May 15, 2020

Dear Interested Readers,

The Challenge: Restart the Economy Without Inducing a Resurgence of COVID-19, and Other Musings

I will begin with the “Other Musings” part of what I want to write to you:

Somewhere, from someone, I recently heard that each day of the last two months has been like “Groundhog Day,” deja vu, all over again. The reference was to the 1993 movie starring Bill Murray, not to the celebration on February 2. I must admit that I enjoyed the movie, but I did not catch the deeper meaning that others saw in it. In 2006, on the evening before Groundhog Day, I was out for a run and was listening Christopher Lydon who had an excellent talk show on public radio. I was surprised to hear him talking about a person that I knew, Stanley Cavell, who was an Emerson scholar and professor of philosophy at Harvard. Boston is a small town and the academic/medical community is even smaller. Living in the Boston area for over fifty years, I met many remarkable people and this was not the first time I had heard a prominent acquaintance mentioned on local radio.

I knew Professor Cavell as an Emerson scholar. I learned from the interview that his writing included philosophical reflections on culture, especially the movies. To my further surprise I learned that he had gained some notoriety from an article in the New York Times in1996 where he identified Groundhog Day as one of the most important films of the century. The exact quote which I have lifted from another article is:

A small film that lives off its wits and tells a deeply wonderful story of love. It creates a vision of the question I ask here — of what will endure. Its vision is to ask how, surrounded by conventions we do not exactly believe in, we sometimes find it in ourselves to enter into what Emerson thought of as a new day.

Professor Cavell discovered that connecting Emerson to Harold Ramis and Bill Murray seemed like a stretch to some people, and required more explanation, but his idea generated a lot of reflection. Most of us are not philosophers, and “like Groundhog Day” has just become a new way to name the repetitive patterns or monotony of our lives. Dr. Cavell saw even more in Groundhog Day than another way to imply “deja vu.”

Stretching the ideas offered in the movie in an attempt to add meaning to the frustrations of the last two months may seem crazy, and at best, hard to understand. But, the comment I heard made sense to me at a level that was deeper than the monotony we are all experiencing. With Professor Cavell’s help, I can see more in the movie, and more in the experience that we are going through than just the humor of “Groundhog Day” or a new way of saying “deja vu.”

Professor Cavell saw that Murray’s character got out of the cycle of sameness through a process of transformation. He went from being a self centered, rather narcissistic, TV weatherman to a person capable of a loving relationship and someone who saw value in being part of a community. Emerson’s friend Thoreau told us that there was a lot to learn by the closer examination of what is near us. He observed:

“I have traveled a good deal in Concord; and everywhere, in shops, and offices, and fields, the inhabitants have appeared to me to be doing penance in a thousand remarkable ways.”

Like Thoreau, I think that we can discover a lot about the work we need to do by observing the moment and reflecting on what got us here. Perhaps the combination of our medical and economic losses are a form of collective penance for our previous lack of attention to what is most important, being sure that everyone has an equal opportunity in life, and in health.

I would direct your attention to a fabulous conversation between Ezra Klein of Vox and David Williams of the Harvard University T.S. Chan School of Public Health. I have bolded a few phrases in an edited version of the introduction where Klein writes:

In Michigan, African Americans represent 14 percent of the population, 33 percent of infections, and 40 percent of deaths. In Mississippi they represent 38 percent of the population, 56 percent of infections, and 66 percent of deaths. In Georgia they represent 16 percent of the population, 31 percent of infections, and just over 50 percent of deaths. The list goes on and on: Across the board, African Americans are more likely to be infected by Covid-19 and far more likely to die from it.

This doesn’t reflect a property of the virus. It reflects a property of our society. Understanding why the coronavirus is brutalizing black America means understanding the health inequalities that predate it…

At the center of Williams’s work is an attempt to grapple with some of the most difficult and sensitive questions in public: Why do black Americans have higher rates of chronic illness, disease, and mortality than white Americans? Why do those disparities remain even when you control for variables like income and education?

…In this conversation, Williams doesn’t just give the clearest account I’ve heard of the coronavirus’s unequal toll. He also gives the clearest account of how America’s institutional and social structures have led to the most profound and consequential inequality of all.

During the conversation Dr. Williams points out that the health issues of black Americans have been well documented for more than a hundred years. He gives us a quote from the 1890s by W. E. B. Du Bois.

When we emerge from our Groundhog Day monotony of hearing every day the same assertions of blame for lack of insight and managerial malfeasance, countered by complaints of conspiracy and the imaginary efforts of the purveyors of “fake news,” we will be faced by the same problems that we were ignoring when this bad dream of Groundhog Days began. The question will not just be, “What did we learn?” The real question will be, “What will we change based on what we have learned.” I think that if we learn what Bill Murray’s character learned, that we must focus on a transformation that involves love and community, then perhaps we will avoid a continuing downward spin.

But, we are not at the moment when we begin again. We are still engaged in getting out of a depressing process which many would deny or would like to see magically disappear. It is remarkable that so many people have been willing to make the personal sacrifices that at most have “cut our losses.” I agree with the critics of the president who say that it did not have to be this bad. I also agree with the president when he says it could have been worse. The fact that it has not been worse is attributable to the noble and courageous actions of healthcare workers, the selfless sacrifices of “essential workers,” many examples of remarkable leadership at the state and local levels of government, and some outspoken contradictory voices from within the federal government that have compensated for the president’s deficiencies and inconsistencies. What has happened is behind us. What is before us now is a choice between a calculated logical path forward complete with exit ramps and fail safe options or a headlong charge toward “getting back to normal” born of fear and boredom. I have read some experts query whether or not the president has opted for a surreptitious path to “herd immunity.”

A recent article in the Atlantic by Yascha Mounk paints a dismal vision of the future that is grounded in facts, history, and a knowledge of our national character and attitudes.

…the chances of finding a transformative treatment against COVID-19 that could be deployed very soon have dwindled considerably.

We won’t get to herd immunity in the near future. A miracle drug is not in sight. The only way to restart the economy, then, is to put a highly effective system in place to test millions of people, trace their movements, and quickly quarantine those who might have been infected.

But even as the past few days have brought bad news about the science of the pandemic, they have brought terrifying news about its politics: It now seems less likely than ever that the United States will do what is necessary to reopen the economy without causing a second wave of deadly infections.

Our challenge is to improve on that prediction. Utilizing science and a more enlightened view of the experience in past pandemics is a choice that is difficult for us to make because of our culture of “states’ rights, individual freedom, and the skepticism of many Americans about opinions coming from experts. These tendencies are magnified by the inconsistencies in messaging coming from our president.

George Santayana advised us that “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”That quote must certainly have been what Terry Gross had in mind when she invited John Barry, author of the 2004 book, The Great Influenza, to her show, “Fresh Air.” His book is back on the best seller list for good reason. The largest losses from the 1918 epidemic occurred in the “second wave” of the pandemic. It is also interesting to note that Woodrow Wilson was very ill with the virus during the negotiations that led to the Treaty of Versailles. Berry points out that difficulties concentrating were a symptom of the Spanish Flu and that Wilson “caved” on most of his points for a “blameless treaty” which led to a horrible treaty that contributed to the rise of Hitler and World War II.

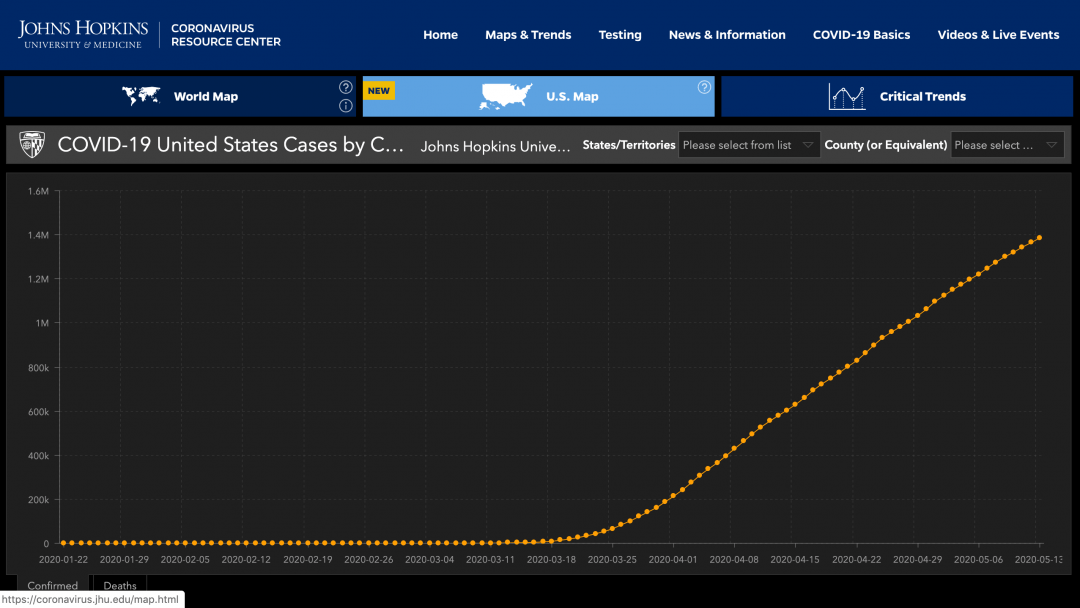

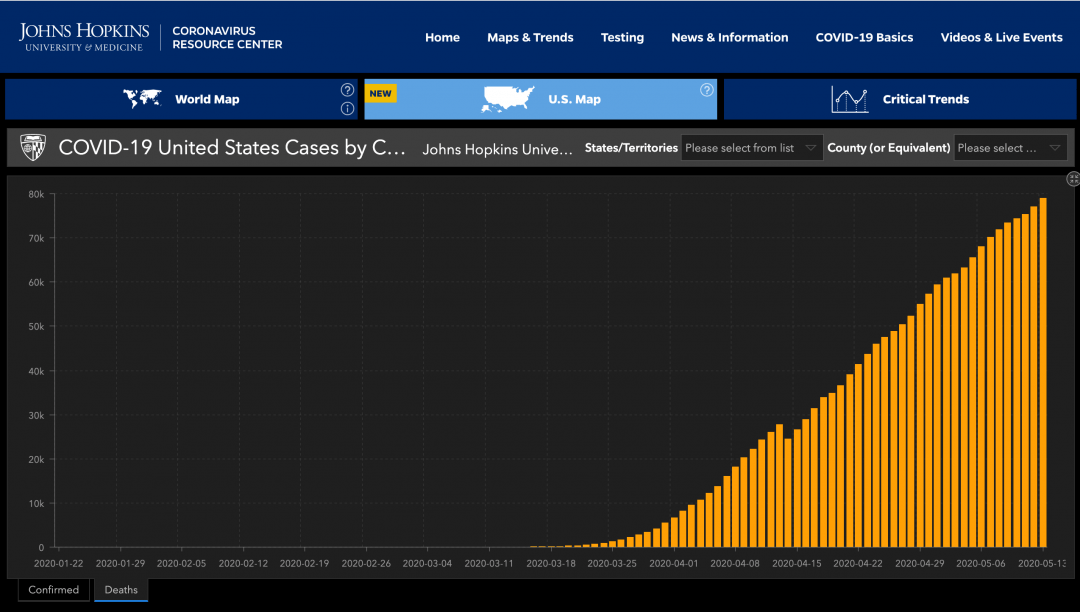

I have great concern about the continued increase in unemployment. We now have more than 36 million people getting unemployment benefits. I am more concerned about what the data suggests is our lack of control of the virus despite what we have been doing. I offer you screen shots of the graphs showing the trajectory of cases and deaths since the pandemic hit our shores. Remember, there is good evidence that the numbers for both cases and deaths represent underreporting. The data comes from the Johns Hopkins reports. It is hard to look at the slope of these lines and be optimistic about what is likely to happen as we attempt to move away from confinement toward business as usual. We want it to be over, but the charts show that we have not done much to change the slope of the lines in ways that show that we have the virus under control. We must be happy with the partial success of knowing that without what has been sacrificed the lines would have a steeper slope.

Our attention at this moment must be on how to make careful attempts to come out of confinement that are driven by personal choices informed by experts and leaders who are not basing their pronouncements on the president’s need for the economy to improve as a path to his re election. Atul Gawande has given us a thoughtful article in the online version of the New Yorker this week. The article is entitled “Amid the Coronavirus Crisis, a Regimen for Reëntry: Health-care workers have been on the job throughout the pandemic.What can they teach us about the safest way to lift a lockdown?” It’s a long title, but the piece is filled with advice based on data, history, and his experience working at Mass General/Brigham formally Partners Healthcare. As always, I am impressed with his ability to teach us with a combination of history, current observations, facts, and analysis.

He begins:

In places around the world, lockdowns are lifting to various degrees—often prematurely. Experts have identified a few indicators that must be met to begin opening nonessential businesses safely: rates of new cases should be low and falling for at least two weeks; hospitals should be able to treat all coronavirus patients in need; and there should be a capacity to test everyone with symptoms. But then what? What are the rules for reëntry? Is there any place that has figured out a way to open and have employees work safely, with each other and with their customers?

It is a good question that he quickly answers:

Well, yes: in health care. The Boston area has been a COVID-19 hotspot. Yet the staff members of my hospital system here, Mass General Brigham, have been at work throughout the pandemic. We have seventy-five thousand employees—more people than in seventy-five per cent of U.S. counties. In April, two-thirds of us were working on site. Yet we’ve had few workplace transmissions. Not zero: we’ve been on a learning curve, to be sure, and we have no way to stop our health-care workers from getting infected in the community. But, in the face of enormous risks, American hospitals have learned how to avoid becoming sites of spread. When the time is right to lighten up on the lockdown and bring people back to work, there are wider lessons to be learned from places that never locked down in the first place.

He gives us some basic rules with supporting data. I will let you read the case he makes for each rule. You know the basic points:

- Start with hygiene. People have learned that cleaning your hands is essential to stopping the transfer of infectious droplets from surfaces to your nose, mouth, and eyes.

- Disinfecting surfaces helps, too, and frequency probably matters…The key, it seems, is washing or sanitizing your hands every time you go into and out of a group environment, and every couple of hours while you’re in it, plus disinfecting high-touch surfaces at least daily.

- We have all now learned the six-foot rule for preventing transmission of contagion-containing droplets...The six-foot rule isn’t some kind of infectious-disease law, however. There’s no stop sign at six feet that respiratory droplets obey.

He offers substantial information about the relative infectious characteristics of the virus.

COVID-19 isn’t actually crazy infectious. Measles is crazy infectious… By comparison, a person with covid-19 will infect, on average, only two to three others out of all the people he or she encounters while going about ordinary life. Exposure time matters: we don’t know exactly how long is too long, but less than fifteen minutes spent in the company of an infected person makes spread unlikely…The six-foot rule goes a long way to shutting down this risk. But there are clearly circumstances where that is not sufficient. At the right point in the illness, under the right environmental and social conditions, one person can produce a disaster.

The delay in initiating the shut down, inadequate PPE, a shortage of ventilators, and inadequate testing are the reasons we have over a million cases with over 80,000 deaths. Throw in the disadvantages of the populations that do essential work and suffer inequities in food, housing, and medical care and we can explain much of what we have seen. Going forward, our ability to ramp up testing will be a large factor in managing without a second wave of concern until we have a vaccine or effective management. Atul says it better:

Testing when people have symptoms is important; with a positive result, a case can be quickly identified, and close contacts at work and at home can be notified. And, with a negative result, people can quickly get back to work …Tests for people with symptoms are becoming increasingly available…self-screening is obviously far from foolproof…Even the most scrupulous check-ins, however, can do only so much in this pandemic, because the sars-CoV-2 virus can make people infectious before they develop symptoms of illness. Studies now consistently indicate that infectivity starts before symptoms do, that it peaks right around the day that they start, and that it declines substantially by five days or so.

He continues his logical analysis:

That’s why we combined distancing with masks. They provide “source control”—blocking the spread of respiratory droplets from a person with active, but perhaps unrecognized, infection.

He explains why the N95 type masks are better but…

Don’t ditch your T-shirt mask, though. A recent, extensive review of the research from an international consortium of scientists suggests that if at least sixty per cent of the population wore masks that were just sixty-per-cent effective in blocking viral transmission—which a well-fitting, two-layer cotton mask is—the epidemic could be stopped. The more effective the mask, the bigger the impact…They are designed to safeguard others, not the wearer. The basic logic is: I protect you; you protect me…Evidence of the benefits of mandatory masks is now overwhelming.

He does hold the administration accountable:

Domestic production of masks in the U.S. has been delayed by inadequate federal support and coördination, but it is nonetheless ramping up.

His summary of actions and a concern:

The four pillars of our strategy—hygiene, distancing, screening, and masks—will not return us to normal life, but, when signs indicate that the virus is under control, they could get people out of their homes and moving again….I have come to realize that there is a fifth element to success: culture. It’s one thing to know what we should be doing; it’s another to do it, rigorously and thoroughly…

Culture is the fifth, and arguably the most difficult, pillar of a new combination therapy to stop the coronavirus. People tend to focus on two desires: safety and freedom; keep me safe and leave me alone…It’s about wanting, among other things, never to be the one to make someone else sick.

He is a realist:

The combination therapy isn’t easy. It requires an attention to detail that simply staying in lockdown does not. But, during the crisis, people everywhere have shown an astonishing capacity to learn from others’ successes and failures and to rapidly change in response. There is still much more to learn, such as whether we can safely work at less than six feet apart if everyone has masks on (the way nurses and patients do with one another) and for how long. But answers will come only through commitment to abiding by new norms and measuring results, not through wishful thinking.

Leadership is key:

As political leaders push to reopen businesses and schools, they are beginning to talk about the tools that have kept health-care workers safe. The science says that these tools can work. But it’s worrying how little officials are discussing what it takes to deliver them as a whole package and monitor their effectiveness… [When Georgia reopened]The government had no formal plan for surveillance testing to look for early signs of failure. Many leaders didn’t even seem interested. President Trump has sought to compel meatpacking plants to stay open, even though thousands of workers have been infected by COVID-19. He has encouraged protesters to flout public-health guidelines, and seems to consider it embarrassing to set the example of wearing a mask—even as the virus became the country’s top cause of weekly deaths in mid-April and then penetrated the White House. This is about as far as you can get from instilling the culture of the operating room.

It seems to be up to us. Gawande believes in the good sense that you and I have:

Still, regardless of what model politicians set, more and more people are figuring out how to do what has worked in health care, embracing new norms just as we accepted social distancing. We see proof of a changing culture every time we step out and find a neighbor in a mask. Or when we spend time to make our own fit better. Or when we’re asked whether we have any concerning symptoms today. Or when we check to see whether the number of COVID-19 cases in our community has dropped low enough to warrant reëntry. If we stick to our combination of precautions—while remaining alert to their limitations—it will.

I hope that he is right. I doubt that the president even knows who Woodrow Wilson was. Dr. Bright and Dr. Fauci are hanging a lot of crepes.

Social Distancing on the Trail

I am lucky. I can avoid all crowds. It is obvious from looking at where there are the most COVID-19 cases, being indoors in a crowd is dangerous. It would be a good strategy to avoid crowded places like nursing homes, cruise ships, medical conferences, subways, prisons, and crowded beaches. It makes little sense to go out to a crowded bar, or perhaps ride on a packed elevator. Almost anywhere in an urban area is a more likely place to acquire an infection with the virus than in the busiest places where I go in my little town. There is always the possibility that I might come in close contact with an asymptomatic but infected individual, and catch the virus at the post office or the grocery store, but I like my chances. I feel very protected from the virus when I am walking on a trail in the New Hampshire woods.

Despite the fact that the risk on our trails is low, it is not zero. On a nice weekend the best trails in the woods of New Hampshire can get crowded. Parking lots at trailheads can be full and overflowing. The trail up Mount Monadnock or Mount Kearsarge can be like walking on the sidewalk in Manhattan. Folks and their dogs abound. Last Sunday, my youngest son and I convinced my wife to join us on a walk up the Great Brook trail near Pleasant Lake. The picture in today’s header was taken by my wife on the hike. You can tell by the huge stone wall that there was a time when people lived and worked along Great Brook. The water in Great Brook flows from a beaver pond two miles away called “Devil’s Half Acre Pond,” and eventually ends up in the Merrimack River near Concord. There are beautiful cascades near the pond which we did not reach on the Sunday walk.

I was impressed that most of the people we encountered were practicing social distancing and many were wearing masks. That was pretty good for the “Live Free or Die State.” Always remember that “freedom” includes the right to exercise good judgment, reject hoaxes, accept the protective benefits of science, and go for a walk whenever you can.

When I am in the woods, or just enjoying the lake in my kayak, I know that I would not give up those pleasures by losing the bet on a test of luck associated with a haircut, a trip to the movies, or a dinner at a restaurant. If you feel an intense need to go to a mall in the near future, I hope that you will pass on it in favor of a good walk in a park or wooded area near you.

Be well! Practice social distancing. Wash your hands frequently. Don’t touch your face. Cover your cough. Stay home unless you are an essential provider. Follow the advice of our experts. Assist your neighbor when there is a need you can meet. Demand leadership that is thoughtful, truthful, capable, and inclusive. Let me hear from you often, and don’t let anything keep you from doing the good that you can do every day,

Gene

Eve,

I share your concern. I think that your example is instructive. There is a lot of work in the transition from policy to practice. I liked the explanation that Gawande gave about the benefit of masks that are not N95s. Your mask gives me some protection, and my mask gives you some protection.

Your concerns about access to hand sanitizer are correct. I would advise the practice to have the receptionist make sure that hand sanitizer is available at the desk and at several places in the waiting area. Her area should be wiped after each patient. I would also hope that the schedule is managed so that no one spends any time waiting. In Lean thinking waiting rooms are evidence of an opportunity for systems improvement. In COVID-19 terms they could be considered hot spots for potential infection.

Thanks for this excellent comment. I think that we are on a learning curve and that sharing experiences of concern promotes everyone’s learning.

Be well,

Gene

Dear Gene,

Thank you for all of this, which I will be sharing with family and friends. I had an interesting interaction today that I want to share with you: I went to the ophthalmologist today for the first time since November. My March appointment was cancelled so I was able to schedule an appointment today. I was nervous. What would the facility be like, and was I entering a danger zone?

Someone at the front entrance asked me questions about my health and how I was feeling, whether I’d been in contact with anyone with Covid-19, etc. Fine. I went upstairs to the receptionist and was asked to stand 6 feet away when checking in. Fine.

But when I inserted my card to pay the copay, there was no hand sanitizer that I could see on the counter. Anywhere. I asked the receptionist about it, and she said, “We sanitize daily.” I was stunned because, as I understand it, daily is insufficient. I asked again. She answered again in the same way.

Finally, I said, “If someone has touched this machine before me, I need to use hand sanitizer.” She finally told me where the sanitizer was (imagine her rolling her eyes, although I didn’t look at her to verify), and it was way off in the corner, on a chair, where nobody would have seen it. When I thanked her she said, in a patronizing way, “Let me make this easier for you,” and put the sanitizer on a coffee table. Where it should have been all along, as well as on the counter right next to the credit card reader. I was appalled.

The rest of my visit was good, with everyone wearing masks. It is not possible to keep socially distant when having an eye exam, although we all wore masks. So do masks protect against Covid-19 when all parties are close together? I hope so. What I remember most about this visit is the receptionist telling me, essentially, that I didn’t need to use hand sanitizer because they clean their surfaces “daily.” This is probably the most well-known, well respected integrated health system in the country. Unbelivable.

I was surprised. I was shaken. I care deeply about the health and well-being of healthcare professionals and I care just as deeply about the health and well-being of patients. I didn’t tell anyone about this exchange–and clearly it was not a teachable moment for the receptionist–but it is a reminder about how much better every single person in healthcare matters and still needs to do. I am a champion up to a point. Today I remain a somewhat frightened patient.

Thanks, as always,my friend, for your wisdom, insight, and lessons,

Eve