Recently I attended a meeting in suburban Washington that was designed as a “war games” exercise to examine strategic moves in the finance of Medicare. The introductory comments to the exercise excited me when I heard that the objective was to understand what CMS could do to promote the Triple Aim. My excitement was diminished a little when I interpreted comments made by some of the attendees during the opening conversation to indicate that my sense of the Triple Aim was quite different than theirs. “Variation” is an inherent part of everything related to healthcare.

Within the group of attendees there was general consensus on one leg of the Triple Aim. Everybody includes better care for the individual in their personal definition of the Triple Aim, although I did have the feeling that there was some variation in the definition of “better”. Are we looking for “way better”? How about “a little better”? Could we go for “just about the same”? Over the two days of meetings there was rare, if any, reference to the six domains of quality as presented in Crossing the Quality Chasm to define any component of what better care might be like for individuals or populations. You know the reference; care that is patient centered, safe, timely, efficient, effective and equitable. It is unfortunate that it was after the meeting that we learned that the annual count of avoidable deaths from medical errors has topped 250,000 making medical errors the third leading cause of death in the country.

There was also variation in opinions about the expense leg of the Triple Aim. I discover that we are often talking past one another when the subject is “cost of care” or “total medical expense”. It has become fashionable to index increases in cost to increases in our GDP. No one suggested an objective like reducing the medical costs enough, say 10%, to establish healthcare spending at 16% of GDP. There was little enthusiasm for taking on cost with much vigor. The big concern was avoiding lower revenue. Could it be that our collective effort to reduce costs will follow the trajectory of our efforts to improve safety and reduce the number of deaths annually from medical errors?

Finally, the third leg of the Triple Aim, healthier communities where everyone has access to the care they need, may have been amputated. There were vocal advocates for the underserved, but most realistically asserted that the delivery system, and especially individual physicians, were poorly positioned to rid our communities of the disparities that currently exist in healthcare. There was agreement that collective investments from outside healthcare should be made in social services, if we are going to have healthier communities without healthcare disparities. One got the distinct impression that the poor and others who are currently underserved should not expect a resolution of their plight in the foreseeable future. Healthcare is not asking the fundamental questions. What part of the problem are we? We do not readily admit that our addiction to 18% of GDP leaves much for other collective interests. What can we do that might make things better? How can sources (taxpayers) outside of healthcare collectively invest more in our communities and keep up with all of the other “asks” in the public budget if we are spending 18% of GDP on “repair care”?

As the first hour of discussion introducing the exercises came to an end, I had to admit to creeping realism and a growing cynicism. What was going through my mind that perhaps I did not have the courage to point out was that the goal was not really the Triple Aim, but rather a revision which I described as “two heavily qualified hopes and one impossible dream”:

Care for most of us in the future that is about as good as some of us can find now, health that gradually gets better for more people sooner or later, cost that continues to finance the system without much change as long as can be afforded by transferring more resources from other concerns, …for at least eight five percent of people most of the time… with the hope that our grandchildren might be smart enough to do better.

At the end of the exercises on the second day the whole group reflected on what was learned. Below is my random list of lessons learned or reinforced.

- CMS alone can not achieve the Triple Aim.

- Medicare Advantage is growing rapidly and this should be encouraged.

- “Choice” remains a huge roadblock to more efficient and effective care.

- Even Medicare produces bimodal care that has less equity than one would expect.

- Physician, hospital, and health system autonomy is as big or even a bigger barrier to the Triple aim than patient choice.

- CMS has been wise to reach out to other payers to create a long term strategy to try to eventually move all of the delivery system to risk based population models.

- People are using concierge medicine as a threat to fend off delivery system transformation.

- Fee for Service will be hard to kill and will persist for many years even within bundled payment mechanisms and ACOs.

- Funds for the teaching and research missions of academic medical centers should be carved out of the dollars spent for healthcare delivery and put into separate budgets or finance systems.

- We need more vigorous partnerships between healthcare providers and institutions with the communities they serve, if we are going to improve the health of communities. There is not really much incentive now for that to happen.

- Despite resistance, alternative payment models are becoming the shared objective of CMS and many, if not most, payers. It is only a matter of “how much time”. The goal is 50% of healthcare finance in APMs with risk by 2018.

- The ACA may go, but APMs are here to stay and grow despite the mixed results of the various Medicare and Commercial ACOs.

- The underserved and marginalized will remain underserved and marginalized for a long time. DSH hospitals and the funding of Medicaid will continue to be afterthoughts in most local medical economies until the initiative to address these concerns is taken away from local and state government.

- Primary Care compensation will improve but specialty compensation will not fall without a fight that would have few survivors.

- We are not yet ready to make difficult decisions together and as a result by the time we are, there will be fewer options.

I keep thinking of more items to add to the list, but there is more on it now than can be addressed in many years. I feel that one huge benefit to the exercise was to realize that we have overcome a lot of resistance and there is some momentum for change. That momentum is jeopardized by endlessly renegotiating many of the things we thought were already settled.

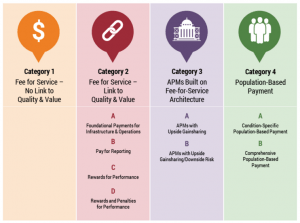

Prior to the exercise I had not discovered the work of the The Health Care Payment Learning & Action Network (LAN). You will have a much clearer glimpse of the future that CMS and large national payers are advocating if you spend a little time on their website. The LAN is a collaboration between CMS and commercial payers. Its goal is to have 50% of all patients, not just Medicare recipients, in risk based products by 2018. Its “Work Group” was charged with creating an alternative payment model (APM) Framework that could be used to track progress towards payment reform. That work is pictured below.

The white papers and graphic material on the website explain the vision and reveal that the ultimate objective is for payment to be–risk based and/or capitated. I for one support the goal of moving payment toward risk and capitation but am concerned that we will be back to “gate keeper” models if we do not include quality, patient satisfaction and self declared outcomes as parameters in the finance systems of the future.

The Work Group has developed a working definition of person centered care that included both patients and providers. Their definition is a little different from the way clinicians look at patient centered care. Remember that the group is primarily composed of executives from insurance entities, employers, and patient advocates. . They write:

The Work Group believes that person centered care rests on three pillars: quality, cost effectiveness, and patient engagement. [It is]: high quality care that is both evidence based and delivered in an efficient manner, and where patients’ and caregivers’ individual preferences, needs, and values are paramount.

The Work Group’s recommendations must be balanced between the needs of both of its customers, patients and providers. This definition makes further sense because the HPC-LAN Work Group is a collaboration of public and private payers. In a very direct articulation of purpose this collaboration between CMS and insurers states:

The Work Group is committed to the notion that transitioning the U.S. health care system away from fee for service (FFS) and towards shared risk and population based payment is necessary, though not sufficient in its own right, to a value based health care system…

We are moving into a world where increasing clinical complexity must be recognized as a source of expense and frustration for clinicians whose work in primary care and cognitive specialties is neither appreciated or supported financially.

The work group states in their excellent executive summary:

To ignore the needs of clinicians and institutions is not conducive to the delivery of person centered care because it does not reward high quality, cost effective care. By contrast, population based payments … offer providers the flexibility to strategically invest delivery system resources in areas with the greatest return, enable providers to treat patients holistically, and encourage care coordination…the Work Group and the LAN as a whole believe that the health care system should transition towards shared risk and population based payments.

After the coalition states their intent they expound on their foundational principles:

- Changing providers’ financial incentives is not sufficient to achieve person centered care, so it will be essential to empower patients to be partners in health care transformation.

- The goal for payment reform is to shift U.S. health care spending significantly towards population based (and more person focused) payments.

- Value based incentives should ideally reach the providers that deliver care.

- Payment models that do not take quality into account are not considered APMs in the APM Framework, and do not count as progress toward payment reform.

- Value based incentives should be intense enough to motivate providers to invest in and adopt new approaches to care delivery.

- APMs will be classified according to the dominant form of payment when more than one type of payment is used.

- Centers of excellence, accountable care organizations, and patient centered medical homes are examples, rather than categories, in the APM Framework because they are delivery systems that can be applied to and supported by a variety of payment models.

These seven bullets get a little wonky toward the end but I appreciate the Work Group’s intention of being transparent at all levels. The list as a whole returns us to Dr. Robert Ebert’s pronouncement from more than fifty years ago. We are still searching for an operating system and a finance mechanism that meets the needs of the population.

What we have learned is that we may need several aligned operating systems and supportive finance mechanisms to serve multiple populations whose needs differ in a variety of dimensions including the geography and the services available. Where do we go next? Is it more important to build the delivery model (operating system) or conceptualize the optimal finance mechanisms? Both jobs are hard and if I learned anything at all at the “war games”, it was that if we hope for a better future that includes the goal of the Triple Aim, we must do both and there must be different options negotiated and ready for choice in each market.