For more than four years I have had a visceral reaction to red hats with bold letters spelling out Make America Great Again. Occasionally, the hat’s message may be reduced to the acronym MAGA, or some combination of MAGA and Trump. Theoretically, there is nothing negative about the phrase or the acronym, but both have acquired a patina of meaning, and the sight of the hat causes my blood pressure to rise as I begin to project negative feelings about the person wearing the hat. Each time it happens I can feel a gulf forming between me and the individual who is proudly wearing the hat, and I know that I am a part of our national problem.

This problem of alienation and separation from some neighbors, some friends, and some family, has consequences at several levels. First, there is the sense of sadness and alienation that I feel. Second, there is the loss of what could be a sustaining relationship. Third, the summation of millions of these small rifts adds up to a “house divided.” President Lincoln warned us that “a house divided against itself cannot stand.”

I feel that we face an enormous number of issues that impact the health of the nation that cannot be effectively addressed until we build bridges that establish a more effective partnership that is less bipartisan. I am not a “Pollyanna” and I know that we have not reached the nadir of our separation, but I am hopeful that it’s not too late for us to recover if recovery and harmony is what we want. I have seen us come together after storms and after attacks on our collective security.

I have always felt that the challenge to the individual is to ask, “What part of the problem am I?” Ghandi is reported to have said that we should be the change we want to see in the world. When I think about what I can do I realize that I should begin to try to control my own sense of separation and seek to become a better neighbor. An individual can not change the reality of the national statistics on the diseases of despair. One person alone cannot improve the social determinants of health for a large population. One person can make a difference in the life of one other person or family. As clinicians we are trained to be patient centric, and if we carry those skills into our community we might make a difference as “better neighbors.”

I have always been intrigued by the wisdom of Dr Ebert. He did nothing that was not part of a larger objective. It did not take me long to realize that even the name he chose for our organization had deep meaning. “Harvard” spoke to expertise. There is often the sense of a rift or separation between expertise in universities and the communities where they are located. He must have been aware of that separation when he put the words “Harvard” and “Community” together. I would like to think that in some way it was an expression that Harvard was a part of the community and wanted to be a good neighbor. I think that he convinced Nathan Pusey, the president of the university, of the wisdom of the idea. Pusey was one of Ebert’s greatest supporters, and the launch of HCHP would not have been possible without the collaboration of these two men against the resistance of those whose worldview did not include the university’s responsibility to be a good neighbor and member of the community. It amuses me that many of their detractors in the mid sixties pointed to the word “community” as evidence that the organization was an exercise in “socialized medicine,” and warned that it was the first misstep on the brink of a “slippery slope” to things that would be worse.

I am sad to say that when I first saw American flag lapel pins they generated in me a sense of separation, and a fear that we might be on the first step of a rightward slide toward some more authoritarian state. To my relief, Democratic politicians now wear them too, but my memory suggests that they began with those politicians who wanted to make a statement that raised questions about the patriotism of those who did not wear one. I was given an American flag lapel pin, but sadly I do not have the inclination to wear it because, like the MAGA hat, others might think that I am signaling support for a set of ideas that I feel run counter to my affection for “these truths.” The two words “these truths” always elicit a reflex recitation from me of the whole sentence from which they are lifted:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

I have had my reactions to these challenges. You might remember my green Make Earth Cool Again hat which was the header for a piece last June about the “Green New Deal.” My response to American flag lapel pins is to try to reclaim the flag by flying it prominently throughout spring, summer, and fall from a flagpole at the end of my dock. I recognize the right of everyone to exercise free speech in all of its manifestations, and assert my equal right to present the flag in a way that I believe is most consistent with my interpretation of the meaning of our shared national national icons.

At the president’s more recent campaign rallies, like the one held last week in Iowa, we see plenty of Make America Great Again hats plus an updated slogan, “Keep America Great.” One of my promises to myself for this year of tension associated with impeachment and the continuing process to select the next president has been that I am going to work on controlling my emotional response to the visual clues that divide us.

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky taught us about “thinking fast and slow.” The Wikipedia summary of the thesis of the book that Kahneman wrote about the two ways we think is instructive of the fact that how we think contributes to our biases.

The central thesis [of Kahneman’s book, as well as the Nobel Prize winning work of Tversky and Kahneman] is a dichotomy between two modes of thought: “System 1” is fast, instinctive and emotional; “System 2” is slower, more deliberative, and more logical. The book delineates cognitive biases associated with each type of thinking…

American flag lapel pins, MAGA hats, pictures of Mitch McConnell, Lindsey Graham, and Donald Trump generate “System 1” thinking in me. I have come to realize that when I respond to a flag pin or a MAGA hat with System 1 thinking, which is a “knee jerk response,” I am stereotyping the wearer of the pin or the hat. Stereotyping is foundational to developing biases, and biases lead to division, seperation, and isolation. I must use slow thinking to avoid the traps associated with these triggers of my emotions. If I use System 2 thinking, which is slower, more deliberative, and more logical, I am more likely to look past the flag pin, the hat, or the obvious differences that exist between myself and the other person, and warn myself that I need to be careful not to focus on our differences that will generate a bias within me. If I work hard to overcome my System 1 response, I might discover that there is much that we share. If there is no earthly thing in common between us, we are still both created with the same potential rights. We are brothers and sisters both created by a common reality that is beyond our mundane disputes.

I recently had a real life test of my ability to recognize my vulnerability. As part of my work with a charitable organization called Kearsarge Neighborhood Partners, I have been helping an elderly man organize his finances. I enjoy our relationship and we have developed some trust and rapport. Today as I was giving him a lift to an appointment, he began to talk about how sad he was to hear that Rush Limbaugh has cancer. He went on to say how much he admires him and how import Fox news was to him, since he lives in the country, can’t drive, and spends his day watching Fox News and listening to talk radio. It was a test for me. Is this man my neighbor?

If I go back to the sentiment and analysis presented in our Declaration of Independence, I am reminded that we are equal in our creation, and in our birthright to life, liberty, and happiness. I will extend those rights to include that we are free to choose where we get our news and whom it is that we admire. I am reminded that though there are differences in many of the superficial descriptors that define us there are more important things that we share in common, and that my preferences and priorities should be equally weighted with those of any other individual. My vote should not count more than the vote of my friend who can’t drive and watches Fox News.

Most religions and most cultures emphasize that we should treat one another as neighbors and that we should express generosity to strangers. Most of these sources of wisdom suggest that we should respond to neighbors and strangers with the hospitality and concern that we would like to receive in return. This primary rule assumes reciprocity and its wisdom predates history and writing. There are elements of its wisdom in the Code of Hammurabi that is almost 4000 years old. Indeed, some say it is the most important principle in the foundation of a successful society. It could be called life’s most important piece of “game theory.” Most of us learned it as some variation of “Do unto others as you would have them to do unto you.”

Recently I have been reading the latest book by a very interesting woman, Barbara Brown Taylor. You can get a flavor of her and her wisdom by listening to an interview from last spring with Terry Gross on the NPR program “Fresh Air.” Near the end of her recent book, Holy Envy: Finding God in the Faith of Others, Taylor writes eloquently about how almost all religions celebrate the principle of the Golden Rule and its relationship to diversity, being neighbors, respecting those who are not like us, and what we must overcome if we are to move toward a sustainable world. To understand the beginning of the quote you need to know that her husband’s name is Ed. She writes:

Now Ed and I operate by our first amendment to the Golden Rule, which is not “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” but “Do unto others as they would have you do unto them (instead of thinking they are just like you).”

Taylor makes some fundamental points about what we experience and what the common wisdom of our diverse human cultures advises. Her writing leads me to ask questions like “Who is my neighbor?” I wonder if “neighbors” and “strangers” are synonymous. Do both qualify as the “others” in the Golden Rule? How do neighbors, strangers, and others line up with our divided nation? Should these ideas be given some consideration as we think about the Triple Aim, our relationships with patients and colleagues, and the future of healthcare?

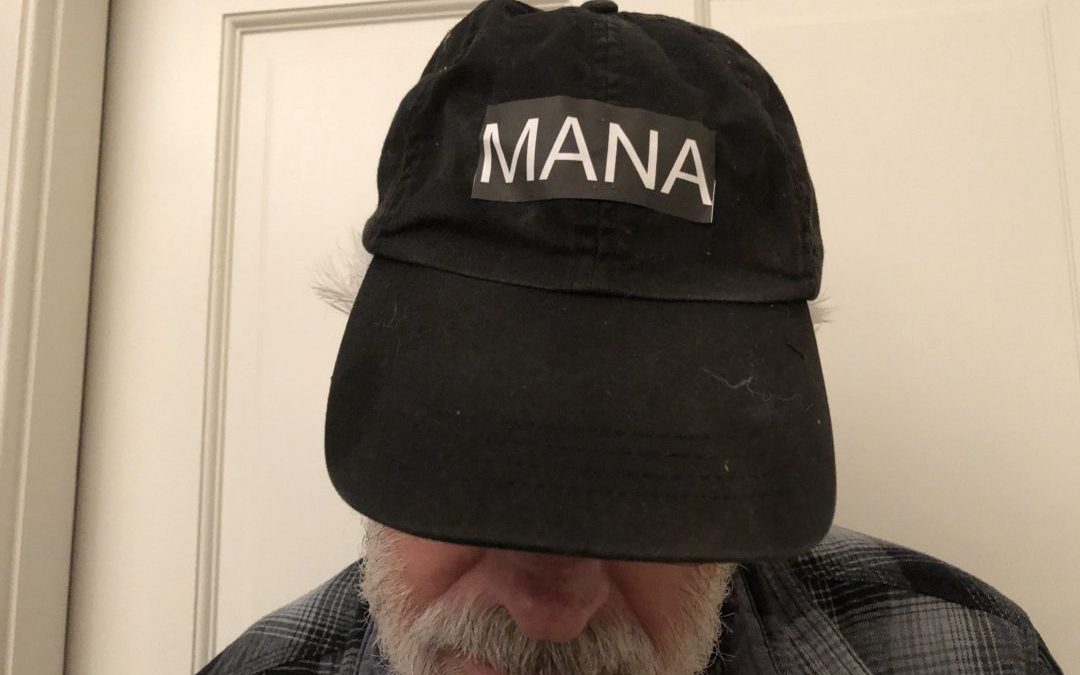

I assume that you are wondering about the point I am trying to make with my new hat which you can see me wearing in today’s header. I should say that it is a “prototype.” The acronym on the hat, MANA stands for Make America Neighborly Again. It is my personal opinion that making America great or sustaining its greatness requires that we improve our skills at “neighboring” and accepting people who differ from us as worthy of our care and concern. It is my belief that if we want America to be great and healthier, the job of becoming great would be easier, more likely, and if achieved, more likely to be sustained, if we embraced a culture of being neighborly.

I am a regular watcher of the evening news. My preferred vendor of the evening news frequently ends the broadcast with a story of “neighborly” behavior. Some of the stories bring a tear to my eye, and I am filled with hope that these are more than reports of rare incidental behavior. I want to believe that all of us would respond to a person in need. As I have begun to do more charitable work in my town and region, I come across evidence that many of my “neighbors” are abused by landlords who charge them enormous penalties for a few days of delay in payment of their rent. There are many “poverty” penalties that seem to be the opposite of “neighborly” behavior. The movie version of Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy is in theaters now. It describes an environment where many are not treated by the Golden Rule. Maid: Hard Work, Low Pay, and a Mother’s Will to Survive is the memoir of a young single mother trying to lift her daughter and herself out of poverty. She was more often treated as an obnoxious “other” than as a neighbor in need. Evicted: Poverty and Profit In the American City by Matthew Desmond is an indictment of our collective inability to extend to some of our neediest citizens the security of housing even as we spend tens of billions more on middle class homeowners in the form of tax deductions for their mortgages. Is that neighborly? We all know that there are 30 million Americans who do not have basic access to healthcare, the number grows by millions more if you add our undocumented neighbors, and by tens of millions if you add those who have inadequate coverage. Is that neighborly? Are these realities consistent with “these truths” which we hold dear as a manifestation of our shared creation?

Many people made fun of Marianne Williams when she ran for the Democratic nomination for the presidency, but she did call us to be better neighbors. Cory Booker also reminded us of our responsibilities to one another, but his message and his candidacy never gained traction either. Was it because he made too many references to love and his neighbors? I do believe there are active candidates for president who are presenting ideas that will move us toward greater equity in income and access to healthcare, and that is good. My hope is that this election will move us toward greater equity and opportunity for everyone, and that we will continue to grow in our understanding that ultimately, in terms of our economic security, we are collectively no more secure than our least secure neighbor. In terms of our health, the health of our neighbor has a huge impact on our own health. It is hard to image that a country that could put a man on the moon more than fifty years ago could be suffering from an epidemic of gun violence and diseases of despair. I hope that we will soon realize that if we are more focused on what divides us than what we can share together as neighbors who care about each other and our planet, our future is in jeopardy. Lincoln was right to warn us that a house divided against itself is not healthy and it is vulnerable to the diseases of a society that could bring it down. I just can’t believe we will let that happen, especially if we each commit ourselves and our enterprises to being “neighborly.”