More often than I like to admit, I am surprised and embarrassed by my lack of familiarity with something that is news to me that has been general knowledge for others for some time. It happened again this week. I had never heard of communitarianism or Amitai Etzioni and the communitarian agenda which he had helped to develop with other like minded academics and philosophers.

I happened on to this political philosophy totally by accident. This last week while visiting my oldest son and his family in Florida for “grandparents day” at my granddaughter’s school I had some free time and decided to look through the family library to see what they were reading, and to see if their shelves contained anything interesting that I might want to read. My son and his wife are both attorneys. My son is a litigator, and his wife is a judge, so I expected to see the usual legal titles. They are both avid readers, as is my granddaughter, so I was also interested in discovering what they were reading when they were not reading about the law.

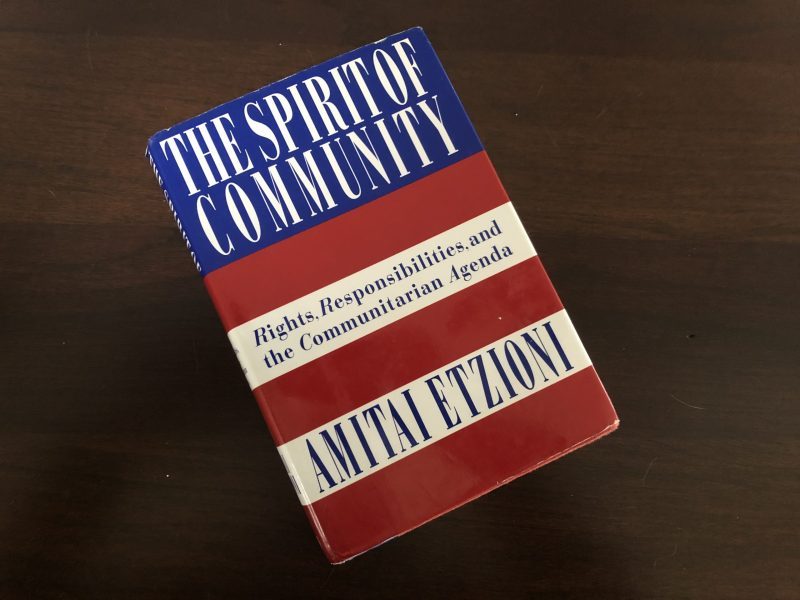

On a high shelf I saw a book with an intriguing title, The Spirit of Community: Rights, Responsibilities, and the Communitarian Agenda. I was surprised by the date of publication, 1993. I was also surprised as I began to read the jacket. It announced:

America needs to move from “me” to “we”…The Spirit of Community calls for a reawakening of our allegiance to the shared values and institutions that sustain us…We have many rights as individuals…but we have responsibilities to our communities, too…We as a nation have in recent years forgotten such basic truths of our democratic social contract. And what we need now is a revival of the idea that small sacrifices by individuals can create large benefits for all of us.

Etzioni wrote a retrospective review of communitarianism in 2014 which describes its evolution culminating in the publication of the book:

The Spirit of Community seems to be the first communitarian book aimed at a non-academic readership. Its main thesis was the next correction ought to be not pulling society in the opposite direction to rampant individualism—but toward a middle ground of balance between individual and communal concerns, between rights and the common good. It was followed by the issuance of a platform. Its drafters and initial endorses included James Fishkin, William A. Galston, Mary Ann Glendon, Philip Selznick, Thomas A. Spragens, Jr and Amitai Etzioni. It was initially endorsed by close to 100 American and other scholars and public intellectuals from a wide political spectrum that struck a similar position, as well as scores of articles in the popular press, radio and TV appearances.

In the 1990s these communitarian ideas received a measure of public support and several public leaders in several Western democracies wove such ideas into their campaigns, including Tony Blair, Bill Clinton, Dutch Prime Minister Jan Peter Balkenende and Barack Obama. These ideas also paralleled or resonated with those embraced by the New Democrats in the US, Germany’s Neue Mitee party and New Labour in the UK, as well as many Scandinavian parties, particularly in Sweden and Denmark. A considerable number of voluntary associations revised their respective bill of rights to become a bill of rights and responsibilities. And—a group of 30 former heads of states attempted to complement the UNUDH with a Universal Declaration of Human Responsibilities.

Why had I not heard about Amitai Etzioni or communitarianism? I later learned that he had been a presidential adviser to Ronald Reagan in the early 80s, and was able to corroborate his claim that his work has had a profound influence on Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Tony Blair. I asked my son about the book. He said that he read it when it was a new book back in 1993 or 1994 while he was getting his LLM in constitutional law at Columbia Law School.

As I read on when I first found the book, and before I did my review of Etzioni on the Internet, I was not sure if I was reading the work of a sectarian liberal or a religious conservative. What were his core beliefs? As I read about his concept of communitarianism, I realized that it was a reaction to the focus on unbridled individualism that is central to liberal political thought and an equal push back from the “pull yourself up by your own bootstraps” philosophy of conservatives. In essence, it is a philosophy that requires balancing conflicting ideas. It is an alternative to the orthodoxy and authoritarian tendencies of both the left and the right. It was the idea behind Bill Clinton’s “third way.”

The introduction to the book begins with a manifesto:

A New Moral, Social Public Order–Without Puritanism or Oppression

We Hold These Truths

We hold that a moral revival in the United States is possible without Puritanism; that is, without busybodies meddling into our personal affairs, without thought police controlling our intellectual life. We can attain a recommitment to moral values without puritanical excesses.

We hold that law and order can be restored without turning this country into a police state, as long as we grant public authorities some carefully crafted and circumscribed new powers.

We hold that the family– without which no society has ever survived, let alone flourished–can be saved without forcing women to stay at home or otherwise violating their rights.

We hold that schools can provide essential moral education–without indoctrinating young people.

We hold that people can again live in communities without turning into vigilantes or becoming hostile to one another.

We hold that our call for increased social responsibilities, a main tenet of this book, is not a call for curbing rights. On the contrary, strong rights presume strong responsibilities.

We hold that he pursuit of self-interest can be balanced by a commitment to the community, without requiring us to lead a life of austerity, altruism, or self-sacrifice. Furthermore, unbridled greed can be replaced by legitimate opportunities and socially constructive expressions of self-interest.

We hold that powerful special-interest groups in the nation’s capital, and many state houses and city halls, can be curbed without limiting the constitutional rights of people to lobby and petition those who govern. The public interest can reign, without denying legitimate interests and the right to lobby of the verious constituencies that make up America.

We hold these truths as Communitarians, as people committed to creating a new moral, social, and public order based on restored communities, without puritanism or oppression.

That introduction left me even more curious about why I had not heard of the movement since it seems to have influenced so many politicians of note, and since the issues it seeks to address have plagued us in increasing intensity over the quarter of a century since it was written. I decided to learn more about Etzioni and the movement.

Etzioni is an interesting figure. He has written forty books, and he is still writing books in his nineties. In 2018 he published LAW AND SOCIETY IN A POPULIST AGE: Balancing Individual Rights and the Common Good and in 2019 he wrote Reclaiming Patriotism.

In the New York Times review of THE SPIRIT OF COMMUNITY: Rights, Responsibilities,and the Communitarian Agenda witten in April of 1993, Edward Schwartz writes:

COMMUNITARIANISM. It sounds more like cult than political philosophy, but “communitarian” is a reasonable description of the ideology that Amitai Etzioni is promoting here. He wants to persuade us that through building a “spirit of community” place by place throughout the country, we can restore an ethic of civic responsibility to society as a whole. As Mr. Etzioni defines it in “The Spirit of Community,” communitarianism cuts through traditional political differences, offering a home to liberals who advocate national service and conservatives who favor tough sanctions against drug use. Indeed, his communitarianism is a tent big enough to shelter anyone who believes that citizenship entails responsibilities as well as rights, presented as an entirely new political ideology to guide the nation in the years ahead.

What I read as I perused the book, and as I researched what others had written about communitarianism, saddened me as I realize that rather than build on the sense of community that Etzioni and others had advocated 27 years ago, we had allowed the rifts that he was seeking to close with a philosophy of commitment to building community to widen to the point that we face a future with the possibility of even more discord and perhaps the emergence of a form of authoritarianism that we had previously associated with countries that did not enjoy the rights and privileges that we took for granted.

Schwartz was not completely sold on the ideas Etzioni was selling in the book, and tried to explain the potential impact of communitarianism to readers in 1993:

“A communitarian perspective does not dictate particular policies,” the platform insists, but public policy is what it seeks to change. To strengthen families, employers need to create new opportunities for parents to work at home. Divorce laws need to be changed to protect children. Schools must provide moral education. Communities must institute drug and alcohol testing to enhance public safety and require people with AIDS to disclose their illness to health authorities. Government must encourage national service, and legislators need to revise campaign finance laws to minimize the influence of money. It is an agenda with something for everyone, to be sure, but one that flows logically from the ethic of political obligation that Mr. Etzioni seeks to foster and preserve.

When Etzioni suggests that we focus too much on “rights” and not enough on “responsibility,” he is stating the same case that President Kennedy stated when he asked us to consider what we could do for our country, and not what our country could do for us. It was interesting for me to try to apply Etzioni’s thinking about rights versus responsibilities to the question of whether healthcare is a right or an issue of individual responsibility, and the ultimate overall benefit to the community of ensuring that everyone has access to the care they need as a foundational strategy for any community. Etzioni implies that anytime we seek to justify our point of view by claiming it as a “right” we immediately end the conversation since the other person in the conversation has no room for negotiation. By claiming a “right,” whether it be the right to bear arms or the right to have healthcare, housing, or a living wage, we deny the point of view of others and suggest that there is no merit in their opposing opinion. We have a win/lose situation that creates anger and hostility. When we approach each of those issues as a chance to collectively improve our communities we may have more success in closing the inequities that are so obvious.

As a solution to the futility of claiming a “right,” Etzioni advocates for a dialog about what is best for the community. It is easy to put forth an analysis of why it is good to have a healthy community. Likewise, if it is clear that according to Etzioni it should have been possible to have a conversation about how to ensure gun owners that they could use guns for acceptable activities, if we had a conversation about how to manage the risk of guns getting into the hands of people who are dangerous to the community. One could argue about whether either conversation was ever possible, but there is no doubt that if these conversations would have been hard in the mid nineties, it feels like they are nearly impossible now.

In the review of communitarianism in Wikipedia we read:

The main thesis of responsive communitarianism is that people face two major sources of normativity: that of the common good and that of autonomy and rights, neither of which in principle should take precedence over the other. This can be contrasted with other political and social philosophies which derive their core assumptions from one overarching principle (such as liberty/autonomy for libertarianism). It further posits that a good society is based on a carefully crafted balance between liberty and social order, between individual rights and personal responsibility, and between pluralistic and socially established values.

Responsive communitarianism stresses the importance of society and its institutions above and beyond that of the state and the market, which are often the focus of other political philosophies. It also emphasizes the key role played by socialization, moral culture, and informal social controls rather than state coercion or market pressures. It provides an alternative to liberal individualism and a major counterpoint to authoritarian communitarianism by stressing that strong rights presume strong responsibilities and that one should not be neglected in the name of the other.

Robert Putnam, the Harvard professor and author of Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community is a communitarian. His observations on our individual isolation may be an explanation for why we have not moved in the direction that Etzioni advised us to go in 1993. I was impressed while reading David Brooks’ recent book, The Second Mountain:The Quest For A Moral Life that what he was writing was in part a lament about the swing of our national community orientation of the 50s to a society of failing and unhappy individuals in current times. Mark Epstein writes in his New York Times review of the book:

Brooks believes in the ground-up remaking of community rather than in top-down government-inspired reform. He faults the culture’s freewheeling encouragement of rampant individualism for most of society’s ills and puts this blame squarely on “free-to-be-you-and-me” liberalism.

The opportunity to return to, or at least accept a revision of communitarianism was recently reviewed by Chayenne Polimedio in an article published last June by New America. She writes in Communitarianism 2.0: What might a new social contract for the United States look like?

Healthcare for all. Free college. Taxing the ultra-millionaires. The 2020 campaign cycle has already witnessed an important paradigm shift in U.S. politics and policy design. So many of the ideas that candidates like Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Cory Booker, and others are espousing on the campaign trail today—ideas that are almost “no-brainers”—were, not too long ago, perceived as impossible. More than that, they were seen as an affront to what many believed to be one of the United States’ most fundamental values: individual liberty.

These days, however, the disavowal of the notion that an individual’s grit, determination, and perseverance are the sole determinants of success is now central to much of the political sparring ahead of the 2020 presidential election. In particular, this challenge to the centrality of personal responsibility has underscored a broader diagnosis: that a system that should distribute power equitably—that is, U.S. democracy—is broken. The bootstrap myth, in other words, leaves out the reality that deep-seated political and economic inequalities create a lopsided playing field.

After that excellent summary of where we are she continues with an updated version of communitarianism for our times:

A new politics, one that stretches beyond 2020, will ask: What do we owe each other?

We Were Never Supposed to Bowl Alone

U.S. democracy is unique in the way that it was designed to be the product of the tension between Lockean liberalism—focused on individual liberties—and ancient Greek democracy—based on the concept of a citizenry that has a share in both ruling and being ruled. Under this model, the Constitution strove to “secure the common good of the society, the happiness of the people, and a complex public good that incorporates such elements as a due sense of national character, the cultivation of the deliberate sense of the community, and even extensive and arduous enterprises for the public benefit.”

That is the way it once was:

But over time, these ideals weakened or were lost altogether. With the Gilded Age of the late-19th century, the idea of the common good gave way to the primacy of “self-made” economic success…

By the 1990s, a movement backed up by scholars including Amitai Etzioni, William Galston, Robert Putnam, and Michael Sandel proposed a new language: one that acknowledged that duties and rights could co-exist. This concept of communitarianism—that is, “a social philosophy that, in contrast to theories that emphasize the centrality of the individual, emphasizes the importance of society in articulating the good”—became the alternative lens through which to see the Founders’ vision for the United States.

Communitarianism combines “progressive thinking with traditional values of community commitment,” and in doing so, it has the potential to “catalyze the conversations necessary for achieving constructive change,”

The way Ms. Polimedio describes the situation, communitarian solutions are highly aligned with issues that we have considered in our discussion of the future of healthcare where the “individual” includes more than individuals who are healthcare providers. The “individual” is often an entity like a health system, a hospital, an insurer, or the supplier of a medical device, data, or drugs. Don Berwick was speaking in this vernacular when he announced the 3rd Era of Medicine, The Moral Era.

Ms. Polimedio continues:

….the crux of U.S. democracy has remained the same: how to realize the idea of the common good in a highly individualistic society…

Today’s record-high levels of social isolation and depression, as well as the increase in negative partisanship, are symptoms of a politics that’s still based on a rights-vs.-duties dichotomy…

Government, too, can be a champion of community and mutual responsibility. The social bonds developed in religious communities, the collective wins engendered by workplace unions, and the spirit of civic duty that permeates voluntarism shouldn’t have to be constrained to the “civic realm.” Policy design that successfully merges the public and private realms of life, and an approach to governance that has a clear moral basis, has the power to create a new social contract for Americans. That, in turn, could transform the way we think about the common good in a highly individualistic society…

Her conclusion is an echo of Etzioni’s position that I found in his 1993 book:

A new politics beyond 2020—one that asks what we owe each other—has the power to prod us to rethink economic, social, and family policy. It can lead to practices in policy design that reflect the upcoming demographic, cultural, and political shifts that the current “individual first” model isn’t equipped to address.

She presents a way to build a bridge across what divides us. We have had these ideas for more than a quarter century. Can we act on them?

…a new, compassionate politics will, as sociologist Amitai Etzioni told me, look at how more universal programs foster a “shared understanding of values and morals.” Because universal programs aren’t “openly distributive, but instead benefit all,” conservatives and progressives alike tend to support them, Etzioni said. Think of social security and medicare, and how the majority of voters are not only in favor of these programs, but also would support their expansion…

Put another way, these are policies that aim to nurture the common good by advancing a vision of democracy rooted in mutual responsibility for one another.

As Barack Obama told us, we should move beyond a red America, or a blue America, and return to being one America, one community. I was inspired and filled with hope when I heard those words in 2008, and hope that now in 2020 we might find a leadership that would return to those themes, and has the ability to convince a majority of us that we can all be better with less focus on “me” and more focus on “we. ” If we can make that shift at this late date, we could ensure the permanent greatness of America. We could become what we have always wanted to be. We could live up to the challenge of the ideals in our founding documents, and we would be able to more effectively address the social determinants of health, the epidemic of gun violence, the opioid crisis, the damage of substance abuse, and the other diseases of despair. The Triple Aim would no longer be an impossible dream. It would be an achievable reality.

Ms. Polimedio sums it up this way:

The pay-off of a bold approach to how we design policy is a politics that can combat isolation and polarization, and equalize power. It’s also a politics that can help individuals—religious and secular—find a higher purpose. There’s nothing un-American or undemocratic about that.

Who knew? I am glad that I found that book, and I am delighted with the journey of discovery that it launched for me. I know it’s just a dream, but it allows me to hope that though it might take a miracle, there is reason to have the “audacious” hope that someday we will join hands in a healthy community that grants us all the individual liberty and health we need to be what we can be.

This may be your best blog yet! Nice job.

Thanks so much, Gene, for bringing Amitai back into my life! On the surface, that sounds ridiculous…but it is simply a commentary on the distortions that have occurred as sociologists try to prove they are scientists. I recall having an interest in Etzioni’s work early in my sociological work (he was, after all, officially a sociologist). The facial sneering was sufficiently intimidating for me to abandon any pursuit of his work. How sad! That said, my interest in how urban housing growth occurs has been a central issue for me–because of the dreadful consequences of housing segregation (economic as well as spatial) we allowed in this country. Sadly, I fear the regentrification of our cities will do little to restore Etzioni’s vision.