July 8, 2022

Dear Interested Readers,

Reflections on the Long Journey Toward a Greater Appreciation of the Importance of Public Health and Healthcare Equity

I often wonder what is being taught in medical schools these days. My medical school days are more than fifty years in the rear view mirror. As I review my memories, I can honestly say that I can not remember ever having heard a lecture on public health. I also can not remember hearing the phrase, “the social determinants of health” or any other alternative expression of that concept. We never had a lecture about the cost of care, universal access, or healthcare equity. Quality and safety were not discussed; they were assumed to exist. The only problem about race that we were taught was that there were connections between some races and ethnicities and their individual predilections to certain diseases. The only public health question that I can remember on the National Boards that I took in the fourth year of medical school was about how much chlorine needed to be put in a swimming pool to make it safe. I was clueless. I chose “c” since I had the personal strategy of picking “c” whenever I did not have any idea of the correct answer.

Even though we did not consider the social determinants of health, racial barriers to care, or healthcare biases, I well remember traveling along with all the members of my class on a very dark and cold mid-November Saturday morning in the fall of 1967 to attend a sickle cell “clinic” offered to my first-year class. Our weekly “clinic” rotated around the various Harvard hospitals and was meant to connect what we were learning in the classroom to the real world of medicine where there were flesh and blood people who manifested the conditions that were caused by the issues in biochemistry, genetics, and infectious disease that we were studying in the classroom. At that time, the Boston City Hospital had “services” offered by all three Boston medical schools: BU, Harvard, and Tufts. The Boston City Hospital was also the home of Harvard’s ‘Thorndike Lab’, a famous research unit that produced many of the titans of twentieth-century medicine.

I was particularly excited about the prospect of this clinic at the BCH because the presenter was a famous hematologist from The Thorndike Lab who had connected many diseases to their biochemical and genetic origins. For the clinic, the professor introduced us to a distinguished-looking Black man who had come to the event in a suit and tie. I was surprised when the professor addressed him in front of us as “Bobby” and at one time called him “boy” even though he was at least forty years old.

I came from the South where it was common for white men to address even very old Black men as “boy” and also use only their first name, but this was “enlightened” Boston, and I was surprised. The scene was the last thing that I expected from a Boston Brahmin. Being deferential and not realizing that race was an issue even in Boston, I assumed that this world-famous physician and the gentleman who had come to answer questions about living with his condition had a very unique doctor-patient relationship that had developed over many years that put them on a first-name basis.

Not everyone in my class gave the professor a “pass” on his presentation style. It was the sixties and some members of my class were “woke” to issues of race and protested the lack of courtesy and possible racist attitude that the world-famous physician extended to his patient who had volunteered his time to come in and demonstrate his disease to an amphitheater full of future doctors. Even my woke classmates had not yet come to realize the inherent biases in all clinicians nor the realities of healthcare inequities that subject whole groups of people to a second-tier healthcare experience that produces poorer outcomes across the population.

The memory from that November Saturday morning clinic has persisted unchanged for over fifty years. The fact that the image is so vivid and has not been forgotten may be due to the fact that it was about as close as my medical school experience ever got to a presentation of the impact of caste, class, race, or bias in the practice of medicine. It may have been the closest my education brought me to the issues that now concern me most. In retrospect, I assume that our professors thought their charge was to teach us about the molecular origins of disease, infectious diseases, and the management of trauma, and not about the biases, the social origins of medical problems, or how the issues are addressed as public health concerns impact the individual to create human illness and suffering. There was never a reference to the fact that we should give any serious consideration to efforts to alter the social issues or environmental issues that might impact the individual before us in the hospital bed or on the examination table in the office. Our focus was on the problem in our patient at that moment, and we did not give much thought to the social or environmental issues that caused the problem. Addressing those issues was not our concern.

You might counter by asking me about Francis Weld Peabody who was also a famous Boston City physician who was at the Thorndike Lab and gave a famous speech about “The Care of the Patient” that contains the much-quoted line:

“. . . For the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.”

Peabody stressed understanding the environment from which the patient came, and that was a big leap forward in the 1920s that was reflected in our taking of histories and physicals that included a “Social History” as described in the “Little Red Book” that we were given to take on to the wards as our guide when we began to examine patients. In an important part of his presentation about getting to know the environment from which the patient came, Peabody wrote:

Everybody, sick or well, is affected in one way or another, consciously or subconsciously, by the material and spiritual forces that bear on his life, and especially to the sick such forces may act as powerful stimulants or depressants. When the general practitioner goes into the home of a patient, he may know the whole background of the family life from past experience; but even when he comes as a stranger he has every opportunity to find out what manner of man his patient is, and what kind of circumstances make his life. He gets a hint of financial anxiety or of domestic incompatibility; he may find himself confronted by a querulous, exacting, self-centered patient, or by a gentle invalid overawed by a dominating family; and as he appreciates how these circumstances are reacting on the patient he dispenses sympathy, encouragement or discipline.

What is spoken of as a “clinical picture” is not just a photograph of a man sick in bed; it is an impressionistic painting of the patient surrounded by his home, his work, his relations, his friends, his joys, sorrows, hopes and fears. Now, all of this background of sickness which bears so strongly on the symptomatology is liable to be lost sight of in the hospital…

When a patient enters a hospital, one of the first things that commonly happens to him is that he loses his personal identity. He is generally referred to, not as Henry Jones, but as “that case of mitral stenosis in the second bed on the left.” … the trouble is that it leads, more or less directly, to the patient being treated as a case of mitral stenosis, and not as a sick man…

I hope that you will click on the link “Peabody wrote” which will take you to the full text of Peabody’s words. It is a rich discussion that has always inspired me and is a springboard to the concept of patent-centeredness. Ironically, I did my first “history and physical” on a patient named Mr. Hart who was a patient in the open ward in the Peabody Building of the BCH. He was a 55-year-old man who had been brought to the hospital when he developed crushing chest pain while playing poker. I assumed that he was losing a lot of money. He had suffered an inferior wall myocardial infarction.

Even with his emphasis on understanding the environment experienced by the patient, Peabody and his colleagues had not expanded their view from the focus on the patient and his/her individual disease to an understanding of all of the threats that their populations share. They sought to understand how an environment created disease. It doesn’t seem to be true that it ever occurred to them that they might have some responsibility to change the issue that impacted the patient. I fear sometimes that many healthcare professionals still don’t see a personal obligation to manage or correct the public health issues that are a threat to their patients. They see their job as treating what happens because of those issues. The Harvard School of Public Health was next door to the Medical School’s quadrangle of buildings, but most of us did not carry the connection between medicine and public health much further than the fact that they were both on Shattuck Street.

It was a different world that I think has changed. A lack of attention to public health was not the only thing that need to change. Of the original one hundred twenty students that started with me in 1967, the greatest “diversity” in my class was among white men who did go to a prestigious college in the Ivy League or to non-Ivy elite colleges like Amherst or Stanford, versus those few of us from public universities. There were early nods to gender and racial diversity since within our class there were ten women and less than five students who were Asian or African American.

Diversity in the profession as well as a growing understanding of the social determinants of health and the importance of public health to the practice of medicine have experienced a gradual process of improvement. One of my colleagues at HCHP, Doris Bennett, HMS class of 1949, who was a much-loved pediatrician and leader within our practice, was one of the first 12 women admitted to Harvard Medical School in 1945. In 1857, Harriet Hunt was the first woman to apply to HMS back in 1857, but she and three African Americans were denied admission that year. In the interim of 98 years between 1857 and 1945, many other women tried unsuccessfully to be admitted to Harvard Medical School. Changes that improve the opportunities for women and minorities have been notoriously slow in medicine and may be slower than average at Harvard. Nevertheless, many things have changed in the fifty-plus years since the fall of 1967, but I worry that public health is still not adequately taught.

My training prepared me to treat diseases, infections, and traumas as they affected individuals, and not the population. Our curriculum did encourage inquiry and problem solving over rote memory and prescribed solutions. Compared to practice today, in the early seventies, we were in the dawn of attempts to practice preventative medicine and identify the environmental hazards to health. The risk of lead poisoning from paint had been known for decades going back to early in the twentieth century but it was not until 1992 that Congress directed HUD and the EPA to require disclosures. We knew about “black Lung” disease and mesotheliomas related to asbestos long before anything was done to mitigate the risks to those who might be exposed. In retrospect, we seemed content to deal with the aftermath of those toxins in the individual without much attempt to correct the problems that were creating disease. Our failure back then to address the root cause public health issues that created the illness in the individual before us seems like our “too little, too late” responses that we now apply to pandemics, global warming, and gun violence. It takes a long time and many many affected individuals before we see that a public health issue is the root cause of an individual’s declining health. We will treat many individuals before addressing the specific public health concern that brings them to us and could be improved if there was collective action from the medical establishment to limit the number of individuals who will be injured or become sick with an inadequately addressed public health concern. Perhaps, the problem is that in a fee-for-service world we do not know how to generate revenue by addressing public health problems.

Primary physicians did not begin to pay much attention to preventative care until the mid-twentieth century, although one could argue that vaccinations which began in various forms even before Jenner in the mid-eighteenth century were a form of preventative care. It was not until the late sixties when Edward Fries led a couple of large-scale landmark studies within the VA system that we had proof that lowering blood pressure with medications led to decreases in cardiovascular events and strokes. In a long review of the history of hypertension published in Hypertension in 2011 we read:

The landmark Veterans Administration Cooperative Studies, largely designed and supervised by Dr. Edward Freis, provided early clinical trial evidence for the beneficial impact of lowering blood pressure with antihypertensive agents. In a placebo-controlled trial, active drug treatment in patients with diastolic blood pressures 115 to 129 mm Hg resulted in a lower incidence of stroke, aortic dissection, and malignant hypertension within 2 years.40 Follow-up was terminated prematurely in the placebo-treated patients (15.7 versus 20.7 months in controls) because of a higher incidence of terminating events. A subsequent Veterans Administration placebo-controlled trial demonstrated the benefit of antihypertensive drug treatment of patients with diastolic blood pressures 90 to 114 mm Hg, especially patients with diastolic blood pressures ≥105 mm Hg.41 The 2 studies were published in 1967 and 1970, respectively, and the antihypertensive agents in the trials included varying combinations of reserpine, chlorothiazide, hydralazine, and guanethidine.

I will have my seventy-seventh birthday this month. It is possible that without the evidence Freis generated, like my maternal great grandfather and grandfather who died in their 50s and 60s respectively of the complications of their hypertension, I might have been gone fifteen or twenty years ago. I have been on antihypertensive meds since the mid-sixties. By the time I entered medical school my systolic BP was frequently over two hundred, and my diastolic pressure was greater than one hundred and twenty. Even while I was still in college my doctor started treating me with some brutal meds that were hard to take, reserpine first and then guanethidine in combination with diuretics, before Fries’ results were published. In retrospect I was honored to have another “great” from the Thorndike Lab, Dr. Hermann Blumgart manage my blood pressure when I was a medical student. After his retirement as the Physician-in-Chief at the Beth Isreal Hospital in 1962, Dr. Blumgart enjoyed running the medical clinic for students at the medical school. I saw him frequently. All these memories underline the fact that the practice of preventative medicine is a relatively new insight. Applying the principles of public health and population medicine to the care of individuals is even less developed than the application of the principles of preventative care and cancer screening to the management of individuals.

I often wonder what my life would have been like if I had not had my medicine rotation at The Brigham which was the epicenter of Dean Robert Ebert’s experiment in primary care with an emphasis on health and health maintenance. It was not a choice. It was a random assignment. The dean’s office could have just as easily sent me to the MGH, the Beth Isreal, or the Harvard Service at The Boston City Hospital. It was at The Brigham that I encountered Dr. Joe Dorsey who was the young Chief Medical Officer of Harvard Community Health Plan. Joe had augmented his medical degree from Dartmouth and Harvard with an MPH from Yale. Joe was a Catholic and had a Jesuit education. He had attended a Jesuit high school in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and got his undergrad degree from Holy Cross. His earliest accomplishment was his success in convincing Cardinal Cushing to give support to a law legalizing birth control in Massachusetts. (It is a great story that you should read in the aftermath of the defeat of Roe v. Wade. Dorsey sets an example of how a physician can positively impact an issue of public health importance.)

Under the leadership of Dean Ebert and Joe Dorsey, Harvard Community Health Plan was populated by physicians, nurses, and other healthcare professionals who began their collective journey with a belief in prepaid healthcare that emphasized disease prevention. It was not long until young leaders with an interest in public health like Don Berwick who expanded our collective awareness to embrace the importance of quality and safety wanted to work with Joe. Just how hard it is to introduce new ways of thinking in the practice of medicine is underlined by the fact that even in an organization with a culture of clinical innovation like HCHP there was resistance and pushback to accepting Dr. Berwick’s call to be more focused on the issues public health, population medicine, and the inequities that existed in our system of care and compromised quality and safety.

Many physicians, even in organizations with a mission to create change, find change to be a personal strain and find it difficult in the midst of the work of practice to have the extra energy to move out of the exam room into the wider world of the environmental, social, and policy issues that impacted the health of our patients. It has always been my impression that in the late eighties the management of HCHP became more focused on financial survival and growth than the need to expand our worldview and mission to encompass the broader concerns Don Berwick espoused that became the Triple Aim in 2007. Don left in the early nineties to devote his energy to the Institute For Health Care Improvement.

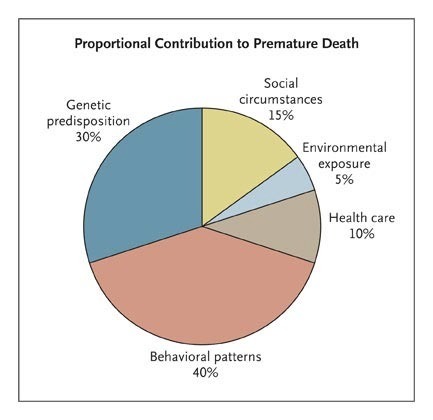

My medical worldview was further expanded toward some of the issues that are emphasized by public health when my colleague, Zeev Neuwirth, exposed me to Steven Schroeder’s September 2007 paper in the New England Journal, “We Can Do Better — Improving the Health of the American People.” If you are a regular reader of these notes, you have seen the important graphic from that paper that dramatically emphasizes that much of what determines the health and longevity of our patients was never studied at the Thorndike Lab.

It is a long road from our traditional view of the origins of disease and what a practicing physician should know and do to the larger view of how the issues of public health, population medicine, and public policy determine the degrees of freedom in the care of the individual and the outcomes of that care.

We think we have come a long way, but the recent overturning of Roe reveals that policy and practice are still intertwined with concepts of personal sin or the sins of others. We now understand that the health of an individual is probably determined as much by where they live and the pollution, or social dangers in their environment as by their genetics. The good doctors at the Thorndike Lab and all of the other wonderful practitioners of the last century did not know that as well as we should know those connections now,

These are times when a controlling conservative minority seems to be turning their backs on all that has been learned over the past fifty or sixty years. The decision last week by the overwhelmingly conservative Supreme Court to gut the ability of the EPA to improve the environment was a substantial reversal considering the threat of global warming and the fact that the Environmental Protection Agency was created in 1970, while I was a fourth-year student, through the efforts of a conservative Republican president, Richard Nixon. According to the link above:

In 1970, in response to the welter of confusing, often ineffective environmental protection laws enacted by states and communities, Pres. Richard Nixon created the EPA to fix national guidelines and to monitor and enforce them. Functions of three federal departments—of the Interior, of Agriculture, and of Health, Education, and Welfare—and of other federal bodies were transferred to the new agency. The EPA was initially charged with the administration of the Clean Air Act (1970), enacted to abate air pollution primarily from industries and motor vehicles; the Federal Environmental Pesticide Control Act (1972); and the Clean Water Act (1972), regulating municipal and industrial wastewater discharges and offering grants for building sewage-treatment facilities. By the mid-1990s the EPA was enforcing 12 major statutes, including laws designed to control uranium mill tailings; ocean dumping; safe drinking water; insecticides, fungicides, and rodenticides; and asbestos hazards in schools.

In time, most of us have accepted the reality that the air pollution from carbon-based fossil fuels also creates global warming and that there is a whole new level of health concerns from global warming for individuals and populations. We have also come to understand that the damaging impact of environmental pollution is greater for disadvantaged populations. We have learned a lot in the last fifty-two years. The court’s decision seems to place the economic interests of fuel-producing states above the health of the nation and especially the health of disadvantaged populations. At a time like this, when we see the destruction of policies and precedents that have been shown to have great public health benefits should medical professionals just shrug their shoulders and go back to the bedside and the exam room?

It is a startling fact that our atmosphere now contains more than 414 parts per million of carbon dioxide. In 1971 when I graduated from a medical school curriculum that was more concerned with disease as an individual concern than as a problem for the whole population, the carbon dioxide level was about 325. Click on the link and check it out:

In fact, the last time atmospheric carbon dioxide amounts were this high was more than 3 million years ago, during the Mid-Pliocene Warm Period, when global surface temperature was 4.5–7.2 degrees Fahrenheit (2.5–4 degrees Celsius) warmer than during the pre-industrial era. Sea level was at least 16 feet higher than it was in 1900 and possibly as much as 82 feet higher.

I wonder why our growth in knowledge has not created a greater sense of the need for collective action and a more organized response from the medical establishment. Is it because we fail to recognize the impact of these issues on the health of the public? Does heathcare imagine that it is better to be quiet until the storm passes? The biggest political and public policy issues before us can be viewed as public health issues. We all agree that COVID and the possibility of other pandemics to come that arises perhaps as a result of the stress on our environment represent a public health issue. Difficulty in obtaining safe abortions will create a whole collection of public health concerns that will impact individuals and families. The existence of AR 15s and other highly lethal weapons and the prevalence of guns of all kinds are public health problems that should be treated as a common threat to the health of individuals. Global warming is a public health problem that will likely move quickly from being a threat to vulnerable individuals to a threat for even our most protected and wealthiest individuals.

We are not slow learners. We have learned a lot over the past fifty years about what threatens our collective health. We learn quickly, but we seem reticent or unable to act. Healthcare has accomplished much in managing disease in the individual. We now need to move those same skills into a greater emphasis on the management of the illnesses of a population.

I have been trying to say in too many words that I have seen a lot of change over the years in medical practice, but it still seems to me that we have not appreciated the unity that exists between the individual and the population. The pandemic, gun violence, and global warming are challenges to the individual and the collective. There is no rational line dividing efforts to improve the care and health of the individual and the care and health of the public. Healthcare professionals could be more effective agents of change, or at least we could be better partners with concerned citizens, politicians, and policy makers. Our hands may seem full with the care of the individual, but unless we more effectively engage in the search for solutions to the challenges to the health of the public our efforts to improve the health of our individual patients will be undermined by the public health problems that we are not effectively addressing.

A Beautiful Evening, Fun on the Green, and the Sense of a Violated Fourth

The picture of the sky at sunset that is today’s header was taken on Saturday evening as we were still enjoying a remarkably beautiful weekend. On Friday evening we enjoyed a “big band” concert on the town green that featured many of the hits of the 30s, 40s, and 50s plus a few hits from the Beatles. Sunday was another big day on the town green. There were games like sack races and “corn hole.” Little children were playing chase while older kids were kicking soccer balls. Adults were tasting delights from food trucks that offered all sorts of summer picnic fare, and a local pub ran a “beer tent” that got a lot of mid-day business. The event was sponsored by a true blue American establishment, The Rotary Club.

Our town doesn’t have a fourth of July parade, but there are plenty of lakes, and people love to shoot off fireworks over lakes and other bodies of water. There were fireworks every evening of the weekend somewhere nearby. I felt sorry for the loons and other wildlife. All of the celebrations seemed out of place by mid-day on the Fourth when the news of the shooting in Highland Park, Illinois arrived. As Pete Seeger’s song says,

Oh, When will you ever learn?

Oh, When will you ever learn?

Enough said,

Be well,

Gene