25 February 2022

Dear Interested Readers,

A Week of Worry and Loss

Like almost everyone in the free world except for Donald Trump and those who for some difficult to understand reason want to live in a nation that he would lead toward some version of fascism, I was deeply distressed to wake up yesterday to discover that Putin had finally invaded Ukraine. It is painful to see a country that has already made great sacrifices to become free subjected to the horror of war because of the unjustifiable ambitions of a despot. In a Guest Essay for the New York Times, Madeline Albright described her impression of Putin when she first met him in 2000.

Whereas Mr. Yeltsin had cajoled, blustered and flattered, Mr. Putin spoke unemotionally and without notes about his determination to resurrect Russia’s economy and quash Chechen rebels. Flying home, I recorded my impressions. “Putin is small and pale,” I wrote, “so cold as to be almost reptilian.” He claimed to understand why the Berlin Wall had to fall but had not expected the whole Soviet Union to collapse. “Putin is embarrassed by what happened to his country and determined to restore its greatness.”

As far as I am concerned, the Russian president has now revealed that he belongs in the very upper echelons of the hall of fame of the most despicable humans who ever walked the earth. I have read that he is motivated to lead Russia back to the status, and territory, that it controlled prior to the end of the cold war. I am afraid that we are on a path that leads to an uncertain destination. I pray for wisdom for our leaders because almost every strategy that they might choose to employ including capitulation to Putin’s crime has significant uncertainty except for the fact that every conceivable next step will cost all Americans some sort of sacrifice.

This may be inappropriate to say, but I fear that Americans born since World War II conceptualize war as something that occurs at a great distance from us and to people who neither look like us nor share much of our cultural heritage. Historically we have preferred not to get involved in international conflicts. “Not our problem” and not worth American lives or treasure have been knee-jerk responses that have been magnified by long and disappointing engagements in Korea, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. To many those places just don’t seem to have much in common with New Hampshire or South Carolina. We care, but we seem to be very careful about acting on our cares in the aftermath of Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam, and Korea. All of our strategies seem to begin with a consideration of what’s best for America at the moment. The problem with that approach is that what is best at the moment in foreign policy is often not what is best over the long term. Unfortunately, we often exercise the same philosophy when approaching healthcare, especially for the underserved who struggle with inequities. “Not my/our problem” is invariably fertile ground for the growth of bigger problems.

To pound my point, sometimes feeling really connected to people who can be categorized as “other” can be hard. “Not our problem” can seem like a very prudent response although history has suggested that “Not our problem” now can be a bigger problem later. I present World War I and World War II as examples. A more recent example might be COVID. We live on a very small planet that is more connected than ever and “Not our problem” is becoming the source of many avoidable tragedies, foreign and domestic.

Sometimes we learn that we are even more connected than we had ever imagined. Every year as St. Patrick’s Day rolled around I used to joke that I was not Irish, but enjoyed the day more since I started living with them. At that time my wife thought that her heritage was 50% Irish, 25% French Canadian, and 25% English by way of Vermont. My attempt at levity on St.Patrick’s Day ended a few years ago when one of our sons called up and said, “Hey Mom, 23 and Me says that I am 25% Ukrainian!” Our response was that there must be some mistake, but there wasn’t. 23 and Me, as well as Ancestry, confirmed that she was 50% Ukrainian and that our other son was also 25% Ukrainian.

My wife has no Irish heritage although all of her sibs do. My wife was the youngest of five, and her four sibs all turned out to be half-sibs. We will be left wishing for answers that we will never find because my wife’s mother, the man she called Dad, whom she will always love as her true father, and the man who was her biological father whom she will never know, have all died. DNA analysis did introduce my wife to many new relatives. She has Ukranian cousins–one that has become a very fun Facebook friend, and possibly a half-sister whom she is unlikely to ever meet. She was fortunate enough to meet the youngest sister of one of the two brothers who are the only men who could be her father. That youngest sister was pretty sure which brother it was.

Through my wife, the family histories of my daughters-in-law, and the mysteries that the application of science can reveal, I feel very connected to the people of Ukraine and Eastern Europe. My wife’s Ukrainian grandparents, she knows exactly who they were, like the grandparents of so many living Americans, came here as immigrants in the great migration of the early twentieth century. Like so many fellow travelers of the time, they were looking for freedom and a better life. They found that better life and have prospered.

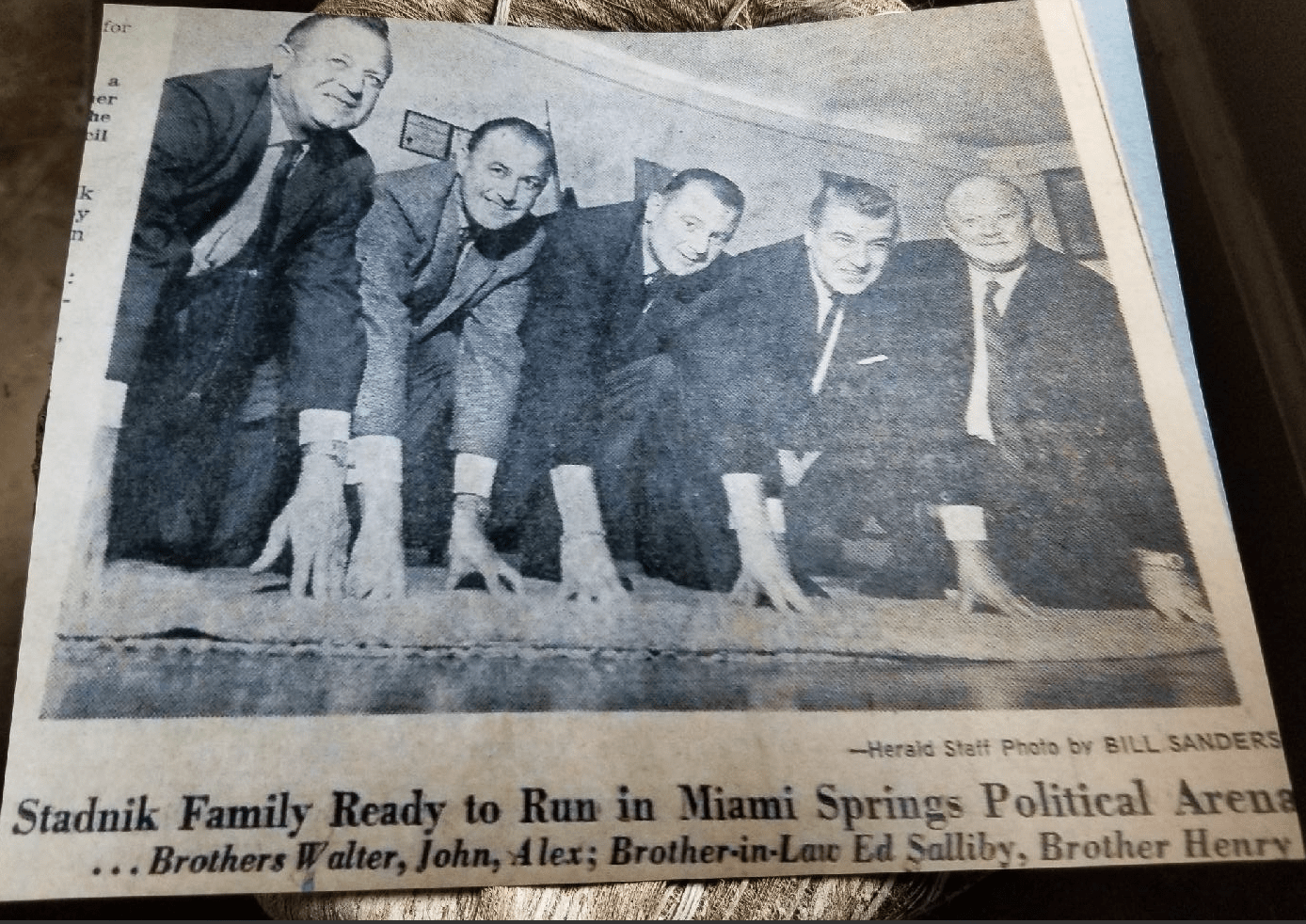

The family, whose name was Stadnik, prospered in Rhode Island and then moved together to Miami Springs sometime in the late forties or early fifties where they had successful businesses and were involved in local politics as the old newspaper picture below reveals. The man on the far left became a local judge, and also got his youngest sister’s vote as my wife’s likely father.

Since the “iron curtain” fell and the USSR disintegrated in the 90s, the relatives that were left behind in the old countries that were behind the “Iron Curtain” have tried hard, none harder or against greater odds than the Ukrainians, to achieve the democratic freedoms that all humans deserve. On the road to freedom, the Ukrainian people have demonstrated great courage and commitment. I am sure that under attack from Russia their struggle will continue. I just can’t believe that we won’t do whatever is necessary to address the crime that Putin committed early on Thursday morning, or that there is any American who could hold him in anything but the greatest contempt. Putin has already demonstrated that he sees the world and the future in ways that don’t make sense to us. He has proven that as long as he is leading a powerful adversary the unthinkable is always possible.

This has been a very difficult week. I had hoped that Putin would see the folly of the adventure he was plotting and that I could devote the entirety of this letter to expressing my grief over the death of two people. One I deeply loved. The other I greatly respected from a distance.

Other than my family, I think the two closest relationships in my life have been with the two women who shared my practice with me. Between 1975 and 1986 my practice partner was Barbara Taylor, NP. Barbara was one of two “founding mothers” of Harvard Community Health Plan. Barbara was ten years my senior and as a VNA had seen a lot and learned more than I would ever know about caring for people who were disadvantaged by the social determinants of health and poverty in general. One of the worst days of my life was when her ovarian cancer presented with a thrombotic CVA while she was seeing a patient in an exam room near me. She was gone in a year, but during that year her greatest hope was to be able to return to her patients.

I doubted that anyone could ever come close to filling Barbara’s place in my professional life, or teach me more, or be a better colleague than Barbara. I learned that someone different with similar but different skills would never replace Barbara but could be as great a pracitce partner in her own unique way. Maxine Stanesa was assigned to be Barbara’s replacement as my partner in 1987. With both Barabara and Maxine I quickly came to realize that they were not there to help me with my practice, but rather we helped each other in our practice. Separations are always difficult. My separation from Barbara was not my choice. She got cancer, had a stroke, and then died way too soon in her early fifties. My separation from Maxine and the practice we shared was the greatest downside of my decision to devote most of my time to administrative responsibilities.

Last Sunday afternoon my wife and I were sitting by the fire enjoying all the taped political talking head shows that are on each Sunday following Jane Pauley’s great “Sunday Morning.” It takes most of the day to get through the newspapers, watch Jane Pauley and then hear those very repetitious and wonky political programs. The routine was broken by my wife’s soft scream, “Maxine has died!” She was reading the Globe on her computer as we watched our programs and, as always, she was reading the obits. There was Maxine. The picture showed the smile that had encouraged so many people to take better care of themselves or had lifted the spirits of so many whose lives had been undermined by the cruel realities of life. The obit did hit the historical events in her life–college activist, early peace core volunteer, honored physician assistant, loving mother and grandmother, and volunteer for the care of the homeless and battered women.

Perhaps, a story can put some perspective on how much Maxine was loved and how patients were willing to wait for her attention. One day, by some quirk of scheduling, compounded by a couple of “no shows,” I saw that there was no one for me to see. At the same time, Maxine was attempting to do the work that would overwhelm at least two people. Feeling like a “goody-goody,” I decided that I would see one of her patients. I picked up a record that was waiting in the box on an exam room door and walked in expecting to be warmly greeted by a grateful patient who was going to get to see the doctor. I was met by a look of disappointment when I announced that I was helping out Maxine. The woman on the exam table looked troubled. After a long pause she sheepishly said, “Dr. Lindsey, I was really hoping to see Maxine.” Equally sheepishly I replied as I backed out of the room, “Right, I understand, I think that she will be with you soon.” I did understand.

Maxine offered something that many clinicians including me never do. She gave every patient her full attention. She treated every concern with the respect that it was due. Many days when most other clinicians were gone, their well-managed work having been completed, Maxine was still in the office seeing someone who had called with an urgent need that could not have been as efficiently managed as Maxine could manage it, had the patient been directed to “Urgent Care,” our “after-hours service.”

On many days when I was headed home exhausted and looking forward to a quiet evening, I knew that Maxine was headed to a clinic for homeless vets to take care of the blisters and other sources of pain in their feet that were so common for people who live on the street. On other days she would be off to volunteer at a homeless shelter where she might help some woman who was trying to escape an abusive relationship. Maxine was a saint, a skilled clinician, and a source of great empathy and wisdom. I never remember her looking away from anyone with a problem. Working with her was a constant source of joy. She was a radiant source of inspiration and enlightenment. She always wore the smile which you can see in the picture below. In the picture, she is surrounded by some of the team who worked in my unit. Maxine is the dark-haired woman in the middle of the picture. As was often true, she is not wearing a lab coat. This picture was taken in March 2008 just a couple of weeks after I assumed the role of Interim CEO. Now fourteen years later, I can’t believe that she is gone and that I never adequately told her how much she meant to me.

After the shock and surprise of learning of Maxine’s death on Sunday, I was already reeling when I learned on Monday that Paul Farmer, the Albert Schwitzer of our times, had died in his sleep of a cardiac event at the age of only 62. All of the obituaries that I read were inadequate attempts to put his life into perspective. If you didn’t read Tracy Kidder’s 2003 book about Dr. Farmer’s work, Mountains Beyond Mountains, let me offer you a couple of paragraphs from the New York Times review of the book which is as much a quick picture of Farmer’s essence as it is a review of Kidder’s magnificent writing:

”The world is full of miserable places,” Tracy Kidder writes. ”One way of living comfortably is not to think about them or, when you do, to send money.” ”Mountains Beyond Mountains” is about one physician’s quest to relieve suffering in just the kind of places we do not like to think about. In a stylistic departure from most of Kidder’s previous books, he writes in the first person, offering himself as a character and even as a foil, so that his own reactions of admiration, skepticism, exasperation and awe provide a second lens by which to see Dr. Paul Farmer.

A latter-day Schweitzer, Paul Farmer divides his time between the Harvard medical complex — a ”Wall Street of medicine,” as Kidder describes it — and Haiti. ”Out there in the little village of Cange . . . in one of the most impoverished, diseased, eroded and famished regions of Haiti, there was this lovely walled citadel, Zanmi Lasante. I wouldn’t have thought it much less improbable if I’d been told it had been brought by spaceship.” The Zanmi Lasante hospital serves about a million people and represents years of single-minded effort by Paul Farmer.

I only knew Dr. Farmer from a distance. I would like to think that I might have been his attending when he was a house officer at the Brigham in the eighties. He was a most remarkable doctor who had made more real contributions to humanity before he finished his medical training than most doctors make in a lifetime. As I tried to remember my own distant experience with Dr. Farmer, I found an old interview that was reprinted in the Harvard Gazette, and then quite by accident I heard Atul Gawande’s reflection on Farmer’s good humor on NPR. These two sources were more beneficial in “knowing” Dr. Farmer than all the news reports and obituaries that have appeared in the wake of his death. I hope that you will treat yourself to both.

You may remember that a couple of weeks ago I wrote once again about the African theological concept of Ubuntu, “I am because we are.” Dr. Farmer was a believer in the power of Ubuntu and besides being the author of more than ten books describing his philosophy, his experiences, and creating a framework for the concept of “global health,” he also appeared in a 2008 documentary with Madonna entitled, “I Am Because We Are.” Perhaps the best way to sum up Dr. Farmer’s life is to say that the spirit of community was a driving force behind his work, and his work was most remarkable in that he had the world’s most expansive concept of community.

A week when we have a diabolical maniac attack all concepts of community and lose two souls whose lives were beautiful examples of how magnificent a gift a life lived for a community can be, is a week that should make us all stop and reflect on what we want to do in this world. Over the last sixty years, I have not spent a lot of time praying. I am not good at it despite the fact that I grew up in a home where the word prayer was one of the most frequent words heard, and the act of communal prayer was more frequent than meals. These days I find myself trying to rediscover how to pray. During a week like this last week, prayer seems like a necessary strategy. I see the wisdom in the suggestion that we should pray as everything depends on God’s grace, and work as everything depends on us. The question is what work should we do. I think building community is work that creates equality and improves health most directly, and every one of us has the ability to carry the spirit of Maxine Stenesa and Paul Farmer into the communities where we live. Pushing forward with a sense of community that spans the world is the only attitude that is powerful enough to overcome the evil of Putin and the self-serving ambitions of some of those among us who think he is a genius.

New Snow Is Falling In Maple Syrup Time

As I finish this note to you we are halfway to the prediction of a fresh foot of snow. The weatherman says that it will continue to snow all afternoon. It’s hard to believe that a little more than 48 hours earlier the temp was in the mid-sixties and our snow was melting fast. The oscillation of warm and cold is what makes the sap in maple trees rise.

Today’s header shows my friend Steve’s “sugar shack.” We got a text earlier today saying that he was “boiling” today and that we should drop by. A subsequent text said, Don’t bother. The sap in the holding vat is frozen. That is OK because any travel is unlikely until after the roads are plowed. Over the last several years I have watched Steve’s curiosity about making maple syrup become an avocation which has now grown to a major focus for his late winter social life.

It was not long ago that he would sit in the open field behind his house and boil the sweet sap into a syrup as friends gathered around the fire sitting on lawn chairs. Sitting there in the cold with wet feet we would drink a beer or sip on wine while telling stories and jokes, discussing local politics, or asking each other how in the world Donald Trump got elected president and what that event might mean about the future of the human race. It was different and interesting, but very uncomfortable. One attended the gathering to support Steve in his effort and to seek to “enjoy” the slow ending of winter which the flowing sap suggested would come in a few weeks.

There must be something addictive about making maple syrup because with each passing year Steve’s operation has expanded. He started out in the traditional fashion by tapping “taps” into the maple trees that surrounded his property. Then he would hang a bucket from the tap to catch the precious fluid as it dripped out. He would then carry the buckets to the pan that was resting over the open fire and pour in the sap as we all watched and looked for opportunities to help. That is old school. These days the “industrial” producers use taps with complex internal valves and the trees are networked with miles of plastic tubing that flow into huge central containers. The woods are full of these tubes that form a spiderweb-like network that unites the trees.

After the network of tubes has dumped the product of all the taps into a big plastic tank at the edge of the woods, another tube attached to a pump is used to draw the precious fluid from the collection tank into a stainless steel holding tank on the outside wall of the “sugar shack.” Look at the picture closely and you can see the blue tubing running up to the stainless steel tank on the side of the building. Steve can be nice and warm in the steamy shack as the sap flows from tree to boiler through valves, tubing, and tank with the aid of a little pump. The system is engineered for efficiency.

It is a remarkably engineered system that allows the sap to be drawn into the vat inside the steamy “shack” where we and other friends gather to sit comfortably in rocking chairs while we enjoy our libations, swap our stories, watch Steve and his wife Nancy turn valves, and feed the fire with precisely chopped logs. It’s almost like the syrup makes itself. As an added bonus, the steam coming off the vat keeps the air moist and the room warm.

Inside the shack, there is more to do than my analysis might lead you to imagine before that amber sweetness ends up in a jug. The specific gravity of the boiling fluid is monitored. There is filtering, and then there is the final boil that produces the finished product that is then carefully poured into a plastic jug like the ones you may see in the grocery store.

It takes fifty gallons of sap, a lot of firewood, and hours of focus to make a gallon of syrup. When you figure in the transportation costs and all the labor it’s hard for me to understand how maple syrup is sold for less than a thousand dollars a pint. The economics are not my problem because we get most of our syrup from Steve and Nancy for free! I love the syrup, and I have found that you can pour it on anything you eat and put it in some of the things you drink. There are even local microbreweries that produce a flavorful stout with maple syrup. That’s a winning combination!

If you want to get into some of the fun, March is Maple Sugar month in New Hampshire. It’s our own special kind of “March Madness.” You can click here to check out the events that are offered. As described below, the weekend of March 19-20 is the grand finale.

New Hampshire Maple Month is coming: find the Sweet spot near you!

Give cabin fever the boot in March: get out for Maple Month in New Hampshire! Support your local sugarhouses to help support the sugaring tradition all month but especially during Maple Weekend, March 19 and 20. Click here to find one near you.

Sugarhouses will have their own COVID protocols for visiting and/or buying during the pandemic so check their listings or call ahead for details about online ordering, Maple to Go, appointments to visit, and more.

My wife and I usually visit several local sugaring operations that special weekend to taste their products for free and stock up on a supply to augment what Steve gives us because we always give some maple syrup to friends when they visit through the year. In New Hampshire, there are two items, firewood, and maple syrup, of which you should never allow your personal supply to run low.

As I finish up this note to you, watching the snow accumulating again, I know that I will have much work to do tomorrow. Winter isn’t over yet, but spring is coming soon as the sap is rising. Mud season is just ahead!

Be well,

Gene