April 14, 2023

Dear Interested Readers,

Examining The Political Determinants of Health

Last fall, an Interested Reader who lives in Florida sent me an article by Dr. Eric Reinhardt entitled “Medicine for the People: As more and more doctors awaken to the political determinants of health, the U.S. medical profession needs a deeper vision for the ethical meanings of care.” I was intrigued by the article and wrote about it in my December 9th letter to you. I was even more intrigued by the fact that as much as I have emphasized healthcare disparities, health equity, and the social determinants of health I had not yet come across the term “the political determinants of health.” It seemed like such an obvious and important concept that I was surprised that I had never heard of it or thought of it.

We have measured the inequities, identified the components of our healthcare problems, and theorized about care delivery and finance changes that might improve the social determinants of health and reduce healthcare disparities, but we have not placed much emphasis on the political and policy history that produced the inequities and the potential policy changes that might lead to better outcomes. It seems that we have been focused on using the shame of our deficient outcomes, and the immorality of the inequities in our system of care to motivate the changes we desired. We need to look no further than the international shame we should feel over gun violence in America to know that shame doesn’t motivate change in an activity that generates as much revenue in its current state as healthcare does. Collectively, we seem incapable of “doing the right thing” when doing the right thing might have transitional costs or harm the keepers of the status quo. Our reluctance to give up slavery 150 years ago is a perfect example of how we are perfectly capable of tolerating inequity and gross injustices as long as they are not an obvious economic problem for the majority.

There is a historical political policy explanation for every one of our healthcare concerns and vulnerabilities. Making meaningful change will require political policies and not just data that shows that a minority of millions are underserved and injured by the social determinants of health. We should know from our struggle with guns and abortion, two issues where at least sixty percent of voters say that they want change, that because of how our system of government functions a well-organized and well-funded minority can maintain control and prevent change. It seems that if progressive ideas are going to be given a chance we will need either a very large Democratic supermajority in Congress or some unlikely spiritual revival that precipitates a reversal of our current deep political divisions. What is even more flabbergasting is that the preservation of the status quo is not even in the best interest of a majority that can be conned into believing that change should be resisted for cultural reasons or for the fear of losing control to some combination of those they consider to be “other.”

There is a growing literature about the historical and foundational importance of the political determinants of health. We are becoming more aware of the reality that things are the way they are because of past political policies and court decisions. Things will not be different in a positive way without future political policies that guide change toward equity. Those changes won’t occur without effective political advocacy for healthcare equity. Becoming more acquainted with the concepts of the political determinant of health will enable the implementation of more effective strategies. Those strategies can be distilled down to electing those who will govern and create policies in ways that correct the existing disadvantages in housing, education, transportation, employment, availability of good nutrition, the abolition of institutional biases which diminish health, and policies that promote the public investment in the positive changes that will move us toward a more equitable and healthy future.

An understanding of the political determinants of health leads us to understand that the role of advocacy is not over after sympathetic politicians are elected. The system also has power through the courts, through regulators, and through the pressure of vested interests on elected officials to prevent or delay the completion of potentially positive change. We saw it all in the run-up and after-experience of the ACA. Another good example of how the system resists change for as long as possible is the fact that in 1954 in Brown v. The Board of Education, The Supreme Court ruled that separate but equal educational systems were unconstitutional, but the court’s decision in some Southern states was effectively avoided until the 70s.

Ironically, contrary to resistance, it is not hard to recognize that in the long run changes that would hasten health equity and improve the social determinants of health would improve the personal health and economic well-being of everyone–even those who think they are fine now. More importantly, without those changes, things will inevitably deteriorate. We need to look no further than the resistance to preventing global warming and the increasingly violent weather we experience to see that the road we are on leads to someplace none of us wants to go.

Understanding the political determinants of health and using that knowledge to overcome the power of the status quo is critical if we are ever going to improve the social determinants of health and improve the health of the nation. A review of our national history reveals that moral and practical arguments alone have rarely led to improvement, but coupling moral and practical considerations with advocacy, focused political power, and progressive policies have irradicated slavery, eliminated most child labor, improved the position of women in society, created a barely adequate social security system, and until recently through the ACA given as many as 92% of Americans access to healthcare. Progress has been made in every area of the social determinants of health, but there is much more that needs to be done. What needs to be done won’t happen until we effectively deploy the strategies that are associated with the political determinants of health.

What I have quickly learned is that one of the principal proponents of the concept of political determinants of health is Daniel Dawes who is the director of the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at Morehouse School of Medicine. He published The Political Determinants of Health in 2020. The forward was written by David Williams who is the Florence Sprague Norman and Laura Smart Norma Professor of Public Health and Chair of the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Professor of African and African American Studies and Sociology at Harvard University. In his forward, Dr. Williams writes:

“…we are not the healthiest people, even though we certainly should be, given our yearly per capita expenditure on health care—more, per person and absolutely, than in any other developed country. According to the World Bank, half the annual expenditures worldwide on medical care are spent in the United States. We represent fewer than 5 percent of the world’s population, consume one half of its medical resources, yet we still rank near the bottom of industrialized countries for health. Why are we receiving such a poor rate of return? More importantly, why are we comfortable with these outcomes? Published research has exhaustively answered the first question. More tellingly, an answer to the second question can be found in academic journals. But, by reframing the context of the problem, Daniel Dawes has succinctly answered both questions: one needs to look no further than the political determinants of health.” [bolding added by me for emphasis]

In his first chapter, Dawes writes:

As a society, we have been conditioned to believe that equality, which is giving everyone the same treatment, is the solution for all. When, in fact, equity, which is rooted in the principle of distributive justice or “concern with the apportionment of privileges, duties, and goods in consonance with the merits of the individual and in the best interest of society,” is what society should be striving for.

Opportunities equally distributed do not address the individual needs and circumstances of a community.

The notion of equality fails to appreciate the multidimensional systemic issues involving economic, social, cultural, historical, and political factors that unfairly advantage some groups and disadvantage others…

Dawes points out that if our goal is improvement then equity can only be achieved by recognizing the policy decisions and barriers of the past that have resulted in the current inequities. The most obvious errors of the past include the destructive treatment of indigenous people, African Americans, and all minorities. The perpetuation of discrimination against these “out-groups” plus others like the LGBTQ+ community, the mentally ill, the disabled, and the poor from all groups has been augmented by public policy, executive decisions, and court rulings. Dawes painstakingly reviews the long history of legislative, judicial, presidential, and administrative decisions that have created the challenges that have created the circumstances that we call the social determinants of health.

Those individuals and groups that lack equity will need policies that grant them restorative benefits that create equity. I am reminded of the educational policies that exist in some states that require and demand that every child be educated to their full potential even if it requires special resources. To correct the damage of previous discriminatory policies we will need new policies that are directed toward correcting those existing inequities. Those solutions will require improved political determinants of health. There have been some partial victories. The ACA was a huge attempt to politically improve the social determinants of health. Dawes also teaches us that no victory is secure. He was writing before the Supreme Court’s reversal of Roe, but there are other examples in history. Recently we have seen childhood poverty reduced by the child tax credit. We have seen millions acquire healthcare through policies associated with COVID. Now the tax credit that was so beneficial is gone, and millions are discovering that they are no longer eligible for Medicaid. In 1980, President Carter signed landmark legislation that advanced community-based mental health. Reagan defunded it within six months of becoming president. The way in which our government frequently changes with elections allows progress under one administration to be reversed by the next administration controlled by the other party is a political determinant of health.

If we are ever going to achieve health equity and give every American the health we need them to have. we will need to move beyond measuring inequities, describing the social determinants of health, and complaining about the cost of care and bad outcomes. We will need to pass laws and develop policies that correct many of the bad policies of the last two hundred and forty years that have created the current situation, and then defend those decisions and policies. There is a lot of political work between where we are and equality in healthcare. It seems that no accomplishment is guaranteed to be permanent.

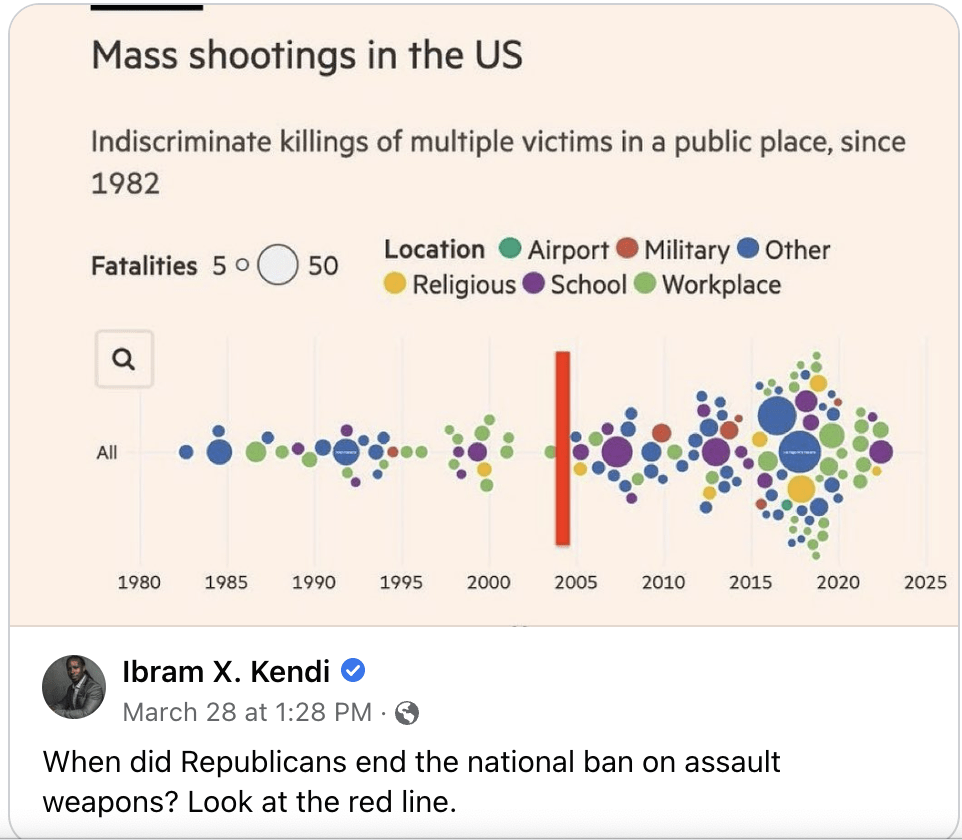

Under a broad definition of healthcare disparities is gun violence. In this country guns kill tens of thousands of people, many of them children, every year. Guns are now the number one cause of death in children and teens. An example of how progressive legislation can be replaced by regressive resistance, the fate of the 1994 ban on assault rifles is a good example. Less than a month ago, Ibram X. Kendi published an interesting graphic on social media that shows the increase in mass shootings after the ban failed to be renewed in 2005.

Over the last two weeks, we have suffered mass shootings in Nashville and Louisville. We have seen the dramatic fallout in the Tennessee House of Representatives which was a manifestation of how difficult it is to pass legislation that a majority of Americans say they support, but that is opposed by a powerful, well-funded, minority. Is it any wonder that our attempts to improve the social determinants of health seem like such a slow uphill grind?

Consider this note to be an introduction. I will continue the discussion of political determinants of health in the weeks and months to come.

Spring Is Here. The Ice Is Almost Out.

I usually start fishing in Little Lake Sunapee by mid-April. It will be a little later this year because up till now there has been a lot of ice on the lake. The good news is that it’s been warm this week. It was 80 yesterday, so I expect that I will be on the water next week. It has been a strange winter with many days warmer than usual, but the lake has been frozen since mid-December, and we have had a constant snow cover since then. There is still snow in the shaded areas of my yard. It amazes me that in some areas of our yard, it is still over a foot deep when the temperature is 80! This morning there was still some ice on the lake.

This was a busy winter for wood delivery for our nonprofit organization, Kearsarge Neighborhood Partners. With the stress of inflation and the high cost of fuel, many people in our area were heating with wood. The usual routine is to have a heating system that is fueled by propane or heating oil plus a wood stove. A few people heat with electricity. Many families use wood to diminish their dependence on oil or propane. The heating problems this year were compounded by the fact that wood was also more expensive. Seasoned wood sold for $350 to $450 dollars a cord.

Most low-income families take advantage of fuel allotments of up to $3000 from the government. In fact, this benefit should improve the social determinants of health. The process of getting federal assistance for fuel is much like food stamps, now called SNAP, the acronym for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. The amount you receive is a function of income, family size, and the size of your home. This year, the process of determining eligibility and paying suppliers was delayed and hampered by workforce shortages in the Community Action Partnerships of New Hampshire which are contracted to deliver federal funds. Suffice it to say, with inflation and the delays there were many more New Hampshire residents who had heating difficulties this winter than in years past even though we had a relatively mild winter.

Our nonprofit supplies wood for people who have emergency needs for heat. We also purchased a couple of dozen safe electric heaters for emergency use. We buy green wood in the spring and summer when it sells for about $200 a cord and accept wood donations from people in the community who might be taking down trees. Recently, we were given a grant that allowed us to buy an excellent wood splitter and a large trailer. On typical deliveries, we usually use the trailer plus one or two pickup trucks to deliver up to a cord of wood. Some of our “regulars” who can come to our wood lot just take wood as they need it and call my wife who manages the program and tell her how much they took so that she can manage the inventory. For emergencies, we leave wood for the taking at two places where people come for free food. One is a local food bank, and the other is a community store (you should click on the link) that has an outdoor shelf where there is food that is “free for the taking.”

Because we knew that this would be a difficult year, the board of KNP earmarked $36,000 dollars this winter for emergency purchases of oil, propane, and electricity. Fortunately, we did not need to spend nearly that much money, but we did deliver a lot of wood. At times I was concerned that we would run out of wood before the heating season was over. That did not happen as the picture below shows, we have about three or four cords left on our wood lot.

I think we made it because there were several people who allowed us to pick up their wood and deliver it to those in need. It is good exercise!

Today’s header shows about three cords of “bucked wood” that we picked up on Monday donated by the owner of a very handsome estate with gorgeous hilltop views between Mount Kearsarge and Ragged Mountain. “Bucked wood” describes logs that are cut in 18 to 24-inch lengths with a chain saw. Those shorter logs are ready for splitting. In a few weeks, we will have a “splitting and stacking party” to process this wood for seasoning and delivery next year.

All around town, I see that the spring cleanup is in full swing. In a few weeks, we have a town cleanup where citizens all work together to sweep away what is left from winter. Working in the warm spring sun with friends is good fun and good exercise. I hope that you have plans to take advantage of any good weather coming your way this weekend.

Be well,

Gene