities to bring an ever increasing variety of professionals together in the pursuit of the Triple Aim. Healthcare is evolving in new and exciting ways and can be a home for anyone who wants to serve humankind. I believe that most people in healthcare today are there not by accident, but because they want to help people in whatever way their talents and skills might contribute.

No one really knows the numerator or the denominator that fully describes the extent of burnout. All of us have felt the breeze, sensed the change in the weather, occasionally felt the earth tremble or smelled an odor in that air that warns us that something may be on the edge of burning or exploding. Indeed, it is almost amazing that healthcare functions at all given the extent to which its professionals seem to be losing their enthusiasm and compassion as many succumb to the “dark side” of anger and self interest, or worse, become depressed and even are at risk of substance abuse or suicide.

You might ask, “So what’s new? There has been stress in healthcare for a long time.” You may accept that burnout is just a product of our VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous) world. The current realities of anger, depression and burnout that affect so many healthcare professionals have negated or blunted for many the natural sense of great satisfaction from helping patients that I was fortunate enough to enjoy for almost fifty years, from my first day as an orderly to my last day as a CEO. I was hooked by the opportunity for service that satisfied my need for professional purpose. I sense that was true for almost everyone I have ever met in healthcare.

Dr. Paul DeChant’s mission is to help “return joy to practice.” His hypothesis is that part of the solution is to spread Lean culture and methodology. The thought that Lean could hold the answer for the problems that plague healthcare is not new. John Toussaint and Patty Gabow have suggested in their well received books that Lean is a “powerful medicine,” a cure for our “ailing healthcare system.”

Seeing Lean in action in someone else’s practice is not the same as experiencing Lean in your own practice. Reading about Lean tools and process is not the same as actively using the tools in concert with your colleagues to build a Lean culture with the intent of allowing the people who do the work to solve problems and improve processes of care that improve the experience of the patients that trust your organization with their health. It is exciting to observe that the people who are solving problems, eliminating waste, and better serving patients with their new Lean skills in a new Lean influenced culture are not suffering from anger, depression, and burnout.

As Dr. Paul DeChant has observed, most people working in a Lean organization do experience joy in their work. They will tell you that they are excited about the possibility in each new day. They are engaged. What Paul observes makes sense since the frustration, anger, sense of futility and subsequent fatigue and depression were the products of being trapped in a dysfunctional system that they could not fix alone and that negated much of their ability to do the acts of service for people that they came to healthcare to do.

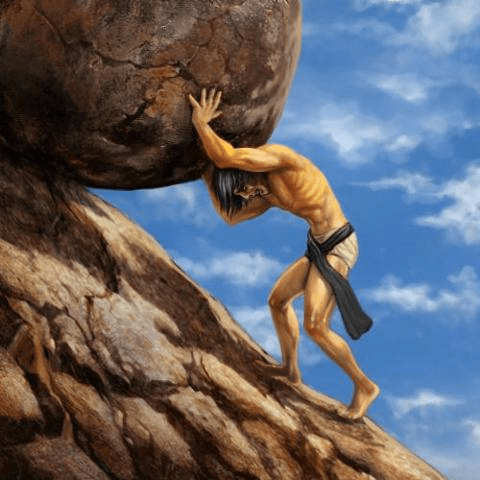

How might Lean turn the anger and darkness to light and hope? My partial answer is that Lean can free healthcare professionals from working in a system that continuously throws them one problem after another to solve again and again, without any permanent sense of solution. Contrast that with what a joy it is to fix something that has burdened you for as long as you can remember! I have seen faces change the minute a person realizes that they might be freed of the frustration of the work that produces their fatigue and frustration. They are no longer living the life of Sisyphus. Now the stone stays at the top of a hill and does not roll back down again!

Another part of my answer requires a reference to Daniel Pink’s fabulous book, Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us (2009). In that important book Pink examines the fallacy that most of us can be managed by the carrot-and-stick approach. Pink asserts that for our work to be meaningful nothing is more important than solving problems. Jobs that motivate us with the joy of solving problems (heuristic work) are much more attractive than jobs where the attempts to motivate us involve those financial incentives and penalties for failure that we call “carrots and sticks.”

Lean recognizes that there is a balance between “standard work,” the safest, least wasteful way of completing a task that we know at this time, and the search for even better “new standard work.” With Lean the people that live under the tyranny of fee-for-service finance are empowered to replace the treadmills of professional misery that cause them to suffer under the demands of more and more volume with their own ideas of how to improve the work. What is more likely to produce joy than replacing those broken processes with new and efficient standard work that they develop by a heuristic process that we call a “kaizen” or “rapid improvement event” (RIE) and through a continuous process of “Management for Daily Improvement”? It is within these processes of improvement that we get the sharpest photo of joy being returned to practice.

Heuristic joy is possible only if people are given the opportunity to solve problems. It is inspiring to see a young medical assistant suddenly produce an idea that is worth testing as an improvement in a process that has been a daily frustration for her and the physicians and nurses that she supports. You can see great joy on the faces of the whole team at a Friday morning “report out” of the new standard work that they have created together over the course of the previous four days.

To capture and multiply the positive effect of solved problems requires structure that provides tools and the ability to transfer and accept what has been learned. When we think about tools we are generally either thinking about machines or the tools that make machines. What is remarkable about our age is that tools are more often composed of ideas and information than steel and rubber. Lean is not delivered on a truck and you cannot buy it from GE or Siemens. The most significant component of the transformation is a new type of leadership that exists as “standard work” throughout the organization.

Jim Collins gave us an advanced understanding of leadership in Good to Great with his picture of the “servant leader” or “level five” leadership. Bob Johansen in Leaders Make the Future: Ten New Leadership Skills for an Uncertain Future described a new set of competencies that many senior leaders will need but do not possess. Lean leadership principles permeate every level of the organization in a fashion somewhat similar to Collins’s description of five levels. Lean leadership also requires new competencies and it goes even further in its requirement of personal transformation of leadership as the essential ingredient in the creation of a Lean organization that has the power to restore the joy of being a healthcare professional. Lean leaders works at every level of the organization by coaching, mentoring and teaching and not commanding and controlling.

John Toussaint’s latest book, Management on the Mend: The Healthcare Executive Guide to System Transformation clearly states the challenge that faces any organization that sees Lean as the answer to the their attempts to survive in the current complexity of healthcare. He writes:

The most common problem I see is that leaders fail to recognize the magnitude of change that will be required and that change extends to leaders on the personal level.

Don Berwick has recently underlined the importance of using “continuous improvement science” if we are to advance toward the goals of the Triple Aim. For my money, Lean remains the most attractive form of improvement science. Lean is where I would recommend the leadership of any healthcare organization should look if it senses that it should be concerned about “burnout.” It is such a painful thing to see people who came to healthcare in response to the “call of service” and are now suffering from problems that have proven solutions.