“Consolidation, competition, and innovation are the answer to what?”, you might ask. Keeping it simple, I mean the high cost of care and the Triple Aim. To keep it short I could just say, all three will help, but even maximized to the nth degree they will never in and of themselves be enough to lower the cost of care to levels enjoyed by the other equally developed nations of the world. Other countries lower their healthcare costs by leveraging a more effective combination of universal coverage and focused investments in social issues like education, housing, and social services.

My apprehensions about putting too much faith in platitudes and superficial thinking are directed at those politicians and others who offer simple solutions to complex problems and tout innovation and competition as the goals their bills will achieve. I am also taking aim at the healthcare executives who claim that they would be more innovative and competitive if they could just expand their reach by mergers that create larger enterprises. I do believe there is a role for consolidation, competition and innovation. All three are necessary but none alone, or even all three together, is sufficient to lower the cost of care. That said we need to be focused on how we use them and not overly optimistic about what they will accomplish. Doing any of the three effectively is hard work.

As noted last week, there are many barriers to consider when we try to optimize innovation within a single enterprise. I am sure that you can add others to this incomplete list which I have already begun to try to revise.

- Satisfaction with the status quo

- Complex systems where one unit can exist comfortably for a while as others suffer

- Apprehensions of middle and upper management

- Today’s work

- Effort versus immediate benefit

- Matching what can be done with what needs to be done

- Funding in an era of external pressures on finance

- Incorporating potentially effective innovations into work flows

- Aging professionals and emerging workforce shortages

- Red ink and the need to cut the budget

The major emphasis of this discussion is innovation within organizations, but before going further I should insert the idea that innovation between enterprises may offer us as much or more benefit. I will come back to that idea next week when I discuss what I call “consolidation.” The most beneficial “innovations” may lie at the level of public policy or collective action at the local, state, or federal levels.

Under the Obama administration innovation was a high priority that was embodied in the creation of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI). The future of CMMI in the Trump era remains uncertain. Recently CMS announced major changes in the pilots examining bundled payments for orthopedic surgery and cardiac disorders. Gone for a while at least is the sense of possibility that thrilled me when Atrius Health accepted the challenge to be a part of the Pioneer ACO project. ACOs remain a growing potential for innovative cost reduction in an era of potential value based reimbursement that is increasingly embraced by insurers, but do ACOs live under a cloud of uncertainty?

I should clarify what I mean by innovation. I learned from colleagues at Simpler who are expert engineers with a vast understanding of the difference between innovation, invention and improvement that an innovation is a totally new presentation that may combine elements of many inventions and improvements, but most characteristically delights customers. We all immediately think of Steve Jobs and the iPhone.

Jobs was not an inventor. He led a team that brought other people’s technologies and inventions together in a way that delighted customers who never imagined that their phone could be a personal computer, an access to a library containing their favorite music, a health promoter, a way to see people in real time on the other side of the world, a combination movie camera and high resolution camera, a musical instrument, and much much more. Ironically, it seems like most millennials rarely use it as a telephone. They will not answer if you try to call them. Finally, as it has been widely copied by others, it is on a trajectory of increasing utility. More about that when we discuss competition. All that said, I am lumping innovations with improvements and inventions for this discussion even though I know that there will be purists who might object. I am also extending the concept of “innovator” to include the early adopters and mimics of innovators.

To use innovation to improve and lower the cost of care within an organization these barriers and more must be addressed. Even if we remove the intensely expensive process of creating innovations which is far beyond the financial capabilities or expertise of most health systems and practices and opt just to incorporate other people’s innovations, we are still looking at most of the barriers.

When I think of an organization that has distinguished itself as an innovator I usually see a senior leader in my mind’s eye. I see a Glenn Steele, a Rick Gilfillan, a Gary Kaplan, a Patty Gabow or a John Toussaint. Without leadership things may be created or adopted early from the work of others, but successful deployment of the innovation is at risk from the start because of the powerful realities of the external pressure of finance and the internal rigidity of the status quo reinforced by the immediate resistance of the need to do today’s work. With the burden of failing organizational finance and the inefficiencies of the workflows of the status quo, is it a surprise that a frightening number of medical professionals are experiencing burnout and have a blank stare to meet the announcement of yet another “innovation” that they must master?

Innovative organizations have cultures that clarify why they exist. They articulate the expectations between their management and professionals. They have established trust between managers and the people who deliver their services. These organizations usually have effective programs of quality improvement. They have widespread knowledge of, and acceptance of, some process of continuous improvement like Lean. These assets can only be acquired through time and resources invested in staff education and the exercise of “distributed leadership”.They understand the concepts of “relational contracts” and the principles of “subsidiarity” and “federalism.” On such a foundation middle management is empowered and more inclined to seek the opportunity to incorporate innovations into the workflows that they facilitate rather than undermine what’s new motivated by the fear that what is new will cost them control and security.

Healthcare professionals often have years of experience that are challenged by innovation. An innovation, if adopted by your hospital or practice, may turn what you previously envisioned as a glide path to retirement into something that feels like climbing El Capitan. When you are a master of the past and have a financial or personal stake that change may undermine, you may show up to the meeting that discusses a proposed innovation with questions and concerns that are a polite way of saying, “Over my dead body!” Personal success for a while is possible in a failing organization.

Most of us own electronic gadgets and tools that we can’t operate, and are content never to realize the full value of the money we have spent. Why is that? Speaking for myself I can say that what seemed like a good idea when I laid my money down was not discounted by the frustration I would realize when I tried to get my gizmo to connect to the Internet. Ownership is not usership. Innovations yield a return on investment only when used. What percentage of the capabilities of your EMR do you use? What percentage of its “tools for practice management” have you incorporated into your daily work routine? Most clinicians use their EMR in ways that track more similarly to their use of a paper record than the practice management/population management/ financial management tool that it is. Is it a surprise that Meaningful Use was far from a popular pay for performance opportunity? When the effort required today to learn and incorporate an innovation into today’s workflow is balanced against today’s schedule and a steep learning curve that must be climbed at the expense of precious moments of respite, it is little wonder that what Machiavelli told his Prince about innovation 500 years ago is still operative today.

“There is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success, than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things.”

In other industries leaders seem better equipped to make the “pain of not changing [innovating] greater than the pain of change.” The worry of us all should be that resistance to innovation will be successful while our enterprise is still successful and still has the resources to invest in innovation. Innovation is best done when it is “anticipatory” of the opportunities it will enable. Sadly, we often see enterprises that have the ability to resist innovation and delay the pain of change until it is too late for any innovation to allow them to avoid the pain of collapse and failure.

Jim Collins’ classic book Good to Great is a favorite of many of us, but few know about his important sequel, How the Mighty Fall. I have never seen a hospital or practice that got to the place of deep cuts in personnel and services in its last agonizing efforts to stay afloat, or maintain its cherished independence, recover by “innovating” or launching a successful program of continuous improvement in the eleventh hour. Every moment has its opportunities and possibilities as well as plenty of good reasons to put off innovation and improvement until later or when “things are better.” Red ink is not consistent with improvement. The anticipatory recognition that innovation and improvement are ways to avoid darker days requires courageous leadership and supportive governance.

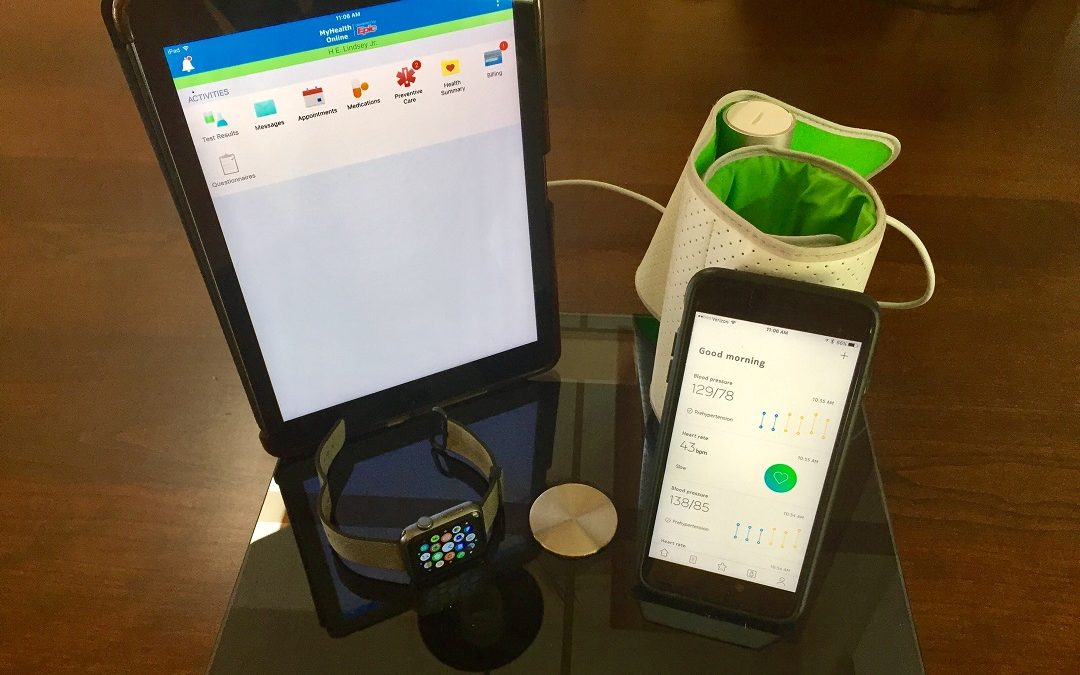

Too often when we talk about or think about innovation we are thinking about a software product, some app, or some new medical device or technological game changer. Those things are great and I am all for them, but I must emphasize that ideas and actions can constitute innovations also. I am very hopeful about the potential to lower the total cost of care through more effective patient engagement, especially in the self management of health and chronic disease. It should be possible to envision a day when a hospital admission for an ambulatory sensitive diagnosis is a “never event.” That is an audacious goal. I do not think that current processes of ambulatory care will ever get us there. Innovations may.

To put it bluntly, for most people getting care from their doctor is a frustrating experience. Time is wasted, patients and their families are inconvenienced because care is delivered in a way to maximize the financial yield. I know that your practice or hospital is not like this. But remember you are a small part of the vast system of care in this country. The ambulatory practice financed by fee for service revenue is usually an impossible environment in which to attempt to promote patient engagement or pass on the tools of self management. All of the drivers point toward a quick visit billed at the highest possible level with the earliest possible return of the patient. The principles and possibilities of the “experience economy” described almost twenty years ago by Pine and Gilmore have not penetrated this reality, despite all the attempts by enlightened organizations to act like the Ritz-Carlton or despite all the Press Ganey surveys.

I have the hope that someday all of our innovations will come together to yield

…Care better than we’ve seen, health better than we’ve ever known, cost we can afford,…for every person, every time,…in settings that support caregiver wellness…

Innovation will be an important part of that future success, but realizing its real potential will require transformational change.