Most of the big issues that we fret about seem far beyond our individual ability to make a difference. It is hard for us to look at a big societal issue and imagine just how our individual contributions can matter. I worry about climate change and hope that my efforts to reduce my carbon footprint will sum with your efforts, and the efforts of others, both here and around the world, to make a difference. I vote and ask others to vote knowing that taken alone my vote is only a statement of personal opinion that can only create change when it is added to your vote. In the same way a bold audacious goal like the Triple Aim requires a collective effort to have any chance for success.

There are many reasons that our enthusiasm for difficult objectives can be overwhelmed beyond an understandable sense of futility: “What’s the use? I can’t make a difference.” Frustration from sense that as an individual we lack the power to make a difference is only the beginning of the long list of reasons we can develop that suggest that only a zealot would get involved. Almost always there is a personal cost to joining the effort for improvement. To deny global climate changes is to free yourself from the expense of mitigating your carbon consumption. Al Gore was on to something when he talked about “An Inconvenient Truth.” To admit that there are too many guns in the world, including the half dozen that you own, creates a reason for action that has a personal expense. Realizing that “we can’t get to the Triple Aim from here” without “transformational change” will mean more work for you, and “what’s the use?” since the objective won’t be achieved before you retire.

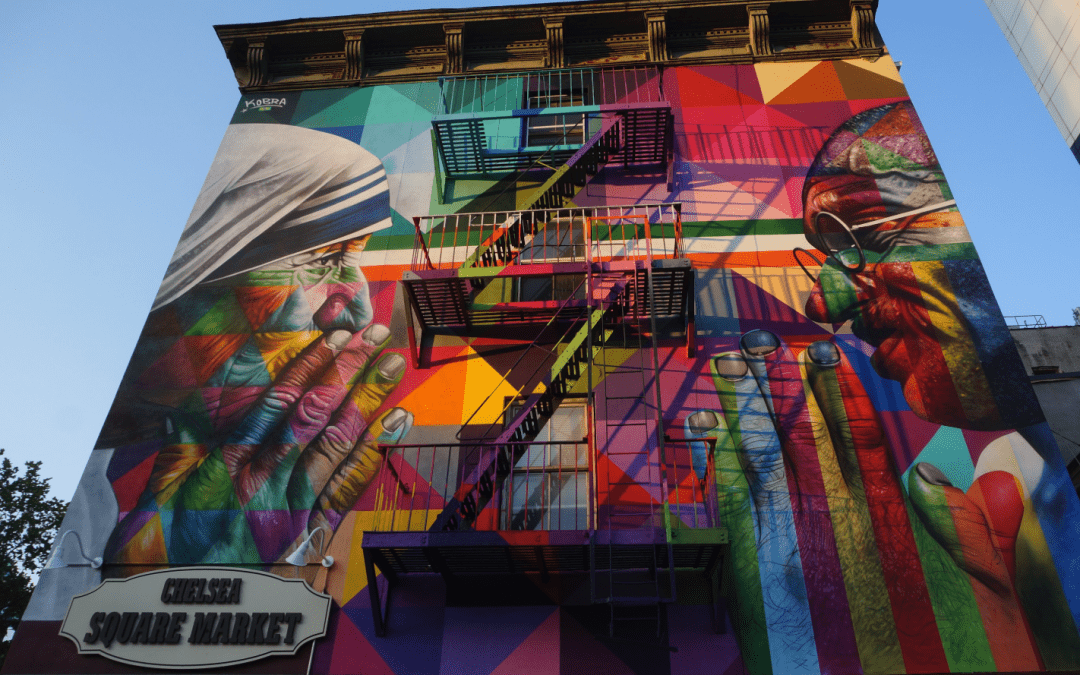

To “Be the change you want to see” is a neat slogan, and whether or not Gandhi said it, I am sure he would have been aware of the sacrifices that it suggests that “you” make. Gandhi did not ask the world to do something that he had not already done himself. Gandhi had a cause that was larger than himself. It’s easy to tick off a list of historical figures who have followed his example and shared his core motivation, empathy. Last Friday while shoppers were frantically searching for bargains, my wife, youngest son, and I were walking the High Line Trail on the West Side of lower Manhattan. Along the way I noticed a huge mural on the side of a building picturing Mother Teresa and Gandhi. I learned later that it is a recent addition to the sites of the city and painted by the well known Brazilian muralist, Eduardo Kobra, as an image of “two of the most selfless souls the world has ever known.” Most of us will never approach “selfless” but we are capable of empathy at least some of the time.

While reading my Sunday paper I noticed an op ed written by a local fellow from Strafford, Vermont, Jonathan Stableford, who is a very literate runner as is evident from what he wrote. His piece, “Faulkner Weather, And The Kind of Truth We See,” reminded me that over the last two years we have been exposed to what a total lack of empathy looks like. Deep into his article which uses Faulkner’s story of the post Civil War South, The Bear, as “the hook,” he makes some important points. I have bolded the core message:

The moral challenges our nation faces today are no less complicated than the post-war South. I am not just thinking of the midterm elections …, but of the larger question of what it means to be a citizen in this country, this continent, this world and this universe.

I have learned some sobering things in my seven decades: that we will never stop fighting wars or destroying the planet; that there is no such thing as a lasting peace; that human beings will kill one another whether in depravity or greed or self-defense or for some notion of justice, and then struggle to explain or justify the meanings of these terms; that we will never eliminate poverty or hunger or treat every citizen fairly; and that we will continue to bring sweet children into the world, knowing that one day they too will become disillusioned.

Realizations like this should bring a person to despair, but that’s not the case for me because in literature I find hope. Camus, for example, recasts Sisyphus as an existential hero for the way he thinks as he trudges down the hill to retrieve his stone.

We are at a time in American history where we need to hold onto a few truths that might save us: Empathy is holier than pride, political beliefs must be open to reasonable challenge, compromise is not automatically a sign of weakness, and choosing between science and the arts is a false dichotomy.

There are other truths, but my point is that most people already agree with them although their behavior sometimes suggests they do not. Who, for instance, doesn’t understand that in a functioning family compromise is essential? Who, trying to assemble a wheelbarrow from parts in a box, doesn’t want instructions from someone who has already completed the task? And who doesn’t know that children have a natural appetite for songs?

“Fine,” the skeptic says, “but these are platitudes. The real question is what are we to do to heal the discord in the country and to solve problems like income inequality? What are we to do about the refugee situation?”

Mr.Stableford answers the “skeptic’s” question by going back to Faulkner’s story and its hero, Isaac:

What he [Isaac] becomes may be no model for a nation in trouble, but his heroic pursuit of the truth is. No one wants to end up like the heroes of most literature (think Hamlet or Mrs. Dalloway) but we recognize our own struggles in theirs, and we emerge from reading about them or seeing them on stage a little wiser.

Near the end of my run I felt something like hope. Perhaps it was the endorphins or the promise of breakfast, but there was something else as well. At this time of year the leaves have fallen and the land reveals itself clearly, almost like a confession. Ridge lines, invisible for months through the glory of foliage suddenly jump into focus, and outcrops and boulders as well, some of them fuzzed with vibrant moss.

It’s a kind of truth we see at this time of year, and with truth come some possibilities.

I hope that it is obvious that I am going to suggest that if you are interested in living in a better world or country or seeing some progress because you care, it is going to require you to exercise hope and empathy. Skeptics see an exercise of empathy to be at variance with the pursuit of one’s best interest. The Triple Aim is probably a long shot in your lifetime, but if its ideals call to you, then your hope lies in casting your vote along with others who are empathetic dreamers willing to pursue a world that will cost them something in the moment. Change always takes energy and exacts a price from those who respond to the “weakness” of caring about the problems of others.

For me the most remarkable of many stories about President Obama that Michelle Obama told in her book, Becoming, describes something that happened very early in their relationship. She was asleep on a mattress in his very hot sublet apartment when she awoke to find him staring at the ceiling deep in thought. Here are her words:

In those days, Fifty Third Street was a hub of late night activity, a thoroughfare for cruising lowriders with unmuffled tailpipes. Almost hourly, it seemed, a police siren would blare outside the window or someone would start shouting, unloading a stream of outrage and profanity that would startle me awake on the mattress. If I found it unsettling, Barack did not. I sensed already that he was more at home with the unruliness of the world than I was, more willing to let it all in without distress. I woke one night to find him staring at the ceiling, his profile lit by the glow of streetlights outside. He looked vaguely troubled, as if he were pondering something deeply personal. Was it our relationship? The loss of his father?

“Hey, what’re you thinking about over there?” I whispered.

He turned to look at me, his smile a little sheepish. “Oh,” he said. “I was just thinking about income inequality.”

This, I was learning, was how Barak’s mind worked. He got himself fixated on big and abstract issues, fueled by some crazy sense that he might be able to do something about them. It was new to me…

It was the summer of 1989. George H. W. Bush was president. Obama still had two years to go at Harvard Law School. It would be twenty years before he became president, but he could not sleep because he was thinking about economic inequality.

I have been thinking that Michelle Obama’s description, “He got himself fixated on big and abstract issues, fueled by some crazy sense that he might be able to do something about them” could be applied to Don Berwick who like Obama, Gandhi, and Mother Teresa has always had an outsized hope and a plan to make a difference as one person being an example and inspiration for others. I know that about the same time Obama could not sleep Don Berwick was beginning to think about how to improve healthcare. He knew that we were not doing enough to improve quality. It would be more than a decade before we would know that quality care is care that is equitable as well as patient centered, safe, efficient, effective, and timely. Empathy, if it is real, is a call to action and often a call for a plan. To have empathy, concern, hope for a change and do nothing is pretty useless.

Don Berwick remains empathetic. I think his empathy is bidirectional or all-encompassing. He cares about patients and he cares about those who help deliver care. He is still trying to gain “votes” for his concern. Recently to try to help us understand what we can do and to emphasize the need to be effectively involved in the effort to achieve the Triple Aim he produced a little YouTube clip, “Why Healthcare Policy Matters.”

The clip is less than three minutes long and deserves your attention. Don has always said that our concern begins with the patient. He then shows how “micro systems” link our individual efforts to the macrosystems within which we work. Finally, he makes the leap to healthcare policy and reasons that it is at the policy level that our “degrees of freedom” to create change occur. If we care, we will try to be involved at each of the four levels presented from the bottom up. His suggestion is that for the TripleAim our empathy and involvement must go all the way up to the policy level.

Four Tiers of Care Improvement

4) Health care policy and environment

3) Macrosystems: healthcare organizations and leadership

2) Microsystems: Working with other providers, processes

1) Interaction and encounters with patients.

Top down, bottom up, or in between. Wherever you work, you can make more of a difference if your interest and concern is felt all the way to the top. Your vote counts. None of the theory works without the collective concern or empathy of many of us. Empathy without effort makes no difference, and the efforts are supported by an understanding of why policy makes a difference, and how we can make a difference in setting policy. These are good things to think about as we consider how the recent gains in the midterm elections can be used to build toward a better day.