August 11, 2023

Dear Interested Readers,

Continuing Memories From Medical School

Medical school was many things. It was a huge vocabulary lesson. It was an introduction to professional life. It was formative and transformative. When I look back on my four years in medical school there were many meaningful events, but a few that stand out in my memory above all others events that are either forgotten or have become blurred and faded.

Neuroscientists have postulated that beyond repetition there are at least two other factors that solidify memories: novelty and dopamine. My story last week about the first day in medical school scored on both those points. There was “novelty” for sure. You only have one first day of medical school. When I heard the thud of some of my classmates passing out it is quite likely that the dopamine levels in my hippocampus went through the roof. A quick scan in my mind of those formative and transformative experiences that moved me from someone who wanted to be a doctor to someone who could rightfully apply the prefix to their name does reveal many days when there was either a lot of novelty in my experience or substantial surprise, excitement, or more often, fear that sent a wave of dopamine across my hippocampus.

Chronologically, I experienced the next big combination of novelty and dopamine very shortly after that first day of medical school. We were all assigned an individual advisor. My advisor was a very busy young hematologist at Children’s Hospital. I was given his name, vague directions to his office, and an appointment to see him late one midweek afternoon.

For those not familiar with the Longwood Medical Area in Boston. If you were standing at the intersection of Avenue Louis Pasteur and Longwood Avenue in 1967, the Quadrangle of buildings that are the heart of Harvard Medical School is directly in front of you looking West. Behind you is the skyline of downtown Boston, the Fenway, Emmanuel, and Simons Colleges as well as Boston Latin and Boston English High Schools. To your immediate left was the Boston Lying-In Hospital, the Harvard Dental School, and the Mass College of Pharmacy.

Straight ahead after walking through the Quadrangle, you would be at the Frances Countway Library ( I was told that it was second only to the Library of Congress as a medical library.) and the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, Brigham and Women’s Hospital since the early 80s. To your immediate right would be Vanderbilt Hall, the student dormitory. Across Longwood Avenue and a block to the right were the complex of Children’s Hospital, The Jimmy Fund Building, and The old House of the Good Samaritan where the victims of rheumatic fever were treated. Behind the Children’s Hospital as you walked down Shattuck Street toward the Countway Library, with the back of the Quadrangle on your left, and the backside of the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital on your right you would pass the rather modest buildings of the Harvard School of Public Health.

If you continued down Lonwood past the Children’s Hospital for another block you would come to Brookline Avenue. Across Brookline Avenue and to the left another block was the New England Deaconess Hospital then home of the Lahey Clinic and the Joslin Clinic. If you turned right onto Brookline Avenue and walked past the Massachusetts College of Art, you were in front of the Beth Isreal Hospital where that big event on my first day of medical school occurred.

To finish off the “lay of the land” of this unique medical world you needed to look up and beyond the Quadrangle to the Southeast and Mission Hill which was crowned by The Robert Breck Brigham Hospital For the Incurables which by 1967 specialized in the treatment of bone and joint diseases and the New England Baptist Hospital which the Lahey Clinic used along with the New England Deaconess for general medical care. The Longwood Medical Area was an amazing place to be in 1967. I was impressed by who was there and had been there. It was a place that had produced almost two centuries of awe-inspiring accomplishments. Within about one square mile or less, there were some of the best-known sources of medical care and medical research in the world.

But there was and is more to Harvard’s sources of medical training in Boston. The Massachusetts General Hospital, Mass General, or as most locals refer to it, the MGH, frequently referred to by those who worked there and others as Man’s Greatest Hospital, was a few miles away on the Charles River at the foot of Beacon Hill. Even closer was the Boston City Hospital with its Thorndike Lab. Both of these hospitals were huge parts of Harvard’s domain even if they were at a distance from the quadrangle.

Boston’s dominance of healthcare in 1967 was built on more than the reputation of Harvard Medical School. Boston University (BU) and Tufts both had exceptional medical schools, dental schools, hospitals, and Schools of Public Health. The Boston City Hospital was a very unique environment in 1967 in which all three of the medical schools provided teaching “services.” I had my medical school “Introduction to the Clinic” and surgical rotations at the “Boston City.” On a Saturday night, there was plenty for a medical student to see and do in the Emergency Room of the Boston City Hospital. Working at the BCH was great preparation for my years of moonlighting in emergency rooms of hospitals in the suburbs early in my career.

Across America, there are many huge medical centers. In my mind, the only one that approaches or exceeds what I experienced in 1967, is Houston’s “Texas Medical Center” which claims to be the world’s largest medical complex. If you click on the link, you will see 2.1 square miles of high-rise hospitals and clinics where more than 20.000 doctors do research and provide care in “21 hospitals and eight specialty institutions, eight academic and research institutions, four medical schools, seven nursing schools, three public health organizations, two pharmacy schools and a dental school.” Unlike the Longwood Medical Area in Boston which felt to me like it was integrated into the neighborhoods around its perimeter, the Texas Medical Center felt to me “like a world apart” when I visited it a few years ago. I guess my feelings and memories about the Longwood Medical Area have always been a combination of awe for the history and accomplishments that have occurred there and confusion about how I got there topped off with frequent novel experiences and served up with generous portions of dopamine.

When I headed out to see my advisor I was not as familiar with the lay of the land as I came to be over the next four years. I was totally dependent on the skimpy written directions that I had been given. I had never been to Children’s Hospital and was not quite prepared for the size or complexity of the Institution. As just a part of the area, it was a unique world for a young man from a small city in the South. It was an entire hospital just for children that was at least twice or maybe three times larger than any hospital that I had ever entered.

After inquiring at the information booth near the main entrance, I was directed to a bank of elevators. I was told that my destination was in the basement. That was information that seemed strange, but I accepted it and proceeded on my journey as directed.

For the remainder of this story to make sense, I need to introduce some information about polio that I have reviewed in several previous letters written around the pandemic. COVID-19 was not the first time in my life that I had serious fears about an epidemic of infectious disease or great relief from a novel vaccination. I have written about the polio epidemics of the first half of the twentieth century and the flare of concern that I had when many of my classmates were afflicted in the mid-fifties before the Salk and Sabin vaccines. Perhaps my most complete description of polio, as I experienced it, is to be found in the post of March 21, 2021. Suffice it to say, One of the happiest days of my elementary school days, a day of novelty and dopamine, was the day my class lined up for our polio vaccinations. Those memories were triggered by the relief of getting my first COVID vaccine from a member of the New Hampshire National Guard after sitting in a line of cars in the parking lot of a local community college thirty miles from my home.

The lady at the information desk pointed me to a bank of elevators. I pushed the “Down” button and in a moment entered an elevator alone where I pushed the button for the basement. When the elevator doors opened I was definitely in the basement of the Children’s Hospital, and I was alone. I was clueless as to whether I should turn right or left. There were boxes, empty beds, rubbish bins, and other hospital detritus lining the dark hallway. It was immediately clear to me that I was now on my own. My directions gave me only a room number at the Children’s Hospital, and the lady at the information desk had not said whether to turn right or left after I got off the elevator when it reached the basement. It seemed that I had two options, I could go back to the lobby and ask again, or I could start exploring. My wife says that it is a “guy thing” never to go back, and being a typical guy I started exploring. By this time I am sure my dopamine levels were rising because I did not want to be late for my appointment. I wanted to make a good impression on my new advisor who would be the first faculty member that I had personal contact with since my disastrous interview with the master of stress interviews, Dr. Daniel Funkenstien, which I described in my letter two weeks ago.

If memory serves me well, I think that my tack was to the left, but it soon became obvious that to the left there was nothing but other storage rooms, more boxes, and out-of-service hospital equipment. I retraced my steps to the elevator and discovered that the hallway branched. Should I go left or right? With no signage as a guide, I went right which brought me to two big double doors. By now I was getting quite concerned that I was lost in a maze and wasn’t even sure that I could get back to the elevators. I had only a brief hesitation at the doors. When I opened them I found myself standing on a platform that had stairs that descended down a few steps into a very large room. As I stood on the platform, I was amazed by what lay in front of me only a few feet below where I was standing. The closes thing in memory to the moment as I stood on the platform and looked out was the first time I looked over the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. What I saw almost defied belief. There were dozens, if not hundreds, of iron lungs. I stood there in shock I remembered my classmates who did not return to school in the fall after getting polio in the summer. At that time there was no way to know that twenty years into the future and to this day I would know and at times provide care for sufferers of Post Polio Syndrome, which seems to me an extension of cruelty because it results in further debilitation of those who thought they had recovered or who had learned to live with their disability.

I don’t remember how long I stood there, but I do remember thinking about how much the world had changed for the better in the ten years or so since I had my vaccination for polio. I don’t know if I pontificated to myself at the time about the power of scientific inquiry. I knew very little then about the ups and downs of testing the vaccine. It would be years before I learned about the “Cutter Incident” where there had been a terrible error that resulted in more than 200,000 people being injected with live virus as test volunteers. I also did not know then that the vaccine would have never been a possibility unless John Enders, working with Fredrick Robbins and Thomas Weller at the Children’s Hospital had not isolated the virus. Ender’s received the Nobel Prize and generously included his colleagues.

After a partial recovery from the shock of my discovery, I continued my search for my advisor’s office. His office was a little further down on the road to the left not previously taken when I chose to go down the short hallway that lead through the double doors to my remarkable discovery. As I have relieved the memory over the years, I am surprised that I don’t remember telling my advisor about my discovery when I eventually did find his office. He was a junior faculty member, probably a research fellow or Instructor, who was not long out of training himself. I barely remember him and remember nothing of our meeting. I may have had one follow-up meeting a few months later. I can’t be sure. If it was a novel encounter, my dopamine discharge at the sight of the iron lungs probably left little neurotransmitter in reserve to expend on my encounter with him. The other uncertainty in my memory was whether I ever went back to see the iron lungs again to contemplate the combination of misery and hope that they represented. I think that I did a few years later when I was rotating through the Children’s Hospital as part of my cardiology fellowship at The Brigham. If I did, I am sure that they were gone.

That visit to my advisor was only the first of several memories from my medical experiences at Children’s Hospital. I had an excellent clinical pediatric clerkship there, but my most transformative experience was a longitudinal experience during my last two years of medical school working in the Children’s Hospital Family Healthcare Unit of Dr. Joel Alpert which was housed in a little building across the street from the House of the Good Samaritan and the Jimmy Fund Building just a few steps down the street from Shattuck Street. The little building is long gone. It and other structures were replaced by a huge facility to generate heat and electricity for the medical area, but that little office building with its exam rooms and conference rooms was where I had some of my most formative experiences.

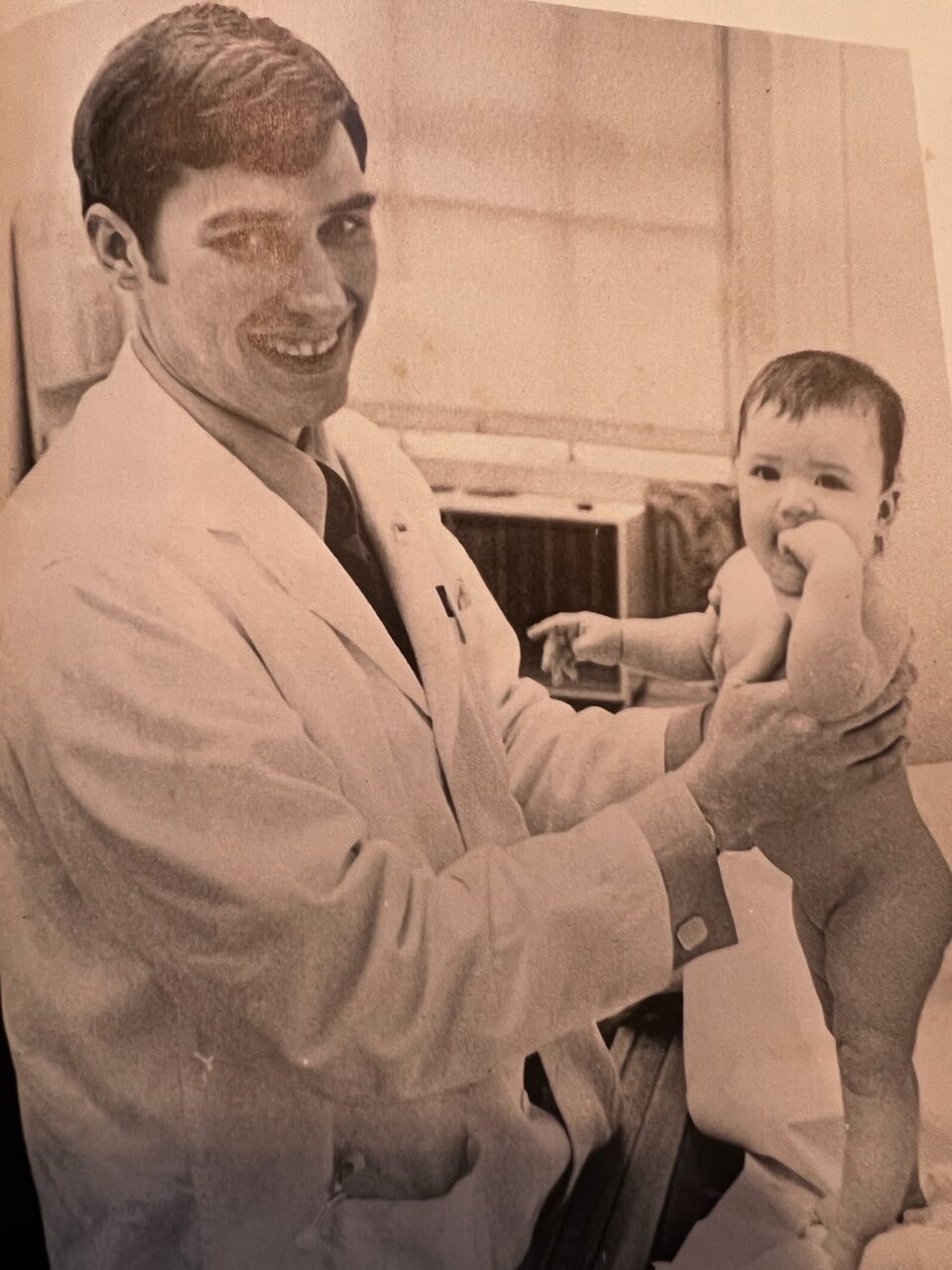

Each of the participating students followed a few families from the Children’s Clinic longitudinally. “Clinic patients” were a fundamental asset to medical education. The families I followed would now probably be Medicaid recipients. They came from the tenements on nearby Mission Hill. One family, in particular, remains in memory because the mother suffered from Munchousen’s Syndrome By Proxy. Ironically, the child who was the victim and focus of factious disease is pictured with me in a photograph in the Aeculapiad, the “yearbook” of my graduating class in 1971.

It took me and my advisors several months to recognize that the origin of the child’s many symptoms including the ingestion of foreign objects like safety pins were manifestations of his mother’s mental illness.

I was so excited by my experience that I was an enthusiastic applicant for the new combined training program that was proposed between Children’s Hospital and The Peter Bent Brigham Hospital. The program was designed to prepare its participants to take the boards in both medicine and pediatrics as a high level of competency in Family Medicine. My enthusiasm dimmed when I learned that Dr. Alpert who was the heart of the program was going to the Boston City Hospital as Chief of Pediatrics. (You should click on the link and learn more about this remarkable man.) I guess that a little of Dr. Alpert’s advocacy for primary care and universal access to healthcare rubbed off on me. After I heard that Dr. Alpert was leaving Children’s Hospital for a professorship at Boston University and Boston City, I dropped my plans to apply to the joint Children’s and Brigham program and applied for a medical internship at The Peter Bent Brigham Hospital where I had done my medical school rotation in medicine.

I experienced the combination of novelty and dopamine often in medical school. The road toward a career in medicine is long, and medical school is just one long lap. There are scores of remembered events and even more that I am sure were contributors to who I am but are long forgotten. There are a few more events from medical school that I want to share with you next week before moving on to the intense post-graduate years.

“Hospital Days” In New London

The header for today was taken last Saturday on the town green in the midst of the annual “Hospital Days” events. “Hospital Days” have occurred every year on the first weekend in August for longer than I can remember. Over the first weekend in August, there are many events designed to raise funds for our local hospital which is now affiliated with Dartmouth Health. “Hospital Days” events were canceled in 202O and 2021 because of COVID. Before this year there was a “mini-triathlon” as part of the celebration. What has survived is the big parade down Main Street and the events on the Commons.

For several years I have marched in the parade either as part of Kearsarge Regional Ecumenical Ministries or as a participant from my church. Since I am the “moderator” of the church I marched behind the church banner as you can see in the picture below.

I thoroughly enjoy the small-town atmosphere and the collective efforts to help our community. I am not sure how critically dependent our hospital is on the revenue from “Hospital Days” but I do know that all small-town hospitals face enormous challenges. Perhaps the biggest yield from the celebration is not the money, but it is the collective effort that binds us together to support a shared community asset. It’s also a lot of fun for everyone!

I hope that you will enjoy some beautiful weather this weekend. I hope to spend a lot of time on the lake with friends. There are only four weekends until Labor Day. Enjoy them all!

Be well,

Gene