March 10, 2023

Dear Interested Readers,

Musing About How Things Have Changed and Hopefully Will Continue To Change

My wife and I have just returned from a trip to my mother’s hometown in North Carolina where I spent many happy summer days as a child. Our trip had a purpose. March 3rd would have been my mother’s 104th birthday. She died in early January 2013 less than two months short of her 94th birthday after many years of coronary disease, painful arthritis, and poorly managed chronic bowel disease that was eventually diagnosed as Crohn’s Disease-regional enteritis.

My dad died in 2018 about two months short of his 98th birthday. In 1985 my father built a small office building in Lincolnton in a doctor’s park next to the county hospital. He had spent three years becoming a licensed pastoral counselor as he approached retirement in the early 80s. After his retirement, my parents moved back to Lincolnton to live in my mother’s girlhood home. Dad was the only licensed mental health professional in Lincoln County at the time and had become so busy with referrals from local PCPs and the court system that he decided he needed an office near the hospital.

My dad was a minister with a broad range of interests. He was a good businessman who had been traumatized as a child during the depression, and as a result of having been very poor, he invested in real estate, held mortgages from people who could not qualify for loans from banks, and lived a very frugal lifestyle. He rented out half of his office building to a local urologist. He always thought the little office building was his best idea and referred to it as his “goldmine.” Eventually, he rented the whole building to the urologist when he and my mother moved to the northern Atlanta suburbs to be closer to my youngest sister and the tertiary medical care my mother needed. After my mother’s death, my dad moved back to Lincolnton and remarried.

Lincoln County Hospital was not that old. It opened in 1969 to replace a very small hospital that had been opened in a large home that was more like an infirmary. In 2000, Carolinas Health began to manage the hospital and in 2010, Carolinas, now Atrium Health, closed the old hospital and opened a new $90 million dollar 101-bed facility on a 65-acre campus with an associated 40,000-square-foot medical office building. Most of the doctors in town became employees.

Dad was lucky since the urologist who rented from him was one of the few doctors who did not join Atrium Health or was not recruited. Dad continued to collect rent until the urologist retired which was about the time Dad died. Having Atrium (nee Carolina Health) take over healthcare is hardly the only change in Lincolnton since my childhood or since 1985 when Dad built his building. Atrium is now building a new urgent care facility on the other side of town. There are Atrium mental health offices, rehab facilities, specialty centers, and management offices scattered around town. Healthcare which is almost synonymous with Atrium Health is now the third-largest employer in the county. 11% of those employed in Lincoln County, about 4,000 people, work in healthcare, and most of them work for Atrium.

Even before 1985, things were changing. The mills that employed so many of the residents in the county were closing and being replaced by other forms of manufacturing and huge trucking facilities. Lincolnton has a geographic advantage, and because of its proximity to Charlotte, it has been in a transition that seems to have made it more prosperous.

When Atrium opened the new hospital that replaced the old Lincoln Medical Center, Dad’s building became virtually unsellable. The good news for me and my sibs was that the building cost less to maintain than a storage locker and for convenience after my father died, we moved most of the family heirlooms, my father’s journals, my mother’s extensive genealogical writings, and charts, tons of family pictures, and all the things a couple collects over seventy years of marriage into the empty office building.

Things changed again when the county decided to convert the old empty hospital into offices and build a new courthouse next to it. Now, Dad’s building has a new value perhaps as a law office, but it needed to be emptied before we could put it on the market. My brother lives in Lincolnton and my two sisters live in Georgia. We decided to gather on Mom’s birthday and spend a few days cleaning out the building and making the decisions about what to keep and what to discard or donate that we should have made four years ago. My wife and I decided to drive to North Carolina so that I could bring the items that had the greatest sentimental value for me back in our SUV and not risk damage or loss from shipping. After we had filled our SUV there were many items that we could not give up, and could not carry back with us, and they are being shipped.

I apologize for the long intro, but while I was in Lincolnton, I realized that several of my feelings about the practice of medicine have a connection to Lincolnton and that the story of healthcare in Lincolnton is an example of the transition of medical practice from a “cottage industry” in a small town in a rural environment to being part of a huge medical system. Lincolnton is emblematic of the evolution of healthcare in America.

“Change” has two components, technical and adaptive. “Technical change” like the upgrade in medical technology that Atrium has brought to Lincolnton has a learning curve but is usually welcome, obviously beneficial, and usually pretty easy. The hardest part of change is “adaptive change.” Adaptive change is hard because it involves the emotional work of letting go of what has been known and has been comfortable and trusting that what is coming could be worth the stress of the move. Many things that once had value, like much of what was stored in my dad’s old office are hard to discard but have no place in the world going forward. Adaptive change is about dealing with loss, uncertainty about the future, and ambiguity about what still has value, and what will be needed in the future.

Everything that has happened to healthcare in Lincolnton has not made healthcare more patient-centric, and it certainly has not reduced the cost of care, but it is the way things are. Change seems to be like a tsunami that sweeps away what was and leaves you no option but to accept what “is” and make the best of it. There is no going back, but as is true with my family’s artifacts, we must decide what we should try to preserve.

I can vaguely remember going to see my doctor for “shots” before 1953. I reference 1953 because that is when my grandfather had a very large myocardial infarction at age 64. Before his event, he walked a mile every morning to work at the train station where he was the freight agent, walked home for lunch, and then walked back to work for the afternoon before walking home at the end of the day. Within his walking range were the church, the post office, the courthouse, the bank, clothing stores, and the grocery store. My grandparents never owned a car. As an employee of the Seaboard Railroad, he and my grandmother could take the train for free whenever they needed to travel. A car was not a necessity.

Perhaps because he was constantly smoking his pipe, walking over four miles a day for four decades did not protect him from a cardiac event. I don’t know about his family’s history of heart disease before him, but his son, my uncle, had his first CABG about the same age his dad had his MI, and several re-ops before having an early version of an implantable defibrillator and eventually dying with chronic CHF. My mother was a non-smoker who was always hypertensive, had an elevated cholesterol, and needed an angioplasty and stent of her mid-LAD in her early 80s despite always taking meds for her hypertension, and beginning statins as soon as they were available. Ditto for me. Mom lived the last twelve years of her with slow AF and a pacemaker to prevent syncope. My hedge against the family disease has been to vigorously exercise all my life, take blood pressure meds since my late teens (I was 4F during the Vietnam era because of an elevated BP), statins for decades, and like my mother, never smoking.

My grandfather was bed-to-chair with multiple episodes of pulmonary edema over the last six weeks of his life, and then he probably had another event that ended his life. He was buried on my eighth birthday in 1953. My grandfather was born too soon to benefit from all the cardiac advancements that have evolved since I went to medical school, but I think my sense of what practice should be like had some connection to his experience. He would have definitely lived longer if he could have had the advantages offered by Atrium Health.

In retrospect, what my grandfather did have that he might not have today was patient-centric care. His doctor, a young fellow who had known my grandparents since childhood lived two doors down from him, and he made many visits to his bedside during his final days. The same man remained the family doctor throughout his career, and then my parents’ care was transferred to his son who took over his father’s practice. Once Carolina Health took over the Lincoln County Hospital, the son like most of the other doctors in the community, became an employee of Atrium. He is now my brother’s PCP. Small-town healthcare has been traditionally interwoven with every other aspect of community life. Everyone is known. The anonymity of city life does not exist. Professional and personal values are a matter of commonly shared knowledge. The doctor and the patient have encounters in the office and at the hospital, but they also see each other at the grocery store, hardware store, at church, at meetings of civic organizations like the Rotary Club, and even at the funeral home.

Atrium has brought every modern healthcare option to Lincolnton. Their medical record system is Epic. I have reviewed my father’s and my brother’s medical records at their request on the “My Chart” function. If something needs to be done that is not available at the new hospital the “mother ship” in Charlotte offers very proficient tertiary and quaternary care. The system now has 40 hospitals and 1,400 “delivery sites.” It is also part of Advocate Health the fifth-largest healthcare system in the country. From what I hear, the size and wealth of the system have not insured easy access, patient satisfaction, or low costs.

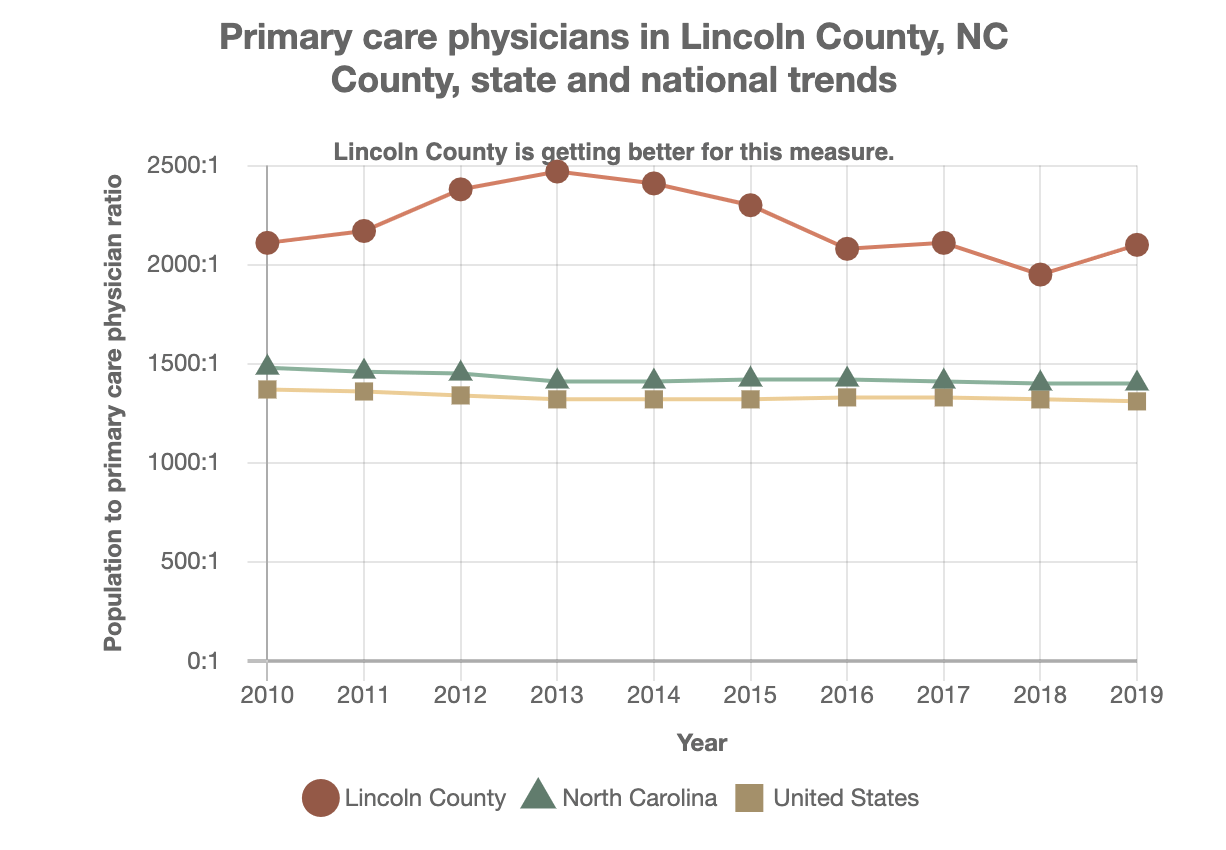

The database from the University of Wisconsin that compares health metrics by county for all counties in the country reveals that Lincoln County has a significant shortage of primary care physicians compared with the rest of North Carolina Counties and the average for the nation.

I hear the same complaints in Lincolnton that I hear almost everywhere I check out systems of care. There are provider shortages, people complain that they watch their doctor’s back as he/she types into a computer, getting attention for an acute problem usually requires going to an urgent care center or EW rather than seeing your PCP who is too busy, and the cost of care is going up. I hear the same complaints in Boston and where I live. Size has much to offer technically, but it seems that it does not necessarily offer an easy care experience.

As I was sorting through boxes and boxes of papers and pictures, I realized that I had had a second “medical experience” in Lincolnton some sixty-six years ago that also stayed with me throughout my career. When I was eleven and my brother was nine, our parents decided that we should have an extended summer visit with our grandmother. My brother had chronic asthma and eczema. I remember my parents chasing him down to give him the allergy injections that the doctor had prescribed. It did not seem fair that he had so many problems when I was fine.

All went well with our visit until we were invited to go swimming at the local VFW facility where there was a very nice pool. Something happened and my brother developed impetigo in his excoriations from his eczema. I remember the weeping encrusted lesions on his arms, legs, and scalp. He was very ill and was appropriately hospitalized at Lincolnton’s little “cottage hospital.” He was in the hospital for several days getting penicillin and having his weeping lesions treated with compresses and washes. Every day I would walk the half mile or so to the hospital which was on the other side of the town square and county court house to spend most of the day with him while watching the nurses attend to him. I was usually present when the doctor came by to check on his progress. He got better quickly, and I think that was when I began to think about becoming a doctor.

When I came to Harvard Medical School in 1967, I did not see myself becoming a medical researcher or academic clinician. Perhaps I was in the wrong place because my goal was to be a very good doctor like the ones I had seen in Lincolnton and the ones in my hometowns who had been easily and comfortably available to me and my family. I also had no interest in “the business” of practice. All of those positions seem quite naive, in retrospect. The final lesson that Lincolnton reveals is that the world has changed. Today, my grandfather might have had the chance to live another decade or two. If my brother was a child today he would get more relief from his asthma and the awful chronic itching from his eczema that made his antecubital and popliteal fossae excoriated bloody messes that were subject to superinfections.

There is no doubt that we have learned a lot and our systems of care can manage problems that could not have been managed before Atrium brought better care to Lincolnton. Indeed, my mother and father left Lincolnton for Atlanta for the care she needed before Carolina/Atrium brought more technically competent care to town. What seems to be missing though in this new world is the sense of concern and care that existed before we became so advanced. Would it not be wonderful if we could have the sense of care that it seems we once had coupled with the technical competence we now enjoy?

I keep remembering what I once heard Atul Gawande say. He said that there was a time when we were limited by what we did not know. It’s harsh to say but compared to today we were ignorant. Ignorant of all the skills and knowledge we have gained over the last fifty years. Now, we are no longer ignorant. Our shortcomings are derivative of our inability to manage systems. Our systems-difficulties have made care a less satisfying experience for those who receive care and for those who deliver it. So, now we are no longer ignorant; we are inept.

I want to end on a hopeful note. Life for most people in Lincolnton is better now than it was sixty years ago when the mills were still running and the doctors could only offer you attention for many of the problems we can now solve. I think we are a work in progress. Perhaps, AI will free up more professional time to give to patients. Perhaps, moving away from a fee-for-service finance system is the answer. Perhaps, the answer is a restructuring of how care is delivered in ways yet to be imagined. I don’t think the change process is over in Lincolnton or anywhere else in the country, so there is hope that someday we will be both informed and efficient.

A Trip To Spring and Back

My wife and I left New Hampshire and headed for North Carolina on February 28th just ahead of the full furry of two back-to-back snow storms that added more than a foot of snow to the residual foot or so of snow that was already on the ground. New London has had a covering of snow since early December despite the fact that most of the days in February were unseasonably warm. During February, we hit sixty at least once, and there were many days in the fifties, and almost all the daytime temps were over forty even though at night it was often in the teens or low twenties. My friend who revels in the process of making maple syrup thought it was a gift to be able to start collecting and boiling sap at least three weeks earlier than usual. We returned home yesterday to more typical late winter weather.

As we slowly headed south along the Connecticut River on Interstate 91 we were dodging snow plows. Snow had turned to freezing rain by the time we got to Connecticut and the precipitation was just plain rain by the time we got to the Hudson River. We finished that first day in bright sunshine in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. It was spring with pleasant temps in the low seventies by the time we reached Lincolnton, North Carolina where I have Swiss-German roots that go back to the late seventeen hundreds. It seemed like every two-hundred-plus miles we traveled south the calendar advanced a week into spring.

In Lincolnton, the deciduous trees were trying on a few bright green leaves. There were white Barlett Pear trees and pink Redbud trees everywhere in yards and even in the wooded areas along the highways. Daffodils and forsythia added bright yellows to the scene. I felt like I had taken a five or six-week trip into the future.

Once we dove into old exam rooms and doctor’s offices that were full of items that you might find at a yard sale, we found that the job of “letting go” was easier than we had anticipated. My sibs and I easily negotiated who would get each item that had emotional or monetary value. I took most of my father’s papers which included his handwritten sermons and years and years of journals that I anticipate will reveal his own struggles with faith. My mother had saved every card or letter ever written to her and had notebooks full of genealogical research that even included “rubbings” from gravestones. She had albums of newspaper clippings and photographs from everywhere she had ever lived that even included her childhood scrapbook which I had never seen. We took those items that had emotional value and then turned the bulk of the disposal work over to the real estate agent.

Turning over most of the clean-up to the agent allowed us to leave sooner than we had planned. The extra time allowed us to take a more leisurely trip home. The last time we drove on the Blue Ridge parkway was in 1989 which was the last time we had driven to the south. Since then we have always flown into Charlotte or Atlanta. Lincolnton is about 35 miles west of the Charlotte airport which in part explains why Lincolnton has become a “bedroom community” for Charlotte. With the bonus of some extra time, we decided to enjoy some of the Blue Ridge Parkway as we drove north back into winter.

Rhododendrons love the shade and the mountain air. I had forgotten that much of the parkway is lined by forests of rhododendrons that are interrupted by beautiful pastures with grazing cows behind split rail fences. Too bad for us that the “rhodies” were not yet in bloom. We should have made the trip next month! What is available no matter when you drive the parkway are the mountain and valley vistas. Today’s header is a good example of what you might see around many turns. Behind some of the rail fences, we saw examples of mountain life from an earlier era like Mabry’s Mill, pictured below, which lies near milepost 176. The Parkway can be like a scenic ride through a museum of American history.

We are back in winter now as you can see in the picture below which was taken from the door onto my deck after I had done enough cleanup to bring in a load of firewood on my cart.

We may get more snow this weekend, but I do know that spring is only a thousand miles to the south and quickly moving toward us. I hope that wherever you are you will have a great weekend enjoying what is left of winter or welcoming spring.

Be well,

Gene