August 7, 2020

Dear Interested Readers,

The Pandemic’s Message To Us About Healthcare Policy

Earlier this week in a post entitled “The Peril We Face Has Been A Long Time Coming,” I reviewed an excellent article by Ed Jong who writes for The Atlantic. As I said then, I believe that Jong’s overview articles about the pandemic present a remarkably insightful review of why the pandemic has occurred, why we weren’t prepared for it, why we have not managed it well despite having enormous resources and expertise at our disposal, how the president’s actions and inactions have made it worse than it had to be, and what the possible outcomes will be as we look into the future. This latest article of Jong’s was entitled “How the Pandemic Defeated America: A virus has brought the world’s most powerful country to its knees.” My use of the article went in several directions that were driven by Jong’s analysis of this very complex moment in history.

My father occasionally made pithy observations about me that would sting when I first heard them, but over time and with much reflection have made me more self aware. One such comment was, “Gene, you mount your horse and ride off in all directions!” I always thought the phrase was my father’s original creation until I Googled it and discovered that a Canadian humorist, Stephen Leacock, not my father, was the likely origin of it. Leacock was a remarkable man who was a politician, a professor of economics at McGill, but most famous for being a very funny popular author of the early 1900’s. In the Wikipedia link you will discover:

It was said It was said in 1911 that more people had heard of Stephen Leacock than had heard of Canada. Also, between the years 1915 and 1925, Leacock was the most popular humourist [English spelling] in the English-speaking world.

Leacock influenced American humorists Robert Benchley, Groucho Marx, and Jack Benny. The phrase about riding off in all directions comes from Nonsense Novels published by Leacock in 1911. In the chapter entitled “Gertrude the Governess or Simple Seventeen,” Leacock writes:

Lord Ronald said nothing; he flung himself from the room, flung himself upon his horse and rode madly off in all directions.

The phrase seems to have had some fame, perhaps it was even a meme during my father’s childhood. It certainly remained “active” in Canada where “Madly in All Directions” was a long running radio production. I have even discovered that it has been used by a minister in a daily devotional.

I think that dear old Dad was right about me and heading off in all directions. That charge can frequently apply to my writing as it did in the latest post. When life gets crazy and I find that I am over committed or that I am tiring from having “too many plates spinning in the air,” I can still hear Dad’s admonition to “slow down” and simplify. Writing about the pandemic takes you in many different directions because it is such a complex subject, is associated with so much uncertainty, and is forcing so much immediate and long term change. It is more than an immediate threat to individual health, to our collective economy, and a compelling reason to reject our current president and the divisiveness in our country that has grown to threatening dimensions over the last fifty years. We stand at a crossroads. We are enlightened by the devastation we observe, and we are frozen by the uncertainty of what to do next.

Jong took us in many directions in his article. You might remember the list I transferred from his piece:

- A sluggish response by a government denuded of expertise allowed the coronavirus to gain a foothold.

- Chronic underfunding of public health neutered the nation’s ability to prevent the pathogen’s spread.

- A bloated, inefficient health-care system left hospitals ill-prepared for the ensuing wave of sickness.

- Racist policies that have endured since the days of colonization and slavery left Indigenous and Black Americans especially vulnerable to COVID‑19.

- The decades-long process of shredding the nation’s social safety net forced millions of essential workers in low-paying jobs to risk their life for their livelihood.

- The same social-media platforms that sowed partisanship and misinformation during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in Africa and the 2016 U.S. election became vectors for conspiracy theories during the 2020 pandemic.

Like most physicians I know, I try to keep up with at least reading the table of content of the New England Journal of Medicine each week. My batting average in regards to perusal of the Journal has improved with the extra time available in retirement, but as I have filled my free time with community activities that have ramped up during the pandemic, I find that I frequently miss reading the Journal on the day it arrives in my mailbox. Such was the case with the July 30 edition. I read it on August 5 and was delighted to find a “Perspectives Article” entitled “Health Care as an Ongoing Policy Project” by Eric Schneider, MD, and an editorial by Dr. Schneider, Debra Malina, Ph.D., and Stephen Morrissey, Ph.D., entitled “Fundamentals of U.S. Health Policy — A Basic Training Perspective Series.” I needed to tell you that I had not read these articles before the last post because my post contains some of the same content.

The editorial begins with the same quote from Paul Batalden that I had used. I wrote

The great physician and advocate for continuous improvement, Paul Bataldan of Dartmouth, has reminded us frequently that “Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.” The results we see as the hospitalizations and death rates from COVID-19 climb, are in large part attributable a system that has designed itself through decades of seeking profit from healthcare delivery while the public clamored for lower taxes, and the budgets for public health were slashed to provide a few shekels of extra money to reduce the burden on taxpayers of providing everyone with a healthy environment, and personal access to care.

The editorial connects the reality that I was describing to “health policy” or more realistically to the lack of a consistent health policy. A you know I like to use bolding to draw your eye to the important points.

It has been said that every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets. The strengths, weaknesses, flaws, and complexity of every health care system stem in large part from health policies. The U.S. health care system did not arise randomly but through a series of deliberate policy choices, many of which have come with unintended consequences. Efforts to reform our system over the past century reveal the ways in which Americans think the system has fallen short. They also reveal what we hope our health care system will do for us.

My cynicism would have forced me to have added that the driving forces were rarely patient centric. More often they were heavily biased toward the financial and scientific interests of the establishment, and far from the six tenets of quality: the pursuit of patient centeredness, safety, timeliness, efficiency, effectiveness, and most lacking, equity. The “Perspectives” article had begun with yet another recounting of the sad state of American healthcare viewed from through the consideration of outcomes, cost, and equity.

The lead article, which was written to launch a new series of articles on healthcare policy, begins with the case of an elderly woman with preexisting conditions trying to decide whether to seek help for her URI symptoms which may be from COVID. There are many barriers she must consider and her path to care is delayed in a way that is the primary determinant of her outcome. From that case Schneider launches a thoughtful presentation about why we are at a critical juncture where policy matters.

…all is not well in U.S. health care. Despite these assets, the United States lags behind other high-income countries on health outcomes such as life expectancy, childhood health, and avoidable deaths. For too many Americans, the quality of care is not optimal. Access to basic care is out of reach for many. The costs of care, escalating for decades, are increasingly intolerable to those who pay the bills, whether governments, employers, or individuals. American health care is also inequitable, with gaps in insurance benefits and quality of care consigning people of color, people living in poverty, residents of rural areas, immigrants, and LGBTQ people to worse care than others. Many gaps widened even while the nation was prospering. The Covid-19 pandemic is bringing these and other weaknesses of U.S. health care into stark relief. Americans have struggled for over a century to solve this riddle and bring about a high-performing, affordable health care system. Some progress has occurred, but many Americans believe that additional reforms are needed.

Comparing the United States with other countries can shed light on both challenges and opportunities for improvement. All countries seek to optimize the population’s health at a cost that people and their nations can afford. Measuring and comparing the health outcomes achieved offers a useful starting point for evaluating how delivery-system performance influences health. To produce better health outcomes, the key areas of performance include the structures that support care (the workforce and organizations that deliver care, and payment systems); the processes used to deliver safe, effective, patient-centered care; and whether people have timely access to that care. Crucially, care should be delivered equitably.

Following that description which we have all heard in various forms and with supporting data on countless occasions since the publication of Crossing the quality Chasm in 2001, Schneider reminds us that every other prosperous nation gets much better outcomes for half the price, and then he further reminds us of how we differ from so many other advanced nations.

Countries embrace various values in determining whether health care is a right, the minimum level of care that everyone must receive, how much variation in outcomes or access to accept, and who will shoulder the costs. Different populations may have different views about the role government should play as a regulator, payer, and operator of health care facilities. They also differ on the role of taxes and other financing mechanisms that pay for care.

That is a small paragraph packed with a lot of meaning that condenses over seventy five years of controversy into three sentences. Anyone who has been a part of healthcare for the last fifty years knows, whether they admit it or really care that:

Many preventable conditions go untreated… On average, U.S. maternal and infant mortality rates are higher than those in many other countries. For a population facing such formidable health challenges, access to care is a key problem. The United States lacks the universal insurance coverage available elsewhere. Public insurance programs cover the elderly, disabled, and poor, but publicly insured patients struggle to find clinicians, particularly specialists, willing to accept them because the government pays lower rates than commercial insurance. As the current pandemic illustrates, the tie between employment and private health insurance means that millions of Americans can lose coverage during periods of economic recession and growing unemployment. Out-of-pocket costs have been rising, too, as high copayments and deductibles — designed to make consumers more cost-conscious — have proliferated. Many Americans fear unexpected medical bills and debt.

The questions that really need answering are why have we allowed these things to happen, and why do we tolerate the expense, the failures, and the inequity. Why are we so stymied in our efforts to fix it? The answers are buried deep in our culture, history, and collective prioritization of the individual as self-reliant and individual rights a more powerful design priority than the health of the community. The outcome of the interaction of the factors is an ineffective, but costly system that has inequity born of individual and institutional self interest at its rotten core.

Americans face pervasive disparities in care based on gender, race, ethnicity, income, educational attainment, language, and neighborhood. Disparities have been documented on most available measures, including access to care in general and to specialty and surgical care in particular, screening rates, diagnosis, treatment, and chronic disease management. Biases are reflected in structural features of the system, including the lower payments, resources, and capital available to clinicians and hospitals serving marginalized communities. They are also revealed in biased decisions about diagnosis and treatment and in too many failures to provide patient-centered, culturally competent care.

Despite the gaps in quality, access, and equity, the United States is on track to spend more than $4 trillion on health care in 2020 — nearly one fifth of all economic activity, as assessed as a proportion of GDP. …Health care spending may create a drag on the nation’s economic power and global competitiveness. And it dampens other investments the country could make to improve the quality of life, siphoning away potential investments in education, housing, transportation, and economic development that may be more powerful determinants of population health.

If you go back to Jong’s list of issues that COVID-19 has capitalized on to wreck it’s havoc on this moment, you will see that Schneider has commented on most of them either directly or indirectly.

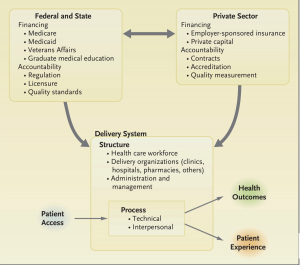

He presents us with a diagram, copied below, that shows the basic components of how our public/private partnership is supposed to work. The reasons that it doesn’t work are two fold: inadequate funding of the public side with many Americans without access to care, and a lack of patient centeredness with much associated ineptitude in the organization and management of a system set up with price and profit as the driving forces. We have placed an undeserved confidence in “the market” to fix the problems of healthcare, as we have underfunded the ability of an increasing number of Americans to participate in a market. Any potential benefit in the design has been lost to established self interest. As a nation facing the challenge of providing health to its population, the powerful among us have mounted their stallions and ridden off in their self interested directions leaving the underserved, the primary providers of essential services plus the “least of these” among us, a worn out old mule to try to ride. Should what we now see really surprise us?

Simple Schematic of the U.S. Healthcare System:

Schneider offers us a less caustic analysis that is a little closer to how we think the system should work:

Government has a crucial role, even in systems dominated by private-sector insurers, delivery organizations, and professionals. Governments license and regulate, set quality and safety standards, and either operate public delivery systems or pay private organizations directly or through insurance programs. Some amount of government subsidy is inevitable to ensure access to care for people who cannot afford it. Governments may use their purchasing leverage to negotiate prices and payments. And they have a key role in preparedness to respond to disasters like the current pandemic.

…Private enterprise and competitive markets capitalize and manage large parts of the system, drive innovation in diagnostics and therapeutics, and create insurance products that cover benefits and services. Functioning private markets can reduce costs and innovate in ways that broaden service availability. But private markets may not restrain costs in health care as they do in other sectors…As the Covid-19 pandemic painfully reveals, in health care, markets can fail to allocate resources to meet health needs, preserve the quality of care, and achieve desired levels of access and equity.

Nixon’s chief economist, Herb Stein, famously advised us that if something can’t go on forever it won’t. I dream and hope everyday that we are standing on the threshold of a new experience in health care. Perhaps COVID-19 has given us a gift. Is this the moment when something that can’t go on forever dies? Is this the moment of dramatic change, the beginning of the end that I have dreamed of for over forty years, or is it the cliff from which we fall into an abyss of even greater misery?

The president came into office making many promises. Business oriented people were happy to have a pragmatic businessman at the helm. Maybe they thought he would be a political Henry Ford, Lee Iacoca, or Jack Welch, all of whom in retrospect, had their flaws. They were blind to his many bankruptcies, and didn’t subject his claims of great wealth to much scrutiny. What we got was a hack reality show star, trying to play the role of a business tycoon, and it has been a rolling disaster. His only accomplishment of note is to pass a tax law that advantaged himself, his family, wealthy individuals, and corporations while undermining the resources to provide healthcare, housing, education, and infrastructure improvements for decades. With a majority in both houses of Congress during his first two years, his administration was unable to craft a healthcare bill that fulfilled his vague campaign promise to offer something better. His reelection can only insure that as we approach the moment of change we will take the path in healthcare that profits a few while further damaging everyone else.

The ACA started out with an infrastructure built on the principles of quality, safety, and preventive care that had evolved over the 90s and the first decade of this century. It was a big step, though incomplete, toward universal access to care. What came out of the legislative process was marred by compromise that stripped out a public option, but it was a step forward. It was an honest effort to see if a public/private partnership built on a market chassis could work. Private forces damaged it before it became law, and it has been relentlessly attacked and diminished as law even as it has provided some relief. The road up has a second fork, to the right is a revamped ACA, to the left, or if you prefer progressive side, is universal coverage through public finance. Both will be incremental steps that will take at least two years to begin to implement. Against those realities, Schneider, writing as a policy participant writes;

Americans are increasingly concerned about health care. Polls show that they are especially dissatisfied with the costs they face personally. Many Americans have begun to view high-quality health care as an opportunity available only to some people, a financial burden for many, and an unsafe and financially ruinous ordeal for others. But a health care system is not immutable. It can be changed through policies. In future articles in this series, experts will further describe the problems with quality, equity, and cost; explore solutions; and reflect on the policy levers that can help bring about reforms.

I look forward to all of those articles. Schneider chose to end the lead article on a high note:

The Covid-19 pandemic reminds us that the dedicated health professionals delivering care every day are the indispensable part of any health system. Without their motivation and dedication, access to high-quality, equitable care would not be an option. But sound health policies are also indispensable. They shape the delivery system, strongly influencing whether someone like the elderly woman with chronic health problems and new and worrisome symptoms decides to suffer at home, delaying until it is too late, or seeks care when it can be most effective. And health policies set the terms under which health professionals can provide high-quality care that achieves her health goals at a price that she and society can afford.

I began with the first paragraph of the accompanying editorial. The last paragraph is too good to miss because it underlines the task for this moment which is to view the upcoming election as an opportunity to return to effective policy formation that may offer hope for a better system of care for everyone in the future.

We find ourselves in the midst of an unprecedented public health crisis, an accompanying economic crisis that has cost millions of Americans their jobs and health care coverage, and a crisis in racial justice that is shining a harsh light on disparities in health and health care. As the U.S. elections approach, incumbent and aspiring policymakers at all levels must grapple with the far-reaching implications of the design and reform of our health care system. Physicians and other health care providers have an opportunity to influence the policies that shape the system in which they work. We hope to offer a foundation for a common understanding of where we stand and where we need to go.

How Does Your Garden Grow?

My wife loves her cat and her garden. I know my place in the order of her priorities and am quite happy to be settled in comfortably behind more important entities. A realistic assessment makes me try harder. I think that I am moving up the list, but I have a way to go.

Today’s header shows her raised bed garden, and the love of her life, Lily the cat. Lily likes to snooze in the afternoon sun near the garden. If you look closely at the picture you will see her. She is sunning herself on the gravel path. The shadow of the vegetation makes finding her a little like “Where’s Waldo.”

Lily was not always an outdoor cat. In Massachusetts she was always indoors. In New Hampshire she kept “escaping,” usually my fault for not securing the door. Eventually my wife decided that we would all be happier if we accepted that keeping Lily indoors was a failed endeavor. Even now she is not really an outdoor cat. I would call her an indoor cat who asks to go outdoors or come indoors about fifty times a day. One of the strategies that I have learned to move up my place on the list of my wife’s interests is to be willing to drop anything to hop up and open the slider for Lily to come in, if she is out, or to go out, if she is in, and wants out. Lily has not learned to do her business outdoors which has offered me another strategic opportunity for advancement. In retirement I have become very good at managing all aspects of the kitty litter process.

August is the time of the big garden harvest. We have had plenty of herbs and kale for a long time, but now we are moving into tomatoes, peppers (really hot ones), cucumbers, and other garden delights. Perhaps someday she will give corn a try, but for now the local supply is bountiful and is less than a dollar an ear at our favorite farm stand. It is hard to consider growing our own corn since limited production would make our product cost us about $20 an ear if the same math that applies to tomatoes was transferred to corn.

How does your garden grow? Do you have a cat? In the hierarchy of your household what is your status? I hope that you are as happy and fulfilled as I am.

Be well! Still stay home if you can. When you are out and about, wear your mask and practice social distancing as best you can. Don’t try to outguess the virus.Think about the America you want for yourself and others. Demand leadership that is empathetic, thoughtful, truthful, capable, and inclusive. Look for opportunities to be a good neighbor. Let me hear from you. I would love to know how you are experiencing these very unusual times!

Gene