My wife and I were recently watching the PBS program “The Vote” when it occurred to me how long it takes to achieve social change. The story of Women’s Suffrage is an international saga that really spans a few thousand years. It was not until 2015 when Suadi Arabia extended the right to vote to women that every country on the planet that held elections granted women the right to vote. As I ran with my thoughts, I reviewed the long history of the struggle for human rights. The simple right to own one’s self, to profit from one’s own labor, to make choices about who we chose to love and share our lives, to speak our opinions without fear, to worship as we wish or decide for ourselves if there is a God or not, and the right to vote, are all examples of rights that have been “won” after a long struggle with a powerful status quo that had an apparent advantage in denying the desired right to everyone.

Missing from my list of rights that have been “won” is the right to healthcare. It seems to me that some “rights” cost other members of society if they are to be extended to everyone, and some don’t. It doesn’t cost me anything for you to worship or not. It did indirectly cost part of the status quo something for women to vote because women did vote against alcohol and prostitution. Ta-Nehisi Coates has demonstrated that slaves were the single most valuable asset in America before the end of slavery and freeing the slaves cost the agrarian South billions of dollars in “lost property.”

It occurs to me that “what it seems it will cost” to some vested interest, or all of us collectively, is a major source of resistance from many of us to improving the “social determinants of health.” The idea that “what it will cost some individuals” is obviously an oversimplification of the resistance to providing adequate education, universal access to humane housing, clean water and air, meaningful employment, protection to the environment, and universal healthcare. For the social determinants of health to improve there will be a need for many changes of attitude and perspective, and perhaps at the core of the resistance is the fact that improvements of the social determinants of health will require a “transfer of wealth.”

How wealth is transferred is a big part of politics. The phrase usually suggests an increase in taxes for some coupled with grants of resources to others. It is the rare individual who doesn’t think twice about the idea of paying more taxes to benefit someone else. Again, I apologize for over simplification, but ever since we began to focus on owning property and growing personal wealth about ten thousand years ago there has been tension between individual ownership and the common good.

Many years ago (probably sometime between 1978-83) I read an article in The New Republic about the class system in America. The article suggested that it was an oversimplification to conceptualize a lower, middle, and upper class in America. The article suggested that there were several gradations of “middle class” that could be distinguished by employment, education, personal choices, and a variety of other descriptors. “Artists” of all descriptions: writers, actors, painters, dancers, musicians and the like, were in a parallel position to the class structure. The final two classes, the very poor and the very rich, were described as “up and out of sight” and “down and out of sight.”

The author implied that both groups, the up and out of sight and the down and out of sight, shared two characteristics. Most of us did not “see” members of either group, and both groups were “supported” by society. The lower class was supported by welfare financed from tax revenues. The upper class was supported by wealth earned through the dividends of their investments and the advantages of the tax system which gave them the benefit of the work of others. I am not saying that I ascribe to the analysis, but it does seem interesting as a potential explanation for what we see, and it is not inconsistent with the evolution of inequity as described by Thomas Piketty in his book, Capital in The Twenty First Century.

Big changes in society, social structure, and human rights can occur in sudden and unexpected ways. The coronavirus and the COVID-19 pandemic surprised most of us even though something like it had been predicted and Bill Gates had famously advised us to get ready for what was inevitable. Even more of a surprise was the widespread reaction to the death of George Floyd. The killing of a Black man by the police was not a surprise, what was a surprise was the brutality of the act and the repugnance that its brutality elicited from so many people from very different backgrounds. In this one brutal event many people saw what they could no longer deny, just how disgusting our founding defect has always been.

How often have you heard the phrase “the new normal” and wondered just how long it would take to reach it?” It was beginning to be clear that a return to normal was unlikely before the recent explosion of new infections in the previously spared South, Midwest, Southwest, and West. The accelerated appearance of new cases is clearly a manifestation of our loss of discipline, our impatience and frustration with the pandemic’s “cost to the economy,” and the personal inconvenience that many experienced when asked to do their part and follow recommendations that might limit the spread of the virus. The president’s lack of understanding and incompetence multiplies the uncertainties about how to manage the virus. His demand that we return to acting like things are “normal” derives not from his sense of responsibility but from his need to get re elected, and the arrogance of his fatal misconception that the right to demand that a virus go away is a presidential power, like providing clemency to your felonious friends.

As I write, California is back in a virtual lockdown, and Florida, Texas, and Arizona should be. There are 36 other states where rates of infection and death are rising. It is staggering to realize that 3.3 million people have been infected and that over 135,000 have died. It is highly likely, virtually unavoidable, that we will have seen more than 150,000 deaths by Labor Day. It is frightening to contemplate how many more lives may be lost by year’s end. An interesting question that keeps coming up is whether this moment is a “second wave” of the pandemic or an extension of the “first wave.” Does it really make a difference since we have no vaccine and only partially effective treatments?

Since the near future is uncertain, and the near past is beyond modification, it makes sense to review the inadequacies of our current system of care, and then think about the “new normal” that we would like to have replace what has failed us. On June 25th, The New England Journal of Medicine published a perspective piece entitled Covid-19 and the Need for Health Care Reform that was written by Jaime S. King, J.D., Ph.D., a professor at the University of California Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco. Professor King began by focusing on the inadequacies of our current patchwork system of healthcare coverage. We have a porous system that is a combination of employer-sponsored health insurance, the ACA exchanges, Medicaid, Medicare, and the VA medical system. Despite spending more per capita by a wide margin than any other country on the planet, we have at least thirty million people without any coverage and more than forty million more who are inadequately covered. He writes of the pandemic related inadequacies of our current system of care.

Before the pandemic, research showed that more than half of American with employer-sponsored health insurance had delayed or postponed recommended treatment for themselves or a family member in the previous year because of cost. The loss of jobs, income, and health insurance associated with the pandemic will greatly exacerbate existing health care cost challenges for all Americans. For instance, in a recent poll, 68% of adults said the out-of-pocket costs they might have to pay would be very or somewhat important to their decision to seek care if they had symptoms of Covid-19.2 Failure to receive testing and treatment because of cost harms everyone by prolonging the pandemic, increasing its morbidity and mortality, and exacerbating its economic impact.

That last sentence is worth repeating because it is the economic principle that should drive the design of the “new normal.”

Failure to receive testing and treatment because of cost harms everyone by prolonging the pandemic, increasing its morbidity and mortality, and exacerbating its economic impact.

We live in a complex interconnected world. The pandemic has demonstrated that what harms you often reverberates in my life. Not spending money on worthy projects or underfunding the social safety because of the cost to those who have the ability to pay produces problems that cost us all more in the end than providing a universal benefit would have cost. That was a point that Bernie Sanders kept trying to make that seemed difficult for anyone to understand. His timing was off. He spoke too soon.

Professor King continued by reviewing the support provided to health care by The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and by changes in the payment processes of Medicare and Medicaid. What is lost in the review of large numbers is that Congress is offering many millions of dollars of support, but our annual healthcare expenses are measured in trillions of dollars. I serve on two boards of healthcare institutions, The Guthrie Clinic, located in the small town and rural environment of the Twin Tiers of northern Pennsylvania, and southern New York, and the Boston University Medical Group which provides the professional coverage for the Boston Medical Center. Money from the CARES Act and other federal sources have been helpful, but have not come close to replacing the losses experienced by either organization for which I have a fiduciary responsibility. If there is anything that the pandemic has demonstrated to me, it is the inadequacy of a fee for service payment system to meet the challenges of a pandemic. In the “new normal” I would recommend the benefit to everyone of a system of healthcare that provides universal coverage and adequately funds institutions for the effectiveness and quality of care provided to a population.

Once again, what we needed to meet the challenges of the pandemic was not new information. Much of the advice that would have made management of care for everyone better during the pandemic has been on our bookshelves since 2001 when Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century was published. As we make plans for our “new normal” we already have a pretty good blueprint.

At the end of his piece Professor King offers advice that is overdue:

…Never before has the interdependence of all our health, finances, and social fabric been so starkly visible. Never before has the need for health care reforms that ensure universal access to affordable care for all Americans been more apparent. Our policies on health and health care, both during this pandemic and in the future, should reflect this reality, and we should not let the lessons of this crisis pass us by.

We have paid, and will continue to pay dearly as a nation our lack of preparation and the shortsightedness of our self interests. Let’s heed Professor King’s sage advice which is in essence a repeat of Winston Churchill admonition to “never waste a good crisis.”

Back in March, in the earliest moments of the pandemic, Dr. David Blumenthal, the president of the Commonwealth Fund, and Dr. Sara Collins, a healthcare economist who is also Vice President of the Commonwealth Fund discussed our deficient preparation for the challenge ahead. It’s an interesting podcast to review now four months later. The previous link will take you to the transcript. In the conversation, Dr. Collins, an expert on our system of coverage, expressed her concern that people who might be infected would delay getting care.

SARA COLLINS: That’s right. So what’s concerning both for people who might become infected and for people that they share a community with, is that people who become infected with a highly contagious virus might not seek care. And as David mentioned, the people who are most vulnerable to this are older people, people with underlying health conditions.

So even if you’re younger and uninsured, you might not get care and it might not affect you very much, but that might have serious implications for someone who’s older who might catch it from you.

Once again, it’s sad to say that we knew the problem, but did not act on it. Now with more than three million cases we have not gotten much better. Dr. Blumenthal made a follow up comment that is worth presenting as an indication of what should change if we ever get to a “new normal.”

DAVID BLUMENTHAL: I’d like to add another point to the underpreparedness of our health care system, and that is that we don’t have adequate primary care in the United States. We have a tremendous deficit compared to other advanced countries of frontline providers who can offer that initial contact with the health care system, where symptom identification can take place, and where screening could happen outside of the crowded and more dangerous setting of a hospital emergency room.

Dr. Collins then adds depth to the understanding of how inadequate our patchwork system of care is and how prone it is to letting people who need care slip through its coverage defects. The lack of treatment or the delay in treatment that the lack of coverage creates will eventually damage the health of others.

SARA COLLINS: That’s right. In the United States, by law, people with incomes under 138 percent of poverty, which is about $30,000 for a family of four, are eligible for Medicaid, but only if their state expanded eligibility for Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act.

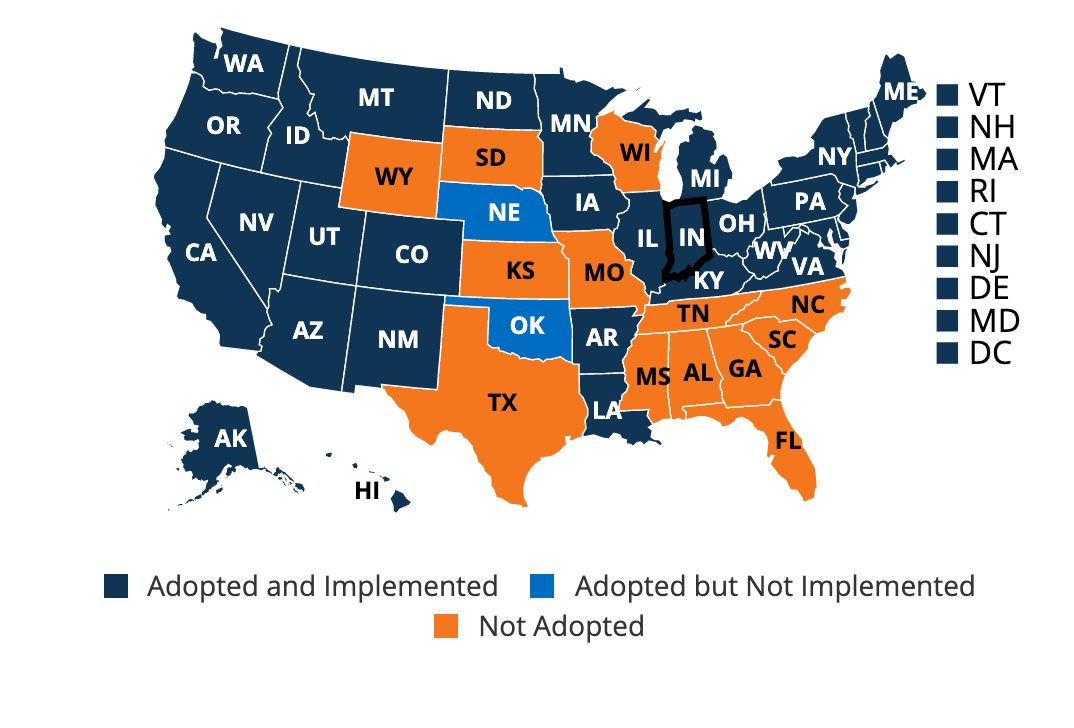

Right now, 36 states and the District of Columbia all have expanded their Medicaid programs. Fourteen states — including some of the most highly populated states in the country, Florida and Texas — have not yet expanded. So people in those states who have incomes under poverty do not have access to an affordable source of health insurance right now.

You might note in the map below from a Kaiser Foundation publication last week that many of the states that did not expand Medicaid under the ACA are the same states whose governors have reopened prematurely and are most aligned with the president’s denials and policies. Is that a surprise? In my mind one characteristic of a better new normal would be the recognition that coverage and coordination of healthcare should occur at a national and not a state level. I would not deny a state like New York, Massachusetts, California, or any state that so desired, the right to do more for their citizens, but the pandemic experience suggests to me that there should be a common “floor” for all states of adequate benefits and controls.

Collins then presents an example of how the Trump administration has made many people who are immigrants afraid to use the benefits to which they are entitled. The so called “Public Charge rule” suggests that those who use public services will have greater difficulty getting citizenship.

The effort to reduce immigrants who are legal enrolled in the program through something called the Public Charge rule, we know that that has also had the effect of putting a chilling effect on enrollment, particularly of children in the Medicaid program.

In response to Dr. Collins’ examples of the system’s failure to effectively serve people in need Dr. Blumenthal says:

DAVID BLUMENTHAL: What has happened is that the mesh of the safety net has developed holes, and people can fall through. It used to be that when they fell through, the consequences were mostly to them as individuals…Now when they fall through, the consequences are very apparent for all of us. Because the illnesses they may fail to get treated or fail to identify are going to spread to people who have felt in the past that it wasn’t their problem.

That’s where I will leave their conversation, the point I am trying to let them make for me is that when we as a nation, in our new state of enhanced experience from the COVID-19 pandemic, sit down to create our “new normal,” we should realize is that even though the “collective good” will necessarily lead to some transfer of wealth the new product will be worth it. We spend hundreds of billions of dollars annually on military defense when more of us are likely to die from a virus than from the act of some foreign power or terrorist.

About a month ago Victor Fuchs of Stanford offered us more advice in a JAMA piece entitled Health Care Policy After the COVID-19 Pandemic.

He began his article by reassuring us that:

….the 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic will end sooner or later as all pandemics do…To simply return to the prepandemic health care system during a presidential election year would be a mistake. This is a time to think more boldly about the future of the US health care system. The health care system is dysfunctional for many individuals in the US; it is too costly, too unequal, and too uncertain in its eligibility and coverage, with an increasing number of uninsured. However, designing and implementing a better health care system will not be easy. In exploring the challenges and difficulties ahead, it is useful to distinguish between those that are primarily technical issues (although these are not exempt from politics) and those that are political obstacles to significant reform.

Under “Technical Issues” he he sees two concerns

- How to raise the nearly $4 trillion each year to pay for US health care

- How to organize and deliver the care and compensate those who provide it.

That sounds fairly similar to Dr. Robert Ebert’s analysis from more than fifty years ago when he wrote that the challenge inherent in achieving better care was developing better systems of finance and more efficient operations with a focus on the needs of a population:

“The existing deficiencies in health care cannot be corrected simply by supplying more personnel, more facilities and more money. These problems can only be solved by organizing the personnel, facilities and financing into a conceptual framework and operating system that will provide optimally for the health needs of the population.”

Fuchs continues:

An important goal of health care reform should be to replace the current byzantine system of premiums, taxes, tax exemptions, deductions, subsidies, and out-of-pocket payments with a much simpler system of financing health care. An equally important goal is to replace the current multiplicity of public and private health insurance programs with 1 universal program that covers everyone from birth to death…universal systems have proven to be the best way to ensure that everyone has access to care without bankrupting individuals or governments.

How to raise the money to pay for health care is important and continues to receive attention. But more important are questions about how to organize and deliver care and how to compensate the individuals and organizations that provide it…

I have long favored “capitation” as the most effective finance model. I am delighted to see that Fuchs shares that position:

Capitation reimbursement provides incentives to use resources efficiently, unlike fee-for-service reimbursement that provides incentives for overuse. This is not just a theoretical proposition. The Kaiser Permanente Health Plan has been paid per capita for more than 50 years and has seen its enrollment increase to 12 million patients, one-third more than in the Veterans Health Administration care system…Physician-led health plans that receive risk-adjusted capitation payment are in the best position to allocate resources more efficiently and effectively according to judgments about benefits and costs.

Fuchs does not go into detail about how he would advise changing the delivery of care, but my experience has led me to believe that physician led organizations capitated to provide measured quality and improved outcomes will continuously innovate to find the best ways to provide care. I offer Kaiser, the old Group Health Plan of Puget Sound, now a part of Kaiser, and my old organization as examples of this reality. There are hundreds more. Fuchs moves on to the political issues to consider in post pandemic policy making:

Changes in the health care system have always been opposed by many. As Machiavelli observed, proposals for a new order face strong opposition from those who benefit from the old order. This group includes high-income patients who prefer a health care system that caters to their interests and values…The cost of this system, more than $11 000 per person per year, is tolerable for those with high incomes, but oppressive to most individuals in the US and ruinous for many, leading to missed medicines and bankruptcy.

Most of us suffer financially in some way or another, sooner or later, from this expensive system that excludes so many. The pandemic is not the first time we have all suffered from the inadequacies of this system, but like the death of George Floyd, it is perhaps the most dramatic example of a problem that we can no longer ignore. Fuchs points out that a barrier to improvement that affects us all is our nation’s congenital distrust of centralized government and its programs. Fuchs senses that things may be changing.

Most voters do not have high incomes, but another major obstacle is distrust of the government by many in the general population. In a Pew Research Center survey from 2017, the public was asked to choose between larger government with more services and smaller government with fewer services. Forty-five percent of 5009 respondents chose smaller government. That sentiment may still be true but may change as current events unfold. Proponents of health system reform should think for ways to reduce, if not eliminate opposition…Distrust of the government is difficult to dispel, but it is possible to do so as President Roosevelt proved with his New Deal reforms in the 1930s. Even though it has seemed that major reform of health care would only occur in the wake of a major war, a depression, or large-scale civil unrest that changed the political balance, it now appears that the COVID-19 pandemic may provide the dynamic for major political change. If that occurs, major health care reform will be more attainable.

I will end this tour of other people’s thoughts about the lessons and the opportunities that our common pandemic experience will make possible with reference to an opinion piece in JAMA from May by the person I consider to be the foremost thinker and activist of my generation in healthcare policy and care improvement, Don Berwick. Dr. Berwick’s article is aptly entitled, Choices for the “New Normal.” Don always begins with a novel observation that draws you into an analysis:

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has only 15 genes, compared with 30 000 in the human genome. But it is a stern teacher, indeed. Answers to the questions it has raised may reshape both health care and society as a whole.

No one can say with certainty what the consequences of this pandemic will be in 6 months, let alone 6 years or 60. Some “new normal” may emerge, in which novel systems and assumptions will replace many others long taken for granted. But at this early stage, it is more honest to frame the new, post–COVID-19 normal not as predictions, but as a series of choices. Specifically, the pandemic nominates at least 6 properties of care for durable change: tempo, standards, working conditions, proximity, preparedness, and equity.

The remainder of the piece is primarily an expansion of each of those six points.

1.“Tempo” becomes the “speed of learning.” He writes:

Will the tempo for learning and improvement be faster in the new normal than before? A famous meme in health services research is that proven, favorable innovations take years to reach scale; one often-quoted study claims that the average cycle time is 17 years. Not in this pandemic.

He elaborates to make his point and then points out: Assumptions are dissolving about how much time progress takes.

2. “Standards,” Don’s second category, becomes “The Value of Standards.” He envisions a change of attitude in the :new normal.”

Clinicians in the new normal may be less tolerant of unwarranted variation in health care practices. The COVID-19 norm is to welcome standardized clinical processes, as opposed to reflex defense of “clinical autonomy” as the primary basis for excellence. The strangeness of the COVID-19 clinical territory leaves even experts looking for guidance from trusted sources. …Will the new normal embrace global learning, shared knowledge, and trusted authority as foundations for reducing harmful, wasteful, and unscientific variation in care?

3. “Working Conditions is expanded as “protecting the workforce.”

…Sadly, attention to health care worker safety has languished at far too low a level of priority for decades. Now it is evident how unwise that is, as millions of workers face personal risks that they would not encounter if protective equipment and preparatory procedures had been arranged in advance. Will the new normal address more adequately the physical safety and emotional support of the health care workforce in the future? Without a physically and psychologically safe and healthy workforce, excellent health care is not possible.

4. The biggest transition in name, if not in reality, between care pre pandemic and the new normal, is what Don calls “proximity.” In his discussion “proximity” morphs into “Virtual Care.” He begins with a historical reference.

Hippocrates saw patients face-to-face, and medical care still mostly relies on personal encounters. COVID-19 has unmasked many clinical visits as unnecessary and likely unwise. Telemedicine has surged; social proximity seems possible without physical proximity. Progress over the past 2 decades has been painfully slow toward regularizing virtual care, self-care at home, and other web-based assets in payment, regulation, and training. The virus has changed that in weeks. Will the lesson persist in the new normal that the office visit, for many traditional purposes, has become a dinosaur, and that routes to high-quality help, advice, and care, at lower cost and greater speed, are potentially many? Virtual care at scale would release face-to-face time in clinical practice to be used for the patients who truly benefit from it.

5. Don expands “preparedness” to “Preparedness for Threats.” There is no avoiding the conclusion that despite clarity about the potential risk for a devastating pandemic, we were totally unprepared, and the initial efforts to establish preparedness made by the Obama administration after SARS, MERS, and Ebola threats were being dismantled by direction from the Trump administration when the pandemic arrived.

As virtual care has lagged leading up to COVID-19, so, even more, has preparedness for 21st-century threats. The foundations of preparedness, most crucially a robust public health system, have been allowed to erode or have never been laid in the first place. Several major reports in the past decade have tried to call attention to that lack of readiness, with only minimal response.5 The COVID-19 toll may be the largest paid so far for this failure, but without taking public health and preparedness seriously, it will be neither the last nor the greatest. Other pathogens, massive trauma, cyberthreats to the electric grid, and more no longer seem so abstract or distant. Will public health finally get its due?

6. Finally there is “equity.” Don was the first person to impress on me the fact that equity was a foundational principle in quality. I suspect that the six domains of quality described in Crossing the Quality Chasm include “equity” because of Don’s participation in the preparation of the book. In the body of the paper Don shifts the term to the shameful reality of the “Inequity” in our pre pandemic model of care. He asks if that changes in the “new normal.”

Perhaps the most notable wake-up call of all is inequality, as the worm in the heart of the world. Students of either health or justice are not at all surprised to read headlines about the unequal toll of COVID-19 on the poor, the underrepresented minorities, the marginalized, the incarcerated, the indigenous peoples…The most consequential question in the new normal for the future of US and global health is this: Will leaders and the public now at last commit to a firm, generous, and durable social and economic safety net? That would accomplish more for human health and well-being than any vaccine or miracle drug ever can.

Don gives us much more, as he does always. I hope that you will read the entire piece for yourself. He congratulates us for our rapid acceptance of social distancing, and for the maintenance of contacts in our businesses and social lives through the rapid deployment of technologies like Zoom. Despite the few, including I might add our president, who seem not to care enough to participate in the sacrifices of convenience for the common good, it has been a time of enormous generosity and participation that reveals what Rutger Brugman would call our basic human nature of “goodness.”

Don urges us to capture what we have learned and move it forward as a positive foundation for the new normal. The picture in today’s header is of the Robert Packer Hospital in Sayre, Pennsylvania. I took the picture on a dark overcast day before the pandemic, and before we realized that the time we had to repair our healthcare deficiencies before there would be an enormous price to pay was running out. As a member of the board of the Guthrie Clinic, and its five hospitals, I sense that during the pandemic many of the six components of Don’s vision of the “new normal” have become embedded in the future of the organization. What would assure that these positive changes can persist will be the changes in public policy that guarantee the right of every person access to care that is patient centric, safe, timely, efficient, effective, and equitable. In a post COVID-19 new normal world we have a renewed opportunity to see the wisdom of making that vision a reality. There are many practical and political bridges to cross on the long journey to a new normal, but don’t let anyone tell you that we should not attempt to make the trip because we can’t afford it.

The single most important lesson that we should learn from the pandemic is that everyone must be included on the journey to the new normal. The old normal was a flawed reality that has become uninhabitable.

Don is much more eloquent than I am, so I will let his closing words from the article finish this post. I added the bolding to emphasize his most important point.

Fate will not create the new normal; choices will. Will humankind meet its needs—not just pandemic needs—at the tempo the COVID-19–related morbidity and mortality demand? Will science and fact gain the high ground in guiding resources and behaviors? Will solidarity endure? Will compassion and respect be restored for the people—all the people—who make life agreeable and civilization feasible, including a guarantee of decent livelihoods and security for everyone? Will the frenzied world of commerce take a breath and let technology help simplify work without so much harm to the planet and without so much stress on everyone? And will society take a break from its obsessive focus on near-term gratification to prepare for threats ahead?

Most important of all: Is this the time for equity, when the evidence of global interconnectedness and the vulnerabilities of marginalized people will catalyze at last the fair and compassionate redistribution of wealth, security, and opportunity from the few and fortunate to the rest? This virus awaits an answer. So will the next one.