Last year I was delighted to write a preface for the book on patient and family centered practice written by Anthony DiGioia and Eve Shapiro, The Patient Centered Value System: Transforming Healthcare through Co-Design. Recently Eve emailed me with the request that I help her find some healthcare professionals, “doctors, nurses, and others” from the front lines of patient care who would be willing to be interviewed for thirty or forty minutes on the telephone. She has a contract with a medical publisher for a book that will “focus on what providers say they need in order to experience joy and meaning in work–specifically under what circumstances they have experienced it (or not), what promotes or inhibits it, and what people say they need in order to realize it.” She would also like to talk to some healthcare CEO’s and medical managers so that she can “understand the connection, or disconnection between the perspectives of front line providers, CEOs, and other medical managers.” Her email is eveshapiro912@gmail.com. You should contact her because nothing helps you understand your own view of the world like the opportunity to explain it to someone who really wants to know how you see the world and yourself in it.

As I was thinking about Eve’s request I said to myself, “I need to write about my perspective on what Eve wants to know!” In retirement I have not forgotten the full range of the experience of practice from unsurpassed joy to occasional utter frustration and a sense of victimization by a system gone off the tracks. I spend a lot of time thinking about all the ups and downs of almost fifty years of training and practice. I also know the joy and frustration of having the responsibility to make the experience of practice better for those those working in the delivery system, as well as the experience of trying to work through others to improve the experience of care for our patients.

The experience of “joy” is very personal, as is the flip side of joy however you may define it, be it frustration, world weariness, tedium, disappointment, or outright anhedonia. If we are to describe how we personally experience joy we need a little bit of personal history.

It is said that if one is in the right work for them it never really feels like work. That was my experience in practice.

My parents modeled a life of responsibility and service. Money was never a motivator for them and as a result a secondary concern for me. My parents believed that we all have “a calling” and that we individually have the responsibility to discover the nature of that call. They came at everything from the context of Divine direction.

As I tried to rationalize their world view, my own interests, and the science that I eventually learned, it was not a big leap from their sense of “a calling” to an amalgam of natural talents (genetic gifts), nurtured interests, culture, and experience. They created an environment that encouraged exploration and conversations about the experiences along the way. I never took a job because of the high pay it might offer, although I took a lot of jobs because I had financial obligations. Again, their stated philosophy was always “God will provide what you need” although their belief was based in the expectation that most of what God provided was the energy and intelligence to take care of yourself.

Considering my family of origin, I was destined to be in some kind of “service.” I could be a minister, doctor, social worker, or a teacher, and my choice would match their expectations of me. Other choices would have been fine, as long as I could define my choice in the context of the service the work provided to others.

As a high school senior, I was hospitalized for a work up of hypertension when I presented with a severe sore throat, and a systolic BP north of 180. My PCP called in one of the most respected cardiologists in our community, Dr. Masters, who was also my Sunday School teacher. Dr. Masters was an old school doctor who had trained at Vanderbilt. He had that frumpy, empathetic professional appearance that Norman Rockwell captured in his painting “The Doctor and the Doll.” My PCP and Dr. Masters took an interest in me, and through them I saw myself as a doctor. I reasoned that I was good in science and I liked the idea of serving people, so perhaps being a doctor was my “calling.”

My father was not so sure. He suggested that I get a job at the local hospital working as an orderly. I loved the work. I liked walking patients, giving baths, and assisting nurses with dressing changes. I “mastered” making a “tight bed.” I got plenty of exercise rolling around oxygen tanks and pushing patients from the emergency room to the floor, or from the floor to x ray. My most profound experience was helping take care of burned patients and a patient on the surgical floor who had multiple fistulas. Leaving for medical school (with a recommendation written by Dr. Masters) I thought I was headed to the life of a surgeon.

I had a ball in medical school. The “preclinical” years were made less onerous by frequent opportunities to tag along on rounds with attendings or go to special “clinics” on Saturday mornings where patients were presented to provide context to our classroom and lab work. Once the clinical years began I was always eager to “be” some day what I was seeing on each rotation. On OB I imagined a life of delivering thousands of babies. Rounding with Dr. T. Berry Brazelton on my pediatric rotation made me a pediatrician for sure. I was certain that I wanted to be a psychiatrist after a rotation at Mclean Hospital. Surgery was interesting, but not quite what I thought it would be. There was a lot of attention to hierarchy that did not appeal to me.

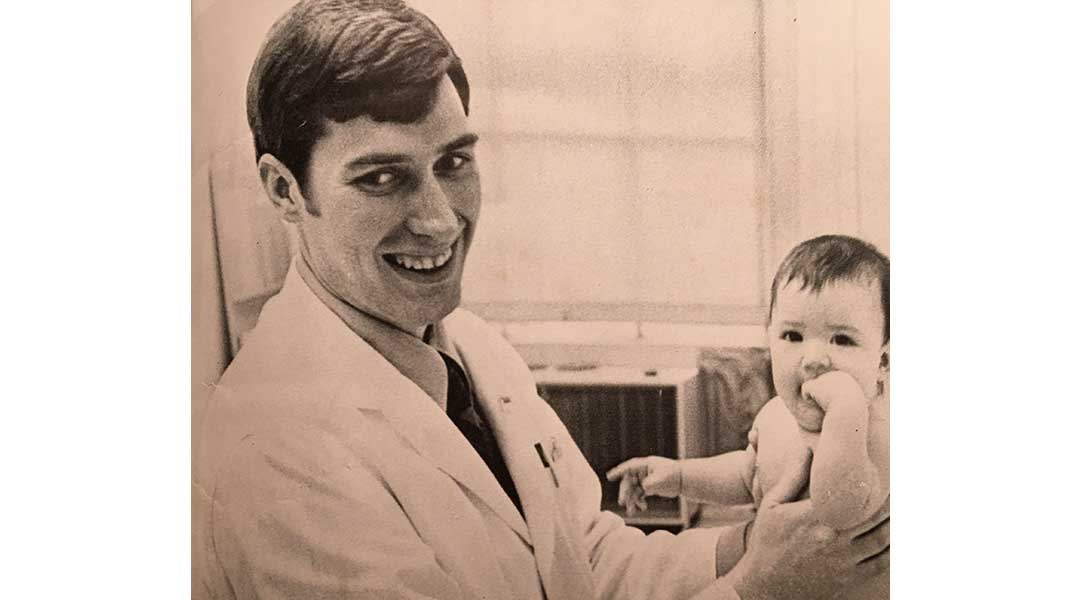

I found myself realizing that the joy for me was in the interaction with patients and families. I became involved in the family medicine practice at Children’s Hospital and for two years joyfully served as the PCP for three families. The picture with this post shows a much younger me with one of my patients. After considering family practice, I took the standard path of a medical internship at the Brigham where I had done my medical school medicine rotation. The Brigham was a good fit for me and when I decided that I would be a better PCP if I had training in a medical subspecialty, I stayed on for a cardiology fellowship.

The greatest serendipity I have ever experienced was to become a student at Harvard Medical School while our dean, Dr. Robert Ebert, was creating Harvard Community Health Plan. At the Brigham I met Dr. Marshall Wolf who was the first cardiologist at HCHP and was doing just what I wanted to do. In 1975 he was offered the job as house staff director at the Brigham, and then he convinced me that I should take his practice at HCHP.

HCHP was a learning lab populated by like minded souls, all committed to the concepts that would morph years later into the expression of the Triple Aim. The road forward was never easy because the status quo and the external world were always pushing back, but the satisfaction of the practice was always enough to allow me to tolerate the internal manifestations of the external world.

Over the last forty years the practice of medicine has been bombarded by external challenges. Our growing knowledge and expertise has not been associated with a wisdom that has made the benefits available to everyone at a sustainable cost, and in an environment that supported professional growth, satisfaction, and joy. Running harder and faster has allowed many physicians to marginally maintain their income, but they have become fatigued and disheartened as they labored in environments that were not supportive in the way I found HCHP and its legacy practices to be.

I do not think job satisfaction is a function of compensation, nor do I think joy in work is the same as job satisfaction. Compensation issues can be a huge source of job dissatisfaction and has the ability to kill any joy a job can generate. Several years ago I read Daniel Pink’s thoughts on motivation, compensation, and job satisfaction in his 2009 book, Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. Pink asserts that most professionals value autonomy, mastery and purpose, and are more motivated by the heuristic satisfaction, the opportunity to solve problems, than by the absolute numbers on their paycheck.

Pink points out that although the business world has depended on external “carrots and sticks” for motivation that the greatest progress and our greatest satisfactions arise from the successful expression of “intrinsic” desires. Intrinsically, I love solving problems and helping people. My greatest satisfactions and moments of joy in practice came when I made a positive difference in someone’s life or helped solve a problem as a manager that made the system better for everyone. That joy was greatly multiplied when my efforts were harmonized with the efforts of colleagues, and we functioned as a “winning” team for our patients and our practice.

I am saddened when I think that the joy of practice has been diminished by our growing focus on finance and its dependence on RVU based calculations of compensation. The need to document every erg of effort has created an unacceptable environment. I will not be the first to emphasize that caring for patients is not the same as generating a bill that will be paid by a third party. When I think about how colleagues have struggled with electronic medical records I am saddened.

The heuristic joy of autonomous problem solving seems in conflict with the algorithmic processes that have evolved as we seek to meet quality objectives, but it does not need to be so. Algorithms and quality metrics can guide us to improvement and better engineering of the delivery system could free up the valuable time we need to consider the unique concerns of patients. Perhaps with better engineering of the care process we could create more time to give to patients. Increased time for clinician/patient interactions could increase the joy of practice for clinicians and increase the satisfaction of patients.

Even though the joy in practice may vary from individual to individual based on their own personal history and preferences, I believe in the possibilities of better care and a better work experience if we take advantage of our growing knowledge of systems, and our expanding capabilities in continuous improvement. I also believe that it is always important for us to examine how our own choices can diminish our joy. That is why we must ask, “What part of the problem am I/ are we.” It is my hope that our growing understanding of what motivates and demotivates us coupled with better systems through continuous improvement and rededication to putting the concerns and needs of patients and families first will move us back toward the joy in practice that so many say that they have lost.

The Triple Aim and joy in practice are not ideas in conflict, but rather they are mutually reinforcing concepts and the best way forward. We are deep into collective efforts for mastery of quality. We can have the autonomy to solve problems in practice as individuals and as teams. We can have it all, if we realized that the challenge is for all to have it. It is my belief that if we keep our eyes on that prize, and the justice it entails, we will all have more joy from our efforts and find the energy and strength to solve the problems that frustrate and fatigue us now.