Change is slow, and time flies. It has been twelve years since 2007, and changes that were discussed then are still works in progress now. 2007 was a big year for me. I did not know it, but 2007 would be my last year of full time practice and part time leadership as the Chair of the Boards of Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates and Atrius Health. 2007 was the year that the Triple Aim was being organized as a concept at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The Triple Aim would be formally published in Health Affairs in 2008 by Berwick, Nolan, and Whittington not long after I switched from practicing to the role of CEO of HVMA and Atrius Health. I was full of good intentions and had a bubbling enthusiasm to make Atrius a paragon of quality and a leader in the march toward the Triple Aim.

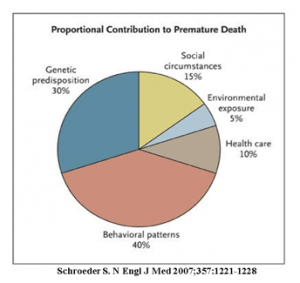

As I began my new role I was fortunate to be working with Zeev Neuwirth who was our Vice President for Clinical Improvement and Innovation. Early on in our partnership while we were writing a strategic plan to guide our efforts, Zeev showed me a recent article from the New England Journal written by Steven Schroeder and entitled We Can Do Better — Improving the Health of the American People. It had been published in September of 2007 and was the transcript of the 2007 Shattuck Lecture of the Mass Medical Society. As I look back on my first introduction to the article I realize that it was a transformative experience for me. What I read was consistent with my experience in practice, but it also suggested that we needed to begin to think differently about our future. I immediately began to use a slide taken from the article in almost every presentation I made inside or outside of our practice.

Schroeder showed data that we have now seen so often that I fear we pay it little attention. He showed us that we lagged behind other developed nations in multiple metrics including life expectancy and rates of infant mortality. His conclusion was:

When it comes to reducing early deaths, medical care has a relatively minor role. Even if the entire U.S. population had access to excellent medical care — which it does not — only a small fraction of these deaths could be prevented.

We did not have as robust a vocabulary about the “social determinants” of health in 2007 as we do now, but Schroder spent a lot of time connecting poor outcomes and early death to social and behavioral issues. He then expressed a conclusion that still holds true.

Since all the actionable determinants of health — personal behavior, social factors, health care, and the environment — disproportionately affect the poor, strategies to improve national health rankings must focus on this population. To the extent that the United States has a health strategy, its focus is on the development of new medical technologies and support for basic biomedical research. We already lead the world in the per capita use of most diagnostic and therapeutic medical technologies, and we have recently doubled the budget for the National Institutes of Health. But these popular achievements are unlikely to improve our relative performance on health. It is arguable that the status quo is an accurate expression of the national political will — a relentless search for better health among the middle and upper classes.

In essence he was saying, “You can’t get there from here.” It is quite interesting to note that Don Berwick made exactly the same point in his recent IHI lecture, “Start Here: Getting Real About Social Determinants of Health” that I wrote about in last Friday’s Healthcare Musings. Twelve years is a long time, but apparently it is not long enough for the sort of changes that Dr. Schroeder was advocating. Schroder anticipated that he would need to defend his point of view so he asked the question,

“Why don’t Americans focus on factors that can improve health?”

His answer:

The comparatively weak health status of the United States stems from two fundamental aspects of its political economy. The first is that the disadvantaged are less well represented in the political sphere here than in most other developed countries, which often have an active labor movement and robust labor parties. Without a strong voice from Americans of low socioeconomic status, citizen health advocacy in the United States coalesces around particular illnesses, such as breast cancer, human immunodeficiency virus infection and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV–AIDS), and autism. These efforts are led by middle-class advocates whose lives have been touched by the disease…the biggest gains in population health will come from attention to the less well off, little is likely to change unless they have a political voice and use it to argue for more resources to improve health-related behaviors, reduce social disparities, increase access to health care, and reduce environmental threats. Social advocacy in the United States is also fragmented by our notions of race and class.To the extent that poverty is viewed as an issue of racial injustice, it ignores the many whites who are poor, thereby reducing the ranks of potential advocates.

The relatively limited role of government in the U.S. healthcare system is the second explanation. Many are familiar with our outlier status as the only developed nation without universal health care coverage. Less obvious is the dispersed and relatively weak status of the various agencies responsible for population health and the fact that they are so disconnected from the delivery of health services.

Schroeder’s second explanation, the ineffective role of government has been improved somewhat by the passage of the ACA in the interim although those gains are threatened. The point that is as true today as it was twelve years ago is:

Less obvious is the dispersed and relatively weak status of the various agencies responsible for population health and the fact that they are so disconnected from the delivery of health services.

Schroeder did not know that Obama would be elected fourteen months later, or that he would sign the ACA on March 23, 2010, so he advised that in the absence of much help from politicians it was the responsibility of physicians and other health professionals to lead the way. The picture at the top of this note shows the hopeful crowd in Grant Park that cheered Obama on the night he was elected. We have now earned that we need more than a courageous political leader. We must be actively involved in the creation of change. As Schroder said:

…it is incumbent on health care professionals, especially physicians, to become champions for population health. This sense of purpose resonates with our deepest professional values and is the reason why many chose medicine as a profession.

A recent article in the New England Journal was what got me thinking about Schroeder’s Shattuck Lecture again. I could feel Schroder’s message being upgraded for this moment in time in a short “Perspectives” article, “Focusing on Population Health at Scale — Joining Policy and Technology to Improve Health.” Whether the authors, Aaron McKethan, Ph.D., Seth A. Berkowitz, M.D., M.P.H., and Mandy Cohen, M.D., M.P.H. ever read Schroder’s 2007 article or not, they offer us ideas that fit well with Schroder’s observations about the ineffectiveness of bureaucratic efforts to improve the nation’s health.

They begin with observations that seem right out of Schroder and Berwick.

Progress in biomedical innovation and technology has resulted in unprecedented improvements in human health. But population health is influenced by more than medical technology or health care services. Socioeconomic, psychosocial, and behavioral factors — including access to basic needs such as food, housing, and transportation — are major contributors to health and cost outcomes.

They suggest that we have programs created by public policy that are not well integrated and are therefore not as effective as they could be. They present as an example of their point the reality that half of the nearly 60,000 annual births in North Carolina in 2017 were paid for by Medicaid, but 31% of those mothers were not enrolled in the WIC program for which they are eligible. The criteria for enrollment are such that if a mother qualifies for Medicaid she should also qualify for WIC benefits. WIC is a successful program that provides benefits during the critical period before age five. We are making an error in management when a mother on Medicaid is not also receiving WIC benefits.

What gives? Basically, we seem to be inept. We can create programs that we know can help but they are poorly integrated and much potential benefit from the synergy of coordinated efforts is lost. They point out that we are good at doing pilot programs that prove the efficacy of a social policy, but not so good at scaling up those programs and integrating them into a sustainable approach that works to improve health and lower the cost of care.

Our new payment models are public policy attempts to encourage program innovation that moves us toward the objectives of the Triple Aim. They feel that our lack of expertise in the effective use of information technology in government programs and in the private sector explains some of our failure. To be successful in reaching the goals we have set “will require new ways of thinking, collaboration, and accountability on the part of both health care and government leaders.”

They make three suggestions to improve the benefit that we extract from the programs that we have created and that are currently funded.

1) Human services programs that support health-related needs (those directed at the social determinants of health) must be more effectively integrated “into a systematic population health approach.”

Such a strategy should not mean creating additional tasks for busy clinicians — primary care physicians should not manage SNAP enrollment, for example. Rather, there is a need for coordinated workflows that facilitate identification and enrollment of eligible patients. These arrangements can be accomplished only with direct collaboration among health care provider organizations, payers, community organizations, and government agencies.

2) We should “ promote both policy and information-technology innovations that make program enrollment seamless. …but putting such approaches into practice has not been easy. For example, eligibility criteria for Medicaid and SNAP use different definitions of a household, which creates a substantial barrier to simultaneous enrollment.

3). We should agree that “policymakers should explicitly consider the effects of human-services programs on health and total cost of care. This approach will require developing rigorous evidence regarding the combined effects of health care and human-services programs as well as evaluations of new ways to integrate such services.

It is hard to believe that there are still those who do not recognize the tight association between successful social programs, the total cost of care, and the health of the nation. Our success will require winning the argument that better social programs coordinated with better access to care are necessary for a better future for us all. Healthcare leaders must make this point and help to create a bipartisan recognition of the reality that…

As health care payments are increasingly tied to population-level outcomes, the sustainability and effectiveness of human services should be an increasingly important priority for health care leaders. SNAP resulted from a political coalition of rural, conservative advocates for farmers and urban, liberal advocates for alleviating poverty; we envision a similar partnership between health care leaders taking on risk for population health and cost-related outcomes and human services leaders supporting the same populations. Increased bipartisan advocacy and support from health care leaders could help improve the political stability of human services programs and encourage innovations that enhance their effectiveness…

They end with a warning and the possibility to choose a better future:

…Failure to make practical progress on these steps risks undercutting the value of our large and growing investments in health care services. But getting them right will enable a coordinated system that uses all available avenues to improve the health of populations.

We have known what to do for over a decade. Knowing and doing are not the same.